Turin: the Vain Search for Gargantua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Op 121 Elenco Sportelli Torino

COMUNE CAP INDIRIZZO ENTE BENEFICIARIO REFERENTE TEL E-MAIL ALMESE 10040 P.zza Martiri 36 C.I.P.A.-A.T. PIEMONTE PEROTTI ALESSANDRO 0119350018 [email protected] BUSSOLENO 10053 VIA TRAFORO N.12/B ASSOCIAZIONE REGIONALE UE.COOP PIEMONTE ORNELLI FABIO 0122647394 CALUSO 10014 V. Bettoia 50 C.I.P.A.-A.T. PIEMONTE ROSSI SIMONE 0119832048 [email protected] CALUSO 10014 VIA BETTOIA, 70 ASSOCIAZIONE REGIONALE GRUPPI COLTIVATORI SVILUPPO DOTTO PAOLO 0119831339 [email protected] CARIGNANO 10041 Vicolo Annunziata 3 ORGANISMO DI ASSISTENZA TECNICA AGRICOLA LIBERI PROF BONIFORTE ALESSANDRO 011/9770805 [email protected] CARMAGNOLA 10022 V. GIOLITTI 32 C.I.P.A.-A.T. PIEMONTE DESTEFANIS DIEGO 0119721081 [email protected] CARMAGNOLA 10022 VIA GOBETTI 7 ENTE REGIONALE PER L'ADDESTRAMENTO E PER IL PERFEZIOBARACCO ROBERTO 119713424 [email protected] CARMAGNOLA 10022 Via Papa Giovanni XXIII, 2 ASSOCIAZIONE REGIONALE GRUPPI COLTIVATORI SVILUPPO ROMANO PAOLO 0119721715 [email protected] CARMAGNOLA 10022 Via S. Francesco di Sales 56 OATA GAY PIETRO PAOLO 011/9713874 [email protected] CARMAGNOLA 10022 VIA SOMMARIVA, 31/9 CONSORZIO GESTCOOPER MELLANO SIMONE 0119715308 [email protected] CHIERI 10023 V. San Giacomo 5 C.I.P.A.-A.T. PIEMONTE MAURO NOE' 011 9471568 [email protected] CHIERI 10023 Via XXV Aprile, 8 ASSOCIAZIONE REGIONALE UE.COOP PIEMONTE FASSIO MANUELA 3357662283 CHIVASSO 10034 V. Italia 2 piano 1 C.I.P.A.-A.T. PIEMONTE MAURO NOE' 011 9113050 [email protected] CHIVASSO 10034 Via Lungo Piazza D'Armi, 6 ASSOCIAZIONE -

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE The Central Park in between Torino and Milano Original The Central Park in between Torino and Milano / Andrea, Rolando; Alessandro, Scandiffio. - STAMPA. - (2016), pp. 336- 336. ((Intervento presentato al convegno TASTING THE LANDSCAPE - 53rd IFLA WORLD CONGRESS tenutosi a TORINO nel 20-21-22 APRILE 2016. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2645620 since: 2016-07-26T10:24:06Z Publisher: Edifir-Edizioni Firenze Published DOI: Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 04 August 2020 TASTING THE LANDSCAPE 53rd IFLA WORLD CONGRESS APRIL • 20th 21st 22rd • 2016 TORINO • ITALY © 2016 Edifir-Edizioni Firenze via Fiume, 8 – 50123 Firenze Tel. 055/289639 – Fax 055/289478 www.edifir.it – [email protected] Managing editor Simone Gismondi Design and production editor Silvia Frassi ISBN 978-88-7970-781-7 Cover © Gianni Brunacci Fotocopie per uso personale del lettore possono essere effettuate nei limiti del 15% di ciascun volume/fascicolo di periodico dietro pagamento alla SIAE del compenso previsto dall ’ art. 68, comma 4, della legge 22 aprile 1941 n. 633 ovvero dall ’ accordo stipulato tra SIAE, AIE, SNS e CNA, CONFARTIGIANATO, CASA, CLAAI, CON- FCOMMERCIO, CONFESERCENTI il 18 dicembre 2000. Le riproduzioni per uso differente da quello personale sopracitato potranno avvenire solo a seguito di specifica autorizzazione -

