How Litigation Spurred Auto Safety Innovations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automotive Maintenance Data Base for Model Years 1976-1979

. HE I 8.5 . A3 4 . D0T-TSC-NHTSA-80-26 DOT -HS -805 565 no DOT- TSC- NHTSA 80-3.6 ot . 1 I— AUTOMOTIVE MAINTENANCE DATA BASE FOR MODEL YEARS 1976-1979 PART I James A. Milne Harry C. Eissler Charles R. Cantwell CHILTON COMPANY RADNOR, PA 19079 DECEMBER 1980 FINAL REPORT DOCUMENT IS AVAILABLE TO THE PUBLIC THROUGH THE NATIONAL TECHNICAL INFORMATION SERVICE, SPRINGFIELD, VIRGINIA 22161 Prepared For: U. S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Research and Special Programs Administration Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, MA 02142 . NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Govern- ment assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse pro- ducts or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturer's names appear herein solely because they are con- sidered essential to the object of this report. NOTICE The views and conclusions contained in the document are those of the author(s) and should not be inter- preted as necessarily representing the official policies or opinions, either expressed or implied, of the Department of Transportation. Technical Report Documentation Page 1* Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. _ DOT-HS-805 565 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Dote Automotive Maintenance Data Base for Model Years December 1980 1976-1979 6. Performing Orgonization Code Part I 8. Performing Organization Report No. 7. Author's) J ame s A Milne , Harry C. Eissler v\ DOT-TSC-NHTSA-80-26 Charles R. Cantwell 9. -

Downfall of Ford in the 70'S

Downfall of Ford in the 70’s Interviewer: Alex Casasola Interviewee: Vincent Sheehy Instructor: Alex Haight Date: February 13, 2013 Table of Contents Interviewee Release Form 3 Interviewer Release Form 4 Statement of Purpose 5 Biography 6 Historical Contextualization 7 Interview Transcription 15 Interview Analysis 35 Appendix 39 Works Consulted 41 Statement of Purpose The purpose of this project was to divulge into the topic of Ford Motor Company and the issues that it faced in the 1970’s through Oral History. Its purpose was to dig deeper into that facts as to why Ford was doing poorly during the 1970’s and not in others times through the use of historical resources and through an interview of someone who experienced these events. Biography Vincent Sheehy was born in Washington DC in 1928. Throughout his life he has lived in the Washington DC and today he resides in Virginia. After graduating from Gonzaga High School he went to Catholic University for college and got a BA in psychology. His father offered him a job into the car business, which was the best offer available to him at the time. He started out a grease rack mechanic and did every job in the store at the Ford on Georgia Ave in the 50’s. He worked as a mechanic in the parts department and became a owner until he handed down the dealership to his kids. He got married to his wife in 1954 and currently has 5 kids. He is interested in golf, skiing and music. When he was younger he participated in the Board of Washington Opera. -

In Re Ford Motor Company Securities Litigation 00-CV-74233

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION Master C e No. 00-74233 In re FORD MOTOR CO. CLASS A TION SECURITIES LITIGATION The Honorable Avern Cohn DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL CONSOLIDATED COMPLAINT FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 l r" CJ'^ zti ^ OVERVIEW 1. This is an action on behalf of all purchasers of the common stock of Ford Motor Company, Inc. ("Ford") between March 31, 1998 and August 31, 2000 (the "Class Period"). This action arises out of the conduct of Ford to conceal from the investment community defects in Ford's Explorer sport-utility vehicles equipped with steel-belted radial ATX tires manufactured by Bridgestone Corp.'s U.S. subsidiary, Bridgestone/Firestone, Inc. ("Bridgestone/Firestone"). The Explorer is Ford's most important product and its largest selling vehicle, which has accounted for 25% of Ford's profits during the 1990s. Due to the success of the Explorer, Ford became Bridgestone/ Firestone's largest customer and sales of ATX tires have been the largest source of revenues and profits for Bridgestone/Firestone during the 1990s. During the Class Period, Ford and Bridgestone had knowledge ofthousands ofclaims for and complaints concerning ATX tire failures, especially ATX tires manufactured at Bridgestone/Firestone's Decatur, Illinois plant during and after a bitter 1994-1996 strike, due to design and manufacturing defects in, and under-inflation of, the tires, which, when combined with the unreasonably dangerous and unstable nature of the Explorer, resulted in over 2,200 rollover accidents, 400 serious injuries and 174 fatalities by 2000. -

