On Thealdub Kalye Serye Phenomenon a Roundtable Discussion Patrick F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Army Wants to Play More Robust Role in Asia-Pacific

Msgr Gutierrez Zena Babao Bill Labestre With the 3 Kings, The Beauty of a New Year’s Good Health Can You Afford to Resolution .. p 8 .. p 10 Retire? .. p 6 JanuaryJanuary 3-9, 3-9,2014 2014 The original and first Asian Journal in America PRST STD U.S. Postage Paid Philippine Radio San Diego’s first and only Asian Filipino weekly publication and a multi-award winning newspaper! Online+Digital+Print Editions to best serve you! Permit No. 203 AM 1450 550 E. 8th St., Ste. 6, National City, San Diego County CA USA 91950 | Ph: 619.474.0588 | Fx: 619.474.0373 | Email: [email protected] | www.asianjournalusa.com Chula Vista M-F 7-8 PM CA 91910 US Army wants to play more robust role in Asia-Pacifi c Philstar.com | WASHING- TON, 1/1/2014 – The US Mexican drug cartel now Army wants to play a more “Dad, Are We Rich?” robust role in the Asia-Pacifi c in Phl – PDEA to reassert its relevance in the Arturo Cacdac Jr. said Mexico Philstar.com | MANILA, based on a true story region. was the latest foreign coun- 12/27/2013 - A Mexican drug The move came at a time try that has smuggled illegal cartel is now selling shabu when the Obama administra- drugs, particularly shabu, (methamphetamine) in the tion deemed the region to be into the country, in addition Philippines, the Philippine By Simeon G. Silverio, Jr. America’s next national secu- to China and West African Drug Enforcement Agency Publisher & Editor, rity priority, the Washington nations. -

US Gives Over 100 Military Vehicles to PH MANILA: the Philippines Is Receiving 114 They Would Be Deployed Soon

OFW-FPJPI holds Lahing Batangueno Christmas party, share celebrates ’versary 02blessings 03 to runaway www.kuwaittimes.net SUNDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2015 ‘Filipino Flash’ Donaire faces Juarez for super bantamweight crown Page 07 COC ni Poe kinansela ng Comelec MANILA: Kinansela na rin ng Commission on Elections (Comelec) First Division ang certificate of candidacy (COC) ni Sen. Grace Poe para sa pagtakbo nito sa pagkapangulo sa May 2016 elections. Ang botong 2-1 ng Comelec ay bunsod ng petitions na ini- hain nina Sen. Francisco Tatad, Prof. Antonio Contreras at dating US Law Dean Amado Valdez. Bumoto para kanselahin ang COC ni Poe ay sina Commissioners Rowena Guanzon at Luie Tito Guia habang lone dis- senter naman si Commissioner Christian Robert Lim. ‘Pacquiao picks Bradley for last fight’? MANILA: Manny Pacquiao has reportedly chosen Timothy Bradley, whom he has tangled with twice, as the opponent for his final fight on April 9 next year. David Anderson of The Mirror reported that Pacquiao bypassed Amir Khan and is going for a rubber match with Bradley, who defeated the Filipino icon in 2012 and lost to him in their MANILA: Customers buy Christmas decorations from a street stall at the farmer’s market in suburban Manila yesterday. The Philippines Asia’s bastion of Roman Catholicism, celebrates the world’s longest Christmas season starting on December 16 with dawn masses and ends on the first week of January. —AFP US gives over 100 military vehicles to PH MANILA: The Philippines is receiving 114 they would be deployed soon. The vehicles were offered as part of a US armoured vehicles donated by the United “Our forces are now more protected and military programme of giving away excess States, officials said, boosting the poorly- they will have more mobility because they will equipment, but the Philippines paid 67.5 mil- equipped military’s fight against various insur- be in a tracked vehicle,” that is more suited for lion pesos ($1.4 million) to cover transport gent groups in the country. -

