Modernism and the Growing Catholic Identity Problem: Thomistic Reflections and Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Method in American Catholic Moral Eology a Er Veritatis Splendor

Journal of Moral eology, Vol. 1, No. 1 (2012): 170-192 REVIEW ESSAY Method in American Catholic Moral eology Aer Veritatis Splendor DAVID CLOUTIER and WILLIAM C. MATTISON III UR PURPOSE in this inaugural issue of the Journal of Moral eology is to reflect on the state of“ method” in Catholic moral theology today. But rather than present a set of essays, each representing a different method or “Oschool,” we chose to invite authors at institutions training American Catholic moral theologians to write essays reflecting on the influence of a diverse set of thinkers, thinkers who both immediately preceded and particularly influenced American Catholic moral theology today. We hope that presenting a set of essays by these current shapers of American Catholic moral theologians, about recent influential fig- ures, will provide a lens into what characterizes Catholic moral the- ology today. So, does this decision about how to reflect on methodology reveal that American Catholic moral theology today in fact has no “meth- od”? Certainly as compared with pre-Vatican II Catholic theology of all subdisciplines, which Gerard McCool describes as marked by a “search for a unitary method,”1 moral theology today does not pre- sent a straightforward unified methodology. Yet to say “there is no method” says too little. Such a claim could wrongly suggest that there 1 Gerard McCool, Nineteenth Century Scholasticism: e Search for a Unitary Meth- od (New York: Fordham University Press, 1989). Method in American Catholic Moral eology 171 are no identifiable parameters in the discipline of Catholic moral theology today. It could also fan the flames of a reactionary trend seeking refuge in the perceived order of pre-Vatican II moral theolo- gy, a move that, moreover, has no real support in the work of Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI. -

The Holy See

The Holy See IOANNES PAULUS PP. II EVANGELIUM VITAE To the Bishops Priests and Deacons Men and Women religious lay Faithful and all People of Good Will on the Value and Inviolability of Human Life INTRODUCTION 1. The Gospel of life is at the heart of Jesus' message. Lovingly received day after day by the Church, it is to be preached with dauntless fidelity as "good news" to the people of every age and culture. At the dawn of salvation, it is the Birth of a Child which is proclaimed as joyful news: "I bring you good news of a great joy which will come to all the people; for to you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, who is Christ the Lord" (Lk 2:10-11). The source of this "great joy" is the Birth of the Saviour; but Christmas also reveals the full meaning of every human birth, and the joy which accompanies the Birth of the Messiah is thus seen to be the foundation and fulfilment of joy at every child born into the world (cf. Jn 16:21). When he presents the heart of his redemptive mission, Jesus says: "I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly" (Jn 10:10). In truth, he is referring to that "new" and "eternal" life 2 which consists in communion with the Father, to which every person is freely called in the Son by the power of the Sanctifying Spirit. It is precisely in this "life" that all the aspects and stages of human life achieve their full significance. -

The Holy See

The Holy See MESSAGE OF THE HOLY FATHER ON THE OCCASION OF THE 14TH WORLD YOUTH DAY “The Father loves you” (cf. Jn 16:27) Dear young friends! 1. In the perspective of the Jubilee which is now drawing near, 1999 is aimed at “broadening the horizons of believers so that they will see things in the perspective of Christ: in the perspective of the 'Father who is in heaven' from whom the Lord was sent and to whom he has returned” (Tertio Millennio Adveniente, 49). It is, indeed, not possible to celebrate Christ and his jubilee without turning, with him, towards God, his Father and our Father (cf. Jn 20:17). The Holy Spirit also takes us back to the Father and to Jesus. If the Spirit teaches us to say: “Jesus is Lord” (cf. 1Cor 12:3), it is to make us capable of speaking with God, calling him “Abba! Father!” (cf. Gal 4:6). I invite you also, together with the whole Church, to turn towards God the Father and to listen with gratitude and wonder to the amazing revelation of Jesus: “The Father loves you!” (cf. Jn 16:27). These are the words I entrust to you as theme for the XIV World Youth Day. Dear young people, receive the love that God first gives you (cf. 1Jn 4:19). Hold fast to this certainty, the only one that can give meaning, strength and joy to life: his love will never leave you, his covenant of peace will never be removed from you (cf. Is 54:10). -