Ci Council Agenda Item Meeting of May 5, 2020

Ci Council Agenda Item Meeting of May 5, 2020 TO: The Honorable Mayor and Members of the City Council FROM: Monte K. Falls, P.E. - City Manager {V\~l,.bO ,i.,.;:;., 1' f;t-t(~~ DATE: April 23, 2020 SUBJECT: Water and Sewer Department Service Truck Replacements - $75,000.00 REQUESTED BY: City Manager/Water and Sewer Director The following is requested as it relates to the above-referenced agenda item: X Request Council review and approval based on the attached supporting documentation. No action required. (Information only) DEPARTMENTAL CORRESPONDENCE WATER AND SEWER DEPARTMENT To: Monte K. Falls, P.E., City Manager From: Robert J. Bolton, P.E., Director "- Date: April 15, 2020 RE: Service Truck Replacements, $75,000.00 Recommendation: !II Place this item on the City Council's Agenda for May 5, 2020; • Approve purchase of two (2) service trucks to replace existing service trucks in the Lift Station Division that was not budgeted in FY 19/20. This request is for approval in amount not-to-exceed $75,000.00. Funding: Costs will be charged to fund 423.9010.536.616050. A line item budget transfer has been prepared to transfer funds from account 423.9010.536.673161 (Gravity Sewer Rehabilitation). Background: The Water and Sewer Department has two trucks Nos. 9804 and 9805 that are in disrepair and need to be replaced. No. 9804 is a 2006 truck with a bad engine. No. 9805 is a 2008 truck with a rusted out body. Both of these trucks are in the lift Station Division and are used to lift pumps out of the lift stations for repair via a crane that is mounted to the truck body. -

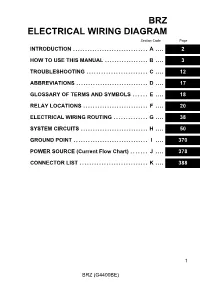

BRZ ELECTRICAL WIRING DIAGRAM Section Code Page INTRODUCTION

BRZ ELECTRICAL WIRING DIAGRAM Section Code Page INTRODUCTION............................... A .... 2 HOW TO USE THIS MANUAL.................. B .... 3 TROUBLESHOOTING ......................... C .... 12 ABBREVIATIONS . D .... 17 GLOSSARY OF TERMS AND SYMBOLS...... E .... 18 RELAY LOCATIONS........................... F .... 20 ELECTRICAL WIRING ROUTING.............. G .... 38 SYSTEM CIRCUITS ............................ H .... 50 GROUND POINT ............................... I .... 370 POWER SOURCE (Current Flow Chart) . J .... 378 CONNECTOR LIST............................ K .... 388 1 BRZ (G4400BE) M PP 2 BRZ (G4400BE) 3 BRZ (G4400BE) M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M 4 BRZ (G4400BE) M 5 BRZ (G4400BE) 6 BRZ (G4400BE) PP PP PP PP PP 7 BRZ (G4400BE) M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M 8 BRZ (G4400BE) PP M -

