Poultry Based Livelihoods of Rural Poor: Case of Kuroiler in West Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FAMILY POULTRY DEVELOPMENT Working Paper Issues, Opportunitiesandconstraints FAO ANIMALPRODUCTIONANDHEALTH 12

12 ISSN 2221-8793 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH working paper FAMILY POULTRY DEVELOPMENT Issues, opportunities and constraints Cover photographs Left image: ©Brigitte Bagnol Centre image: ©IFAD/Antonio Rota Right image: ©FAO/Olaf Thieme 12 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH working paper FAMILY POULTRY DEVELOPMENT Issues, opportunities and constraints Authors Olaf Thieme, Emmanuel Babafunso Sonaiya, Antonio Rota, Robyn G. Alders, Mohammad Abdul Saleque and Giacomo De’ Besi FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2014 Recommended Citation FAO. 2014. Family poultry development − Issues, opportunities and constraints. Animal Production and Health Working Paper. No. 12. Rome. Authors Olaf Thieme Livestock Production Systems Branch, Animal Production and Health Division, FAO, Rome, Italy [email protected] Emmanuel Babafunso Sonaiya Department of Animal Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria [email protected] Antonio Rota Policy and Technical Advisory Division (PTA), IFAD, Rome, Italy [email protected] Robyn G. Alders International Rural Poultry Centre (IRPC) of the KYEEMA Foundation, Australia; and Charles Perkins Centre and Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney, Australia [email protected] [email protected] Mohammad Abdul Saleque BRAC International, BRAC Centre, Dhaka, Bangladesh [email protected] Giacomo De’ Besi Private consultant [email protected] The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Poultry As a Development Tool

PART 3 Poultry as a Development Tool 503 Poultry production for livelihood improvement and poverty alleviation Frands Dolberg University of Århus, Denmark SUMMARY Millennium Development Goal Number One is to halve the number of poor people in the world by 2015. The present paper contains a discussion, based on the livelihoods frame- work, of how and under what conditions small poultry units can contribute to the achieve- ment of this and other Millennium Development Goals. The paper presents the livelihoods framework along with its micro- and macro-level features. Subsequently, it discusses the role of poultry in asset creation and as an entry point to improved livelihoods. A series of cases are presented: from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Swaziland, which illustrate various arguments related to the use of poultry for livelihood improvement and poverty alleviation. Strategies that use poultry production for livelihood improvement and poverty alleviation will be most relevantly applied in the countries where it has been most difficult to get development moving. These countries are variously described by development agencies as low-income countries under stress (LICUS), highly indebted poor countries (HIPC), low-income food deficit countries (LIFDCs), or countries that are placed low on the UN Human Development Index. The smallholder poultry approach is biased towards poor women; one estimate is that it is relevant for 160 million women and their families. However, it will not be easy to reach these potential beneficiaries, as bad governance and weak institutions characterize many of the countries where they live. Against this background, it is concluded that international organizations and networks have a particularly important role to play as storehouses of knowledge and technical expertise. -

Efficacy of in Ovo Delivered Prebiotics on Growth Performance, Meat Quality and Gut Health of Kuroiler Chickens in the Face of A

animals Article Efficacy of In Ovo Delivered Prebiotics on Growth Performance, Meat Quality and Gut Health of Kuroiler Chickens in the Face of a Natural Coccidiosis Challenge Harriet Angwech 1,2,*, Siria Tavaniello 1, Acaye Ongwech 1,2, Archileo N. Kaaya 3 and Giuseppe Maiorano 1 1 Department of Agricultural, Environmental and Food Sciences, University of Molise, 86100 Campobasso, Italy; [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (A.O.); [email protected] (G.M.) 2 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Gulu University, P.O. Box 166 Gulu, Uganda 3 School of Food Technology, Nutrition and Bio-engineering, Makerere University, P.O. Box 7062 Kampala, Uganda; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 August 2019; Accepted: 29 September 2019; Published: 28 October 2019 Simple Summary: The management of coccidiosis in poultry farms is mainly dependent on the use of anticoccidial drugs. Development of resistance to existing anticoccidial drugs coupled with restrictive use of antibiotics to control secondary bacterial infections following the ban on antibiotics, stresses the urgent need to explore alternative strategies for maintaining intestinal functionality in chickens for improved productivity. Prebiotics have been proposed as a solution to the intestinal problems of poultry. This study demonstrates that in ovo delivered prebiotics with or without antibiotics reduces severity of intestinal lesions and oocyst excretion induced by natural infection with Eimeria. Prebiotics protected Kuroiler chickens from coccidia in particular in the first 56 days of age and tended to have a synergistic effect with anticoccidial drug in the management of the disease post-infection in the field, with positive effects on performance and meat quality. -

