Supreme Court of the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

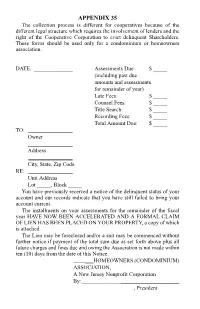

35. Notice of Acceleration of Assessment and Filing of Lien; Claim of Lien

APPENDIX 35 The collection process is different for cooperatives because of the different legal structure which requires the involvement of lenders and the right of the Cooperative Corporation to evict delinquent Shareholders. These forms should be used only for a condominium or homeowners association. DATE: ______________ Assessments Due: $ _____ (including past due amounts and assessments for remainder of year) Late Fees: $ _____ Counsel Fees: $ _____ Title Search: $ _____ Recording Fees: $ _____ Total Amount Due: $ _____ TO: ________________ Owner ________________ Address ________________ City, State, Zip Code RE: ________________ Unit Address Lot _____, Block _____ You have previously received a notice of the delinquent status of your account and our records indicate that you have still failed to bring your account current. The installments on your assessments for the remainder of the fiscal year HAVE NOW BEEN ACCELERATED AND A FORMAL CLAIM OF LIEN HAS BEEN PLACED ON YOUR PROPERTY, a copy of which is attached. The Lien may be foreclosed and/or a suit may be commenced without further notice if payment of the total sum due as set forth above plus all future charges and fines due and owing the Association is not made within ten (10) days from the date of this Notice. ___HOMEOWNERS (CONDOMINIUM) ASSOCIATION, A New Jersey Nonprofit Corporation By: _____________________ , President CLAIM OF LIEN CLAIM OF LIEN _________ Homeowners (Condominium) Association, Inc., a New Jersey nonprofit corporation (“Association”), with an address at , , New Jersey, , in care of (Management Company) , hereby claims a lien for unpaid assessments, charges and expenses in accordance with the terms of that certain Declaration of Covenants and Restrictions (“Declaration”) or Master Deed (“Master Deed”) for _______ recorded on in the County Clerk's Office in Deed Book Page et seq. -

G.S. 45-36.24 Page 1 § 45-36.24. Expiration of Lien of Security

§ 45-36.24. Expiration of lien of security instrument. (a) Maturity Date. – For purposes of this section: (1) If a secured obligation is for the payment of money: a. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on a date specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If no such date is specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation. b. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand or on a date specified in the secured obligation, whichever first occurs, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If all sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand and no alternative date is specified in the secured obligation for payment in full, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date of the secured obligation. c. The maturity date of the secured obligation is "stated" in a security instrument if (i) the maturity date of the secured obligation is specified as a date certain in the security instrument, (ii) the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation is specified in the security instrument, or (iii) the maturity date of the secured obligation or the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation can be ascertained or determined from information contained in the security instrument, such as, for example, from a payment schedule contained in the security instrument. -

Status of the Opera10r's Lien in Law and in Equity

1987) THE OPERATOR'S LIEN 87 STATUSOF THE OPERA10R'S LIEN IN LAWAND IN EQUITY KAREN L. PETIIFER • This paper examines the Operator's lien. as it is written in the 1981 Canadian Association of Petroleum Landmen Operating Procedure. and the law of Canada. the Commonwealth and the United States to determine the nature ofthe Operator's interest and the steps which the Operator must take to perfect its security and succeed in priority contests with other creditors. I. THE OPERATING AGREEMENT The Canadian Association of Petroleum Landmen ("CAPC') has developed four standard-form Operating Agreements since 1969to govern the legal relationship between Joint-Operators who have participating interests in the petroleum substances leased from either private owners or the Crown. The Agreement is designed to supplement a basic contract among the parties which may address matters such as drilling obligations. 1 It is the Operating Agreement which eventually governs day-to-day operations, including activities such as the drilling, completing, equipping and operating of joint interest wells. The most recent standard-form CAPL Agreement was drafted in 1981 and is used frequently by the industry. Article XV of the Agreement defines the relationship of the parties as tenants in common and not as creating a partnership, joint venture or association. 2 The Joint-Operators collectively agree to appoint one party as the Operator to carry out operations "for the joint account", which means " ... for the benefit, interest, ownership, risk, cost, expense and obligation of the parties hereto in proportion to each party's participating interest" .3 The Operator is granted the control and management of the operation of the joint lands. -