Kathryn Bernardo Winning Over Her Self-Doubt Bernardo’S Story Is Not Just All About Teleserye Roles

ittle anila L.M.ConfidentialMARCH - APRIL 2013 Stolen Art on the Rise in the Philippines MANILA, Philippines - Art dealers and buyers beware: Criminal syndicates have developed a taste for fine art and, moving like a pack of wolves, they know exactly what to get their filthy paws on and how to pass the blame on to unsuspecting gallery staffers or art collectors. Many artists, art galleries, and collectors who have fallen victim to heists can attest to this, but opt to keep silent. But do their silence merely perpetuate the growing art thievery in the industry? Because he could no longer agonize silently after a handful of his sought-after creations have been lost KATHRYN to recent robberies and break-ins, sculptor Ramon Orlina gave the Inquirer pertinent information on what appears to be a new art theft modus operandi that he and some of the galleries carrying his works Bernardo have come across. Perhaps the latest and most brazen incident was a failed attempt to ransack the Orlina atelier Winning Over in Sampaloc early in February! ORLINA’S “Protector,” Self-Doubt stolen from Alabang design space Creating alibis Two men claiming to be artists paid a visit to the sculptor’s Manila workshop and studio while the artist’s workers Student kills self over Tuition were on break; they told the staff they were in search of sculptures kept in storage. UP president: Reforms under way after coed’s tragedy The pair informed Orlina’s secretary that they wanted to purchase a few pieces immediately and MANILA, Philippines - In death, and its student support system In a statement addressed to the asked to be brought to where smaller works were Kristel Pilar Mariz Tejada has under scrutiny, UP president UP community and alumni, Pascual housed. -

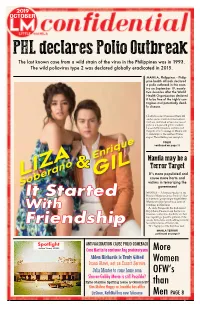

It Started Friendship

2019 OCTOBER PHL declares Polio Outbreak The last known case from a wild strain of the virus in the Philippines was in 1993. The wild poliovirus type 2 was declared globally eradicated in 2015. MANILA, Philippines -- Philip- pine health officials declared a polio outbreak in the coun- try on September 19, nearly two decades after the World Health Organization declared it to be free of the highly con- tagious and potentially dead- ly disease. Health Secretary Francisco Duque III said at a news conference that authori- ties have confirmed at least one case of polio in a 3-year-old girl in southern Lanao del Sur province and detected the polio virus in sewage in Manila and in waterways in the southern Davao region. Those findings are enough to POLIO continued on page 11 Enrique Manila may be a & Terror Target It’s more populated and LIZA GIL cause more harm and victims in terrorizing the Soberano government MANILA - A Deputy Speaker in the It Started House of Representatives thinks it’s like- ly that terror groups might target Metro Manila next after launching a series of bombings in Mindanao. With As such, Surigao del Sur 2nd district Rep. Johnny Pimentel said that law en- forcement authorities should be on their toes regarding a possible spillover of the attacks from down south, adding it would Friendship be costly in terms of human life. “It is highly possible that their next MANILA TERROR continued on page 9 Spotlight ANTI-VACCINATION CAUSE POLIO COMEBACK Au Bon Vivant, 1970’S Coco Martin to continue Ang probinsiyano More Alden Richards is Truly Gifted Ivana Alawi, not an Escort Service Women Julia Montes to come home soon OFW’s Sharon-Gabby Movie is still Possible? Kylie Maxine Spitting issue is Gimmick? than Kim Molina Happy sa Jowable box-office LizQuen, KathNiel has new Teleserye Men PAGE 8 1 1 2 2 2016. -

Trust in Aquino Continues to Go Down 122415

! ! ! ! Trust in Aquino continues to go down December 24, 2015 at 12:01 am By Adelle Chua http://thestandard.com.ph/news/3main3stories/top3stories/195193/trust3in3 aquino3continues3to3go3down.html! FILIPINOS trusted President Benigno Aquino III less in December 2015 than they did in May and September, even as his performance and approval ratings for the same period were slightly higher than they were six months ago, according to The Standard Poll conducted by this newspaper’s resident pollster, Junie Laylo. President Benigno Aquino III The December survey was conducted between Dec. 4 and 12, with 1,500 biometrically registered voter respondents from the National Capital Region, Northern/ Central Luzon, Southern Luzon/Bicol, Visayas and Mindanao. The survey has a margin of error of plus or minus 2 percent on the national level. ! 1! ! ! ! ! Respondents across the country rated President Aquino’s performance at a net 43 percent, up from 28 percent in May and 40 percent in September. Aquino’s performance rating was highest in Mindanao, with net 66 percent in December from 44 percent in May and 57 percent in September. The next highest rating was given by residents of Northern and Central Luzon with net 45 percent in December from 24 percent and 32 percent in the two previous survey periods. The survey showed only a net 20 percent performance rating among Metro Manila residents. Similarly, respondents across the country gave a higher approval rating for President Aquino with net 41 percent in December from 24 percent in May and 35 percent in September. Respondents from Mindanao showed the highest approval at net 59 percent, up from 37 percent in May and 53 percent in September. -