Cento Torri (927.47

03/09/2019 Tra Chieri e Torino: ecco “Tramanda”, la fiber art tra passato e futuro - CentoTorri Accedi CHIERI e CHIERESE DINTORNI TROFARELLO CAMBIANO SANTENA MONCALIERI NICHELINO POIRINO CARMAGNOLA VILLASTELLONE DALLE PROVINCE TORINO CITTA’ METROPOLITANA ASTI e ASTIGIANO CUNEO e LA GRANDA ALBA LANGHE e ROERO ALESSANDRIA e MONFERRATO NOVARA VERCELLI BIELLA VCO SPORT SPORT QUI JUVE QUI TORO COMPRA e VENDI Pubblicità RALLY CHIERI NEWS Pubblicità Privacy https://www.100torri.it/?p=83523 2/10 03/09/2019 Tra Chieri e Torino: ecco “Tramanda”, la fiber art tra passato e futuro - CentoTorri Tra Chieri e Torino: 8° Memory Fornaca: Rally ecco “Tramanda”, la Lana spettacolare fiber art tra passato e futuro DI REDAZIONE · 17 APRILE 2019 IL CERCALAVORO. Le opportunità della settimana Per il – a cura di ALESSIA ARBA secondo anno consecutivo, all’Accademia PIEMONTE ARTE: Albertina delle Belle Arti di Torino, si svolge la CARMAGNOLA, ZAGO, Conferenza Stampa di Tramanda – il filo tra DENTISTI&ARTISTI, CHIERI, passato e futuro, manifestazione artistica Privacy https://www.100torri.it/?p=83523 3/10 03/09/2019 Tra Chieri e Torino: ecco “Tramanda”, la fiber art tra passato e futuro - CentoTorri internazionale organizzata dalla Città di Chieri e LEQUIO, VINOVO, SALUZZO… che inaugurerà nel mese di maggio. A 21 anni dalla 1^ Biennale di Trame d’Autore e dell’omonima Collezione Civica, oggi espressione di un Progetto per l’Osservazione Camp SAK 150 Event - sacco a … Salewa Fusion Hybrid 4 SB -sac… CLICCA CLICCA della Fiber Art e del Medium Tessile nell’Arte Contemporanea, la Città di Chieri, con i patrocini di MiBAC Ministero per i Beni e le PASSIONE FUMETTI: 5 è il Attività Culturali, della Regione Piemonte e numero perfetto, dal della Città Metropolitana di Torino, anche graphic novel al film. -

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

2013 Torino Italy OOO «CMK» - Site production in Russia, Kaluga CELLINO S.r.l. This presentation is the property of Cellino S.r.l. and its subsidiaries and is strictly Strada del Portone, 171/12 confidential. It contains information intended only for the person to whom it is transmitted. With receipt of this information, recipient acknowledges and 10095 Grugliasco (TO – Italy) agrees that: (i) this document is not intended to be distributed, and if distributed inadvertently, will be returned to the Cellino S.r.l. as soon as possible; (ii) the recipient will not copy, fax, reproduce, divulge, or distribute this confidential phone +39.011.301.26.11 information, in whole or in part, without the express written consent of Cellino S.r.l.; (iii) all of the information herein will be treated as confidential material with fax +39.011.314.94.79 no less care than that afforded to its own confidential material. BRAZIL ITALY POLONIA INDIA SAÕ PAOLO Unit 1 Unit 2 Unit 3 Unit 4 (TO) (TO) (TO) (TO) Mumbai SHL CELLINO RUSSIA IntekCM Co.Proget Celmac OCM Badve-Cellino (KIELCE) (Settimo- (Rivalta- (Poirino- (Nusco- TO) TO) TO) AV) (PUNE) KALUGA Employees 2013: nr. 1050 2013 Unit 1 & 2 – Grugliasco - •COMPONENTS FOR - TRUCKS, COMMERCIAL VEHICLES Bruino (To) Italy •AUTOMOTIVE, MATERIAL HANDLING Unit 3 & 4 Torino -Chivasso •PAINTING PLANT FOR CHASSIS COMPONENTS (To) Italy •TRUCKS/AUTOMOTIVE CELMAC SRL - Poirino (To) •COMPONENTS FOR TRUCKS: FRAMES – CROSS MEMBER Italy INTEK CM- Settimo Torinese •TANKS - BODY FOR ELEVATOR (To) Italy •BODY FOR AIR COMPRESSOR -