Decision Tools for Family Poultry Development Rural, Urban and Peri-Urban Areas of Developing Countries

16 16 ISSN 1810-0708 FAO ANIMAL PRODUCTION AND HEALTH Family poultry encompasses all small-scale poultry production systems found in Decision tools for family poultry development rural, urban and peri-urban areas of developing countries. Rather than defining the production systems per se, the term is used to describe poultry production practised by individual families as a means of obtaining food security, income and gainful employment. Family poultry production is often perceived as an activity that can easily and quickly generate income and support food security for resource-poor households. However, the essential requirements for the efficient production of healthy and profitable poultry and eggs are frequently inadequately understood by those designing projects for resource-poor settings. This publication provides guidance for personnel in governments, development organizations and NGOs to better determine and plan development interventions for family poultry. guidelines The decision tools address the situation of four distinct family poultry production systems and their development opportunities: small extensive scavenging, extensive scavenging, semi-intensive production and small-scale intensive production. They describe the poultry production systems, including their required inputs and expected outputs and the techniques and tools used to assess the operational environment, in order to design interventions suited to the local conditions. Practical technical information are provided about genetics and reproduction, feeds and feeding, -

Epidemiology of Important Poultry Diseases in Nepal

Nepalese Vet. J. 36: 08 –14 Epidemiology of Important Poultry Diseases in Nepal T. R. Gompo*,1, U. Pokhrel2, B. R. Shah3,D. D. Bhatta1 1 Department of Livestock Services, Central Veterinary Laboratory, Kathmandu, Nepal 2 Agriculture and Forestry University, Chitwan, Nepal 3Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science, Tribhuvan University *Corresponding author: [email protected] ASBTRACT Despite the rapidly growing poultry industry throughout Nepal, the periodic outbreaks of diseases and infections in poultry birds led to huge production loss. The aim of this study was to identify the top ten poultry diseases in Nepal and an analysis of their seasonal distributions. A cross-sectional study was performed to describe the distributions of major poultry diseases diagnosed from April 2018 to April 2019 at Central Veterinary Laboratory, Nepal. Out of 2358 observations recorded at the CVL registry at that period, only 2271 observations qualified for the final analysis. Among 2271, removing the missing values, only 1915 observations were used to describe bird characteristics such as median age and mean flock sizes. Descriptive analysis and graphical representation was performed in R studio (Version 1.0.143) and MS excel 2010 respectively. The top ten diseases identified with highest to lowest incidence were: colibacillosis 26% (584/2271), mycotoxicosis 13% (301/2271), ascites 10% (232/2271), complicated chronic respiratory disease (cCRD) 9% (196/2271), infectious bursal disease (IBD) 7% (155/2271), Newcastle disease (ND) 7% (148/2271), avian influenza (AI) 3% (76/2271), salmonellosis 2% (40/2271), infectious bronchitis 1% (33/2271), coccidiosis 1% (25/2271) and non-specific diseases accounts for 21% (481/2271). -

