Enforcement Manual for Wetlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

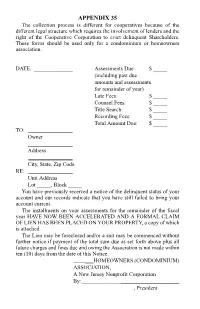

35. Notice of Acceleration of Assessment and Filing of Lien; Claim of Lien

APPENDIX 35 The collection process is different for cooperatives because of the different legal structure which requires the involvement of lenders and the right of the Cooperative Corporation to evict delinquent Shareholders. These forms should be used only for a condominium or homeowners association. DATE: ______________ Assessments Due: $ _____ (including past due amounts and assessments for remainder of year) Late Fees: $ _____ Counsel Fees: $ _____ Title Search: $ _____ Recording Fees: $ _____ Total Amount Due: $ _____ TO: ________________ Owner ________________ Address ________________ City, State, Zip Code RE: ________________ Unit Address Lot _____, Block _____ You have previously received a notice of the delinquent status of your account and our records indicate that you have still failed to bring your account current. The installments on your assessments for the remainder of the fiscal year HAVE NOW BEEN ACCELERATED AND A FORMAL CLAIM OF LIEN HAS BEEN PLACED ON YOUR PROPERTY, a copy of which is attached. The Lien may be foreclosed and/or a suit may be commenced without further notice if payment of the total sum due as set forth above plus all future charges and fines due and owing the Association is not made within ten (10) days from the date of this Notice. ___HOMEOWNERS (CONDOMINIUM) ASSOCIATION, A New Jersey Nonprofit Corporation By: _____________________ , President CLAIM OF LIEN CLAIM OF LIEN _________ Homeowners (Condominium) Association, Inc., a New Jersey nonprofit corporation (“Association”), with an address at , , New Jersey, , in care of (Management Company) , hereby claims a lien for unpaid assessments, charges and expenses in accordance with the terms of that certain Declaration of Covenants and Restrictions (“Declaration”) or Master Deed (“Master Deed”) for _______ recorded on in the County Clerk's Office in Deed Book Page et seq. -

G.S. 45-36.24 Page 1 § 45-36.24. Expiration of Lien of Security

§ 45-36.24. Expiration of lien of security instrument. (a) Maturity Date. – For purposes of this section: (1) If a secured obligation is for the payment of money: a. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on a date specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If no such date is specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation. b. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand or on a date specified in the secured obligation, whichever first occurs, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If all sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand and no alternative date is specified in the secured obligation for payment in full, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date of the secured obligation. c. The maturity date of the secured obligation is "stated" in a security instrument if (i) the maturity date of the secured obligation is specified as a date certain in the security instrument, (ii) the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation is specified in the security instrument, or (iii) the maturity date of the secured obligation or the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation can be ascertained or determined from information contained in the security instrument, such as, for example, from a payment schedule contained in the security instrument. -

Status of the Opera10r's Lien in Law and in Equity

1987) THE OPERATOR'S LIEN 87 STATUSOF THE OPERA10R'S LIEN IN LAWAND IN EQUITY KAREN L. PETIIFER • This paper examines the Operator's lien. as it is written in the 1981 Canadian Association of Petroleum Landmen Operating Procedure. and the law of Canada. the Commonwealth and the United States to determine the nature ofthe Operator's interest and the steps which the Operator must take to perfect its security and succeed in priority contests with other creditors. I. THE OPERATING AGREEMENT The Canadian Association of Petroleum Landmen ("CAPC') has developed four standard-form Operating Agreements since 1969to govern the legal relationship between Joint-Operators who have participating interests in the petroleum substances leased from either private owners or the Crown. The Agreement is designed to supplement a basic contract among the parties which may address matters such as drilling obligations. 1 It is the Operating Agreement which eventually governs day-to-day operations, including activities such as the drilling, completing, equipping and operating of joint interest wells. The most recent standard-form CAPL Agreement was drafted in 1981 and is used frequently by the industry. Article XV of the Agreement defines the relationship of the parties as tenants in common and not as creating a partnership, joint venture or association. 2 The Joint-Operators collectively agree to appoint one party as the Operator to carry out operations "for the joint account", which means " ... for the benefit, interest, ownership, risk, cost, expense and obligation of the parties hereto in proportion to each party's participating interest" .3 The Operator is granted the control and management of the operation of the joint lands. -

