Gwo Ka, from the Twentieth Century to the Present Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Rey Vallenato De La Academia Camilo Andrés Molina Luna Pontificia

EL REY VALLENATO DE LA ACADEMIA CAMILO ANDRÉS MOLINA LUNA PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD JAVERIANA FACULTAD DE ARTES TESIS DE PREGRADO BOGOTÁ D.C 2017 1 Tabla de contenido 1.Introducción ........................................................................................................ 3 2.Objetivos ............................................................................................................. 3 2.1.Objetivos generales ............................................................................................... 3 2.2.Objetivos específicos ............................................................................................ 3 3.Justificación ....................................................................................................... 4 4.Marco teórico ...................................................................................................... 4 5.Metodología y análisis ..................................................................................... 22 6.Conclusiones .................................................................................................... 32 2 1. Introducción A lo largo de mi carrera como músico estuve influenciado por ritmos populares de Colombia. Específicamente por el vallenato del cual aprendí y adquirí experiencia desde niño en los festivales vallenatos; eventos en los cuales se trata de rescatar la verdadera esencia de este género conformado por caja, guacharaca y acordeón. Siempre relacioné el vallenato con todas mis actividades musicales. La academia me dio -

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sitaram Asur, B.E., M.Sc. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Prof. Srinivasan Parthasarathy, Adviser Prof. Gagan Agrawal Adviser Prof. P. Sadayappan Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering c Copyright by Sitaram Asur 2009 ABSTRACT Data originating from many different real-world domains can be represented mean- ingfully as interaction networks. Examples abound, ranging from gene expression networks to social networks, and from the World Wide Web to protein-protein inter- action networks. The study of these complex networks can result in the discovery of meaningful patterns and can potentially afford insight into the structure, properties and behavior of these networks. Hence, there is a need to design suitable algorithms to extract or infer meaningful information from these networks. However, the challenges involved are daunting. First, most of these real-world networks have specific topological constraints that make the task of extracting useful patterns using traditional data mining techniques difficult. Additionally, these networks can be noisy (containing unreliable interac- tions), which makes the process of knowledge discovery difficult. Second, these net- works are usually dynamic in nature. Identifying the portions of the network that are changing, characterizing and modeling the evolution, and inferring or predict- ing future trends are critical challenges that need to be addressed in the context of understanding the evolutionary behavior of such networks. To address these challenges, we propose a framework of algorithms designed to detect, analyze and reason about the structure, behavior and evolution of real-world interaction networks. -

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions by Ned Hémard

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Shall We Dance Dancing has been an essential part of New Orleans’ psyche almost since its very beginning. Pierre François de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal replaced Bienville, the city’s founder, as Governor of Louisiana. He set the standards high with his polished manners, frequently sponsoring balls, dinners, and other elegant social soirées. Serving from 1743 to 1753, he even provided the colony with a Parisian dancing master named Baby. Below are numerous quotes through the ages about the Crescent City’s special love affair with dancing: There were balls, with court dress de rigueur, where gaily uniformed officers danced with bejeweled women. This was the beginning of fashionable life in the colony. - LYLE SAXON, writing of “de Vaudreuil’s régime” in Old Louisiana The eccentricities of Baby's mind, as well as those of his physical organization had made him famous in the colony, and the doleful mien with which he used to give his lessons, had gained him the appellation of the Don Quixote of dancing. -Louisiana Historian CHARLES GAYARRÉ on Baby, the Dancing Master The female Creoles being in general without education, can possess no taste for reading music or drawing, but they are passionately fond of dancing … passing whole nights in succession in this exercise. - PIERRE-LOUIS BERQUIN-DUVALLON, Travels in Louisiana and the Floridas in the Year 1802, Giving the Correct Picture of Those Countries It’s the land where they dance more than any other. - LOUIS-NARCISSE BAUDRY DES LOZIÈRES, Second Voyage à la Louisiane, 1803 Upon my arrival at New Orleans, I found the people very Solicitous to maintain their Public Ball establishment, and to convince them that the American Government felt no disposition to break in upon their amusements … - GOVERNOR W. -