MAAIF Poultry Manual

POULTRY TRAINING MANUAL For Extension Workers In Uganda Theme: Transforming Livelihoods through sustainable poultry production August 2019 !"#$%#$& TABLE OF FIGURES 5 LIST OF TABLES 7 PARTNERS 9 FORWARD AND ACKNOWLEDGMENT 10 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 11 MODULE 1: INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 12 1.1 Key stakeholders 13 1.2 Importance of poultry 14 1.3 Opportunities 14 1.4 Challenges 15 1.5 Ten suggested steps to a sustainable poultry enterprise 15 MODULE 2: POULTRY MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS IN UGANDA. 16 2.1 Types of poultry 16 2.2 Poultry breeds 16 2.3 Poultry management systems 17 2.3.1 Extensive system 17 2.3.2 Semi-intensive system 17 2.3.3 Intensive system 18 MODULE 3: POULTRY PRODUCTION PLANNING 20 3.1 Site selection 20 3.2 Farm lay out 20 3.3 Construction of a poultry house 21 3.3.1 Poultry house at the household level 22 3.3.2 Poultry house at commercial level 23 3.4 Poultry tools, equipment and other farm necessities 26 MODULE 4: POULTRY PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT 29 4.1 Brooder management 29 4.1.1 Qualities of a good brooder 30 4.1.2 Construction of a brooder 31 4.1.3 Key points to consider in brooder management 32 4.1.4 Ventilation 35 4.1.5 Temperature 36 4.1.6 Water 36 4.2 Management of layer breeders 38 4.2.1 Farm location and housing 38 4.2.2 Key objectives and activities in the grower period 38 4.2.3 Feeding program 38 4.2.4 Lighting program 40 4.2.5 Age at transfer 41 4.2.6 Stocking 42 4.2.7 Pecking 43 4.2.8 Prolapse 44 4.2.9 Smothering 44 4.2.10 Broodiness 45 4.2.11 Vaccinations 46 Poultry Training Manual for Extension Workers in Uganda -

Small-Scale Poultry Farming and Poverty Reduction in South Asia

SmallScale Poultry Farming and Poverty Reduction in South Asia From Good Practices to Good Policies in Bangladesh, Bhutan and India Ugo Pica‐Ciamarra (Animal Production and Health Division, FAO, Rome) and Mamta Dhawan (South‐Asia Pro‐Poor Livestock Policy Programme—SA PPLPP, New Delhi) December 2010 12 Suggested Citation: SA PPLPP (2010), “Small Scale Poultry Farming and Poverty Reduction in South Asia: From Good Practices to Good Policies in Bangladesh, Bhutan and India” Photo Credits: SA PPLPP Team © SA PPLPP (http://sapplpp.org/copyright) Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the National Dairy Development Board of India (NDDB) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitations of its frontiers or boundaries. The opinions expressed are solely of the author(s) and reviewer(s) and do not constitute in any way the official position of the NDDB or the FAO. Reproduction and dissemination of material from this document for educational or non commercial purposes is authorised without any prior written permission from the copyright holders, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material from this document for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holders. 1 The authors would like to thank Dr. A Saleque, Dr. Lham Tshering, Mr. S.E. Pawar, Dr. P.K. Shinde, Dr. D. V. Rangnekar, Dr. Kornel Das, Dr. -

2015 Annual Report NC1170 DRAFT Page: 1 Annual Report For

Annual Report for NC1170 Period Covered: January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2015 Prepared by: Douglas Rhoads Institutional Stations (Institutional Abbreviation: Members) Beckman Research Institute at the City of Hope (COH: M. Miller) Cornell University (CU: P. Johnson) Iowa State University (IA: S. Lamont, J.Dekkers) Michigan State University (MI: J. Dodgson, G. Strasburg) Mississippi State University (MS: C. McDaniel, B. Nanduri) North Carolina State University (NC: C. Ashwell, J. Petitte) Oregon State University (OR: D. Froman) Pennsylvania State University (PA: A. Johnston, R. Ramachandran) Purdue University (IN: W. Muir) University of Arizona (AZ: F. McCarthy, S. Burgess) University of Arkansas (AR: W. Kuenzel, B. Kong, D. Rhoads) University of California, Davis (CA: M. Delany, H. Zhou) University of Delaware (DE: B. Abasht) University of Georgia (GA: S. Aggrey) University of Maryland (MD: T. Porter, J. Song) University of Minnesota (MN: K. Reed) University of Tennessee‐Knoxville (TN: A. Saxton, B. Voy) Virginia Tech (VA: E. Wong, E. Smith) University of Wisconsin (WI: G. ROsa) USDA‐ARS‐Avian Disease and Oncology Lab (ADOL: H. Cheng, H. Zhang). Administration Executive Director‐ Jeff Jacobsen, Michigan State University Lakshmi Matukumalli‐ NIFA Representative Christina Hamilton‐ System Administration. NC1170 Business Meeting January 10, 2016 NC1170 BUSINESS MEETING 2016 Agenda: 1. Call to order 2. Approval of Agenda 3. Approval of 2015 minutes 4. Administrative Advisor: Sue Lamont 5. NIFA/USDA administrator: Lakshmi Matukumalli 6. NRSP8 Poultry co‐Coordinators: Delany and Cheng 2015 Annual Report NC1170 DRAFT Page: 1 7. Selection of secretary for NC1170 8. Selection of secretary for NRSP8 poultry 9. Location and time for meeting for 2017 10. -

