Volume 10, Fall 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSI5*-WA Coruña

CSI5*-W A Coruña 13th - 15th(ESP) December 2019 Casas Novas Equestrian Centre 02 TROFEO ESTRELLA GALICIA CSI2* - Int. jumping competition in two phases Table A, FEI Art. 274.1.5.3 Height: 1.40 m Begin: Friday, 13.12.2019 - 15.15 hrs O F F I C I A L R E S U L T Rk CNR Horse Rider Nation Result 1. 101 Llain de Llamosas Jesus Garmendia Echevarria ESP 0 penalties 24.05 sec bay / 8y / G / 105PI37 / Colomer Barrera,Francisco 2.310,00 EUR phase 2 2. 124 Coltaire Jacobo Fontan Garcia ESP 0 penalties 24.29 sec bay / 9y / G / ISH / 105LL19 / Sergio Valdemar Freitas F. Sousa / Marion Hughes 1.400,00 EUR phase 2 3. 129 Balasco de l'Abbaye Pedro Fernando Mateos Rodriguez ESP 0 penalties 24.69 sec chest / 8y / G / Ugano Sitte / Le Tot de Semilly / SF / 105IU66 / Miguel Angel GIL / Louis Leconte 1.050,00 EUR phase 2 4. 103 AD Amigo B Gonzalo Añon Suarez ESP 0 penalties 24.77 sec bay / 14y / S / Tadmus / Heartbreaker / KWPN / 103AX27 / Añon Team Horses S.L. / MTS.G. En G.F. Brinkman,Zutphen (ne 700,00 EUR phase 2 5. 176 Dento Bernardo Ladeira POR 0 penalties 25.05 sec grey / 11y / S / Cardento / Iroko / KWPN / 103QM30 / Bl Horses,Lda / A.F. Oude Nijeweme,Haarle (ned) 420,00 EUR phase 2 6. 170 Tornado v. Teresa Blazquez - Abascal ESP 0 penalties 25.18 sec bay / 8y / G / Toulon / Contender / HOLST / 105JJ47 / Yeguada Valbanera S.L. / Schockemöhle,Vanessa 315,00 EUR phase 2 7. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

2017 PENNSYLVANIA NATIONAL HORSE SHOW Ryegate Show Services Inc

Ryegate Show Services Inc. Jump Order 2017 PENNSYLVANIA NATIONAL HORSE SHOW Class: 57 DONNA RICHARDSON EQUITATION TRAINING SESSIO Ring:DAYTIME Order HH:MM:SS Entry Fnc Hgt Horse Owner Rider Trainer 1 854 HEROY VON DE HEI Gochman Sport Horse Llc Mimi Gochman Stacia Madden 2 1263 NOBEL PRIZE Emma Crate Ellyn Fritz Kristy Herrera 3 772 NICE AS TWICE Caroline Michele Dugas Caroline Michele Timothy Maddrix Dugas 4 817 BRASS VERDICT Fallon O'Connell Fallon O'Connell Kathryn Johnson 5 485 CABIDO Phoebe Alwine Phoebe Alwine Jane Fennessy 6 456 COURAGE Abigail Lefkowitz Abigail Lefkowitz Audrey Feldman 7 775 NEWSFLASH 3E Madigan Eppink Madigan Eppink Laura Nicholson 8 933 CAPTAIN JACK Clear Ride Llc Emma Ellis John Brennan 9 566 UPCHARGE Ashland Farms Addison Howe Bradley Spragg 10 600 BRECKENRIDGE Ashland Farms Grady Lyman Emily Smith 11 769 GENTLEMEN Madison Mitchell Madison Mitchell Heather Irvine 12 1188 CLOONEY Sophia Davies Sophia Davies Alison Penn Sherred 13 1025 CAPTAIN DARCO Allyson Blais Lindsey Klein Alan Korotkin HELDENLAAN Z 14 1251 REVELRY Mad Season, Llc Caroline Bald Valerie Renihan 15 482 CONSANTO Adelaide Toensing Adelaide Toensing Kristi Smith 16 1091 QUANTICO Bay Noland-Armstrong Bay Shannon Meehan Noland-Armstrong 17 974 VONDEL DH Z Maarten Huygens Billi Rose Brandner Valerie Renihan 18 644 CHILLAVERT Charlotte Novy Llc Charlotte Novy Lynn Jayne 19 856 TRUMPET Gochman Sport Horse Llc Alexa Schwartz Stacia Madden 20 1240 CARNEROS NV Ransome Rombauer Camille Leblond Alexis Taylor-Silvernale 21 696 GOT MILK Britta Stoeckel Britta Stoeckel Joanne Kurinsky 22 1053 ELI Coleman Holland Coleman Holland Andrea Guzinski 23 1260 CARUSO Ravi Singh Katie Ray Dominique Damico 24 1030 COOLEY NOTHING Kyle Carter Chloe White Amanda Lyerly BETTER B 25 784 ZERSINA Annabella Sanchez Kennedy Mccaulley Alex Jayne 26 1031 LET IT GO Isabelle Song Isabelle Song Robert Braswell 27 674 CORETTA Suzanna Treske Morgan Tabler Ann Garnett Wheeler 28 1111 L.A. -

