Guide to Municipal Roads Manual©

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

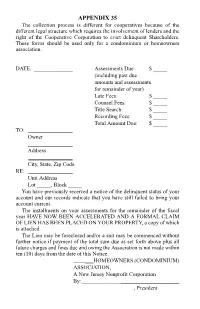

35. Notice of Acceleration of Assessment and Filing of Lien; Claim of Lien

APPENDIX 35 The collection process is different for cooperatives because of the different legal structure which requires the involvement of lenders and the right of the Cooperative Corporation to evict delinquent Shareholders. These forms should be used only for a condominium or homeowners association. DATE: ______________ Assessments Due: $ _____ (including past due amounts and assessments for remainder of year) Late Fees: $ _____ Counsel Fees: $ _____ Title Search: $ _____ Recording Fees: $ _____ Total Amount Due: $ _____ TO: ________________ Owner ________________ Address ________________ City, State, Zip Code RE: ________________ Unit Address Lot _____, Block _____ You have previously received a notice of the delinquent status of your account and our records indicate that you have still failed to bring your account current. The installments on your assessments for the remainder of the fiscal year HAVE NOW BEEN ACCELERATED AND A FORMAL CLAIM OF LIEN HAS BEEN PLACED ON YOUR PROPERTY, a copy of which is attached. The Lien may be foreclosed and/or a suit may be commenced without further notice if payment of the total sum due as set forth above plus all future charges and fines due and owing the Association is not made within ten (10) days from the date of this Notice. ___HOMEOWNERS (CONDOMINIUM) ASSOCIATION, A New Jersey Nonprofit Corporation By: _____________________ , President CLAIM OF LIEN CLAIM OF LIEN _________ Homeowners (Condominium) Association, Inc., a New Jersey nonprofit corporation (“Association”), with an address at , , New Jersey, , in care of (Management Company) , hereby claims a lien for unpaid assessments, charges and expenses in accordance with the terms of that certain Declaration of Covenants and Restrictions (“Declaration”) or Master Deed (“Master Deed”) for _______ recorded on in the County Clerk's Office in Deed Book Page et seq. -

G.S. 45-36.24 Page 1 § 45-36.24. Expiration of Lien of Security

§ 45-36.24. Expiration of lien of security instrument. (a) Maturity Date. – For purposes of this section: (1) If a secured obligation is for the payment of money: a. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on a date specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If no such date is specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation. b. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand or on a date specified in the secured obligation, whichever first occurs, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If all sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand and no alternative date is specified in the secured obligation for payment in full, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date of the secured obligation. c. The maturity date of the secured obligation is "stated" in a security instrument if (i) the maturity date of the secured obligation is specified as a date certain in the security instrument, (ii) the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation is specified in the security instrument, or (iii) the maturity date of the secured obligation or the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation can be ascertained or determined from information contained in the security instrument, such as, for example, from a payment schedule contained in the security instrument. -

Guidance Note

Guidance note The Crown Estate – Escheat All general enquiries regarding escheat should be Burges Salmon LLP represents The Crown Estate in relation addressed in the first instance to property which may be subject to escheat to the Crown by email to escheat.queries@ under common law. This note is a brief explanation of this burges-salmon.com or by complex and arcane aspect of our legal system intended post to Escheats, Burges for the guidance of persons who may be affected by or Salmon LLP, One Glass Wharf, interested in such property. It is not a complete exposition Bristol BS2 0ZX. of the law nor a substitute for legal advice. Basic principles English land law has, since feudal times, vested in the joint tenants upon a trust determine the bankrupt’s interest and been based on a system of tenure. A of land. the trustee’s obligations and liabilities freeholder is not an absolute owner but • Freehold property held subject to a trust. with effect from the date of disclaimer. a“tenant in fee simple” holding, in most The property may then become subject Properties which may be subject to escheat cases, directly from the Sovereign, as lord to escheat. within England, Wales and Northern Ireland paramount of all the land in the realm. fall to be dealt with by Burges Salmon LLP • Disclaimer by liquidator Whenever a “tenancy in fee simple”comes on behalf of The Crown Estate, except for In the case of a company which is being to an end, for whatever reason, the land in properties within the County of Cornwall wound up in England and Wales, the liquidator may, by giving the prescribed question may become subject to escheat or the County Palatine of Lancaster. -