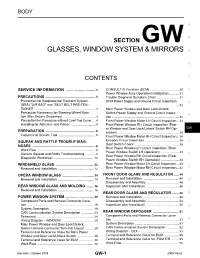

Glasses, Window System & Mirrors

BODY A B SECTION GW GLASSES, WINDOW SYSTEM & MIRRORS C D CONTENTS E SERVICE INFORMATION ............................ 3 CONSULT-III Function (BCM) .................................30 F Power Window Auto Operation Initialization ............31 PRECAUTIONS ................................................... 3 Trouble Diagnosis Symptom Chart ..........................31 Precaution for Supplemental Restraint System BCM Power Supply and Ground Circuit Inspection G (SRS) "AIR BAG" and "SEAT BELT PRE-TEN- ....32 SIONER" ...................................................................3 Main Power Window and Door Lock/Unlock Precaution Necessary for Steering Wheel Rota- Switch Power Supply and Ground Circuit Inspec- H tion After Battery Disconnect .....................................3 tion ...........................................................................32 Precaution for Procedure without Cowl Top Cover...... 4 Front Power Window Motor LH Circuit Inspection.... 33 Handling for Adhesive and Primer ............................4 Front Power Window RH Circuit Inspection (Pow- er Window and Door Lock/Unlock Switch RH Op- GW PREPARATION ................................................... 5 eration) ....................................................................34 Commercial Service Tool ..........................................5 Front Power Window Motor RH Circuit Inspection.... 34 SQUEAK AND RATTLE TROUBLE DIAG- Encoder Circuit Inspection .......................................36 J Door Switch Check ..................................................38 -

Nissan Security+Plus Extended Protection Plans

EXTENDED PROTECTION PLANS Enjoy peace of mind with superior benefits and protection Protect your Investment 0% Consumer Financing Plan Available Each year, more and more sophisticated No Qualification — Convenient Terms 1 3 5 technology is built into vehicles to improve their 2 4 R safety, performance, comfort and value. These same innovations help to increase the vehicle’s reliability. However, if something does go wrong, Factory-trained Technicians & Advanced the necessary repairs can be more complex and Diagnostic Equipment Maximize Your costly than they were 5 or 10 years ago. Nissan’s Safety and Reliability 1 3 5 2 4 R 1 3 5 2 4 R 1 3 5 Average Repair2 4 R Estimates* 1 3 5 2 4 R Air Conditioning Power Window $915 Motor Engine $378 Alternator $6,328 $689 Timing Chain $1,041 1 3 5 2 4 R 1 3 5 2 4 R 1 3 5 1 3 5 1 3 5 2 4 R Fuel Pump 2 4 R 2 4 R Transmission $607 Brake Caliper Rack & Pinion Control Arm Starter $3,325 $455 $1,272 $478 $401 *Image is for illustration purposes only. Repair costs are based on the 2017 Rogue. • Protect essential vehicle systems • Superior parts and service designed beyond your factory warranty — up exclusively for your Nissan to 8 years and 120,000 miles • Choose Gold Preferred for the • Convenient and economical ultimate in peace-of-mind coverage that guards against the protection for your new or rising cost of repairs pre-owned Nissan Why Security+Plus? For 30 years, we’ve provided Service You Can Trust - comprehensive, factory-backed coverage for Nissan Owners and repairs at any authorized Nissan dealership nationwide. -