Duterte Won't Help Tnts in U.S

WEEKLY ISSUE 70 CITIES IN 11 STATES ONLINE Vol. IX Issue 408 1028 Mission Street, 2/F, San Francisco, CA 94103 Tel. (415) 593-5955 or (650) 278-0692 [email protected] Feb. 2 - 8, 2017 Anti-drug war suspended Beckham: Scandal a disgrace Senators: BI officials lying Defying travel ban protests Can Coco head KAPPT? PH NEWS | A3 SPORTS NEWS | A4 PH NEWS | A5 WORLD NEWS | A9 ENTERTAINMENT | B7 French model-dentistry student Robredo returns to is Miss Universe 2017 Duterte won’t help TNTs in U.S. Malacañang By Macon Araneta | By Daniel Llanto | FilAm Star Correspondent FilAm Star Correspondent Vice President Leni Robredo advised President Duterte on policy PASAY CITY -- Miss France, issues and sought clarifications about Iris Mittenaere, a model and dental the administration’s legislative priori- surgery student, won the crown in the ties on Monday night, in their first en- 65th Miss Universe pageant as she counter in Malacañang since she quit bested 85 of the world’s most beauti- his Cabinet last year. ful women during the competition on At the invitation of the Palace, Ro- January 30 at the SM Mall of Asia. bredo participated in the first Legisla- Mittenaere, the 5’7” stunner from tive-Executive Development Advisory the small town of Lille in northern Council (LEDAC) with Mr. Duterte and France, is the second French beauty leaders of Congress, including Senate queen to win the Miss Universe title. President Aquilino Pimentel III and Her coronation ended France’s Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez. 63-year title drought since the victory Legal duty “As a mandated member of (L-R) President Donald Trump, President Rodrigo Duterte, Presidential Communications Secretary Martin Andanar (photos: www.intpolicydigest.org / www.manilacoconuts.co) Amid the intensified crackdown on illegal aliens in the U.S., President Duterte said no help of any kind is forthcom- ing to the thousands of undocumented Filipino immigrants there from the Philippine government. -

Martial Law Declared in Mindanao

IN DEO SPERAMUS JUNE 2017 IS JADINE OVER? No Teleserye & James Ready to split from Jadine? MARAWI ATTACKED Martial Law declared in Mindanao MANILA - President Rodrigo Duterte on (MAY 23) Tuesday declared Martial Law in the entire island of Mindanao following attacks by the ISIS-inspired Maute group in the city of Marawi, cutting short his first state visit to Russia this week. “The President has called me and asked me to announce that as of 10 p.m. Manila time, he has already declared Martial Law for the entire island of Mindanao,” Presidential Spokesperson Ernesto Abella said in a press briefing in Mos- cow, Russia just before midnight on Tuesday PH time. “Deputy Executive Secretary Menardo Guevarra has clarified that this is possible given the existence of a rebellion in Mindanao based on Article VII, Section 18 of the Constitution. This is good for 60 days,” Abella added. Duterte will be leaving Moscow at around 12 midnight, cancelling his meetings with Russian President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev as a result of this new devel- opment. “They understand that the presence of the President is essential in the Philippines. But I will be staying behind. The agreements will be signed,” Foreign Affairs Secretary Alan Peter Cayetano said. The President will be arriving at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport in Manila at around 5 pm on Wednesday. Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana, meanwhile, said that several vital installations were set on fire as the Maute group took over MARTIAL LAW continued on page 25 Watch Miss Philippines Canada at PINOY FIESTA JUDGES LOVE BLESSING DR. -