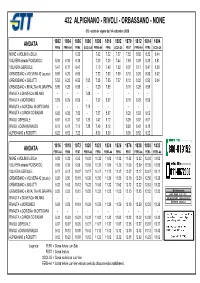

1432 Alpignano-Orbassano-None

432 ALPIGNANO - RIVOLI - ORBASSANO - NONE 010 orario in vigore dal 14 settembre 2020 ANDATA 1802 1804 1806 1890 1808 1810 1892 1870 1812 1814 1894 FER6 FER5-A4 FER6 SCOLG5 FER5-A4 FER6 SCOLG5 FEST FER5-A4 FER6 SCOLG5 NONE v.MOLINO/v.SOLA 6.32 7.02 7.32 7.37 7.52 8.02 8.32 8.44 VOLVERA strada PIOSSASCO 5.39 6.09 6.39 7.09 7.39 7.44 7.59 8.09 8.39 8.51 VOLVERA GERBOLE 5.47 6.17 6.47 7.19 7.49 7.52 8.07 8.17 8.47 8.59 ORBASSANO v.VOLVERA 42 (scuole) 5.50 6.20 6.50 7.23 7.53 7.55 8.10 8.20 8.50 9.02 ORBASSANO v.GIOLITTI 5.52 6.22 6.52 7.03 7.25 7.55 7.57 8.12 8.22 8.52 9.04 ORBASSANO v.RIVALTA/v.M.GRAPPA 5.55 6.25 6.55 - 7.29 7.59 8.15 8.25 8.55 RIVALTA v.GIAVENO/v.MILANO - - -7.08- - - -- RIVALTA v.MORIONDO 5.59 6.29 6.59 - 7.32 8.02 8.19 8.29 8.59 RIVALTA v.GORIZIA/v.M.ORTIGARA - - -7.15- - - -- RIVALTA v.CANONICO BALMA 6.02 6.32 7.02 - 7.37 8.07 8.22 8.32 9.02 RIVOLI OSPEDALE 6.07 6.37 7.07 7.23 7.42 8.12 8.26 8.37 9.07 RIVOLI v.DON MURIALDO 6.12 6.42 7.12 7.28 7.49 8.19 8.30 8.42 9.12 ALPIGNANO p.ROBOTTI 6.22 6.52 7.22 8.00 8.30 8.38 8.52 9.22 ANDATA 1816 1818 1872 1820 1822 1824 1826 1874 1828 1830 1832 FER5-A4 FER6 FEST FER5-A4 FER6 FER5-A4 FER6 FEST FER5-A4 FER6 FER5-A4 NONE v.MOLINO/v.SOLA 9.02 9.32 9.52 10.02 10.32 11.02 11.32 11.52 12.02 12.32 13.02 VOLVERA strada PIOSSASCO 9.09 9.39 9.59 10.09 10.39 11.09 11.39 11.59 12.09 12.39 13.09 VOLVERA GERBOLE 9.17 9.47 10.07 10.17 10.47 11.17 11.47 12.07 12.17 12.47 13.17 ORBASSANO v.VOLVERA 42 (scuole) 9.20 9.50 10.10 10.20 10.50 11.20 11.50 12.10 12.20 12.50 13.20 ORBASSANO v.GIOLITTI -