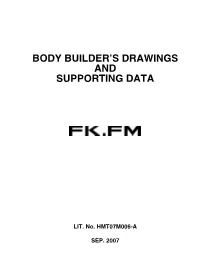

Body Builder's Drawings and Supporting Data

BODY BUILDER’S DRAWINGS AND SUPPORTING DATA LIT. No. HMT07M006-A SEP. 2007 INTRODUCTION This book has been designed to provide information for body and equipment manufacturers who mount their products on FK, FM chassis. We believe that all the detailed information which is essential for that purpose is contained in this book, but if you require any additional data or information, please contact : MITSUBISHI FUSO TRUCK OF AMERICA, INC. 2015 Center Square Road, Logan Township, NJ 08085 (Phone : (856) 467-4500) The specifications and descriptions contained in this book are based on the latest product information at the time of publication, but since the design of Mitsubishi-Fuso truck is continuously being improved, we must reserve the right to discontinue or change at any time without prior notice. COMPLIANCE WITH FEDERAL MOTOR VEHICLE SAFETY STANDARDS The federal government has established Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) for various categories of motor vehicles and motor Vehicle equipment under the provisions of the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966. The Act imposes important legal responsibilities on manufacturers, dealers, body builders and others engaged in the marketing of motor vehicles and motor vehicles equipment. Vehicles manufactured by Mitsubishi FUSO Truck & Bus Corporation (MFTBC) for the subsequent installation of commercical bodies are classified as incomplete vehicles. These vehicles fully comply with certain applicable Motor Vehicles Safety Standards, and partially (or do not) comply with others. They cannot be certified fully because certain components which are required for certification are not furnished. Under present federal regulations, vehicles completed from these units are required to meet all applicable standards in effect on the date of manufacture of the incomplete vehicles, the date of final completion, or date between those two dates, as determined by their final configuration. -

Ethics: an Alternative Account of the Ford Pinto Case

Ethics: An Alternative Account of the Ford Pinto Case Course No: LE3-003 Credit: 3 PDH Mark Rossow, PhD, PE, Retired Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] © 2015 Mark P. Rossow All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any manner without the written permission of the author. 1. Introduction 1.1 Conventional account The Ford Pinto case is today considered a classic example of corporate wrong-doing and is a mainstay of courses in engineering ethics, business ethics, philosophy, and the sociology of white- collar crime. The conventional account of the case goes something like this: In the mid-1960’s, Ford decided to rush a new subcompact car, the Pinto, into production to meet the growing competition from foreign imports. Because development was hurried, little time was available to modify the design when crash tests revealed a serious design defect: to provide adequate trunk space, the gas tank had been located behind rather than on top or in front of the rear axle. As a result, the Pinto was highly vulnerable to lethal fires in rear-end collisions and was in fact a “fire trap” and a “death trap.” Ford decided to ignore the defect anyway, because re-design would have delayed the entry of the car into the market and caused a potential loss of market share to competitors. As reports of fire- related deaths in Pintos began to come in from the field and as further crash tests re- affirmed the danger of the fuel-tank design, Ford decision-makers made an informed and deliberate decision not to modify the design, because doing so would harm corporate profits. -

August 19, 2003 Honorable Jeffrey Runge, M.D., Administrator National

August 19, 2003 Honorable Jeffrey Runge, M.D., Administrator National Highway Traffic Safety Administration U.S. Department of Transportation 400 Seventh Street, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20590 PETITION For more than thirty years, NHTSA has had the opportunity to prevent power window incidents inflicting death and injury by requiring manufacturers to install proper preventive mechanisms, but has neglected to do so. Since FMVSS 118 took effect on February 1, 1971, at least 33 children have been killed1 and thousands more children and adults have been injured2 by power windows. These tragedies could have been prevented had manufacturers been required to install fail-safe technology to ensure that occupants could not be trapped in rising windows. Such technology is now widely and voluntarily employed in the European market, even by the automakers that have vigorously opposed such requirements in the United States. The Center for Auto Safety (CAS), Public Citizen, KIDS AND CARS (KAC), Consumer Federation of America (CFA), Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, the Zoie Foundation, the Trauma Foundation, and Consumers for Auto Reliability and Safety (CARS) petition the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) pursuant to 49 C.F.R. 552 to initiate rulemaking for the purpose of amending Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard 118 (FMVSS 118) to protect children from death and injury involving power-operated windows and roof panels. Petitioners request that NHTSA propose modifying FMVSS 118 to require anti-trap mechanisms in all motor vehicles that would reverse the direction of power window operation when an obstruction is encountered. Petitioners also request that NHTSA propose requiring all manufacturers to install power window controls to prevent inadvertent engagement by occupants. -

