Black Music Research Journal How the Creole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

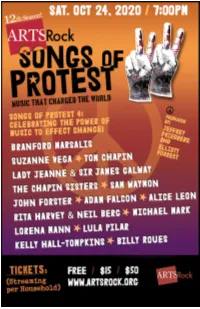

Songs-Of-Protest-2020.Pdf

Elliott Forrest Dara Falco Executive & Artistic Director Managing Director Board of Trustees Stephen Iger, President Melanie Rock, Vice President Joe Morley, Secretary Tim Domini, Treasurer Karen Ayres Rod Greenwood Simon Basner Patrick Heaphy David Brogno James Sarna Hal Coon Lisa Waterworth Jeffrey Doctorow Matthew Watson SUPPORT THE ARTS Donations accepted throughout the show online at ArtsRock.org The mission of ArtsRock is to provide increased access to professional arts and multi-cultural programs for an underserved, diverse audience in and around Rockland County. ArtsRock.org ArtsRock is a 501 (C)(3) Not For-Profit Corporation Dear Friends both Near and Far, Welcome to SONGS OF PROTEST 4, from ArtsRock.org, a non- profit, non-partisan arts organization based in Nyack, NY. We are so glad you have joined us to celebrate the power of music to make social change. Each of the first three SONGS OF PROTEST events, starting in April of 2017, was presented to sold-out audiences in our Rockland, NY community. This latest concert, was supposed to have taken place in-person on April 6th, 2020. We had the performer lineup and songs already chosen when we had to halt the entire season due to the pandemic. As in SONGS OF PROTEST 1, 2 & 3, we had planned to present an evening filled with amazing performers and powerful songs that have had a historical impact on social justice. When we decided to resume the series virtually, we rethought the concept. With so much going on in our country and the world, we offered the performers the opportunity to write or present an original work about an issue from our current state of affairs. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

EB and Bechet Were Buddies, and They Would Go to Dances, Taking Their

r. * EMILE BARNES 1 Reel I [of 2]-Digest-Retype December 20, 1960 * Also present: William Russell, Ralph Collihs. .\ There is discussion of clarinets and mouthpieces; EB says that he first started playing using a wooden mouthpiece, which he found better than any other kind of mouthpiece; it was stolen, with his clarinet, and he finally became accustomed.to hard-rubber mouth- piecesr which he formerly sandpapered to fit his requirements. RC mentions that Raymond Burke also makes adjustments on his own mouth- pieces* WB says that Professor [Manuel] Manetta had a Buffet clari- net which he got from George Baquet; WR asks EB if he can tell any- thing about B&quet, EB says that Baquet had fire in his playing, that he had a loud tone, played a lot of variations. EB says Sidney Bechet played somewhat like early Baquet [c£. their records] EB tells how Eechet could take his clarinet apart, joint by joint from the bottom, and still play it. EB says that Bechet used to ^ ^ r, -1 f i^ f .-Ji \. "cut hay'\ [perhapsh this means that he would search for someone to 'beat. playing the clarinet], that he would go around to places where there were good clarinetists-like Baquet, [Alphonse] Picou and [Lorenzo] Tio, [Jr,]-[the inference is that Bechet could play better.] EB and Bechet were buddies, and they would go to dances, taking their clarinets in their back pockets, anywhere there was one. EB was about 17 years old at the time, Bechet a little younger; both wore short pants; S^ys Bechet was a'bout 63 [when he died in 1959]. -

Inventory of American Sheet Music (1844-1949)

University of Dubuque / Charles C. Myers Library INVENTORY OF AMERICAN SHEET MUSIC (1844 – 1949) May 17, 2004 Introduction The Charles C. Myers Library at the University of Dubuque has a collection of 573 pieces of American sheet music (of which 17 are incomplete) housed in Special Collections and stored in acid free folders and boxes. The collection is organized in three categories: African American Music, Military Songs, and Popular Songs. There is also a bound volume of sheet music and a set of The Etude Music Magazine (32 items from 1932-1945). The African American music, consisting of 28 pieces, includes a number of selections from black minstrel shows such as “Richards and Pringle’s Famous Georgia Minstrels Songster and Musical Album” and “Lovin’ Sam (The Sheik of Alabami)”. There are also pieces of Dixieland and plantation music including “The Cotton Field Dance” and “Massa’s in the Cold Ground”. There are a few pieces of Jazz music and one Negro lullaby. The group of Military Songs contains 148 pieces of music, particularly songs from World War I and World War II. Different branches of the military are represented with such pieces as “The Army Air Corps”, “Bell Bottom Trousers”, and “G. I. Jive”. A few of the delightful titles in the Military Songs group include, “Belgium Dry Your Tears”, “Don’t Forget the Salvation Army (My Doughnut Girl)”, “General Pershing Will Cross the Rhine (Just Like Washington Crossed the Delaware)”, and “Hello Central! Give Me No Man’s Land”. There are also well known titles including “I’ll Be Home For Christmas (If Only In my Dreams)”. -

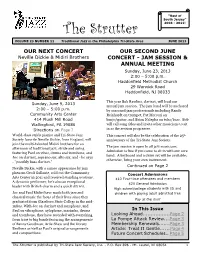

The Strutter 2008 - 2011!