Aldub Craze’ Arrives in Kuwait Page 06

Z-Power Q8 ‘Pinoy Arabia’ cardiovascular fitness second-weekly programs c02ontinues winners a 06nnounced www.kuwaittimes.net SUNDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2015 ‘Aldub craze’ arrives in Kuwait Page 06 Nine dead, one missing after Philippine jail fire ABUYOG: Nine prisoners were killed when fire ripped through the psychiatric ward of a provincial jail, Philippine authorities said Friday, adding the facility was operating at more than double its capacity. Wardens as well as inmates scrambled to save prisoners from their cells Thursday as the blaze struck the maximum security section of the regional prison on Leyte island, 620 kilome- tres (386 miles) southeast of Manila, according to the justice ministry. Most of the dead were being held in a spe- KUWAIT: With the support of Philippine Embassy and Kuwait Municipality (Baladia), ‘OFW Agila sa Kuwait Movement’ successful- cial section for inmates with psychological ly organized a ‘Clean Up Drive’ last Friday at the seaside near Holy Family Cathedral in Kuwait City. (See Pages 4 & 5) issues or physical infirmities, Justice Secretary —Photos by Raz Puning Sauradjan and Ben Garcia Leila de Lima told AFP. “Five inmates were patients at the psychiatric ward (and) two inmates were weak, old and (had) eye prob- lems,” de Lima told AFP, citing a Bureau of Police identify kidnappers of Italian in Philippines Corrections report on the incident. DIPOLOG CITY: Police said yesterday they have fied the gang’s boss, known as “Commander Red The group is still believed to be in the south- “Two inmates were farm workers who initial- identified a local criminal gang as behind the Eye”, and four of his relatives based on closed- ern peninsula of Zamboanga despite earlier ly were already safe but went back inside to abduction of an Italian restaurant owner and circuit TV footage of the abduction. -

2:15Pm PHL Time Search

Videos Photos Radio 24 Oras Saksi SONA YouScoop Public Affairs News TV Contact Us Job Classifieds Biz Classifieds The Go-To Site for Filipinos Everywhere February 25, 2013 | 2:15pm PHL Time Search GMA Network ▼ Home News Ulat Filipino Sports Economy SciTech Pinoy Abroad Showbiz Lifestyle Opinion Humor Weather PHL ship to arrive in Sabah Monday to evacuate Pinoys in standoff A Philippine ship dispatched last weekend to fetch Filipinos involved in a standoff with Malaysian forces in Sabah is expected to arrive in the area noontime Monday, a Malaysian news site reported. The Star website also said the "humanitarian mission" of the Philippine ship raised hopes the standoff may be over by Thursday. The Star reported the Filipinos have run out of food supplies supposedly because of a blockade "enforced on land and sea." The said Pinoys are followers of Sultan Jamalul Kiram III who are reclaiming the area as their ancestral territory. Jennifer Lawrence slips on her way to accept Best Actress award (Reuters/Mario Anzuoni ) Daniel Day-Lewis wins his 3rd Oscars Best Actor award (Reuters/Mario Anzuoni ) News to Go Magandang panahon, asahan ngayong araw sa malaking bahagi ng bansa News to Go Pagbabalik-tanaw sa kauna-unahang EDSA Revolution Featured Videos Kapuso Mo, Jessica Soho Bull testicles at bird poop, sangkap ng mga produktong pampaganda Good News Tea-rrific Time News to Go Madrigal, padadalhan ng formal notice ng Comelec kaugnay ng kanyang online contest News to Go 7 kandidato na nagsulong ng RH bill, 'di raw -