Traversing Boundaries in Gottschalk's the Banjo

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Visual & Performing Arts Faculty Publications Visual & Performing Arts 5-2017 Porch and Playhouse, Parlor and Performance Hall: Traversing Boundaries in Gottschalk's The Banjo Laura Moore Pruett Merrimack College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/vpa_facpub Part of the Music Performance Commons This is a pre-publication author manuscript of the final, published article. Repository Citation Pruett, L. M. (2017). Porch and Playhouse, Parlor and Performance Hall: Traversing Boundaries in Gottschalk's The Banjo. Journal of the Society for American Music, 11(2), 155-183. Available at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/vpa_facpub/5 This Article - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Visual & Performing Arts at Merrimack ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Visual & Performing Arts Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Merrimack ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Porch and Playhouse, Parlor and Performance Hall: Traversing Boundaries in Gottschalk’s The Banjo LAURA MOORE PRUETT ABSTRACT This article reconsiders the cultural significance and historical impact of the well-known virtuosic piano composition The Banjo by Louis Moreau Gottschalk. Throughout the early nineteenth century, the banjo and the piano inhabited very specific and highly contrasting performance circumstances: black folk entertainment and minstrel shows for the former, white -

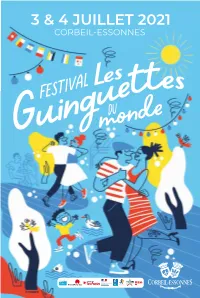

3 & 4 Juillet 2021

3 & 4 JUILLET 2021 CORBEIL-ESSONNES À L’ENTRÉE DU SITE, UNE FÊTE POPULAIRE POUR D’UNE RIVE À L’AUTRE… RE-ENCHANTER NOTRE TERRITOIRE Pourquoi des « guinguettes » ? à établir une relation de dignité Le 3 juillet Le 4 juillet Parce que Corbeil-Essonnes est une avec les personnes auxquelles nous 12h 11h30 ville de tradition populaire qui veut nous adressons. Rappelons ce que le rester. Parce que les guinguettes le mot culture signifie : « les codes, Parade le long Association des étaient des lieux de loisirs ouvriers les normes et les valeurs, les langues, des guinguettes originaires du Portugal situés en bord de rivière et que nous les arts et traditions par lesquels une avons cette chance incroyable d’être personne ou un groupe exprime SAMBATUC Bombos portugais son humanité et les significations Départ du marché, une ville traversée par la Seine et Batucada Bresilienne l’Essonne. qu’il donne à son existence et à son place du Comte Haymont développement ». Le travail culturel 15h Pourquoi « du Monde » ? vers l’entrée du site consiste d’abord à vouloir « faire Parce qu’à Corbeil-Essonnes, 93 Super Raï Band humanité ensemble ». le monde s’est donné rendez-vous, Maghreb brass band 12h & 13h30 108 nationalités s’y côtoient. Notre République se veut fraternelle. 16h15 Aquarela Nous pensons que cela est On ne peut concevoir une humanité une chance. fraternelle sans des personnes libres, Association des Batucada dignes et reconnues comme telles Alors pourquoi une fête des originaires du Portugal dans leur identité culturelle. 15h « guinguettes du monde » Bombos portugais Association Scène à Corbeil-Essonnes ? À travers cette manifestation, 18h Parce que c’est tellement bon de c’est le combat éthique de Et Sonne faire la fête. -

TRACEPLAY-PRESS-KIT-2017.Pdf

EDITOR “Our audience and urban creators were looking for a single platform that offers the best urban music and entertainment on all connected devices, all over the world. TracePlay is our answer to this request”. OLIVIER LAOUCHEZ CHAIRMAN, CEO AND CO-FOUNDER OF TRACE GROUP SUMMARY 1/ THE APP 03 TRACE PRESENTS TRACEPLAY 04 AN OFFER THAT FULLY INCLUDES URBAN MUSIC 2/ THE EXPERIENCE 05 LIVE TV: 9 TRACE MUSIC TV CHANNELS + 1 TV CHANNEL DEDICATED TO SPORT CELEBRITIES 06 LIVE RADIOS : 31 THEMATIC TRACE RADIOS 07 SVOD & ORIGINALS : OVER 2000 URBAN ASSETS 3/ THE OFFER 08 PRICES 09 DEVICES 10 GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION APPENDIX: TRACEPLAY PROGRAM CATALOGUE 2017 WWW.TRACEPLAY.TV 1/ THE APP 1.1 TRACE PRESENTS TRACEPLAY TracePlay is the first subscription-based service entirely dedicated to urban and afro-urban music and entertainment. The App is available worldwide on most THE BEST RADIOS connected devices and offers an instant Afro-urban series, movies, documentaries 30 radio channels covering the various urban and unlimited access to 10 live TV chan- and concerts. and afro-urban genres. nels, 30 live radios and more than 2000 on demand programs. LIVE TV EXPLORE Watch the 9 best urban and afro-urban music channels Browse by region, topic, genre or mood and the #1 sport celebrities channel to make your choice. ON DEMAND Instant access to more than 2000 selected programs including originals. TV | RADIO | DIGITAL | EVENTS | STUDIOS | MOBILE | MAGAZINE TRACEPLAY | PRESS KIT 2017 03 1/ THE APP 1.2 AN OFFER THAT FULLY INCLUDES URBAN MUSIC TracePlay leverages Trace’s 14 years expertise in music scheduling to offer a unique music experience: all Urban, African, Latin, Tropical and Gospel music genres are available and curated on a single App for the youth who is 100% connected. -