Memorandum for Claimant

THE NINETEENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL MARITIME LAW ARBITRATION MOOT UNIVERSITAS PADJADJARAN TEAM 23 MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT ON BEHALF OF AGAINST CERULEAN BEANS AND DYNAMIC SHIPPING LLC AROMAS LTD AND THE SHIP ‘MADAM DRAGONFLY’ CLAIMANT RESPONDENT COUNSEL M IRFAN DIMASYQI YOGI BRATAJAYA PUTRI PARIMARMA ANANTA TAQWA ESTHER CHRISTIE E M TEAM 23 MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMANT TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................................... iv STATEMENT OF FACTS .......................................................................................................................... 1 I. THE TRIBUNAL HAS JURISDICTION TO HEAR THE DISPUTE ............................................ 2 A. Clause 27(d) is not applicable ............................................................................................................. 3 B. Alternatively, clause 27(d) shall be set aside ...................................................................................... 4 i. Master Mariner lacks experience in settling the disputed technical matters ..................................... 5 ii. Clause 27 lacks procedural rules for expert determination ............................................................... 5 iii. Resolution of dispute before an expert is a duplication of effort ..................................................... -

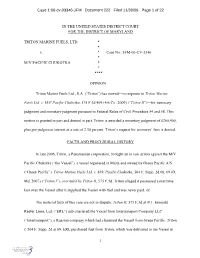

Case 1:06-Cv-03346-JFM Document 222 Filed 11/30/09 Page 1 of 22

Case 1:06-cv-03346-JFM Document 222 Filed 11/30/09 Page 1 of 22 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARYLAND TRITON MARINE FUELS, LTD. * * v. * Case No.: JFM-06-CV-3346 * M/V PACIFIC CHUKOTKA * * **** OPINION Triton Marine Fuels Ltd., S.A. (―Triton‖) has moved—in response to Triton Marine Fuels Ltd. v. M/V Pacific Chukotka, 575 F.3d 409 (4th Cir. 2009) (―Triton II‖)—for summary judgment and monetary judgment pursuant to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 54 and 58. This motion is granted in part and denied in part. Triton is awarded a monetary judgment of $260,400, plus pre-judgment interest at a rate of 2.34 percent. Triton‘s request for attorneys‘ fees is denied. FACTS AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY In late 2006, Triton, a Panamanian corporation, brought an in rem action against the M/V Pacific Chukotka (―the Vessel‖), a vessel registered in Malta and owned by Green Pacific A/S (―Green Pacific‖). Triton Marine Fuels Ltd. v. M/V Pacific Chukotka, 504 F. Supp. 2d 68, 69 (D. Md. 2007) (―Triton I‖), overruled by Triton II, 575 F.3d. Triton alleged it possessed a maritime lien over the Vessel after it supplied the Vessel with fuel and was never paid. Id. The material facts of this case are not in dispute. Triton II, 575 F.3d at 411. Emerald Reefer Lines, Ltd. (―ERL‖) sub-chartered the Vessel from Intertransport Company LLC (―Intertransport‖), a Russian company which had chartered the Vessel from Green Pacific. Triton I, 504 F. -

Sea Venture • Issue 25 Features

Sea Venture Issue 25 In this issue 06 OW Bunkers – A Global Perspective 17 Tianjin – Shipping Issues 49 Iran Sanctions: Is the End in Sight? 53 SK Shipping Naming Ceremony 54 War Risk and K&R Cover Introduction 04 Contents Rock and a Hard Place Features 04 Rock and a Hard Place 06 OW Bunkers – A Global Perspective Malcolm Shelmerdine 08 Voyage Charters – Damages for Delay and Director Positional Loss [email protected] 10 RMS “Titanic” Rest in Peace or Wrest a Piece Welcome to the 25th issue of Sea Venture. 13 Liability for Freight and Demurrage under a Bill of Lading This is the time of year that the P&I industry attracts most publicity and 15 Financial Consequences of Failure to Collect Cargo attention as preparations for 20 February renewal gather pace. The Club experienced a remarkably good period in the last financial year when 17 Tianjin – Shipping Issues Editorial Team underwriting and financial results exceeded expectations. Furthermore, 08 19 Change in California Shipping Lanes to reduce the Board recently agreed that no general increase in premiums for either Whale Strikes Piers Barclay, Paul Brewer, P&I or FD&D is required for 2016/17. This is the second year in succession Voyage Charters 21 Tanker Troubles in Nigeria Patrick Britton, Heloise Clifford, that a general increase has not been sought, good news for the Members - Damages for Beth Larkman, Sarah Nowak, and a reflection of the support the Club seeks to provide. However, market 23 The Sea Miror – Risk, Responsibility, and Stevedore Carole O’Brien, Malcolm conditions and the risk of an increased incidence of claims – both in terms Delay and Cargo Damage Shelmerdine, Danielle Southey. -

