Oxford Heritage Walks Book 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Oxford Castle Perimeter Walk

Historic Oxford Castle 10 Plan (1878 Ordnance N Survey) and view of Perimeter Walk 9 11 12 the coal wharf from Bulwarks Lane, 7 under what is now Beat the bounds of Oxford Castle Nuffield College 8 1 7 2 4 3 6 5 Our new book Excavations at Oxford Castle 1999-2009 A number of the features described on our tour can be is available Oxford Castle & Prison recognised on Loggan’s 1675 map of Oxford. Note that gift shop and Oxbow: Loggan, like many early cartographers, drew his map https://www.oxbowbooks.com/ from the north, meaning it is upside-down compared to To find out more about Oxford modern maps. Archaeology and our current projects, visit our website or find us on Facebook, Twitter and Sketchfab: J.B. Malchair’s view of the motte in 1784 http://oxfordarchaeology.com @oatweet “There is much more to Oxford Castle than the mound and shops you see today. Take my tour to facebook.com/oxfordarchaeology ‘beats the bounds’ of this historic site sketchfab.com/oxford_archaeology and explore the outer limits of the castle, and see where excavations To see inside the medieval castle and later prison visit have given insights into the Oxford Castle & Prison: complex history of this site, that https://www.oxfordcastleandprison.co.uk/ has fascinated me for longer than I care to mention!” Julian Munby View towards the castle from the junction of New Road, 1911 2 Head of Buildings Archaeology Oxford Archaeology Castle Mill Stream Start at Oxford Castle & Prison. 1 8 The old Court House that looks like a N 1 Oxford Castle & Prison The castle mound (motte) and the ditch and Castle West Gate castle is near the site of the Shire Hall in the defences are the remains of the ‘motte and 2 New Road (west) king’s hall of the castle, where the justices bailey’ castle built in 1071 by Robert d’Oilly, 3 West Barbican met. -

1. 2012-05-09 Contents & 1St Part Existing Situation.Pub

Worcester College - Oxford Landscape Character Analysis Visual Impact Assessment Historic Garden Character Analysis An integrated report in support of a Planning Application for New Lecture Theatre New College Kitchen Alterations to Existing Buildings Report by Anne Keenan MA BEd(Hons) DipLA MSGD Landscape Architect & Garden Designer T. 01264 324192 E. [email protected] I. www.annekeenan.co.uk May 2012 Worcester College - Oxford CONTENTS Introduction Existing Situation Location Planning Context Physical Influences: Topography Geology & Soils Trees Ecology Landscape Classification & Features Human Influences: Historic Development Historic Assets Historic Landscape - Garden Character Areas Visual Survey of the Proposed Development Sites Kitchen Quad Pump Quad Landscape Summary The Proposal Kitchen Quad: The Proposed Buildings The Landscape Design Pump Quad: The Proposed Buildings The Landscape Design Impact of the Proposal Introduction Landscape Impacts Visual Impacts Heritage Assets & Impact Zone of Visual Impact Views to the Development Site/s Heritage Assets within Important Views Summary of Positive & Negative Impacts Mitigation/Enhancement Primary & Secondary Conclusion Worcester College - Oxford Introduction This document has been produced in support of a planning application for a new Lecture Theatre & College Kitchen, and existing building alterations, at Worcester College Oxford. The aims of the study are to: describe, classify and evaluate the landscape, specifically the townscape and the historic garden in the context of the proposal to identify the visual impact of the proposals to analyse any mitigation and enhancement measures to evaluate the overall landscape and visual impact of the proposed buildings. The assessment seeks to present a fully integrated view of the landscape incorporating all the features and attributes that contribute to the special and distinctive character of the site. -

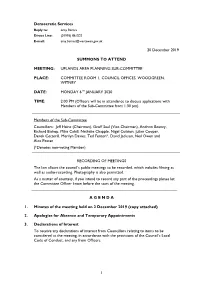

Uplands 06.01.2020

Democratic Services Reply to: Amy Barnes Direct Line: (01993) 861522 E-mail: [email protected] 20 December 2019 SUMMONS TO ATTEND MEETING: UPLANDS AREA PLANNING SUB-COMMITTEE PLACE: COMMITTEE ROOM 1, COUNCIL OFFICES, WOODGREEN, WITNEY DATE: MONDAY 6TH JANUARY 2020 TIME: 2.00 PM (Officers will be in attendance to discuss applications with Members of the Sub-Committee from 1:30 pm) Members of the Sub-Committee Councillors: Jeff Haine (Chairman), Geoff Saul (Vice-Chairman), Andrew Beaney, Richard Bishop, Mike Cahill, Nathalie Chapple, Nigel Colston, Julian Cooper, Derek Cotterill, Merilyn Davies, Ted Fenton*, David Jackson, Neil Owen and Alex Postan (*Denotes non-voting Member) RECORDING OF MEETINGS The law allows the council’s public meetings to be recorded, which includes filming as well as audio-recording. Photography is also permitted. As a matter of courtesy, if you intend to record any part of the proceedings please let the Committee Officer know before the start of the meeting. _________________________________________________________________ A G E N D A 1. Minutes of the meeting held on 2 December 2019 (copy attached) 2. Apologies for Absence and Temporary Appointments 3. Declarations of Interest To receive any declarations of interest from Councillors relating to items to be considered at the meeting, in accordance with the provisions of the Council’s Local Code of Conduct, and any from Officers. 1 4. Applications for Development (Report of the Business Manager – Development Management – schedule attached) Purpose: To consider applications for development, details of which are set out in the attached schedule. Recommendation: That the applications be determined in accordance with the recommendations of the Business Manager – Development Management. -

Living with New Developments in Jericho and Walton Manor

LIVING WITH NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN JERICHO AND WALTON MANOR A discussion paper examining the likely impacts upon the neighbourhood of forthcoming and expected developments Paul Cullen – November 2010 1. Introduction 2. Developments approved or planned 3. Likely effects of the developments 3.1 More people living in the area. 3.2 More people visiting the area daily 3.3 Effects of construction 4. Likely outcomes of more residents and more visitors 4.1 More activity in the neighbourhood every day 4.2 More demand for shops, eating, drinking and entertainment 4.3 More vehicles making deliveries and servicing visits to the area 4.4 More local parking demand 4.5 Demand for places at local schools will grow 5. Present day problems in the neighbourhood 5.1 The night-time economy – and litter 5.2 Transient resident population 5.3 Motor traffic congestion and air pollution 5.4 Narrow and obstructed footways 6. Wider issues of travel and access 6.1 Lack of bus links between the rail station and Woodstock Road 6.2 Lack of a convenient pedestrian/cycle link to the rail station and West End 6.3 The need for travel behaviour change 7. The need for a planning led response 7.1 Developer Contributions 7.2 How should developers contribute? 7.3 What are the emerging questions? 8. Next steps – a dialogue between the community, planners and developers 1 LIVING WITH NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN JERICHO AND WALTON MANOR A discussion paper examining the likely impacts upon the neighbourhood of forthcoming and expected developments 1. Introduction Many new developments are planned or proposed in or near Jericho and these will have a substantial impact on the local community. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Samuel Lipscomb Seckham

Samuel Lipscomb Seckham By PETER HOWELL l TIL recently the name of Samuel Lipscomb Seckham was fairly widely U known in Oxford as that of the architect of Park Town. A few other facts, such as that he was City Surveyor, were known to the cognoscenti. No-one, however, had been able to discover anything significant about his background, let alone what happened to him after he built the Oxford Corn Exchange in 1861-2. In '970 a fortunate chance led to the establishment of contact with Dr. Ann Silver, a great-granddaughter of Seckham, and as a result it has been po ible to piece together the outline ofhis varied career.' He was born on 25 October ,827,' He took his names from his grandparents, Samuel Seckham (1761-1820) and Susan Lipscomb (d. 18'5 aged 48).3 His father, William ('797-,859), kept livery stables at 20 Magdalen Street, Oxford,. and prospered sufficiently to retire and farm at Kidlington.5 The family came from Devon, where it is aid that Seccombes have occupied Seccombe Farm at Germans week, near Okehampton, since Saxon limes. Seccombes are still living there, farming. It is thought that Seckllam is the earlier spelling, but tombstones at Germansweek show several different versions. 6 It is not known how the family reached Oxford, but Samuel Lipscomb Seckham's great-grandmother Elizabeth was buried at St. Mary Magdalen in 1805.7 His mother was Harriett Wickens (1800-1859). Her grandfather and father were both called James, which makes it difficult to sort out which is which among the various James W;ckens' recorded in I The fortunate chance occurred when Mrs. -

THE MUSEUM During 1970 and 1971 Considerable Work Has Been Done on the Collections, Although Much Still Remains to Be Sorted Out

THE MUSEUM During 1970 and 1971 considerable work has been done on the collections, although much still remains to be sorted out. The work of identifying and labelling geological specimens has been completed, and the insect collections sorted, fumi- gated, labelled, put in checklist order and card indexed. The egg collection has also been re-labelled and card indexed, and some specimens added to it. In the historical field a large collection of photographic plates, mainly taken by Taunt of Oxford about 1900, has been sorted and placed in individual envelopes. Racking has been installed in part of the first floor of the stable and most of the collection of pottery sherds transferred to it, where it is easily accessible. A start has been made on the production of a card index of the folk collection and to-date some 1,500 cards have been completed. At short notice reports on archaeological sites in the Chilterns and in the River Ouse Green Belt were prepared, and at greater leisure one on the Vale of Aylesbury for the County Planning Department. This involved visiting a very large number of sites, which did however yield additional information about some. A start has been made on an examination of air photographs of the county, and a number of new sites, particularly of ring ditches and medieval sites, have been found. Excavations were carried out by the museum staff on four sites referred to in The Records, three of them on behalf of the Milton Keynes Research Committee. Amongst the exhibitions was one of Museum Purchases 1960-1970, opened by Earl Howe, Chairman of the County Education Committee, which showed all the purchases made during that period. -

NORTH OXFORD VICTORIAN SUBURB CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Consultation Draft - January 2017

NORTH OXFORD VICTORIAN SUBURB CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Consultation Draft - January 2017 249 250 CONTENTS SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANCE 5 Reason for appraisal 7 Location 9 Topography and geology 9 Designation and boundaries 9 Archaeology 10 Historical development 12 Spatial Analysis 15 Special features of the area 16 Views 16 Building types 16 University colleges 19 Boundary treatments 22 Building styles, materials and colours 23 Listed buildings 25 Significant non-listed buildings 30 Listed parks and gardens 33 Summary 33 Character areas 34 Norham Manor 34 Park Town 36 Bardwell Estate 38 Kingston Road 40 St Margaret’s 42 251 Banbury Road 44 North Parade 46 Lathbury and Staverton Roads 49 Opportunities for enhancement and change 51 Designation 51 Protection for unlisted buildings 51 Improvements in the Public Domain 52 Development Management 52 Non-residential use and institutionalisation large houses 52 SOURCES 53 APPENDICES 54 APPENDIX A: MAP INDICATING CHARACTER AREAS 54 APPENDIX B: LISTED BUILDINGS 55 APPENDIX C: LOCALLY SIGNIFICANT BUILDINGS 59 252 North Oxford Victorian Suburb Conservation Area SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANCE This Conservations Area’s primary significance derives from its character as a distinct area, imposed in part by topography as well as by land ownership from the 16th century into the 20th century. At a time when Oxford needed to expand out of its historic core centred around the castle, the medieval streets and the major colleges, these two factors enabled the area to be laid out as a planned suburb as lands associated with medieval manors were made available. This gives the whole area homogeneity as a residential suburb. -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner -

Peter Smith, 'Lady Oxford's Alterations at Welbeck Abbey 1741–55', the Georgian Group Journal, Vol. Xi, 2001, Pp

Peter Smith, ‘Lady Oxford’s alterations at Welbeck Abbey 1741–55’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XI, 2001, pp. 133–168 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2001 LADY OXFORD’S ALTERATIONS AT WELBECK ABBEY, – PETER SMITH idowhood could be a rare time of indepen - On July the Duke died unexpectedly, after Wdence for a woman in the eighteenth century, a riding accident at Welbeck, precipitating a and especially for one like the dowager Countess of mammoth legal battle over the Cavendish estates. By Oxford and Mortimer (Fig. ), who had complete his will all his estates in Yorkshire, Staffordshire and control of her own money and estates. Born Lady Northumberland were bequeathed to his year-old Henrietta Cavendish-Holles in , the only daughter Henrietta, while an estate at Orton in daughter of John Holles, st Duke of Newcastle, and Huntingdonshire passed to his wife and the remainder his wife, formerly Lady Margaret Cavendish, she of his considerable property passed to his nephew chose to spend her widowhood building, like her Thomas Pelham. This would have meant that the great-great-great-grandmother, Bess of Hardwick, former Cavendish estates in Nottinghamshire and before her. Derbyshire would have gone to Thomas Pelham, not Lady Oxford had fought hard, and paid a high Henrietta. When the widowed Duchess discovered price, to retain her mother’s Cavendish family estates, the terms of her husband’s will she ‘was indignant and she obviously felt a particularly strong beyond measure’ and ‘immediately resolved to attachment to them. These estates were centred dispute its validity’. The legal battle which ensued around the former Premonstratensian abbey at was bitter and complex, and it was only finally settled Welbeck, in Nottinghamshire, but also included the after the death of the Duchess by a private Act of Bolsover Castle estate in Derbyshire and the Ogle Parliament in . -

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 3

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 3 On foot from Catte Street to Parson’s Pleasure by Malcolm Graham © Oxford Preservation Trust, 2015 This is a fully referenced text of the book, illustrated by Edith Gollnast with cartography by Alun Jones, which was first published in 2015. Also included are a further reading list and a list of common abbreviations used in the footnotes. The published book is available from Oxford Preservation Trust, 10 Turn Again Lane, Oxford, OX1 1QL – tel 01865 242918 Contents: Catte Street to Holywell Street 1 – 8 Holywell Street to Mansfield Road 8 – 13 University Museum and Science Area 14 – 18 Parson’s Pleasure to St Cross Road 18 - 26 Longwall Street to Catte Street 26 – 36 Abbreviations 36 Further Reading 36 - 38 Chapter 1 – Catte Street to Holywell Street The walk starts – and finishes – at the junction of Catte Street and New College Lane, in what is now the heart of the University. From here, you can enjoy views of the Bodleian Library's Schools Quadrangle (1613–24), the Sheldonian Theatre (1663–9, Christopher Wren) and the Clarendon Building (1711–15, Nicholas Hawksmoor).1 Notice also the listed red K6 phone box in the shadow of the Schools Quad.2 Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, architect of the nearby Weston Library, was responsible for this English design icon in the 1930s. Hertford College occupies the east side of Catte Street at this point, having incorporated the older buildings of Magdalen Hall (1820–2, E.W. Garbett) and created a North Quad beyond New College Lane (1903–31, T.G. -

The Gothick COMMONWEALTH of AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969

702132/702835 European Architecture B the Gothick COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice the Gothick a national style a style with genuine associational values a style for which there was local archaeological evidence a style with links to real architecture THETHE EARLYEARLY GOTHICKGOTHICK Woodstock Manor, Oxfordshire, illustrated in 1714 J D Hunt & Peter Willis [eds], The Genius of the Place (London 1975), p 119 The Belvedere, Claremont, Esher, Surrey, by Vanbrugh, c 1715-16; Vanbrugh Castle, Greenwich, by Vanbrugh, 1717 George Mott & S S Aall, Follies and Pleasure Pavilions (London 1989), p 46; Miles Lewis King Alfred's Hall, Cirencester Park, begun 1721, contemporary & modern views Christopher Hussey, English Gardens and Landscapes (London 1967), pl 93 mock Fort at Wentworth Castle, begun 1728 Vilet's engraving of 1771 & modern photo of the remains Country Life, 14 February 1974, p 309 the 'Temple' at Aske, Yorkshire, apparently by William Kent, built by William Halfpenny between 1727 and 1758: view & ceiling of the principal room in the Octagon Tower Mott & Aall, Follies and Pleasure Pavilions, p 29; Country Life, 26 September 1974,