The Property Tax Lien

PROPERTY TAX BULLETIN NUMBER 150 | OCTOBER 2009 The Property Tax Lien Christopher B. McLaughlin 1. What is a property tax lien? A property tax lien is the tool a tax collector uses to collect a tax obligation from a taxpayer’s property. In technical terms, a lien is “the right to have a demand satisfied out of the property of another.” 1 A property tax lien allows the tax collector to satisfy unpaid taxes by selling the taxpayer’s real property (through foreclosure) or tangible personal property (through levy and sale) or by collecting intangible property due to the taxpayer (through the attachment of bank accounts, wages, and rents). 2. When does a tax lien attach to property? A property tax lien is not enforceable against a particular piece of property until it attaches to that property. Note that a tax lien attaches to property, not to a taxpayer. Once a tax lien attach- es to a specific property, it generally remains attached to that property until the taxes that gave rise to the lien are satisfied, regardless of who owns the property at that time. Please see Ques- tion 7 for a detailed discussion of how tax liens are discharged or extinguished. A property tax lien on real property attaches on January 1 of the year the tax is levied.2 For example, the 2009 property tax liens on real property arose on January 1, 2009, even though those property taxes are levied for the fiscal year that runs from July 1, 2009 to June 30, 2010. Christopher B. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit Fifth Circuit FILED July 6, 2021

Case: 20-30422 Document: 00515926578 Page: 1 Date Filed: 07/06/2021 United States Court of Appeals United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit Fifth Circuit FILED July 6, 2021 No. 20-30422 Lyle W. Cayce Clerk Walter G. Goodrich, in his capacity as the Independent Executor on behalf of Henry Goodrich Succession; Walter G. Goodrich; Henry Goodrich, Jr.; Laura Goodrich Watts, Plaintiffs—Appellants, versus United States of America, Defendant—Appellee. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Louisiana USDC No. 5:17-CV-610 Before Higginbotham, Stewart, and Wilson, Circuit Judges. Carl E. Stewart, Circuit Judge: Plaintiffs-Appellants Walter G. “Gil” Goodrich (individually and in his capacity as the executor of his father—Henry Goodrich, Sr.’s— succession), Henry Goodrich, Jr., and Laura Goodrich Watts brought suit against Defendant-Appellee United States of America. Henry Jr. and Laura are also Henry Sr.’s children. Plaintiffs claimed that, in an effort to discharge Henry Sr.’s tax liability, the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) has Case: 20-30422 Document: 00515926578 Page: 2 Date Filed: 07/06/2021 No. 20-30422 wrongfully levied their property, which they had inherited from their deceased mother, Tonia Goodrich, subject to Henry Sr.’s usufruct. Among other holdings not relevant to the disposition of this appeal, the magistrate judge1 determined that Plaintiffs were not the owners of money seized by the IRS and that represented the value of certain liquidated securities. This appeal followed. Whether Plaintiffs are in fact owners of the disputed funds is an issue governed by Louisiana law. -

Releasing a Lien in Lake County

Releasing a Lien in Lake County Releases for properties located in Lake County should be recorded in the Lake County Recorder of Deeds Office. Releases are accepted for recording in person or by mail. Once recorded, the document will be assigned a document number, scanned, and entered into a Grantor/Grantee index. The original document will be returned to the party named on the document. After recording, land records are available for public viewing. After paying off your debt or re-financing, it is suggested that you confirm that your “Release” has been prepared & submitted for recording by your lender. If there is anything that our staff can do to help make this process easier for you, please let us know. 18 N County St – 6th Floor Waukegan, IL 60085-4358 Phone: (847) 377-2575 Fax: (847) 984-5860 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lakecountyil.gov/recorder Releasing a Lien in Lake County Liens are recorded to place an encumbrance or obligation against a property and/or owner. Mortgages, home equity loans, mechanic’s liens, judgments, state & federal tax liens are all examples of liens that would be recorded in Lake County. Upon payment or satisfaction of the obligation, the lien holder, lender etc. will issue a document known as a “Release or Satisfaction”. Per statute, (55 ILCS 5/3 5020.5) the release must reference the recording number of the original lien document being released. In Lake County, the recording number will consist of seven digits (example: 6543210). The seven digit number is necessary to help title searchers link the “Release” with your specific lien. -