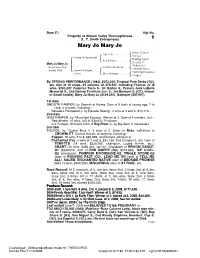

Fttdec2008cat.Pdf

Barn E1 Hip No. Property of Hidden Valley Thoroughbreds (L. T. Smith Enterprises) 1 Mary Jo Mary Jo Native Dancer Jig Time . { Kanace Strong Performance . Blazing Count { Extra Alarm . { Deedee O. Mary Jo Mary Jo . *Noholme II Gray/roan mare; Smooth At Holme . { *Smooth Water foaled 1993 {Smooth Pamper . *Moonlight Express (1981) { Miss Pamper . { Poupee By STRONG PERFORMANCE (1983), $252,040, Tropical Park Derby [G2], etc. Sire of 15 crops, 35 winners, $1,375,507, including Thomas Jo (8 wins, $390,207, Federico Tesio S., Sir Barton S., Francis Jock LaBelle Memorial S., 2nd Gallery Furniture Juv. S., 3rd Belmont S. [G1]; winner in Saudi Arabia), Mary Jo Mary Jo ($169,240), Quitaque ($97,907). 1st dam SMOOTH PAMPER, by Smooth at Holme. Dam of 9 foals of racing age, 7 to race, 4 winners, including-- Nevada’s Pampered (f. by Nevada Reality). 3 wins at 3 and 4, $10,713. 2nd dam MISS PAMPER, by *Moonlight Express. Winner at 3. Dam of 4 winners, incl.-- Redskinette. 10 wins, 3 to 6, $30,052. Producer. Jr’s Pamper. Unraced. Dam of Big River (c. by Big Gun) in Venezuela. 3rd dam POUPEE, by *Quatre Bras II. 3 wins at 2. Sister to Bras, half-sister to CROWNLET. Dam of 9 foals, all winners, including-- Puppet. 18 wins, 2 to 8, $56,895, 3rd Richard Johnson S. Enchanted Eve. 4 wins at 2 and 3, $32,230, 2nd Comely H., etc. Dam of TEMPTED (18 wins, $330,760, champion, Ladies H.-nAr, etc.), SMART (19 wins, $365,244, set ntr). Granddam of BROOM DANCE- G1 ($330,022, dam of END SWEEP [G3], $372,563), ICE COOL- G2 (champion), PUMPKIN MOONSHINE-G2; TINGLE STONE-G3 (dam of ROUSING PAST [G3]), LEAD ME ON (dam of TELL ME ALL), SALEM, ENCHANTED NATIVE (dam of BEDSIDE PROMISE [G1] 14 wins, $950,205), MISGIVINGS (dam of AT RISK), etc. -