Grugliasco -Torino

Nuova linea Torino Lione Ipotesi di quadruplicamento in sede Avigliana - Torino Maggio 2018 Nuova linea Torino Lione Confronto tracciati Bussoleno Avigliana Stura Alpignano Avigliana Rebaudengo/Fossata Ferriera/Butigliera Alta Collegno Rosta Grugliasco Porta Susa Porta Nuova Quaglia – Le Gru S.Paolo Linea Diretta Orbassano S. Luigi 2 Nuova linea Torino Lione Quadruplicamento in sede 3 Esempio di sezioni (con e senza l’ipotesi di adeguamento del tracciato in corrispondenza di Corso Francia) Binari Limite sede Ingombro totale 4 Grugliasco - Torino EDIFICI DA DEMOLIRE EDIFICI CRITICI Km di tracciato PRINCIPALI CRITICITA' (di cui prod.) (di cui prod.) Bivio Pronda 10 (3) 10 (2) 2,2 Corso Torino Fermata FS Corso Francia Binari Limite sede Ingombro totale 5 Torino - Bivio Pronda 6 Grugliasco – Corso Torino Binari Limite sede Ingombro totale 7 Grugliasco - Fermata FS Binari Limite sede Ingombro totale 8 Grugliasco – Corso Francia Binari Limite sede Ingombro totale 9 Grugliasco -Torino Edificio da demolire Edificio critico 10 Collegno PRINCIPALI CRITICITA' EDIFICI DEMOLITI EDIFICI CRITICI Km di tracciato Corso Francia (necessiterà allargamento) 33 (6) 18 (3) 2,6 (di cui prod.) (di cui prod.) Via San Massimo – Certosa Viale XXIV maggio Via JF Kennedy Binari Limite sede Ingombro totale 11 Collegno – Corso Francia Binari Limite sede Ingombro totale 12 Collegno – via San Massimo - Certosa Binari Limite sede Ingombro totale 13 Collegno – Viale XXIV maggio Binari Limite sede Ingombro totale 14 Collegno – JF Kennedy Binari Limite sede Ingombro totale -

Allegato I - Residenti

ALLEGATO I - RESIDENTI Protocollo Zona Ovest di Torino Società dei Comuni di Alpignano, Buttigliera Alta, Collegno, Druento, Pianezza, Grugliasco, Rivoli, Rosta, San Gillio, Venaria Reale, Villarbasse Via Torino 9, presso Villa 7, Parco della Certosa – 10093 Collegno (TO) Richiesta per l’assegnazione di contributi per l’acquisto di biciclette e altri mezzi di mobilità sostenibile ad uso urbano – Azione “biciXtutti” - Progetto “Vi.VO: Via le Vetture dalla zona Ovest di torino” – Programma nazionale sperimentale per la mobilità sostenibile casa-scuola casa-lavoro finanziato dal Ministero dell'ambiente e della tutela del territorio e del mare Io (nome e cognome) __________________________________________________________________ nato/a a _____________________________________ prov. _________ il ________________________ residente a ____________________ in via ____________________________ civico n. ______________ domiciliata/o (indicare solo se diversa dalla residenza) a ____________________in via_______________________ civico n. _______ telefono ______________________________ cellulare n. ______________________ codice fiscale __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ indirizzo email________________________________________________________________________ indirizzo di PEC (posta elettronica certificata)________________________________________________ Dati Bancari Intestatario del c/c ___________________________________________________________________ Banca _____________________________________________________________________________ IBAN -