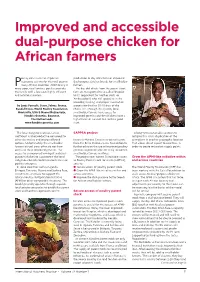

Improved and Accessible Dual-Purpose Chicken for African Farmers

Improved and accessible dual-purpose chicken for African farmers oultry constitutes an important production of day-old-chicks of improved economic activity for the rural poor in dual-purpose chicken breeds for smallholder Pmany African countries. Additionally in farmers. many poor, rural families, poultry provides The day-old-chicks from the parent stock the family with a low cost, highly efficient farm are transported to so called ‘Brooder and nutritious protein. Units’ (equivalent to ‘Mother Units’ or ‘Ambassadors’) who will specialise in the brooding, feeding, and proper vaccination by Louis Perrault, Sasso, Sabres, France, process for the first 30-40 days of the Randall Ennis, World Poultry Foundation, chicks’ life. Through this system, local Huntsville, USA & Naomi Duijvesteijn, smallholder farmers have access to Hendrix Genetics, Boxmeer, improved genetics and the chickens have a The Netherlands. high chance of survival due to their good www.hendrix-genetics.com start. The local indigenous breeds can be SAPPSA project A long-term sustainable solution to inefficient and unproductive compared to mitigate this risk is duplication of the other alternative and improved breed Recently Hendrix Genetics received a grant germplasm in another geographic location options. Unfortunately, the smallholder from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to that allows direct export to countries, in farmers in rural areas often do not have further enhance the use of improved poultry order to create redundant supply points. access to these improved genetics. The genetics to provide a better living to women access to an improved low-input and dual- smallholder farmers in Africa. purpose chicken to supplement the local The programme, named Sustainable Access Grow the APMI-like initiative within indigenous breeds could transform the rural to Poultry Parent Stock for Africa (SAPPSA), and across countries poultry enterprise. -

Genetic Analysis of Production Traits to Support Breeding Programs Utilizing Indigenous Chickens in Ethiopia

Breeding programs for indigenous chicken in Ethiopia Analysis of diversity in production systems and chicken populations Nigussie Dana 1 Thesis Committee Thesis supervisor Prof. dr. ir. J.A.M. van Arendonk Professor of Animal Breeding and Genetics Wageningen University, The Netherlands Thesis co-supervisors Dr. ir. E.H. van der Waaij Assistant professor Animal Breeding and Genetics Wageningen University, The Netherlands Dr. T. Dessie Research officer International Livestock Research Institute, Ethiopia Other Members Prof. dr. J. Sölkner BOKU University, Vienna (Austria) Prof. dr. M. C. H. de Jong Wageningen University (The Netherlands) Prof. dr. A.K. Kahi Egerton University (Kenya) Dr. G. A.A. Albers Hendrix Genetics, Boxmeer (The Netherlands) This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School of Wageningen Institute of Animal Sciences (WIAS). 2 Breeding programs for indigenous chicken in Ethiopia Analysis of diversity in production systems and chicken populations Nigussie Dana Thesis Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus, Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Friday 4 February 2011 at 4 p.m. in the Aula 3 Nigussie Dana Breeding programs for indigenous chicken in Ethiopia: analysis of diversity in production systems and chicken populations, 148 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands (2011) With summary in English and Dutch ISBN: 978-90-8585-872-0 4 Abstract The aim of this research was to generate information required to establish a sustainable breeding program for improving the productivity of locally adapted chickens to enhance the livelihood of rural farmers in Ethiopia. -