“Best of South Jersey” The Strutter 2008 - 2011! VOLUME 23 NUMBER 11 Traditional Jazz in the Philadelphia Tri-State Area JUNE 2013 OUR NEXT CONCERT OUR SECOND JUNE Neville Dickie & Midiri Brothers CONCERT - JAM SESSION & ANNUAL MEETING Sunday, June 23, 2013 2:00 – 5:00 p.m. Haddonfield Methodist Church 29 Warwick Road Haddonfield, NJ 08033 This year Bob Rawlins, clarinet, will lead our Sunday, June 9, 2013 annual jam session. The jam band will be anchored 2:00 – 5:00 p.m. by seasoned jazz professionals including Randy Community Arts Center Reinhardt on trumpet, Pat Mercuri on 414 Plush Mill Road banjo/guitar, and Brian Nalepka on tuba/bass. Bob Wallingford, PA 19086 will call song titles and invite other musicians to sit Directions on Page 7 in as the session progresses. World-class stride pianist and Tri-State Jazz This concert will also be the celebration of the 25th Society favorite Neville Dickie, from England, will anniversary of the Tri-State Jazz Society. join the multi-talented Midiri brothers for an The jam session is open to all jazz musicians. afternoon of traditional jazz, stride and swing Admission is free if you come to sit in with our core featuring Paul on vibes, drums and trombone, and band. A keyboard and a drum set will be available; Joe on clarinet, soprano sax, alto sax, and - he says otherwise, bring your own instrument. - "possibly bass clarinet." Continued on Page 2 Neville Dickie, with a cameo appearance by jazz phenom Geoff Gallante, sold out the Community Concert Admissions Arts Center in 2011 and received standing ovations. -

Mr. Gamer LINCOLN ROCKETS Wear a Ten Pretty and Clever TERPSICHOREAN ARTISTS Strap Watch of New Haven, Connecticut Beaver's- - Novelty Orchestra ORPHEUM Nite and Mat

T If E DAILY NEBRASKAN Buildings Cig.r.tt.. Construct Young Coolldgo is a junior at Am- herst Records Are Given To Talk Over Income from college. Ho is just a plain, or- Dr. Harms Gives Radio South Dakota the College Press dinary Is used solely fellow, and mado out of the. Two Years Ago German Department; .tato cigarette tax same on Adenoid Conditions 2 of at kind of cluy as the rest of us KFAB construction building I Will Be Used in Class he POOR JOHN nis and, according to Dolitical and advor. Eleanor Flatemersh was officially ?.U colleges (Wisconsin Daily Cardinal.) tiHementa used to pitch hay symptoms of enlarged ing to Doctor Harms. The tendency Sough cigarette, wtfte consumed and milk appointed president of tho Women's Causes and Thoso of us who squirm under tho cows on a farm in Vermont. Young Throgh cho generosity of some diseased adenoids and the bad to havo enlarged adenoids is also her- Jurlnlt past year to erect two Athletic Association. Eleanor was a and the allegod injustices of W. S. G. A. rules John was developing normally friends of tho German department, such a condition, especially editary In somo families. like mombor of Alpha XI Delta, Silver effects of consider ourselves lucky that wo ore any other American boy Prof. Laurence Foaslcr and his staff in case of children, wero dis Tho commonest symptom and most when a great Sorpcnt, Vestals, and tho Y. W. C. A. the not the son of President Coolidge. minfortuno happened to him. For havo become tho owner and custo cussed by Dr. -