Present Legal Estates in Fee Simple

CHAPTER 3 Present Legal Estates in Fee Simple A. THE ENGLISH LAW T THE beginning of the thirteenth century, when the royal courts of justice were acquiring effective A control of the development of private law, the possible forms of action and their limits were uncertain. It seemed then that a new form of action could be de vised to fit any need which might arise. In the course of that century the courts set themselves to limiting the possible forms of action to a definite list, defining with certainty the scope of permitted actions, and so refusing relief upon states of fact which did not fall within the fixed limits of permitted forms of action. This process, of course, operated to fix and limit the classes of private rights protected by law.101 A parallel process went on with respect to interests in land. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, when alienation of land was becoming possible, it seemed that any sort of interest which ingenuity could devise might be created by apt terms in the transfer creating the interest. Perhaps the form of the gift could create interests of any specified duration, with peculiar rules for descent, with special rights not ordinarily in cident to ownership, or deprived of some of the ordinary incidents of ownership. As in the case of the forms of action, the courts set themselves to limiting the possible interests in land to a definite list, defining with certainty 1o1 Maitland, FoRMS OF ACTION AT CoMMON LAW 51-52 (reprint 1941). 37 38 PERPETUITIES AND OTHER RESTRAINTS the incidents of permitted interests, and refusing to en force provisions of a gift which would add to or subtract from the fixed incidents of the type of interest conveyed. -

The Law of Property

THE LAW OF PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL READINGS Class 14 Professor Robert T. Farley, JD/LLM PROPERTY KEYED TO DUKEMINIER/KRIER/ALEXANDER/SCHILL SIXTH EDITION Calvin Massey Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law The Emanuel Lo,w Outlines Series /\SPEN PUBLISHERS 76 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 http://lawschool.aspenpublishers.com 29 CHAPTER 2 FREEHOLD ESTATES ChapterScope ------------------- This chapter examines the freehold estates - the various ways in which people can own land. Here are the most important points in this chapter. ■ The various freehold estates are contemporary adaptations of medieval ideas about land owner ship. Past notions, even when no longer relevant, persist but ought not do so. ■ Estates are rights to present possession of land. An estate in land is a legal construct, something apart fromthe land itself. Estates are abstract, figments of our legal imagination; land is real and tangible. An estate can, and does, travel from person to person, or change its nature or duration, while the landjust sits there, spinning calmly through space. ■ The fee simple absolute is the most important estate. The feesimple absolute is what we normally think of when we think of ownership. A fee simple absolute is capable of enduringforever though, obviously, no single owner of it will last so long. ■ Other estates endure for a lesser time than forever; they are either capable of expiring sooner or will definitely do so. ■ The life estate is a right to possession forthe life of some living person, usually (but not always) the owner of the life estate. It is sure to expire because none of us lives forever. -

Chapter 8: Transportation - 1 Unincorporated Horry County

INTRODUCTION Transportation plays a critical role in people’s daily routine and representation from each of the three counties, municipalities, addresses a minimum of a 20-year planning horizon and includes quality of life. It also plays a significant role in economic COAST RTA, SCDOT, and WRCOG. GSATS agencies analyze the both long- and short-range strategies and actions that lead to the development and public safety. Because transportation projects short- and long-range transportation needs of the region and offer development of an integrated, intermodal transportation system often involve local, state, and often federal coordination for a public forum for transportation decision making. that facilitates the efficient movement of people and goods. The funding, construction standards, and to meet regulatory Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP) is a 5 year capital projects guidelines, projects are identified many years and sometimes plan adopted by the GSATS and by SCDOT. The local TIP also decades prior to the actual construction of a new facility or includes a 3 year estimate of transit capital and maintenance improvement. Coordinating transportation projects with future requirements. The projects within the TIP are derived from the MTP. growth is a necessity. The Waccamaw Regional Council of Governments (WRCOG) not The Transportation Element provides an analysis of transportation only assists in managing GSATS, but it also helps SCDOT with systems serving Horry County including existing roads, planned or transportation planning outside of the boundaries of the MPO for proposed major road improvements and new road construction, Horry, Georgetown, and Williamsburg counties. SCDOT partnered existing transit projects, existing and proposed bicycle and with WRCOG to develop the Rural Long-Range Transportation Plan pedestrian facilities. -