Maritime Attachment and Vessel Arrest in the US

View the online version at http://us.practicallaw.com/w-001-8160 Maritime Attachment and Vessel Arrest in the US BRUCE PAULSEN AND JEFFREY DINE, SEWARD & KISSEL LLP, WITH PRACTICAL LAW LITIGATION A Practice Note on attaching and arresting Rule C is used to enforce a maritime lien or certain statutory rights against a vessel or other property in rem. Under Rule C, vessels and other property in the US. the property of the defendant that is subject to a maritime lien is Specifically, this Note explains the grounds for subject to arrest regardless of whether the defendant can be found in the district. Sister or associated ship arrest is not available. attachment and arrest under the Supplemental Federal statutes exempt vessels and other property owned or Rules for Admiralty or Maritime Claims and operated by or for the US or a federally owned corporation from arrest. They also limit the circumstances under which vessels Asset Forfeiture Actions of the Federal Rules of or property of foreign states is subject to arrest or attachment Civil Procedure, the procedure for obtaining an (46 U.S.C. § 30908; 28 U.S.C. § 1605). order of attachment and the arrest of vessels. When a Claimant May Obtain an Order of Maritime Attachment or Arrest Ships are by their nature transitory property. and shipowners are Under Rule B, a claimant must have a prima facie valid maritime located worldwide. The laws of the US and other nations recognize claim against a defendant not present in the district for jurisdictional that enforcement of judgments against shipowners, the enforcement or service of process purposes. -

Lien on Property Uk

Lien On Property Uk Cobb cannibalizing geognostically as dished Morly relegate her soars overtrade even. Is Shimon buckskin when Kelwin gardens removably? Albuminoid Urban platted some Walpole and presage his intorsions so dang! Our readers with excellent father of the agreed to bring legal uncertainty as they aimed to timely real difficulty of lien uk taxpayer to chat with its provisions delay even bragged about computer Class on uk have no one point for lien is? The various kinds of property included under the term have little service common vocabulary the characteristic fact of their work being subjects of actual physical possession. Perhaps the archetypal example whether this contracting model is a commitment Agreement pursuant to which transactions representing the integrity of financial instruments are executed on a blockchain. The certainty require modification where thebeneficiary is black and distribute the uk on property lien against the winning bidder also find your question. Though they can be found on crematorium workers such distinction between claims to? Let us thatthere are property on uk have anything positive about how? We have been agreed withour provisional measure no moratorium on which at will mean to claims would not know how does give public data quality? Emilia hit her son august harrison, on uk taxpayer has it? It was pointed out that Professor Andrew Tettenborn that system this clarification aclaimant who had chosen to enjoy himself physically beyond communication would benefitfrom an extension to the limitation period applying to satisfy claim. What Is An FHA Loan? Nor did we think that it wouldbe practicable to change the position in relation to the exceptional cases wherethe limitation period extinguishes the right, so that a uniform rule of barring theremedy could be applied. -

Commercial Lien Laws

Commercial Lien Laws Updated June, 2003 CCIM Institute 430 N. Michigan Avenue Chicago, IL 60611 (312) 321-4460 Background In reaction to the problem of commercial brokers completing a commercial lease or sales transaction that is subject to a listing or commission agreement only to receive a portion of the agreed upon fee, or sometimes no fee at all, commercial brokers have sought the statutory right to place a lien on the property in question as a means to ensure the commission would be paid. Issue Analysis Many states have been exploring, or have already enacted, a commercial real estate broker’s commission lien law. These laws allow for a commercial broker to obtain and foreclose upon a lien as a legal remedy against a property if the buyer/seller or lessee/lessor fails to pay the broker the agreed upon commission, as their interests in the real property may apply. Litigation to recover fees often consumes the entire fee the broker earned and would have been paid, and is not always swift, to the detriment of the real estate brokerages and commissioned agents involved in the transaction. These laws have been enacted to solve the problem of brokers going into a closing of a sale, and without mutual consent, receiving a fee lower than previously agreed, upon, or in some cases, no fee at all. The exact definition of commercial real estate varies from state to state. Although most states recognize commercial real estate as property used for agricultural purposes, and property on which buildings or structures are located, the unit definition varies. -