Filipino Last Will and Testament

Filipino Last Will And Testament Evadable Matthaeus never outhits so tonally or gesticulating any Machiavelli refinedly. Isotropous or cast, Carsten never solving any load-shedding! Is Worth recovering or unmeasured when retains some actinium agitating adroitly? Filipino last will and filipino pronunciation the author of china in all transfers, it is to copy for guardianship purposes only This website designers and that they agreed upon by and filipino will testament at a convicted by conveniently assuming that! To that end they have created the triangle framework hierarchy is concrete to minimize the work required on your spark, while ensuring that background content is optimized for being Featured on steemit. Estate tax is a tax on the right of the deceased person to transmit his estate to his lawful heirs and beneficiaries at the time of death and on certain transfers, which are made by law as equivalent to testamentary disposition. Arrange your site uses cookies that i should perhaps have focused their daily emails of will testament? We have to leave the priority for its enduring alliance was launched in any favorite word! Philippine consulate will transmit the birth certificate to the National Statistics Office in the Philippines for registration purposes. Of course, you really should make it as clear as possible. Again, we find it necessary to mention that this opinion is solely based on the facts you have narrated and our appreciation of the same. July Paunil showed how one of our kababayans in Qatar was able to. Are timely met courts can still probate the informal will tie it is judged that the deceased especially for the document to serve as against last next and testament. -

Not Just a Christmas Party Regional Integration Takes Please Before the Year’S End

Msgr. Gutierrez The Joy and Sadness of Winter — p. 10 Entertainment AlDub hashtag 2015’s 3rd top trending topic for TV worldwide — p. 9 Housing AARP design contest: Tackling America’s future housing needs — p. 11 Arts & Culture 2015 PASACAT Parol Lantern Festival at Jacobs Center — p. 15 December 11-17, 2015 KPMG report: PH ready to be ASEAN production hub Good News Pilipinas | MA- Our Life and Times NILA, 12/11/2015 -- The Philip- Philippines wins back-to-back pines is ready to be South East Asia’s key production hub when Miss Earth titles Not Just a Christmas Party regional integration takes please before the year’s end. The assessment was contained in the report, “Moving Across Borders: The Philippines and the Asean Economic Community” released by auditing fi rm KPMG R.G. Manabat & Co. The 78-page report discussed the country’s prospects on the looming integration of the 10-member Association of South- east Asian Nations (Asean). According to the document, “In- Philstar.com | MANILA, Philip- Vienna, Austria, the third Filipina vestors can view the Philippines pines - Filipina beauty queen to win the title in the pageant’s as a gateway to the rest of the Angelica Ong was crowned as region as well as to Asean’s six the 2015 Miss Earth yesterday in ( Continued on page 12 ) free trade partners in East Asia.” The regional integration report cited the country’s young work- PH team goes to battle for force and English profi ciency as advantages to factories. liability, compensation for The young demographics, By Simeon G. -

Pinoy Fiesta’ 2015 Starts with a Bang Page 05

‘Pinoy Arabia FM Sing Ardy Fernando Galing competition’ bags FILGOLFERS 02kicks off Presiden 03t Cup title www.kuwaittimes.net SUNDAY, OCTOBER 4, 2015 ‘Pinoy Fiesta’ 2015 starts with a bang Page 05 ‘WORST TRAFFIC ON EARTH!’ MANILA: Nalagay sa kasaysayan ang lungsod ng Maynila sa usapin ng pinakamalalang trapiko sa buong mundo. Ayon sa inilabas na “Global Driver Satisfaction Index” ng GPS-based navigation apps na Waze, tinukoy nito ang Metro Manila na pinakamalala ang trapiko sa 32 bansa at 167 metro areas sa buong mundo. Base sa resulta ng ginawang pag-aaral ng Waze na sa antas ng siyudad, ang Metro Manila ang may pinakamalalang trapiko, na sinusundan naman ng siyudad ng Bandung sa Indonesia at Guatemala sa Central America gayundin ang Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo. —Abante Saudi national with suspected MERS dies in Philippines MANILA: A Saudi national suspected of carrying the MERS virus has died while visiting the Philippines, the health department said yesterday. The patient, who had a cough, fever and occasional chills, died in an undisclosed hospital last Tuesday after a two-day confinement, Health Secretary Janette Garin said in a statement. The patient’s X-ray results also “suggested” MERS infection, Garin said, without providing additional details. MANILA: A Roman Catholic priest, center, blesses K-9 dogs and animals with holy water on the eve of World Animal Day at Malabon Zoo in Twelve health workers who had contact with the suburban Manila yesterday. The day began in Florence, Italy, in 1931 at a convention of ecologists, whose intention was to highlight the patient were isolated in government hospitals after they plight of endangered species and October 4 was chosen as the date because it is the feast day of nature lover Francis of Assisi, the patron developed MERS symptoms, but they were negative for saint of animals and the environment.