Status of the Opera10r's Lien in Law and in Equity

1987) THE OPERATOR'S LIEN 87 STATUSOF THE OPERA10R'S LIEN IN LAWAND IN EQUITY KAREN L. PETIIFER • This paper examines the Operator's lien. as it is written in the 1981 Canadian Association of Petroleum Landmen Operating Procedure. and the law of Canada. the Commonwealth and the United States to determine the nature ofthe Operator's interest and the steps which the Operator must take to perfect its security and succeed in priority contests with other creditors. I. THE OPERATING AGREEMENT The Canadian Association of Petroleum Landmen ("CAPC') has developed four standard-form Operating Agreements since 1969to govern the legal relationship between Joint-Operators who have participating interests in the petroleum substances leased from either private owners or the Crown. The Agreement is designed to supplement a basic contract among the parties which may address matters such as drilling obligations. 1 It is the Operating Agreement which eventually governs day-to-day operations, including activities such as the drilling, completing, equipping and operating of joint interest wells. The most recent standard-form CAPL Agreement was drafted in 1981 and is used frequently by the industry. Article XV of the Agreement defines the relationship of the parties as tenants in common and not as creating a partnership, joint venture or association. 2 The Joint-Operators collectively agree to appoint one party as the Operator to carry out operations "for the joint account", which means " ... for the benefit, interest, ownership, risk, cost, expense and obligation of the parties hereto in proportion to each party's participating interest" .3 The Operator is granted the control and management of the operation of the joint lands. -

Engineering Section Report

all over the state. Imagine the chaotic conditions we could expect if our snowplows never did get on the road; or, if for some reason all traffic stopped, even for a single day. No mail, no food, no visiting, no living would be the result. Our Department and Its functions are indeed extremely news worthy activities. The Public Relations Section news releases are for warded to 4 daily papers in this state and to 4 metropolitan newspapers in nearby states. Copy is provided regularly for weekly newspapers, 10 radio stations, and 8 magazines. A total of 331 news releases were issued during the past year, in many cases with photographs. Many other news releases were issued to individual papers for local news. Other news releases appeared a number of times in trade magazines of national circulation. The photographic laboratory supplied the pictures to accompany the news releases. The photo graphic personnel also showed films and slides about the Department's work on dirt roads and beach protection work at the request of local civic organizations. A complete photographic record is maintained for the Department of construction work, existing conditions, right of-way problems, experimentation, and tests. II. ACTIVITIES OF THE ENGINEERING SECTION PLANNING AND DESIGN DIVISION The Planning and Design Division coordinates the activities of the Road Design Section, the Bridge Section, the Right-of-Way Section, the Planning Section, and the Utilities Section with the other sections of the Department which are concerned with any aspect of contract plan preparation. Upon completion of the plans they are assembled with proposals, special provisions, right-of-way agreements, and other factual information which are then forwarded to the Federal Aid Section. -

In Defense of the Fee Simple Katrina M

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 93 | Issue 1 Article 1 11-2017 In Defense of the Fee Simple Katrina M. Wyman New York University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation 93 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1 (2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized editor of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\93-1\NDL101.txt unknown Seq: 1 15-NOV-17 13:44 ARTICLES IN DEFENSE OF THE FEE SIMPLE Katrina M. Wyman* Prominent economically oriented legal academics are currently arguing that the fee simple, the dominant form of private landownership in the United States, is an inefficient way for society to allocate land. They maintain that the fee simple blocks transfers of land to higher value uses because it provides property owners with a perpetual monopoly. The critics propose that landown- ership be reformulated to enable private actors to forcibly purchase land from other private own- ers, similar to the way that governments can expropriate land for public uses using eminent domain. While recognizing the significance of the critique, this Article takes issue with it and defends the fee simple. The Article makes two main points in defense of the fee simple. First, addressing the critique on its own economic terms, the Article argues that the critics have not established that there is a robust economic argument for dispensing with the fee simple. -