Shilliam, Robbie. "Dread Love: Reggae, Rastafari, Redemption." the Black Pacific: Anti- Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections

Shilliam, Robbie. "Dread Love: Reggae, RasTafari, Redemption." The Black Pacific: Anti- Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 109–130. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 23 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474218788.ch-006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 23 September 2021, 11:28 UTC. Copyright © Robbie Shilliam 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Dread Love: Reggae, RasTafari, Redemption Introduction Over the last 40 years roots reggae music has been the key medium for the dissemination of the RasTafari message from Jamaica to the world. Aotearoa NZ is no exception to this trend wherein the direct action message that Bob Marley preached to ‘get up stand up’ supported the radical engagements in the public sphere prompted by Black Power.1 In many ways, Marley’s message and demeanour vindicated the radical oppositional strategies that activists had deployed against the Babylon system in contradistinction to the Te Aute Old Boy tradition of tactful engagement. No surprise, then, that roots reggae was sometimes met with consternation by elders, although much of the issue revolved specifically around the smoking of Marijuana, the wisdom weed.2 Yet some activists and gang members paid closer attention to the trans- mission, through the music, of a faith cultivated in the Caribbean, which professed Ethiopia as the root and Haile Selassie I as the agent of redemption. And they decided to make it their faith too. -

The Dance in Place Congo. I. Congo Square

THE DANCE IN PLACE CONGO. I. CONGO SQUARE. HOEVER has been to New Orleans with eyes not totally abandoned to buying and selling will, of course, remember St. Louis Cathedral, looking south-eastward — riverward — across quaint Jackson Square, the old Place W d'Armes. And if he has any feeling for flowers, he has not forgotten the little garden behind the cathedral, so antique and unexpected, named for the beloved old priest Père Antoine. The old Rue Royale lies across the sleeping garden's foot. On the street's farther side another street lets away at right angles, north-westward, straight, and imperceptibly downward from the cathedral and garden toward the rear of the city. It is lined mostly with humble ground-floor-and-garret houses of stuccoed brick, their wooden doorsteps on the brick sidewalks. This is Orleans street, so named when the city was founded. Its rugged round-stone pavement is at times nearly as sunny and silent as the landward side of a coral reef. Thus for about half a mile; and then Rampart street, where the palisade wall of the town used to run in Spanish days, crosses it, and a public square just beyond draws a grateful canopy of oak and sycamore boughs. That is the place. One may shut his buff umbrella there, wipe the beading sweat from the brow, and fan himself with his hat. Many's the bull-fight has taken place on that spot Sunday afternoons of the old time. That is Congo Square. The trees are modern. So are the buildings about the four sides, for all their aged looks. -

Coopération Culturelle Caribéenne : Construire Une Coopération Autour Du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs Diné

Coopération culturelle caribéenne : construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs Diné To cite this version: Anaïs Diné. Coopération culturelle caribéenne : construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-01730691 HAL Id: dumas-01730691 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01730691 Submitted on 13 Mar 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Sous le sceau de l’Université Bretagne Loire Université Rennes 2 Equipe de recherche ERIMIT Master Langues, cultures étrangères et régionales Les Amériques – Parcours PESO Coopération culturelle caribéenne Construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs DINÉ Sous la direction de : Rodolphe ROBIN Septembre 2017 0 1 REMERCIEMENTS Je tiens à remercier toutes les personnes avec lesquelles j’ai pu échanger et qui m’ont aidé à la rédaction de ce mémoire. Je remercie tout d’abord mon directeur de recherches Rodolphe Robin pour m’avoir accompagné et soutenu depuis mes premières années à l’Université Rennes 2. Je remercie grandement l’Université Rennes 2 et l’Université de Puerto Rico (UPR) pour la formation et toutes les opportunités qu’elles m’ont offertes. -