The Most Renowned Equestrian Magazine in the Middle East

L I S B H E U D P S & I N D C E E 40 D 1 N 9 U 9 O 7 F W inter 2012 THE MOST RENOWNED EQUESTRIAN MAGAZINE IN THE MIDDLE EAST VIEW POINT FROM THE CHAIRMAN kick off our content with culture, judges with plenty of background ‘The Horse: From Arabia To Royal and experience under their wings: Ascot’, in which we showcase a Jordan’s Ali Al Sharif and Egypt’s remarkable exhibit which was put on Dr. Abu Bakr Hashem. Reading their by the British Museum this summer views, you realise that, for these two tracing the evolution of the Arabian judges, show jumping is not just a horse from the desert to the famous sport, but truly a passion. We round race courses of Britain. The exhibit out the issue with our alternative included many extraordinary ancient therapy, training and medical advice and modern artefacts depicting this columns with Lady Coleen Heller’s evolution, some of which we present narrative account of her horse here. healing experiences, technical training tips on how to better develop We continue with two amazing role riding skills through balance, models of persistence, commitment understanding and communication, and patience: 71 year old Olympian and Dr. Oz’s medical article on how Hiroshi Hoketsu representing Japan to investigate poor performance with in London 2012 for the 4th time, and field exercise testing. France’s Alexandra Ledermann in a wide-ranging interview where we Finally, we are very proud to say learn about her true character and we have completed and published ambitions. -

2017 Selected Yearling Sale Catalog Corrections

2017 SELECTED YEARLING SALE CATALOG CORRECTIONS & UPDATES FIRST SESSION Tuesday, October 3, 2017 Hip # 1 SOUTHPORT BEACH (Somebeachsomewhere - Benear) 1st Dam BENEAR LIMELIGHT BEACH 22 wins $1,288,319 MANHATTAN BEACH 8 wins $633,014 Third in Hoosier Park Pacing Derby 09/22/2017 Hip # 2 WALKING TRAIL (Western Ideal - Walk Softly) 1st Dam WALK SOFTLY SOFT IDEA 11 wins $383,713 Better Watch Out $10,546 2nd Dam TOYLEE HANOVER Producers: BINIONS (dam of GIANT SLAYER $101,676), Radar Tracking (grandam of MR HAM SANDWICH $149,872, ARTNERS IN CRIME $112,099) Hip # 3 RISEN DEO (Somebeachsomewhere - Worldly Beauty) 1st Dam WORLDLY BEAUTY ROCK N' ROLL WORLD $690,352 Third in Dan Patch Inv. 08/11/2017 at Hoosier 2nd Dam WORLD ORDER Producers: WORLDLY TREASURE (dam of *ODDS ON STEPHANIE p,2,Q1:57.3), ENCHANTED BEAUTY (dam of BETTORIFFIC $121,923), LOVELY LADY (dam of *SERIOUSLY GOOD p,3,1:56.1f), In Every Way (grandam of ROCK ICON $277,489, ROCK OUT $256,543, IVORY COLLECTION $126,544), Outtathisworld (dam of BEYOND DELIGHT $347,926) 3rd Dam RODINE HANOVER Producers: WESTERN CITY (dam of TERLINGUA $255,322, PASSPORT TO ART p,3,1:52.2; grandam of STIRLING ENSIGN p,4,1:52.4), ROMANTICIZE (dam of ROMANASCAPE $144,751; grandam of SHADOWBRIAND $246,889, KB'S BAD BOY $111,496, *ITS A GREAT WHITE p,2,1:59.1f), PERFECT PROFILE (grandam of COOPERSTOWN $497,996, TRUE REFLECTION $222,161, LUCKY DAY $123,108) Hip # 4 CAPTAIN'S PLAY (Captaintreacherous - Full Picture) 2nd Dam HEATHER'S WESTERN SOMEPLACE SPECIAL 23 wins $193,162 DRAMATIC POINT p,2,1:54.3 1 win $8,315 3rd Dam SANTASTIC JUMPIN JAKE FLASH 6 wins $43,701 PREACHER OLLIE $12,733 Third in The Standardbred S. -

Time Regained Proust, Marcel (Translator: Stephen Hudson)