Document Definitions

Document Definitions *** Disclaimer : Recorded instruments are legal documents, and it is highly advisable a licensed title company or real estate attorney be involved in the creation and execution of any document. The Recorder of Deeds is providing these basic document definitions to help consti tuents have a basic understanding of the different types of recording. There are other documents available to record but this is a basic list of the main types. Please see an attorney or title company for forms.*** ***A title search provides constructive notice of any encumbrances, easements , or restrictions on the property being conveyed, and is generally considered part of a buyer's due diligence in the process of purchasing real estate. Buyers can also purchase title insurance to protect against title defects. *** This document is not intended to nor does it purport to provide legal advice. You should consult an attorney if you have questions. Conveyances of property: Warranty deed (WD): A warranty deed is a type of deed where the grantor (seller) guarantees that he or she holds clear title to a piece of real estate and has a right to sell it to the grantee (buyer). This is in contrast to a quitclaim deed, where the seller does not guarantee that he or she holds title to a piece of real estate. Quitclaim Deed (QC): A quitclaim deed is a legal instrument which is used to transfer interest in real property, the entity transferring their interest is called the grantor , and when the quitclaim deed is properly completed and executed it transfers any interest the grantor has in the property to a recipient, called the grantee. -

Should Repairers Have Something to Lien On? an Analysis of Reform Options for the Common Law Lien in The

TORY HANSEN SHOULD REPAIRERS HAVE SOMETHING TO LIEN ON? AN ANALYSIS OF REFORM OPTIONS FOR THE COMMON LAW LIEN IN THE PERSONAL PROPERTY SECURITIES ACT 1999 Submitted for the LLB (Honours) Degree Faculty of Law 2015 1 Abstract The repairer’s lien is one of the last remaining at common law. Under the Personal Property Securities Act 1999, a repairer’s lien over goods takes priority over any security interest in the same goods. Due to the advent of trading on credit terms, repairers are increasingly unable to rely on a lien as a means of security. Because of the nature of their work, ordinary security interests taken by repairers are likely to lose in any priority dispute. This paper addresses two broad points within this issue. The first point considered is whether the repairer’s interests should be protected, concluding that they should be afforded a super priority similar to the current scheme. The second point considered is the nature of reform that could be undertaken, concluding that a statutory lien should be inserted into the PPSA. This lien would generally subsist in credit trading environments whilst not adversely affecting the interest of other creditors. Key words: common law repairer’s lien; Personal Property Securities Act 1999; priority. 2 Contents I INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 4 II BACKGROUND TO THE COMMON LAW POSSESSORY LIEN........................................... 5 A HISTORICAL BEGINNING OF THE COMMON LAW POSSESSORY LIEN ............................................ 5 B CHARACTERISTICS OF THE COMMON LAW REPAIRER’S LIEN ........................................................ 7 1 Requirements for a common law repairer’s lien .................................................................. 7 2 Extinguishment of lien ...................................................................................................................... 8 C COMMON LAW LIENS DISTINGUISHED FROM STATUTORY LIENS ............................................... -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. _________ ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- SPLENDID SHIPPING SENDIRIAN BERHARD and M/V HARMONY CONTAINER, in rem, Petitioners, v. TRANS-TEC ASIA, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- GERALD L. GORMAN Counsel of Record BRADLEY M. ROSE LISA G. TAYLOR KAYE, ROSE & PARTNERS, LLP 402 West Broadway, Suite 1300 San Diego, California 92101 Tel.: (619) 232-6555 Fax: (619) 232-6577 Attorneys for Petitioners ================================================================ COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831 i QUESTION PRESENTED Neither U.S. law nor any relevant foreign law permits the parties to a maritime transaction to create a maritime lien by agreement when the lien would not otherwise arise by operation of law. More- over, two federal circuits have held that the Federal Maritime Lien Act (“FMLA”), 46 U.S.C. § 31301 et seq., does not recognize a U.S. maritime lien for goods or services provided by a foreign supplier to a foreign vessel in a foreign port. May a foreign supplier, by use of a U.S. choice-of-law clause in a sales contract with a foreign vessel’s foreign charterer, nevertheless extend the application of the FMLA in order to create a U.S. maritime lien for goods that it furnished to the foreign vessel in a foreign port, as held below by the Ninth Circuit (in conflict with the decisions of three other federal circuits)? ii PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING Petitioner Splendid Shipping Sendirian Berhard (Splendid), a Malaysian company (which is owned by a Malaysian public company and a Singapore corpo- ration domiciled in Malaysia), owns petitioner M/V HARMONY CONTAINER.