African Drumming in Drum Circles by Robert J

African Drumming in Drum Circles By Robert J. Damm Although there is a clear distinction between African drum ensembles that learn a repertoire of traditional dance rhythms of West Africa and a drum circle that plays primarily freestyle, in-the-moment music, there are times when it might be valuable to share African drumming concepts in a drum circle. In his 2011 Percussive Notes article “Interactive Drumming: Using the power of rhythm to unite and inspire,” Kalani defined drum circles, drum ensembles, and drum classes. Drum circles are “improvisational experiences, aimed at having fun in an inclusive setting. They don’t require of the participants any specific musical knowledge or skills, and the music is co-created in the moment. The main idea is that anyone is free to join and express himself or herself in any way that positively contributes to the music.” By contrast, drum classes are “a means to learn musical skills. The goal is to develop one’s drumming skills in order to enhance one’s enjoyment and appreciation of music. Students often start with classes and then move on to join ensembles, thereby further developing their skills.” Drum ensembles are “often organized around specific musical genres, such as contemporary or folkloric music of a specific culture” (Kalani, p. 72). Robert Damm: It may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music for the sake of enhancing the musical skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience of the participants. PERCUSSIVE NOTES 8 JULY 2017 PERCUSSIVE NOTES 9 JULY 2017 cknowledging these distinctions, it may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music (culturally specific rhythms, processes, and concepts) for the sake of enhancing the musi- cal skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience Aof the participants in a drum circle. -

Créolité and Réunionese Maloya: from ‘In-Between’ to ‘Moorings’

Créolité and Réunionese Maloya: From ‘In-between’ to ‘Moorings’ Stephen Muecke, University of New South Wales An old Malbar is wandering in the countryside at night, and, seeing a light, approaches a cabin.1 It is open, so he goes in. He is invited to have a meal. No questions are asked; but he sings a ‘busted maloya’ [maloya kabosé] that speaks of his desire to open his wings and fly away, to accept the invitation to sleep in the cabin, to fall into the arms of the person narrating the ballad, and to weep. The whole company sings the ‘busted maloya.’2 Malbar is the name for Tamils descended from indentured labourers from parts of South India including the Malabar Coast and Pondicherry, where the French had another colony. Estimated to number 180,000, these diasporic Tamils had lost their language and taken up the local lingua franca, Creole, spoken among the Madagascans, French, Chinese and Africans making up the population of Réunion in the Indian Ocean. Creole, as a language and set of cultural forms, is not typical of many locations in the Indian Ocean. While the central islands of Mauritius, the Seychelles, Rodriguez, Agalega, Chagos and Réunion have their distinct varieties of French Creole language, Creole is not a concept that has currency in East Africa, Madagascar or South Asia. Versions of creolized English exist in Northern and Western Australia; at Roper River in the 1 Thanks to Elisabeth de Cambiaire and the anonymous reviewers of this paper for useful additions and comments, and to Françoise Vergès and Carpanin Marimoutou for making available the UNESCO Dossier de Candidature. -

Volume 24, Number 04 (April 1906) Winton J

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 4-1-1906 Volume 24, Number 04 (April 1906) Winton J. Baltzell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Baltzell, Winton J.. "Volume 24, Number 04 (April 1906)." , (1906). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/513 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APRIL, 1906 ISO PER YEAR ‘TF'TnTT^ PRICE 15 CENTS 180.5 THE ETUDE 209 MODERN SIX-HAND^ LU1T 1 I1 3 Instruction Books PIANO MUSIC “THE ETUDE” - April, 1906 Some Recent Publications Musical Life in New Orleans.. .Alice Graham 217 FOR. THE PIANOFORTE OF «OHE following ensemb Humor in Music. F.S.Law 218 IT styles, and are usi caching purposes t The American Composer. C. von Sternberg 219 CLAYTON F. SUMMY CO. _la- 1 „ net rtf th ’ standard foreign co Experiences of a Music Student in Germany in The following works for beginners at the piano are id some of the lat 1905...... Clarence V. Rawson 220 220 Wabash Avenue, Chicago.