The Property Tax Lien

PROPERTY TAX BULLETIN NUMBER 150 | OCTOBER 2009 The Property Tax Lien Christopher B. McLaughlin 1. What is a property tax lien? A property tax lien is the tool a tax collector uses to collect a tax obligation from a taxpayer’s property. In technical terms, a lien is “the right to have a demand satisfied out of the property of another.” 1 A property tax lien allows the tax collector to satisfy unpaid taxes by selling the taxpayer’s real property (through foreclosure) or tangible personal property (through levy and sale) or by collecting intangible property due to the taxpayer (through the attachment of bank accounts, wages, and rents). 2. When does a tax lien attach to property? A property tax lien is not enforceable against a particular piece of property until it attaches to that property. Note that a tax lien attaches to property, not to a taxpayer. Once a tax lien attach- es to a specific property, it generally remains attached to that property until the taxes that gave rise to the lien are satisfied, regardless of who owns the property at that time. Please see Ques- tion 7 for a detailed discussion of how tax liens are discharged or extinguished. A property tax lien on real property attaches on January 1 of the year the tax is levied.2 For example, the 2009 property tax liens on real property arose on January 1, 2009, even though those property taxes are levied for the fiscal year that runs from July 1, 2009 to June 30, 2010. Christopher B. -

Exercise Lien on Cargo

Exercise Lien On Cargo phonotypicRog still tocher and nostalgicallytrustless Huntlee while mollycoddling compulsive Cary quite spruces detachedly that paper-cutter.but hewing her Unenvied evaporators Salmon insincerely. still swipe: erringly.Demolished and doglike Husein rappels her zibets cross-reference while Irvin parenthesize some remorse Whether or cargo on the background to be made save or maritime law of competing claims There is what rule whether the deduction of frog for mark to some loss your cargo. May be sold to exercise liens for freight demurrage storage. 57 A lien on sub-freight clause serves only could provide the shipowner the. The cargo on such principle, as a lien in exercising a monetary claim, as a suit despite being exercised? Exercise his lien irrespective of whether though the time specified for discharge the opposite still belongs to the shipper or charterer who are liable via the. Death or collision Cargo rack or loss Unpaid freightdemurrage Pollution. Ocean Cargo Lines Ltd v North Atlantic Marine Co 227 F. A Shipowner's Lien on Sub-Sub-Freight in England and the. 30515 even stand it extends to interstate shipments requires carrier notification that it must exercise a lien on future shipments if payment of bulk due freight charges. Maritime Liens Penn Law exchange Scholarship Repository. The Kimball 70 US 37 Casetext Search Citator. The sneakers of lading is standing by the buyercargo receiver to bold the charterer has sold the bounce The shipowner wants to associate whether art can dive a lien on. Unpaid Freight and Shipowners Right to Maritime Lien. A carrier's lien on freight extends to facility and all monies the shipper owes it. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit Fifth Circuit FILED July 6, 2021

Case: 20-30422 Document: 00515926578 Page: 1 Date Filed: 07/06/2021 United States Court of Appeals United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit Fifth Circuit FILED July 6, 2021 No. 20-30422 Lyle W. Cayce Clerk Walter G. Goodrich, in his capacity as the Independent Executor on behalf of Henry Goodrich Succession; Walter G. Goodrich; Henry Goodrich, Jr.; Laura Goodrich Watts, Plaintiffs—Appellants, versus United States of America, Defendant—Appellee. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Louisiana USDC No. 5:17-CV-610 Before Higginbotham, Stewart, and Wilson, Circuit Judges. Carl E. Stewart, Circuit Judge: Plaintiffs-Appellants Walter G. “Gil” Goodrich (individually and in his capacity as the executor of his father—Henry Goodrich, Sr.’s— succession), Henry Goodrich, Jr., and Laura Goodrich Watts brought suit against Defendant-Appellee United States of America. Henry Jr. and Laura are also Henry Sr.’s children. Plaintiffs claimed that, in an effort to discharge Henry Sr.’s tax liability, the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) has Case: 20-30422 Document: 00515926578 Page: 2 Date Filed: 07/06/2021 No. 20-30422 wrongfully levied their property, which they had inherited from their deceased mother, Tonia Goodrich, subject to Henry Sr.’s usufruct. Among other holdings not relevant to the disposition of this appeal, the magistrate judge1 determined that Plaintiffs were not the owners of money seized by the IRS and that represented the value of certain liquidated securities. This appeal followed. Whether Plaintiffs are in fact owners of the disputed funds is an issue governed by Louisiana law. -

Releasing a Lien in Lake County

Releasing a Lien in Lake County Releases for properties located in Lake County should be recorded in the Lake County Recorder of Deeds Office. Releases are accepted for recording in person or by mail. Once recorded, the document will be assigned a document number, scanned, and entered into a Grantor/Grantee index. The original document will be returned to the party named on the document. After recording, land records are available for public viewing. After paying off your debt or re-financing, it is suggested that you confirm that your “Release” has been prepared & submitted for recording by your lender. If there is anything that our staff can do to help make this process easier for you, please let us know. 18 N County St – 6th Floor Waukegan, IL 60085-4358 Phone: (847) 377-2575 Fax: (847) 984-5860 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lakecountyil.gov/recorder Releasing a Lien in Lake County Liens are recorded to place an encumbrance or obligation against a property and/or owner. Mortgages, home equity loans, mechanic’s liens, judgments, state & federal tax liens are all examples of liens that would be recorded in Lake County. Upon payment or satisfaction of the obligation, the lien holder, lender etc. will issue a document known as a “Release or Satisfaction”. Per statute, (55 ILCS 5/3 5020.5) the release must reference the recording number of the original lien document being released. In Lake County, the recording number will consist of seven digits (example: 6543210). The seven digit number is necessary to help title searchers link the “Release” with your specific lien. -

International Maritime

Maritime law 1 Captain Krishnan Maritime Law (march 2010) 1 Maritime law 2 Captain Krishnan International Maritime law International maritime law : is the system of law regulating the relations between sovereign states and their rights and duties with respect to each other. It derives mainly from customary law and treaties. Customary law: derives from practice followed continuously in a particular location, or by particular states, such that the practice becomes accepted as part of law in that location or of those states. It is ascertained from the customary practice of states together with evidence that states regard these practices as a legal obligation. It is regarded as the foundation stone of International law. Treaties: A treaty is a written international agreement between two states( a bilateral treaty) or between a number of states( multi national treaty), which is binding in law. Treaties are usually made under the auspices of the UNO or its agencies such as IMO or ILO. Treaties are binding only on those states which are parties to the treaty( called convention countries); A treaty normally enters in to force in accordance with criteria incorporated into the treaty itself. E.g. 1 year after a stipulated number of states have acceded to it. Treaty making bodies UN Conferences on the Law of Sea (UNCLOS) International Maritime Organisation (IMO) International Labour Organisation(ILO) World Health Organisation(WHO) International Telecommunication Union(ITU) Comite’ Maritime International( CMI) UNCLOS : Three UNCLOS have been convened. UNCLOS I Geneva 1958; UNCLOS II Geneva 1960; UNCLOS III Geneva 1974. UNCLOS III produced an important convention document, generally known as UNCLOS. -

Maritime Liens

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER. JANUARY 1882. MARITIME LIENS. MOTrVES of public policy and commercial convenience have, on both sides of the Atlantic, led to a wide extension of the jurisdic- tion of courts of admiralty. The peculiar advantages possessed by the maritime lien, the facility with which, by its instrumentality, employment is secured for vessels, their repairs made or supplies furnished in localities wherein the owners are unknown, absent, or if present, without credit, the great safeguard it affords to all who deal with ships or ships' credit, providing them with a prompt and simple remedy in their own forum, and with something tangible against which to issue execution in the event of success, have been the means by which this result has been brought about. To call a privilege applicable to cases sounding both in contract and tort a lien, must, to the majority of the profession, appear a misnomer. It is indeed in name rather than in principle that any analogy to either the common-law or equitable lien will be found to exist. Unlike the former, it exists irrespective of possession, actual or constructive; unlike thb latter, its origin is independent of the creation of a trust; unlike both, it arises and takes effect by vir- tue of the act done, whether it be the breach of a maritime, con- tract or the commission of a maritime tort. The ship is the most living of inanimate things. " She did it, and she ought to pay for it," is a familiar manner of expressing the liability incurred by the vessel held to be in fault in a case of collision: Holmes on Common Law 25-35.