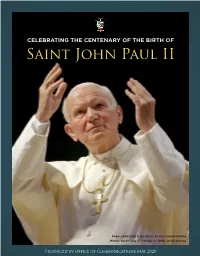

Saint John Paul II

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission. -

'A New Imagination of the Possible': Seven Images from Francis for Post

‘A New Imagination of the Possible’: Seven Images from Francis for post-Covid-19 Add to Favorites Antonio Spadaro, SJ / Church Life / 14 July 2020 The first global pandemic of the digital age arrived suddenly. The world was stopped in its tracks by an unnatural suspension of activity that interrupted business and pleasure. “For weeks now it has been evening. Thick darkness has gathered over our squares, our streets and our cities; it has taken over our lives, filling everything with a deafening silence and a distressing void that stops everything as it passes by. We feel it in the air, we notice in people’s gestures, their glances give them away. We find ourselves afraid and lost.” These are the words Pope Francis used to portray the unprecedented situation. He pronounced them on March 27 before a completely empty Saint Peter’s Square, during an evening of Eucharistic adoration and an Urbi et Orbi blessing that was accompanied only by the sound of church bells mixed with ambulance sirens: the sacred and the pain. The pope has also stated that this crisis period caused by the Covid-19 pandemic is “ a propitious time to find the courage for a new imagination of the possible, with the realism that only the Gospel can offer us.”[1] The thick darkness, then, allows us to find the courage to imagine. How was it possible to send out such a message in a moment of depression and fear? We are accustomed to the probable, to what our minds suppose should happen, statistically speaking. -

Topical Index

298 The Moral Life in Christ Index Page numbers in color indicate illustrations. Titles of paintings will be found under the name of the artist, unless they are anonymous. References to specific citations from Scripture and the Catechism will be found in the separate INDEX OF CITATIONS. A art and music in Church, 130 sanctifying grace in, 33, 34, atheism, 119, 124 235, 250–252, 287, 288 attractiveness. See sexuality Barzotti, Biagio, Pope abortion and abortion laws, Leo XIII with Cardinals St. Augustine of Hippo 50, 82, 88, 90–91, 103 Rampolla, Parochi, on Baptism, 43 Abraham, 103 Bonaparte, and Sacconi (ca. Benedict XVI on, 14 absolution, 148, 286 1890), 114 Champaigne, Philippe de, abstinence, 99, 175, 286 Baudricourt, Robert, 239 Saint Augustine (ca. 1650), Baumgartner, Johan acedia, 66, 286 212 Wolfgang, The Prodigal Son actual grace, 235, 286 Confessions, 12 Wasting his Inheritance (1724- Adam and Eve on Eternal Law, 58–59 1761), 6 marriage and, 108 on freedom, 9 beatitude, 34, 120, 193. See Original Justice and, 19 on grace, 246 also holiness Original Sin and, 17–22, 24, on happiness, 47 Beatitudes, 145, 147–150, 26, 33, 206, 293 152–154, 161, 165, 286 life of, 7 adoration, 275, 277, 286 Benedict XVI (pope) on love, 89 adulation, 129, 130, 286 Caritas in Veritate (papal passions and, 212 adultery, 93, 94, 102, 286 encyclical, 2009), 117–118 on prayer, 283 alcohol and drugs, 84, 141 Deus Caritas Est (papal Retractationes, 28 encyclical, 2005), 13–14 almsgiving, 123, 257, 286 On the Sermon on the general audience, Nov. -