Alluvione Nel Torinese

LA CRONACA DEI DANNI NEL TORINESE Nel Torinese la situazione dei corsi d’acqua, già colmi a causa delle abbondanti precipitazioni dei giorni precedenti, si aggrava decisamente nelle prime ore di Giovedì 29 Maggio, quando si registrano i primi dissesti e allagamenti. Nella tarda mattinata la Dora Riparia esonda a Bussoleno; in Val di Susa e in Val Chisone molte strade e ponti vengono chiusi, in previsione dell’imminente ondata di piena, mentre proseguono incessantemente le precipitazioni. Nel primo pomeriggio, a Villarpellice, una frana si abbatte su un’abitazione provocando la morte di tre persone, tra cui una bambina di tre anni (i corpi verranno rinvenuti solamente dopo le lunghe ricerche dei soccorritori); nello stesso smottamento perde la vita un automobilista. Nel frattempo, a Torino tutti i ponti vengono presidiati dalla Protezione Civile e viene evacuato in via precauzionale l’ospedale Amedeo di Savoia; il Po allaga i locali pubblici dei Murazzi. Il Po ai Murazzi (Torino) giovedì pomeriggio: la piena deve ancora arrivare. Nel tardo pomeriggio pressoché tutti i corsi d’acqua del Torinese hanno superato i livelli di elevata criticità; in montagna continua a piovere, e le precipitazioni si estendono anche alle zone di pianura, finora rimaste ai margini, sotto forma di rovesci anche intensi. In Val Pellice 300 persone vengono evacuate dalle loro abitazioni; alcuni comuni, tra cui quello di Prali, risultano isolati. Col passare delle ore i fiumi e i torrenti che raccolgono l’acqua dalle montagne riversano il loro flusso nel Po, che inizia a crescere fino a sfiorare in più punti la piena straordinaria. -

Economic Inequality in Northwestern Italy: a Long-Term View (Fourteenth to Eighteenth Centuries)

Guido Alfani PAM - Bocconi University Dondena Centre and IGIER Via Roentgen 1, 20136 Milan - Italy [email protected] Economic inequality in northwestern Italy: a long-term view (fourteenth to eighteenth centuries) (provisional version – please ask for author’s consent to quote) 1 Abstract This article provides a comprehensive picture of economic inequality in northwestern Italy (Piedmont), focusing on the long-term developments occurred during 1300-1800 ca. Regional studies of this kind are rare, and none of them has as long a timescale. The new data proposed illuminate many little-known aspects of wealth distribution and general economic inequality in preindustrial times, and support the idea that during the Early Modern period, inequality grew everywhere: both in cities and in rural areas, and independently from whether the economy was growing or stagnating. This finding challenges earlier views that explained inequality growth as the consequence of economic development. The importance of demographic processes affecting inequality is underlined, and the impact of severe mortality crises, like the Black Death, is analyzed. Keywords Economic inequality; wealth concentration; middle ages; early modern period; Piedmont; Sabaudian States; Italy; plague; Black Death Acknowledgements The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC Grant agreement No. 283802, EINITE-Economic Inequality across Italy and Europe, 1300-1800. 2 The history of long-term trends in economic inequality is still largely to be written. After decades of research, mostly generated by Simon Kuznets' seminal 1955 article which introduced the notion that inequality would follow an inverted-U path through the industrialization process (the so-called ‘Kuznets curve’)1, we now have a good knowledge of the developments in inequality through the last couple of centuries, although only for selected countries like Britain, France, Italy, Spain, and the U.S. -

Itinerando Con I “Personaggi Risorgimentali”

CHIERI La vita di Don Bosco nei luoghi dove egli visse, studio’ e lavoro’ 10 anni. Centro visite Don Bosco, via S. Filippo ITINERANDO CON I Domenica 11 settembre dalle 15.00 alle 17.00 - a seguire: “PERSONAGGI RISORGIMENTALI” RIVA PRESSO CHIERI Scopri la Provincia attraverso i suoi personaggi storici vita di San Domenico Savio con visita e rappresentazione al Museo del Paesaggio sonoro a Palazzo. Possibilità di cena “Piemonte in tavola” presso il ristorante “Nazionale” a euro 20, su prenotazione. Il territorio provinciale verrà riscoperto attraverso i suoi personaggi storici. Domenica 11 settembre dalle 17.30 alle 19.00 Massimo d’ Azeglio, il Conte di Cavour, Don Bosco e molti altri attori del Risorgimento della nostra provincia a cui sono legati, spesso inaspettatamente, CAVOUR angoli riposti delle nostre città d’arte, interpretati da attori professionisti, * visita ai luoghi di Cavour da cui prende il nome il celebre Conte (la Rocca e il mulino) accompagneranno i visitatori e i turisti alla scoperta dei luoghi nascosti e * visita animata a Villa Giolitti aperta per l’occasione sconosciuti del territorio provinciale e della sua storia ottocentesca. * visita all’Abbazia di Santa Maria (chiesa e museo) Verranno riaperte per l’occasione ville private e castelli. * Gran finale con la rappresentazione teatrale e danzante “C’era una volta l’Italia che non c’era” a cura del gruppo storico Il programma si articola su domeniche e sabati pomeriggio tra aprile e ottobre “Nobilta’ Sabauda” di Rivoli con la visita dei luoghi dove sono nati o vissuti i personaggi del Risorgimento * Degustazione con prodotti tipici locali * Possibilità di cena con degustazione del “Cavour” (piatto risorgimentale e dei più bei siti di interesse turistico. -

