Una-Theses-0053.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

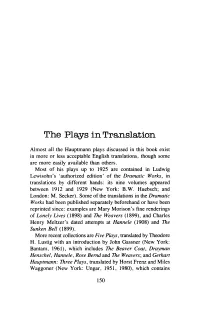

The Plays in Translation

The Plays in Translation Almost all the Hauptmann plays discussed in this book exist in more or less acceptable English translations, though some are more easily available than others. Most of his plays up to 1925 are contained in Ludwig Lewisohn's 'authorized edition' of the Dramatic Works, in translations by different hands: its nine volumes appeared between 1912 and 1929 (New York: B.W. Huebsch; and London: M. Secker). Some of the translations in the Dramatic Works had been published separately beforehand or have been reprinted since: examples are Mary Morison's fine renderings of Lonely Lives (1898) and The Weavers (1899), and Charles Henry Meltzer's dated attempts at Hannele (1908) and The Sunken Bell (1899). More recent collections are Five Plays, translated by Theodore H. Lustig with an introduction by John Gassner (New York: Bantam, 1961), which includes The Beaver Coat, Drayman Henschel, Hannele, Rose Bernd and The Weavers; and Gerhart Hauptmann: Three Plays, translated by Horst Frenz and Miles Waggoner (New York: Ungar, 1951, 1980), which contains 150 The Plays in Translation renderings into not very idiomatic English of The Weavers, Hannele and The Beaver Coat. Recent translations are Peter Bauland's Be/ore Daybreak (Chapel HilI: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), which tends to 'improve' on the original, and Frank Marcus's The Weavers (London: Methuen, 1980, 1983), a straightforward rendering with little or no attempt to convey the linguistic range of the original. Wedekind's Spring Awakening can be read in two lively modem translations, one made by Tom Osbom for the Royal Court Theatre in 1963 (London: Calder and Boyars, 1969, 1977), the other by Edward Bond (London: Methuen, 1980). -

37^ A8/J- //<5.Wc»7 GERHART HAUPTMANN: GERMANY THROUGH the EYES of the ARTIST DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council

37^ A8/J- //<5.Wc»7 GERHART HAUPTMANN: GERMANY THROUGH THE EYES OF THE ARTIST DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By William Scott Igo, B.S., M.Ed. Denton, Texas August, 1996 37^ A8/J- //<5.Wc»7 GERHART HAUPTMANN: GERMANY THROUGH THE EYES OF THE ARTIST DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By William Scott Igo, B.S., M.Ed. Denton, Texas August, 1996 1$/C. I go, William Scott, Gerhart Hauptmann: Germany through the eyes of the artist. Doctor of Philosophy (History), P / C if August, 1996, 421 pp., references, 250 entries. Born in 1862, Gerhart Hauptmann witnessed the creation of the German Empire, the Great War, the Weimar Republic, the Third Reich, and World War II before his death in 1946. Through his works as Germany's premier playwright, Hauptmann traces and exemplifies Germany's social, cultural, and political history during the late-nineteenth to mid- twentieth centuries, and comments on the social and political climate of each era. Hauptmann wrote more than forty plays, twenty novels, hundreds of poems, and numerous journal articles that reveal his ideas on politics and society. His ideas are reinforced in the hundreds of unpublished volumes of his diary and his copious letters preserved in the Prussian Staatsbibliothek, Berlin. In the 1960s, Germans celebrated Hauptmann's centenary as authors who had known or admired Hauptmann published biographies that chronicled his life but revealed little of his private thoughts. -

The Social Ideas in Hauptmann's Plays

The Social Ideas in Hauptmann's Plays uI Sarah Josephine Battle v CP— THE SOCIAL IDEAS IN HAUPTLIANK'S PLAYS by Sarah Josephine 3attle A Thesis submitted for the Degree of MASTER OB1 ARTS in the Department of MODERN LANGUAGES THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1925. INTRODUCTION To understand the conditions in the last decade of the nineteenth century in Germany which gave rise to the social drama of the naturalistic school, one must go back and trace the epoch-making changes which had been effected in Europe throughout the century. The old world order was becoming practically revolutionized by inventions and scientific discoveries. In the wake of the inventions and improvements of machinery, came business on a large scale, resulting in the influx of thousands of laborers into the cities which sprang up around the centres of industry. At first there was no supervision of the workers in the factories, and labor was ruthlessly exploited. The living conditions of the proletariat were deplorable, and the problem of the over-crowded disease- breeding slums was accordingly accentaated. The exploita tion of labor, however, was not confined to the cities. In the country there were many instances of sweated labor, and the misery of the Silesian weavers was particularly acute. A new class consciousness came into being with the great contrast between large fortunes, and the poverty of the underpaid workers, through whose toil this wealth had been amassed. The doctrines of Karl Llarx and the other socialistic writers of the period were an evidence of an ever growing social sympathy. -

Gerhart Hauptmann , Surely , Ought to Be More Widely Known in England Than He Actually Is

PR EFA"E THE aim of this essay is to give to the English ’ r eader an introduction to Hauptmann s works his t in their relation to life and char ac er . My wish is that it may act as a stimulus to r ead Hauptmann and to see productions of ta his plays on the s ge . For an author of the eminence of Gerhart Hauptmann , surely , ought to be more widely known in England than he actually is . If the style of the study is not hopelessly un- English it is no merit of mine , but the result of the kind assistance I obtained in its revision by my friends the Hon . Mrs . l o . Cha oner D wdall and Professor D J Sloss , and of the valuable suggestions of Professor Oliver Elton and Dr . Graham Brown . Mr . W . G . Jones most kindly read the proofs . I am indebted to Professor H . G . Fiedler for kindly supplying me with some biographical x Preface s R note , and to my friend Professor Petsch for lending me a copy of the rare Pro methidenlos and for freely offering his valu able advice . To all of them I express my heartfelt thanks . Part of this study was first delivered as an ’ address to the Liverpool Playgoers Soc iety on ’ the eve of Hauptmann s fiftieth birthday , and 6 was repeated to the Leeds Playgoers on March , 1 . 1 9 3. K . H "ON T EN T S "HAPTER A ’ G E RHART HA U PT MA N N S LIF E F ROM 1 862 —1 889 "HAP TER B L I T ERAR Y T ENDEN"IES OF HIS T IM E "HAPT ER " ’ G ERHART H AU PT MANN S WOR K F ROM 1 889- 1 9 I2 S I . -

Hauptmann's the Weavers As "Social Sculpture" Margaret Sutherland

Hauptmann's The Weavers as "Social Sculpture" Margaret Sutherland Gerhart Hauptmann (1862-1946) was one of Germany's best known and most prolific writers during the latter part of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century. The colossal impact of his dramas, prose works, essays and other writing is reflected in the many honorary doctorates, and countless awards that he received throughout his life, including the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1912. 1 Thomas Mann's words on the occasion of Hauptmann's 701" birthday in 1932 give some insight into his work: He did not speak in his own guise, but let life itself talk with the tongues of changing, active human beings. He was neither a man of letters nor a rhetorician, neither an analyst nor a formal dialectician; his dialectic was that of life itself; it was human drama. 2 It is not surprising that Hauptmann was not a man of letters, given that his family was not considered to be particularly literary and he himself was not very academically inclined at school. His mother even encouraged him to pursue a career in gardening! 3 It was as a schoolboy, however, that he first came into contact with the theatre. Warren Maurer reports that he had been intrigued by the spa theatre in his home town and had played with a cardboard Hamlet and stage as a small child. His first direct theatrical experience was said to be at the Breslau Theatre where he saw the famous Meininger troupe's productions of such dramas as 1 This was awarded primarily for The Weavers.