A Conversion … in the Language We Use”1

MELITA THEOLOGICA Paul Pace Journal of the Faculty of Theology Nadia Delicata University of Malta 65/1 (2015): 75–96 “A Conversion … in the Language We Use”1 Introduction ope Francis’ challenge to seek and find an adequate pastoral response to Pnew family situations needs to be taken up boldly. There is no doubt that an important way of doing this is to reflect on the way we, as Church, consider family issues ad intra, but we also need to look at how we seek to communicate truths about the family with and to the world. Is the “Gospel of the Family” offering hope and joy to those in the fold who are struggling with complex family situations? Is it encouraging the conversion of those often deemed to be on the “margins” of the Church? Is our message about family life persuasive – in particular, in our case, in a strongly secularist European context? Reflection not just about the “message” but also about the way it is communicated is a key challenge for theologians, always called to read the signs of the times and to interpret the Gospel afresh. It is pivotal for ministers and church leaders called to guide the faithful along the steps of their pilgrim journey. It is also necessary for the Church’s task of evangelization in a post-Christian continent in particular, and in the “global village” at large. The challenge is that of finding a new language that speaks to the various audiences to whom we, as Church, are sent to share and proclaim the Gospel. -

The Use of Philosophical Principles in Catholic Social Thought: the Case of Gaudium Et Spes

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 45 Number 2 Volume 45, 2006, Number 2 Article 6 The Use of Philosophical Principles in Catholic Social Thought: The Case of Gaudium et Spes Rev. Joseph W. Koterski, S.J. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE USE OF PHILOSOPHICAL PRINCIPLES IN CATHOLIC SOCIAL THOUGHT: THE CASE OF GAUDIUM ET SPES REVEREND JOSEPH W. KOTERSKI, S.J.t It is common to find individuals who are very attracted to questions of social justice and others quite uninterested, or even suspicious.1 At both extremes there are dangers to avoid. On the one hand, Catholicism may never be reduced to the concerns of "the social gospel" apart from the rest of the faith.2 On the other hand, the Church's social teachings, especially in the clear articulation given by recent popes and the Second Vatican Council, are not peripheral to the faith, not something purely optional, as if the essence of Catholicism were a matter of spirituality to the exclusion of morality.3 Like the rest of Catholic moral theology, Catholic Social Teaching (CST) has roots both in revelation and reason,4 and anyone interested in t Rev. Joseph W. -

Sentire Cum Ecclesia) Susan K

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Theology Faculty Research and Publications Theology, Department of 2-6-2019 Thinking and Feeling with the Church (Sentire Cum Ecclesia) Susan K. Wood Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted version. Ecclesiology, Vol. 15, No. 1 (February 6, 2019): 3-6. DOI. © 2019 Brill Academic Publishers. Used with permission. Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Theology Faculty Research and Publications/College of Arts and Sciences This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; but the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation below. Ecclesiology, Vol. 15, No. 1 (February 6, 2019): 3-6. DOI. This article is © Brill Academic Publishers and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Brill Academic Publishers does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Brill Academic Publishers. Thinking and Feeling with the Church (Sentire Cum Ecclesia) Susan K. Wood Marquette University, Wisconsin In the sixteenth century, St. Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), the founder of the Society of Jesus, developed eighteen rules for ‘thinking with the church’ (sentire cum ecclesia) in his Spiritual Exercises. In many ways, it is an odd list that gives witness to its post-Reformation provenance. It includes such things as commending the confession of sins to a priest and frequent assistance at mass, approval of religious vows, veneration of relics, abstinence and fasts, and not speaking of predestination frequently. The historian reads these against the predestination of Calvin’s doctrine, Luther’s critique of monasticism, and the Reformation criticism of masses offered for the dead. -