Zona Naturale Di Salvaguardia Della Dora Riparia

Zona Naturale di Salvaguardia della Dora Riparia CONVENZIONE DI GESTIONE Rev 7 del 10/10/18 Art. 1 – Convenzione per la gestione associata della Zona naturale di Salvaguardia della Dora Riparia Ai sensi dell’art. 30, Testo Unico degli Enti Locali (D. Lgs. n. 267/2000), i Comuni di Almese, Alpignano, Avigliana, Buttigliera Alta, Caselette, Collegno, Pianezza, Rivoli e Rosta si convenzionano per la gestione associata della Zona naturale di Salvaguardia della Dora Riparia. E’ identificata quale Zona naturale di salvaguardia della Dora Riparia il territorio indicato con la sigla “z4” all’art. 52bis e perimetrato nelle Tavole nn. 75-78, alla scala 1:25.000 allegate al testo coordinato della Legge Regionale n. 19/2009, Testo unico sulla tutela delle aree naturali e della biodiversità. Art. 2 - Finalità e funzioni La Convenzione ha per scopo l’organizzazione della gestione amministrativa, tecnica, di pianificazione, promozione e valorizzazione della Zona naturale di salvaguardia individuata all’art. 1. In particolare, tramite la presente Convenzione, i Comuni sottoscrittori si propongono di organizzare la gestione associata della Zona naturale di salvaguardia. Scopi e finalità della gestione associata sono: Per seguire e garantire le finalità che hanno portato all’istituzione della Zona naturale di salvaguardia, così come indicate all’ art. 52ter della Legge Regionale n. 19/2009, Testo unico sulla tutela delle aree naturali e della biodiversità: a) tutelare gli ecosistemi agro-forestali esistenti; b) promuovere iniziative di recupero naturalistico -

Inpeco Site, Italy

Siemens Healthineers Global Training Center Inpeco site, Italy Training Location Inpeco S.p.A. Via Givoletto, 15 Val Della Torre (Turin) ITALY Andrea Nugnes Daniele Cascino Customer Care Team Leader Hardware Service Specialist Phone: +41 91 9118 208 Phone: +41 91 9118240 Phone: +39 011 7548208 Phone: +39 011 7548 240 e-Mail: [email protected] e-Mail: [email protected] Vald Hotel (5-minute drive from Inpeco) NH Lingotto (30-minute drive from Val Della Torre) Via Lanzo 35 Via Nizza 262 10040 Val della Torre (TO), Italy 10126 Turin, Italy Phone: +39 011 96 89 696 Phone: +39 011 6642000 Fax: +39 011.96.89.695 e-Mail: [email protected] e-Mail: [email protected]/ http://www.nh-hotels.com/ http://www.valdhotel.it/en Arrival by Airplane The closest Airport would be Torino Caselle (30 minutes’ drive from Val Della Torre), but also Milano Malpensa would work (90 minutes’ drive from Val Della Torre). Arrival by Public Transport If you arrive in Turin Airport (Caselle), the best way to travel to the Inpeco facility is a taxi (30 mins drive). If you arrive in Milan Airport (MXP or LIN) taxi is more expensive, but the solution by public transport a bit complicated: To reach the Inpeco facility by public transport is not that easy. If you arrive by plane, you have to take a shuttle to the Milan Centrale railway station (from MXP 1 hour, from LIN 20 min). From the Milan Centrale railway station you should take a train to Turin railway station (Porta Nuova or Porta Susa, 1 hour more or less) and then a taxi to Inpeco facility.