The Property Tax Lien

PROPERTY TAX BULLETIN NUMBER 150 | OCTOBER 2009 The Property Tax Lien Christopher B. McLaughlin 1. What is a property tax lien? A property tax lien is the tool a tax collector uses to collect a tax obligation from a taxpayer’s property. In technical terms, a lien is “the right to have a demand satisfied out of the property of another.” 1 A property tax lien allows the tax collector to satisfy unpaid taxes by selling the taxpayer’s real property (through foreclosure) or tangible personal property (through levy and sale) or by collecting intangible property due to the taxpayer (through the attachment of bank accounts, wages, and rents). 2. When does a tax lien attach to property? A property tax lien is not enforceable against a particular piece of property until it attaches to that property. Note that a tax lien attaches to property, not to a taxpayer. Once a tax lien attach- es to a specific property, it generally remains attached to that property until the taxes that gave rise to the lien are satisfied, regardless of who owns the property at that time. Please see Ques- tion 7 for a detailed discussion of how tax liens are discharged or extinguished. A property tax lien on real property attaches on January 1 of the year the tax is levied.2 For example, the 2009 property tax liens on real property arose on January 1, 2009, even though those property taxes are levied for the fiscal year that runs from July 1, 2009 to June 30, 2010. Christopher B. -

ROAD LAW HANDBOOK © 2020 GIVENS PURSLEY LLP Page I 15068836 11.Doc 8

RRooaadd LLaaww HHaannddbbooookk Road Creation and Abandonment Law in Idaho Christopher H. Meyer, Esq. GIVENS PURSLEY LLP 601 West Bannock Street Boise, ID 83702 Office: 208-388-1236 Fax: 208-388-1300 [email protected] www.givenspursley.com April 14, 2021 CHAPTER INDEX I. PUBLIC ROAD CREATION ...................................................................................................................... 1 A. Overview .................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Methods of public road creation ................................................................................. 1 2. Terminology — roads, highways, and rights-of-way; abandonment and vacation ....................................................................................................................... 5 3. Private prescriptive use rights based on adverse possession ....................................... 6 4. Roads may be administered by cities, counties, or highway districts. ........................ 8 5. Confusion over the label “commissioners.” ................................................................ 9 B. Blanket legislative declaration (aka legislative fiat) (pre-1881 roads)................................... 10 C. Idaho’s public road creation statute (formal declaration and prescription) ............................ 11 1. Overview ................................................................................................................... 11 2. -

Street Directory Web-2

PW=PRIVATE AREA OF TW =TOWN WAY TOWN STREET NAME AKA STREET NAME LOCATION DESCRIPTION TW YB A STREET 2nd right off Oceanside Ave Ext. from Long Beach, (at Bath House) across from Acorn St PW YV ABATTOIR DRIVE Dirt road at the end of the cul-de-sac off Jeffery Drive which is off South Side TW YB ABBEY ROAD West off Cape Neddick Rd.( Rt. 1A,) 2nd left from jct. of Shore Rd; Dead End PW YB ABENAQUI DRIVE 2nd right off Cape Neddick Rd from Shore Rd PW YV ABIGAIL LANE 1st right off McIntire Road (off Beech Ridge Rd) TW YB ACORN STREET Beacon St from Ridge Rd 1/2 way to Long Beach on left PW CN ADAMS ROAD 2nd left off Intervale Rd from Shore Rd TW CN AGAMENTICUS AVENUE Runs East off Shore Rd opposite River Rd, makes a loop TW YB AIRPORT DRIVE 1st left off Church St Ext from Rt 1A; makes a loop TW YB AIRPORT DRIVE EXTENSION 1st right off Broadway coming from Long Beach Ave PW YB ALDER STREET Paper Road 1st right off Railroad Ave Ext. from Beach Ball Field TW YH ALDIS LANE East off York St.( Rt. 1A ) [near#534]North of Harbor Beach Rd, Dead End PW CN ALGONAC AVENUE 1st right off Shore Rd after Agamenticus Ave. crosses Agamenticus Ave and goes down toward water TW CN ALGONQUIN DRIVE Right off Groundnut Hill Rd, from Mountain Rd PW YB AMHERST AVENUE Left off Reserve St from Beacon St. (toward Lond Bch. end) PW CN ANBELWOLD CIRCUIT End of Wanaque Road to Pint Cove PW YV ANDREWS WAY Off York Street [near#66] 1st left after Hilltop, across from Organug Rd and York Street Baptist Church TW YH ANGEL AVENUE Off Woodbridge Rd; on left after York Water Dist.