Time Regained Proust, Marcel (Translator: Stephen Hudson) Published: 1931 Type(s): Novels, Romance Source: http://gutenberg.net.au 1 About Proust: Proust was born in Auteuil (the southern sector of Paris's then-rustic 16th arrondissement) at the home of his great-uncle, two months after the Treaty of Frankfurt formally ended the Franco-Prussian War. His birth took place during the violence that surrounded the suppression of the Paris Commune, and his childhood corresponds with the consolida- tion of the French Third Republic. Much of Remembrance of Things Past concerns the vast changes, most particularly the decline of the aristo- cracy and the rise of the middle classes, that occurred in France during the Third Republic and the fin de siècle. Proust's father, Achille Adrien Proust, was a famous doctor and epidemiologist, responsible for study- ing and attempting to remedy the causes and movements of cholera through Europe and Asia; he was the author of many articles and books on medicine and hygiene. Proust's mother, Jeanne Clémence Weil, was the daughter of a rich and cultured Jewish family. Her father was a banker. She was highly literate and well-read. Her letters demonstrate a well-developed sense of humour, and her command of English was suf- ficient for her to provide the necessary impetus to her son's later at- tempts to translate John Ruskin. By the age of nine, Proust had had his first serious asthma attack, and thereafter he was considered by himself, his family and his friends as a sickly child. Proust spent long holidays in the village of Illiers. -

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Name,Year Foaled Sire Dam Barn 5 Property of Adena Springs Broodmares 1445 ch. m. Siphonette, 2001 Siphon (BRZ) Peaceable Mood 1461 gr/ro. m. Stick N Stein, 1998 Darn That Alarm Salem Fires 1470 b. m. Sweet Tart, 2004 Lemon Drop Kid Willa Joe (IRE) 1478 dk. b./br. m. Thrill Time, 2006 Running Stag Awesome Thrill 1495 b. m. Wedded Woman, 2003 Siphon (BRZ) Erinyes 1504 b. m. Wilderness Call, 2001 Roy Forest Song 1514 dk. b./br. m. All Enchanting, 2005 Cherokee Run Glory High 1516 dk. b./br. m. Angel Dancer, 2001 Incurable Optimist Cotuit Bay 1548 gr/ro. m. Dancing Cherokee, 2004 Yonaguska Dancapade 1567 b. m. Elle, 1999 Mr. Prospector Calendar Lady 1582 gr/ro. m. Five by Five, 2004 Forestry Erin Moor 1603 dk. b./br. m. Good Fun, 2006 Awesome Again Miss Joker 1606 gr/ro. m. Graciously Soft, 2005 Vindication Siberian Fur 1642 b. m. Lonesome Lady, 2005 Running Stag Racey Lady 1656 ch. m. Maria Clarissa, 2001 Maria's Mon Cypherin Sally Barn 9 Property of Ann Marie Farm Broodmares 1448 b. m. Sky Blue Girl (GB), 1998 Sabrehill Nemea 1533 ch. m. Brazen Beauty, 1997 Lord At War (ARG) Secret Squaw Yearling 1449 b. f. unnamed, 2009 Kafwain Sky Blue Girl (GB) Barn 4 Consigned by Baccari Bloodstock LLC, Agent I Yearlings 1440 gr/ro. c. unnamed, 2009 Macho Uno Shesarealdoll 1502 ch. f. unnamed, 2009 With Distinction Wholelotofimage 1522 gr/ro. f. unnamed, 2009 Senor Swinger A Wonder She Is 1628 dk. -

WBFSH WORLD RANKING LIST - BREEDERS of JUMPING HORSES Ranking : 30/04/2021 (Included Validated FEI Results from 01/10/2020 to 30/04/2021)