The Emergence of a Lay Esprit De Corps: Inspirations, Tensions, Horizons

Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal Volume 8 Number 2 Article 3 2019 The Emergence of a Lay Esprit de Corps: Inspirations, Tensions, Horizons Christopher Pramuk Regis University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/jhe Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Practical Theology Commons, Religious Education Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Commons Recommended Citation Pramuk, Christopher (2019) "The Emergence of a Lay Esprit de Corps: Inspirations, Tensions, Horizons," Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal: Vol. 8 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://epublications.regis.edu/jhe/vol8/iss2/3 This Scholarship is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Emergence of a Lay Esprit de Corps: Inspirations, Tensions, Horizons Cover Page Footnote This essay is dedicated in memoriam to Fr. Howard Gray, SJ, whom I never had the good fortune to meet, but whose impact on me and so many in the realm of Jesuit education and Ignatian spirituality continues to be immense. This scholarship is available in Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal: https://epublications.regis.edu/jhe/vol8/iss2/3 Pramuk: The Emergence of a Lay Esprit de Corps The Emergence of a Lay Esprit de Corps: Inspirations, Tensions, Horizons Christopher Pramuk University Chair of Ignatian Thought and Imagination Associate Professor of Theology Regis University [email protected] Abstract Likening the Ignatian tradition as embodied at Jesuit universities to a family photo album with many pages yet to be added, the author locates the “heart” of the Ignatian sensibility in the movements of freedom and spirit (inspiration) in the life of the community. -

Pastoral Letter on the Reading of Amoris Laetitia In

PASTORAL LETTER ON THE READING OF AMORIS LAETITIA IN LIGHT OF CHURCH TEACHING “A TRUE AND LIVING ICON” OF THE ARCHBISHOP OF PORTLAND, OREGON MOST REVEREND ALEXANDER K. SAMPLE TO THE PRIESTS, DEACONS, RELIGIOUS AND FAITHFUL OF THE ARCHDIOCESE “The couple that loves and begets life is a true, living icon … capable of revealing God the Creator and Savior.”1 With these words our Holy Father, Pope Francis, reminds us that married love is “a symbol of God’s inner life,” for the “triune God is a communion of love, and the family is its living reflection.”2 Of its very nature, marriage exists for the communion of life and love between spouses, ordered to the procreation and care of children, in an exclusive and permanent bond between one man and one woman. In this natural bond, existing even between unbaptized spouses, we are given “an image for understanding and describing the mystery of God himself.…”3 Christ our Lord elevated the natural bond of marriage to the dignity of a sacrament whereby the union of man and woman signifies the “union of Christ and the Church.”4 God, who is eternal and unchanging, gives marriage as a natural icon of himself; Christ elevates marriage into a sacrament signifying the permanent, indissoluble covenant with his people. Because the family is essential to the well-being of the world, the Church, and the spread of the Gospel, the world’s bishops gathered in the Synods of 2014 and 2015 to identify the real situation of marriages and families in the world today and to seek pastoral solutions for these challenges. -

John Paul II and the Law

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 21 Article 7 Issue 1 Symposium on Pope John Paul II and the Law 1-1-2012 John Paul II: Migrant Pope Teaches on Unwritten Laws of Migration Nicholas DiMarzio Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Nicholas DiMarzio, John Paul II: Migrant Pope Teaches on Unwritten Laws of Migration, 21 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 191 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol21/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN PAUL II: MIGRANT POPE TEACHES ON UNWRITTEN LAWS OF MIGRATION MOST REVEREND NICHOLAS DiMARzio, PH.D., D.D.* INTRODUCTION His Holiness, John Paul II, of happy memory, was one of the greatest teaching popes in the Church's history. He has given the Church a body of teaching that will take generations to fathom. This issue of the Notre DameJournal of Law, Ethics & Pub- lic Policy is an attempt to collate his teaching regarding law and public policy. This article will attempt to bring together John Paul II's thought and teaching on migration, which is implicit in many of his teachings, and also explicit in many of his discourses. Underlying his teaching is an understanding of human dignity which became the departure point forJohn Paul II's understand- ing of natural law.