John Edward Hasse Collection Ca. 2004 Copies (Ca

Collection # P 0470 JOHN EDWARD HASSE COLLECTION CA. 2004 COPIES (CA. 1910S–1920S) Collection Information Biographical Sketches Scope and Content Note Series Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Barbara Quigley 27 October 2005 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 1 black-and-white photograph folder; 1 color photograph folder COLLECTION: COLLECTION Ca. 2004 copies (ca. 1910s–1920s) DATES: PROVENANCE: Gift from John Edward Hasse of the Smithsonian Institution. RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 0000.0412 NUMBER: NOTES: The William Henry Smith Memorial Library holds several publications authored by John Edward Hasse. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES Indianapolis was a rich center of ragtime and jazz in the early twentieth century. Ragtime, a uniquely American musical genre based on African-American rhythms, flourished throughout the United States from the late 1890s to the end of World War I. There were several distinguished ragtime composers and performers in Indianapolis during that time. Many were African-Americans who performed along Indiana Avenue, but little of their music was published. Most of the published composers were middle class whites, including numerous women. The city’s ragtime community included May Aufderheide, Cecil Duane Crabb, Will B. Morrison, Julia Lee Niebergall, J. Russel Robinson, and Gladys Yelvington. In the early twentieth century jazz was created primarily by African-Americans. Indianapolis was a favorite destination for touring musical shows, and there was much work for local musicians. -

Glenn Miller Archives

Glenn Miller Archives ARTIE SHAW INDEX Prepared by: Reinhard F. Scheer-Hennings and Dennis M. Spragg In Cooperation with the University of Arizona Updated December 11, 2020 Table of Contents 2.1 Recording Sessions 3 2.2 Broadcasts (Recordings) 4 2.3 Additional Broadcasts (Data Only) 8 2.4 Personal Appearances 13 2.5 Music Library 16 2.6 On The Record 82 2.6.1 Analog Media 83 2.6.2 Digital Media 143 2.7 Glenn Miller Archives 162 2.7.1 Analog Media 163 RTR Edward Burke Collection 163 2.7.2 Digital Media 164 EHD Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) 164 EHD Mutual Broadcasting System (MBS) 165 EHD National Broadcasting Company (NBC) 165 2.8 Star Spangled Radio Hour 167 Cover: Artie Shaw 1940 Paramount Publicity Photo P-2744-6 (Glenn Miller Archives) 2 2.1 Recording Sessions 38-07-24 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio #2, New York 38-09-27 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio #2, New York 38-11-17 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio #2, New York 38-11-28 Vitaphone Melody Master (Film), Warner Brothers, New York 38-12-19 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio #2, New York 39-01-17 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio #2, New York 39-01-23 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio #2, New York 39-01-31 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio #2, New York 39-03-00 Vitaphone Melody Master (Film), Warner Brothers, New York 39-03-12 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio #2, New York 39-03-17 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio #2, New York 39-03-19 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio #2, New York 39-06-05 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio, Hollywood 39-06-12 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio, Hollywood 39-06-22 Bluebird Recording Session, Victor Studio, Hollywood 39-06-00 Paramount Headliner (Film), Paramount Studios, Hollywood 39-07-15 MGM Prerecording Session, MGM Studio, Culver City, Cal. -

Florida Repertory Theatre 2 0

FLORIDA REPERTORY THEATRE 2015-2016 SEASON ARTSTAGE STUDIO THEATRE • FORT MYERS RIVER DISTRICT ROBERT CACIOPPO, PRODUCING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PRESENTS Featuring the Lyrics of JOHNNY MERCER Music by JEROME KERN, HENRY MANCINI, DUKE ELLINGTON, HAROLD ARLEN, & More Conceived, Written and Directed by ROBERT CACIOPPO SPONSORED BY THE GALLOWAY FAMILY OF DEALERSHIPS AND MADELEINE TAENI STARRING JOE BIGELOW* • DAVID EDWARDS* • JULIE KAVANAGH* • JAMES DAVID LARSON* MICAHEL McASSEY* • SOARA-JOYE ROSS* DIRECTED BY ensemble member ROBERT CACIOPPO** MUSIC DIRECTOR CHOREOGRAPHER SET DESIGNER MICHAEL McASSEY ARTHUR D’ALESSIO TIM BILLMAN LIGHTING DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER TODD O. WREN*** DINA PEREZ*** JOHN KISELICA ensemble member PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER ASST. STAGE MANAGER AMY L. MASSARI* GRACIE DOD ensemble member 2015-16 GRAND SEASON SPONSORS Anonymous • The Fred & Jean Allegretti Foundation • Naomi Bloom & Ron Wallace Bruce & Janet Bunch • Gholi & Georgia Darehshori • Ed & Ellie Fox • Dr. & Mrs. Mark & Lynne Gorovoy John & Marjorie Madden • Sue & Jack Rogers • Arthur Zupko This entire season sponsored in part by the State of Florida, Department of State, Division of Cultural Affairs, and the Florida Council on Arts and Culture. Florida Repertory Theatre is a fully professional non-profit LOA/LORT Theatre company on contract with the Actors’ Equity Association that proudly employs members of the national theatrical labor unions. *Member of Actors’ Equity Association. **Member of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society. ***Member of United Scenic Artists. CAST JOE BIGELOW* DAVID EDWARDS* JULIE KAVANAGH* JAMES DAVID LARSON* MICHAEL MCASSEY* SOARA-JOYE ROSS* Bartender: Kyle Ashe Wilkinson/Ryan Gallerani TOO MARVELOUS FOR WORDS: A SALUTE TO JOHNNY MERCER will be performed with one 15-minute intermission. -