WBFSH WORLD RANKING LIST - BREEDERS OF JUMPING HORSES Ranking : 30/04/2021 (included validated FEI results from 01/10/2020 to 30/04/2021) RANK BREEDER Points CURRENT NAME / BIRTH NAME FEI ID BIRTH YEAR GENDER STUDBOOK SIRE DAM SIRE 1 BELLEMANS JONAS 977 SCUDERIA 1918 TOBAGO Z / TOBAGO Z (ET) 104CT05 2008 STALLION ZANG TANGELO VD ZUUTHOEVE MR BLUE 2 BLANCKAERT, PATRICK & LAURENCE 655 OAK GROVE'S ENKIDU / BOHYSRA D'AUZAY LA 105TT17 2011 STALLION SF ENSOR VDH PLEVILLE QUIDAM DE REVEL 3 GESTÜT LEWITZ 645 CHACENDRA / CHACENDRA 104YQ51 2009 MARE MECKL CHACCO-BLUE CENTO 4 LAURENT BAILLET 60750 CHOISY AU BAC (FRA) 635 UNICK DU FRANCPORT / UNICK DU FRANCPORT 105AL54 2008 GELDING SF ZANDOR HELIOS DE LA COUR II 5 KARL HEINZ GIERKES 602 DICAS / DICAS 105AR59 2009 GELDING RHEIN DIARADO CASSINI I 6 M. FRANCOIS NIGER,M. PATRICK RABOT, ST RIVOAL (FRA) 590 TOLEDE DE MESCAM HARCOUR / TOLEDE DE MESCAM 104IY75 2007 MARE SF MYLORD CARTHAGO*HN KOUGLOF II 7 KIPP, WOLFGANG 585 CHECKER 47 / CHECKER 47 104YP79 2010 GELDING WESTF COMME IL FAUT 5 COME ON 8 LOTHAR WANNER 575 BALOU RUBIN R / BALOU RUBIN R 104DT17 2007 GELDING OS BALOU DU ROUET COULEUR-RUBIN 9 GEFFKEN, JÜRGEN 560 COBY 8 / COBY 8 105HZ25 2010 GELDING HANN CONTAGIO ESCUDO 19 10 RICARDO ROMERO 558 UNION DE LA NUTRIA / UNION DE LA NUTRIA 104YX41 2008 GELDING SF DIAMANT DE SEMILLY KANNAN 11 S.A.R.L. HARAS DES M 546 ANTIDOTE DE MARS / ANTIDOTE DE MARS 105IM15 2010 STALLION SF DIAMANT DE SEMILLY JARNAC 12 IVAN VAN HOECKE, EVERGEM (BEL) 520 HESTER / FRUEHLING VAN D'AVRIJE 103SD87 2005 GELDING BWP WANDOR VAN DE MISPELAERE PALESTRO VD BEGIJNAKKER 13 J. -

Bay Filly; Cox’S Ridge

Barn 14A-B Hip No. Consigned by Legacy Bloodstock, Agent XI 1 Western Sweep Gone West . Mr. Prospector Western Expression . {Secrettame {Tricky Game . Majestic Light Western Sweep . {Con Game Bay mare; End Sweep . Forty Niner foaled 2004 {Andover Sweep . {Broom Dance (1996) {Andover Square . Known Fact {Andover Cottage By WESTERN EXPRESSION (1996), $140,114, 2nd Carter H. [G1]. Sire of 11 crops, 168 winners, $11,817,664, including black type winners I Lost My Choo (7 wins, $442,740, Virginia Oaks [G3], Honey Fox S. [G3], etc.), Stunt Man (7 wins, $410,640, Don Rickles S., etc.), Artistic Express (4 wins, $251,034), Thunderestimate (4 wins, $183,144, Cab Calloway S.). 1st dam ANDOVER SWEEP, by End Sweep. 2 wins at 3, $55,398. Dam of 8 foals of racing age, 7 to race, 4 winners, including-- OLDE GLAMOUR (f. by Kelly Kip). 5 wins at 3 and 4, $190,599, Jersey Girl S.-R (BEL, $39,870), 2nd Deceit S. (BEL, $13,340). Western Sweep (f. by Western Expression). Black type-placed wnr, below. 2nd dam ANDOVER SQUARE, by Known Fact. 3 wins, $44,814. Dam of 7 winners, incl.-- Appealing Andover. 2 wins, $61,175. Dam of 5 winners, including-- MEGAN’S APPEAL (f. by Gold Case). Winner at 2, $127,004, Shady Well S.-R (WO, $98,730-CAN). Producer. 3rd dam ANDOVER COTTAGE, by Affiliate. Winner at 3. Dam of 5 winners, including-- WELL AWARE. 8 wins, $165,182, Fort Snelling S. (CBY, $9,175), etc. SAXON COTTAGE. Winner at 2 and 3, 24,577 euro in Ireland, Ballysax S., 2nd 2000 Guineas Trial, 3rd Anglesey S. -

2008 International List of Protected Names

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities _________________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Avril / April 2008 Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Derby, Oaks, Saint Leger (Irlande/Ireland) Premio Regina Elena, Premio Parioli, Derby Italiano, Oaks (Italie/Italia) -

2009 International List of Protected Names

Liste Internationale des Noms Protégés LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities __________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] 2 03/02/2009 International List of Protected Names Internet : www.IFHAonline.org 3 03/02/2009 Liste Internationale des Noms Protégés La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas,