Status of the Opera10r's Lien in Law and in Equity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

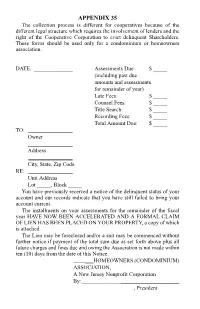

35. Notice of Acceleration of Assessment and Filing of Lien; Claim of Lien

APPENDIX 35 The collection process is different for cooperatives because of the different legal structure which requires the involvement of lenders and the right of the Cooperative Corporation to evict delinquent Shareholders. These forms should be used only for a condominium or homeowners association. DATE: ______________ Assessments Due: $ _____ (including past due amounts and assessments for remainder of year) Late Fees: $ _____ Counsel Fees: $ _____ Title Search: $ _____ Recording Fees: $ _____ Total Amount Due: $ _____ TO: ________________ Owner ________________ Address ________________ City, State, Zip Code RE: ________________ Unit Address Lot _____, Block _____ You have previously received a notice of the delinquent status of your account and our records indicate that you have still failed to bring your account current. The installments on your assessments for the remainder of the fiscal year HAVE NOW BEEN ACCELERATED AND A FORMAL CLAIM OF LIEN HAS BEEN PLACED ON YOUR PROPERTY, a copy of which is attached. The Lien may be foreclosed and/or a suit may be commenced without further notice if payment of the total sum due as set forth above plus all future charges and fines due and owing the Association is not made within ten (10) days from the date of this Notice. ___HOMEOWNERS (CONDOMINIUM) ASSOCIATION, A New Jersey Nonprofit Corporation By: _____________________ , President CLAIM OF LIEN CLAIM OF LIEN _________ Homeowners (Condominium) Association, Inc., a New Jersey nonprofit corporation (“Association”), with an address at , , New Jersey, , in care of (Management Company) , hereby claims a lien for unpaid assessments, charges and expenses in accordance with the terms of that certain Declaration of Covenants and Restrictions (“Declaration”) or Master Deed (“Master Deed”) for _______ recorded on in the County Clerk's Office in Deed Book Page et seq. -

G.S. 45-36.24 Page 1 § 45-36.24. Expiration of Lien of Security

§ 45-36.24. Expiration of lien of security instrument. (a) Maturity Date. – For purposes of this section: (1) If a secured obligation is for the payment of money: a. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on a date specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If no such date is specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation. b. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand or on a date specified in the secured obligation, whichever first occurs, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If all sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand and no alternative date is specified in the secured obligation for payment in full, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date of the secured obligation. c. The maturity date of the secured obligation is "stated" in a security instrument if (i) the maturity date of the secured obligation is specified as a date certain in the security instrument, (ii) the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation is specified in the security instrument, or (iii) the maturity date of the secured obligation or the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation can be ascertained or determined from information contained in the security instrument, such as, for example, from a payment schedule contained in the security instrument. -

Requirements of Timely Performance in Time and Voyage Charterparties

Graduate School REQUIREMENTS OF TIMELY PERFORMANCE IN TIME AND VOYAGE CHARTERPARTIES - AN EXPLORATION OF THEIR IDENTITY, SCOPE AND LIMITATIONS UNDER ENGLISH LAW Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Tamaraudoubra Tom Egbe School of Law University of Leicester 2019 Abstract REQUIREMENTS OF TIMELY PERFORMANCE IN TIME AND VOYAGE CHARTERPARTIES - AN EXPLORATION OF THEIR IDENTITY, SCOPE AND LIMITATIONS UNDER ENGLISH LAW By Tamaraudoubra Tom Egbe The importance of time in the performance of contractual obligations under sea carriage of goods arrangements are until now little explored. For the avoidance of breach, certain obligations and responsibilities of the parties to the contract need to be performed promptly. Ocean transport is an expensive venture and a shipowner could suffer considerable financial losses if an unnecessary but serious delay interrupt the vessel’s earning power in the course of the charterer’s performance of his contractual obligation. On the other hand, a charterer could also incur a substantial loss if arrangements for the shipment and receipt of cargo fail to go according to plan as a result of the shipowner’s failure to perform his charterparty obligation timely and with reasonable diligence. With these considerations in mind, this thesis critically explores the concept of timely performance in the discharge of the contractual obligations of parties to a contract of carriage. While the thesis is not an expository of the occurrence of time in all the obligations of parties to the carriage contract, it focusses particularly on the identity, scope, and limitations of timeliness in the context of timely payment of hire, laytime and reasonable despatch. -

Contracts Course

Contracts A Contract A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties with mutual obligations. The remedy at law for breach of contract is "damages" or monetary compensation. In equity, the remedy can be specific performance of the contract or an injunction. Both remedies award the damaged party the "benefit of the bargain" or expectation damages, which are greater than mere reliance damages, as in promissory estoppels. Origin and Scope Contract law is based on the principle expressed in the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda, which is usually translated "agreements to be kept" but more literally means, "pacts must be kept". Contract law can be classified, as is habitual in civil law systems, as part of a general law of obligations, along with tort, unjust enrichment, and restitution. As a means of economic ordering, contract relies on the notion of consensual exchange and has been extensively discussed in broader economic, sociological, and anthropological terms. In American English, the term extends beyond the legal meaning to encompass a broader category of agreements. Such jurisdictions usually retain a high degree of freedom of contract, with parties largely at liberty to set their own terms. This is in contrast to the civil law, which typically applies certain overarching principles to disputes arising out of contract, as in the French Civil Code. However, contract is a form of economic ordering common throughout the world, and different rules apply in jurisdictions applying civil law (derived from Roman law principles), Islamic law, socialist legal systems, and customary or local law. 2014 All Star Training, Inc. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. _________ ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- BULK JULIANA LTD. and M/V BULK JULIANA, her engines, tackle, apparel, etc., in rem, Petitioners, versus WORLD FUEL SERVICES (SINGAPORE) PTE LTD., Respondent. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI --------------------------------- --------------------------------- PETER B. SLOSS Counsel of Record [email protected] ROBERT H. MURPHY [email protected] DONALD R. WING [email protected] MURPHY, ROGERS, SLOSS, GAMBEL & TOMPKINS, APLC 701 Poydras Street, Suite 400 New Orleans, Louisiana 70139 Telephone: (504) 523-0400 Attorneys for Claimant-Petitioner, Bulk Juliana Ltd., appearing solely as the Owner and Claimant of the M/V BULK JULIANA ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i QUESTIONS PRESENTED This petition presents the following unsettled questions of federal maritime law, which are of wide- spread commercial importance to the global shipping community and should be resolved by this Court: 1. Under U.S. law, a maritime necessaries lien arises solely by operation of law and cannot be created by con- tract. Here, a Singapore fuel supplier claims -

The Law of Property

THE LAW OF PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL READINGS Class 14 Professor Robert T. Farley, JD/LLM PROPERTY KEYED TO DUKEMINIER/KRIER/ALEXANDER/SCHILL SIXTH EDITION Calvin Massey Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law The Emanuel Lo,w Outlines Series /\SPEN PUBLISHERS 76 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 http://lawschool.aspenpublishers.com 29 CHAPTER 2 FREEHOLD ESTATES ChapterScope ------------------- This chapter examines the freehold estates - the various ways in which people can own land. Here are the most important points in this chapter. ■ The various freehold estates are contemporary adaptations of medieval ideas about land owner ship. Past notions, even when no longer relevant, persist but ought not do so. ■ Estates are rights to present possession of land. An estate in land is a legal construct, something apart fromthe land itself. Estates are abstract, figments of our legal imagination; land is real and tangible. An estate can, and does, travel from person to person, or change its nature or duration, while the landjust sits there, spinning calmly through space. ■ The fee simple absolute is the most important estate. The feesimple absolute is what we normally think of when we think of ownership. A fee simple absolute is capable of enduringforever though, obviously, no single owner of it will last so long. ■ Other estates endure for a lesser time than forever; they are either capable of expiring sooner or will definitely do so. ■ The life estate is a right to possession forthe life of some living person, usually (but not always) the owner of the life estate. It is sure to expire because none of us lives forever. -

Bills of Lading Vs Sea Waybills, and the Himalaya Clause Peter G

Bills of Lading vs Sea Waybills, and The Himalaya Clause Peter G. Pamel and Robert C. Wilkins Borden Ladner Gervais, LLP Presented at the NJI/CMLA, Federal Court and Federal Court of Appeal Canadian Maritime Law Association Seminar April 15, 2011 Fairmont Château Laurier, Ottawa 1) Introduction Bills of lading and sea waybills are two of the most common forms of transport document used in contemporary shipping. Their similarities and difference, and respective uses, in such trade should be clearly understood by all who are involved in that activity. In particular the meaning of “document of title” used in respect of bills of lading, and whether sea waybills are or are not also such documents of title, have given rise to much debate, which has now largely been resolved in major shipping nations. Also, the impact on these transport documents of compulsorily applicable liability regimes set out in international carriage of goods by sea conventions is also essential to a proper grasp of the role these documents play in international maritime commerce. It is also interesting to examine how parties other than carriers, shippers and consignees can and do benefit from certain clauses in ocean bills of lading and sea waybills which purport to confer on such third parties or classes of them the exemptions from, and limitations of, liability which marine carriers assume in the performance of their functions. This paper will attempt to provide an overview of these issues, with special reference to how they are addressed in Canadian maritime law. 2) Bills of Lading and Sea Waybills in Modern Shipping Bills of lading and sea waybills are the two basic documents that attest to the carriage of goods by water, both domestically within Canada and internationally. -

Anatomy of a Will

PRESENTED AT 18th Annual Estate Planning, Guardianship and Elder Law Conference August 11‐12, 2016 Galveston, Texas ANATOMY OF A WILL Bernard E. ("Barney") Jones Author Contact Information: Bernard E. ("Barney") Jones Attorney at Law 3555 Timmons Lane, Suite 1020 Houston, Texas 77027 713‐621‐3330 Fax 713‐621‐6009 [email protected] The University of Texas School of Law Continuing Legal Education ▪ 512.475.6700 ▪ utcle.org Bernard E. (“Barney”) Jones Attorney at Law 3555 Timmons Lane, Suite 1020 • Houston, Texas 77027 • 713.621.3330 • fax 832.201.9219 • [email protected] Professional ! Board Certified, Estate Planning and Probate Law, Texas Board of Legal Specialization (since 1991) ! Fellow, American College of Trust and Estate Council (elected 1995) ! Adjunct Professor of Law (former), University of Houston Law Center, Houston, Texas, 1995 - 2001 (course: Estate Planning) ! Texas Bar Section on Real Estate, Probate and Trust Law " Council Member, 1998 - 2002; Grantor Trust Committee Chair, 1999 - 2002; Community Property Committee Chair, 1999 - 2002; Subcommittee on Revocable Trusts chair, 1993 - 94 " Subcommittee on Transmutation, member, 1995 - 99, and principal author of statute and constitutional amendment enabling "conversions to community" Education University of Texas, Austin, Texas; J.D., with honors, May 1983; B.A., with honors, May 1980 Selected Speeches, Publications, etc. ! Drafting Down (KISS Revisited) - The Utility and Fallacy of Simplified Estate Planning, 20th Annual State Bar of Texas Advanced Drafting: Estate Planning -

INCOTERMS® 2010: Codified Mercantile Custom Or Standard Contract Terms?

INCOTERMS® 2010: CODIFIED MERCANTILE CUSTOM OR STANDARD CONTRACT TERMS? Juana Coetzee BA LLB LLM LLD Senior Lecturer, Department of Mercantile Law, Stellenbosch University* 1 Introduction Trade terms represent commercial customs and usages1 that have developed over centuries in a particular trade or region.2 They function as contractual terms which indicate in abbreviated form the seller and buyer’s respective delivery obligations, and at the same time they allocate the risk and costs connected to delivery.3 When trade terms are understood uniformly they fulfil a harmonisation function in international trade. Because merchants know what is expected from them, trade terms provide legal certainty, which means less disputes and lower transaction costs. However, studies have found that the understanding and interpretation of trade terms tend to differ from one country to the other or from one commercial sector to the next.4 In an effort to standardise the interpretation of trade term content, the International Chamber of Commerce (“ICC”) formulated INCOTERMS®. The first edition was published in 1936 and thereafter revised in 1953, 1967, 1976, 1980, 1990, 2000 and 2010. The rules are accepted by governments, scholars, merchants and legal practitioners worldwide5 and have been endorsed by the United * Parts of this article are based on research that was conducted for my unpublished LLD dissertation INCOTERMS as a form of Standardisation in International Sales Law: The Interplay between Mercantile Custom and Substantive Sales Law with Specific -

Introduction to Law and Legal Reasoning Law Is

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND LEGAL REASONING LAW IS "MAN MADE" IT CHANGES OVER TIME TO ACCOMMODATE SOCIETY'S NEEDS LAW IS MADE BY LEGISLATURE LAW IS INTERPRETED BY COURTS TO DETERMINE 1)WHETHER IT IS "CONSTITUTIONAL" 2)WHO IS RIGHT OR WRONG THERE IS A PROCESS WHICH MUST BE FOLLOWED (CALLED "PROCEDURAL LAW") I. Thomas Jefferson: "The study of the law qualifies a man to be useful to himself, to his neighbors, and to the public." II. Ask Several Students to give their definition of "Law." A. Even after years and thousands of dollars, "LAW" still is not easy to define B. What does law Consist of ? Law consists of enforceable rule governing relationships among individuals and between individuals and their society. 1. Students Need to Understand. a. The law is a set of general ideas b. When these general ideas are applied, a judge cannot fit a case to suit a rule; he must fit (or find) a rule to suit the unique case at hand. c. The judge must also supply legitimate reasons for his decisions. C. So, How was the Law Created. The law considered in this text are "man made" law. This law can (and will) change over time in response to the changes and needs of society. D. Example. Grandma, who is 87 years old, walks into a pawn shop. She wants to sell her ring that has been in the family for 200 years. Grandma asks the dealer, "how much will you give me for this ring." The dealer, in good faith, tells Grandma he doesn't know what kind of metal is in the ring, but he will give her $150. -

A Guide to Contract Interpretation

A GUIDE TO CONTRACT INTERPRETATION July 2014 by Vincent R. Martorana © July 2014 This guide is intended for an audience of attorneys Reed Smith LLP and does not constitute legal advice – please see All rights reserved. “Scope of this Guide and Disclaimer.” TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 A. Purpose of this Guide ............................................................ 1 B. Scope of this Guide and Disclaimer ....................................... 2 C. Author Bio ......................................................................... …. 3 II. CONTRACT-INTERPRETATION FLOW CHART .............................................. 4 III. CONTRACT-INTERPRETATION PRINCIPLES AND CASE-LAW SUPPLEMENT ........ 5 A. Determine the intent of the parties with respect to the provision at issue at the time the contract was made ............ 5 B. Defining ambiguity ............................................................... 6 1. A contract or provision is ambiguous if it is reasonably susceptible to more than one interpretation ......................... 6 a. Some courts look at whether the provision is reasonably susceptible to more than one interpretation when read by an objective reader in the position of the parties ................ 8 b. Some courts factor in a reading of the provision “by one who is cognizant of the customs, practices, and terminology as generally understood by a particular trade or business” ... 10 i. Evidence of custom and practice -

The Property Tax Lien

PROPERTY TAX BULLETIN NUMBER 150 | OCTOBER 2009 The Property Tax Lien Christopher B. McLaughlin 1. What is a property tax lien? A property tax lien is the tool a tax collector uses to collect a tax obligation from a taxpayer’s property. In technical terms, a lien is “the right to have a demand satisfied out of the property of another.” 1 A property tax lien allows the tax collector to satisfy unpaid taxes by selling the taxpayer’s real property (through foreclosure) or tangible personal property (through levy and sale) or by collecting intangible property due to the taxpayer (through the attachment of bank accounts, wages, and rents). 2. When does a tax lien attach to property? A property tax lien is not enforceable against a particular piece of property until it attaches to that property. Note that a tax lien attaches to property, not to a taxpayer. Once a tax lien attach- es to a specific property, it generally remains attached to that property until the taxes that gave rise to the lien are satisfied, regardless of who owns the property at that time. Please see Ques- tion 7 for a detailed discussion of how tax liens are discharged or extinguished. A property tax lien on real property attaches on January 1 of the year the tax is levied.2 For example, the 2009 property tax liens on real property arose on January 1, 2009, even though those property taxes are levied for the fiscal year that runs from July 1, 2009 to June 30, 2010. Christopher B.