Hen Poultry Farming.Pdf

1 Profitable Hen Rearing Step-by-Step Guide Learn How To Make Serious Cash From Hens Rearing Agribusiness Copyright Written By : Timothy Angwenyi morebu (0714723004) Agribusiness Writer Copyright © 2016 by Timohbright. All rights reserved. First Edition: January 2016 Profitable Farming Guide Series This guide is geared towards providing exact and reliable information in regards to the topic and issue covered. In no way is it legal to reproduce, duplicate, or transmit any part of this document in either electronic means or in printed format. Recording of this publication is strictly prohibited and any storage of this document is not allowed unless with written permission from the writer. All rights reserved. 2 About The Writer Hello! My name is Timothy Angwenyi Morebu. My phone number is 0714723004. My email also is [email protected]. I am an Agribusiness writer, Agri-tourist & an Entrepreneur. Am currently writing guides on various ways of earning a living in Kenya through Profitable Farming (Entrepreneurship), whereby i educate Kenyans on business ideas to venture in Agriculture sector. Helping people start Agribusinesses and achieve the income they desire has become a huge part of my life. Being able to share the knowledge I have gained through visiting people's farms and attending Agriculture seminars and exhibitions has become extremely important to me. I consider my readers my friends. I am always so appreciative that they take their time out to read my eBook guides and to learn about Agribusiness ideas from me. Once you have finished reading this guide, I have no doubt that you will have learned a great deal about starting and running a profitable Hens Rearing Agribusiness in Kenya. -

International Network for Family Poultry Development

FFFAMILY POULTRY COMMUNICATIONS CCCOMMUNICATIONS EN AVICULTURE FAMILIALE CCCOMUNICACIONES EN AVICULTURA FAMILIAR Volume|Volumen 20 Number|Numéro|Número 2 July|Juillet|Julio – December|Décembre|Diciembre 2011 Published by | Publiées par | Publicado por INTERNATIONAL NETWORK FOR FAMILY POULTRY DEVELOPMENT RÉSEAU INTERNATIONAL POUR LE DÉVELOPPEMENT DE L'AVICULTURE FAMILIALE RED INTERNACIONAL PARA EL DESARROLLO DE LA AVICULTURA FAMILIAR www.fao.org/ag/againfo/themes/en/infpd/home.html Family Poultry Communications (FPC) |Communications en Aviculture Familiale (CAF) |Comunicaciones en Avicultura Familiar (CAF) Editor-in-Chief, FPC | Éditeur-en-Chef, CAF | Editor Principal, CAF Dr. E. Fallou Guèye, Regional Animal Health Centre for Western and Central Africa, B.P. 1820, Bamako, Mali, E-mail: <[email protected]> or <[email protected]> Associate Editor, FPC | Éditrice associée, CAF | Redactora Asociada, CAF Dr. Salimata Pousga, Université Polytechnique de Bobo-Dioulasso, 01 B.P. 1091, Bobo-Dioulasso 01, Burkina Faso, E-mail: <[email protected]> Spanish translator | Traducteur en Espagnol |Traductor en Español Mr. Mario Chanona Farrera, Av. Juan Crispin No. 455, Col. Plan de Ayala, C.P. 29,020, Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas, México, E-mail: <[email protected]> Coordinator, INFPD | Coordonnateur du RIDAF | Coordinador del RIDAF Prof. E. Babafunso Sonaiya, Department of Animal Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria, E-mail: <[email protected]> International Editorial Board | Comité Éditorial International | Comité de redacción Internacional I. Aini, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia ● R.G. Alders, International Rural Poultry Centre, Kyeema Foundation, Qld, Australia / Lubango, Angola ● J.G. Bell, United Kingdom ● R.D.S. Branckaert, France / Spain ● A. Cahaner, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rehovot, Israel ● A.J.