2021-Carlisle-Ford-Nationals

OFFICIAL EVENT GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 WELCOME 7 FORD MOTOR COMPANY 9 SPECIAL GUESTS 2021-22 EVENT SCHEDULE 10 EVENT HIGHLIGHTS AUTO MANIA JAN. 15-17, 2021 ALLENTOWN PA FAIRGROUNDS NPD SHOWFIELD JAN. 14-16, 2022 13 HIGHLIGHTS WINTER CARLISLE NEW EVENT! AUTO EXPO FEATURED VEHICLE CARLISLE EXPO CENTER JAN. 28-29, 2022 17 DISPLAY: BUILDING Y WINTER AUTOFEST CANCELLED FOR 2021 FEATURED VEHICLE LAKELAND 18 DISPLAY: STROPPE SUN ’n FUN, LAKELAND, FL FEB. 25-27, 2022 REUNION LAKELAND WINTER FEB. 19-20, 2021 FEATURED VEHICLE COLLECTOR CAR AUCTION FEB. 25-26, 2022 20 DISPLAY: BUILDING T SUN ’n FUN, LAKELAND, FL SPRING CARLISLE APRIL 21-25, 2021* 25 OFFICIAL CARLISLE CLUBS PRESENTED BY EBAY MOTORS CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS APRIL 20-24, 2022 EVENT SCHEDULE SPRING CARLISLE APRIL 22-23, 2021 26 COLLECTOR CAR AUCTION CARLISLE EXPO CENTER APRIL 21-22, 2022 28 EVENT MAP IMPORT & PERFORMANCE NATS. MAY 14-15, 2021 CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS MAY 13-14, 2022 30 VENDORS: BY SPECIALTY FORD NATIONALS JUNE 4-6, 2021* PRESENTED BY MEGUIAR’S 34 VENDORS: A-Z CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS JUNE 3-5, 2022 GM NATIONALS JUNE 25-26, 2021 40 ABOUT OUR PARTNERS CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS JUNE 24-25, 2022 JULY 9-11, 2021* 46 CONCESSIONS CHRYSLER NATIONALS CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS JULY 15-17, 2022 49 CARLISLE EVENTS APP TRUCK NATIONALS AUG. 6-8, 2021* PRESENTED BY A&A AUTO STORES CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS AUG. 5-7, 2022 51 HELPFUL INFORMATION & POLICIES CORVETTES AT CARLISLE AUG. 26-28, 2021 PRESENTED BY TOP FLIGHT AUTOMOTIVE 53 AD INDEX CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS AUG. -

The Automobile Cars in My Life— 40 Horsepower to 400

Part II: The Automobile Cars in My Life— 40 Horsepower to 400 by Arthur D. Delagrange, Massachusetts Beta ’64 BEGAN WORKING ON CARS before I had my with little or no pressure. Dad kept a running sample in a driver’s license, partly successfully. Getting my bottle outside; when it froze, he added more methanol. It own car was certainly one of the milestones in my had a DC generator with a mechanical (relay) regulator and young life. My love of cars has since diminished a six-volt system. Idling or in heavy traffic the battery only in proportion to my ability to drive them and would run down, but you kept the headlights on during a work on them. I have been fortunate to own many long trip to avoid overcharging. Starting in cold weather ioutstanding cars, both good and bad. Had I always been was iffy. It had a manual choke to enrich the mixture for able to keep what I had in good condition, I would have starting. It also had an auxiliary hand throttle, a poor-man’s quite a collection—but I drove these cars daily, often to the cruise control. The oil filter, an option, was not full-flow. point of exhaustion, and usually had to sell one to buy an- Pollution controls were zero. Top speed was above 90, quite other. a thrill on cotton-cord tires. My personal memories constitute a good cross-section Transmission was a manual three-speed. Rear axle was of the modern American automobile. Much of what I would live (unsprung differential) with a single transverse leaf like to have owned, but didn’t, some friend did.