A Researcher's View on New Orleans Jazz History

2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Format 6 New Orleans Jazz 7 Brass & String Bands 8 Ragtime 11 Combining Influences 12 Party Atmosphere 12 Dance Music 13 History-Jazz Museum 15 Index of Jazz Museum 17 Instruments First Room 19 Mural - First Room 20 People and Places 21 Cigar maker, Fireman 21 Physician, Blacksmith 21 New Orleans City Map 22 The People Uptown, Downtown, 23 Lakefront, Carrollton 23 The Places: 24 Advertisement 25 Music on the Lake 26 Bandstand at Spanish Fort 26 Smokey Mary 26 Milneburg 27 Spanish Fort Amusement Park 28 Superior Orchestra 28 Rhythm Kings 28 "Sharkey" Bonano 30 Fate Marable's Orchestra 31 Louis Armstrong 31 Buddy Bolden 32 Jack Laine's Band 32 Jelly Roll Morton's Band 33 Music In The Streets 33 Black Influences 35 Congo Square 36 Spirituals 38 Spasm Bands 40 Minstrels 42 Dance Orchestras 49 Dance Halls 50 Dance and Jazz 51 3 Musical Melting Pot-Cotton CentennialExposition 53 Mexican Band 54 Louisiana Day-Exposition 55 Spanish American War 55 Edison Phonograph 57 Jazz Chart Text 58 Jazz Research 60 Jazz Chart (between 56-57) Gottschalk 61 Opera 63 French Opera House 64 Rag 68 Stomps 71 Marching Bands 72 Robichaux, John 77 Laine, "Papa" Jack 80 Storyville 82 Morton, Jelly Roll 86 Bolden, Buddy 88 What is Jazz? 91 Jazz Interpretation 92 Jazz Improvising 93 Syncopation 97 What is Jazz Chart 97 Keeping the Rhythm 99 Banjo 100 Violin 100 Time Keepers 101 String Bass 101 Heartbeat of the Band 102 Voice of Band (trb.,cornet) 104 Filling In Front Line (cl. -

U.S. Sheet Music Collection

U.S. SHEET MUSIC COLLECTION SUB-GROUP II: THEMATIC ARRANGEMENT Patriotic Leading national songs . BOX 458 Other patriotic music, 1826-1899 . BOX 459 Other patriotic music, 1900– . BOX 460 National Government Presidents . BOX 461 Other national figures . BOX 462 Revolutionary War; War of 1812 . BOX 463 Mexican War . BOX 464 Civil War . BOXES 465-468 Spanish-American War . BOX 469 World War I . BOXES 470-473 World War II . BOXES 474-475 Personal Names . BOXES 476-482 Corporate Colleges and universities; College fraternities and sororities . BOX 483 Commercial entities . BOX 484 Firemen; Fraternal orders; Women’s groups; Militia groups . BOX 485 Musical groups; Other clubs . BOX 486 Places . BOXES 487-493 Events . BOX 494 Local Imprints Buffalo and Western New York imprints . BOXES 495-497 Other New York state and Pennsylvania imprints . BOX 498 Rochester imprints . BOXES 499-511 Selected topics Abolition; Crime; Fashion; Sports; Temperance; Miscellaneous . BOX 512 Other special imprints Additional Pennsylvania imprints; Pennsylvania connections . BOX 513 Box 458 Ascher, Gustave, arr. America: My Country Tis of Thee. For voice and piano. In National Songs. New York: S. T. Gordon, 1861. Carey, Henry, arr. America: The United States National Anthem. For voice and piano. [s.l.: s.n., s.d.]. Loose sheet on cardboard. On reverse of publication: Anne Fricker. I built a Bridge of Fancies. For voice and piano. Philadelphia: Sep. Winner & Sons, [s.d.]. Smith, Samuel Francis. America: My Country! ‘Tis of Thee. For TTB voices and piano. Arranged by Harold Potter. New York: Mills Music Co., 1927. Shaw, David T. Columbia: The Land of the Brave.