Peter Martyr: the Inquisitor As Saint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Among Good Women: the Social and Religious Impact of the Cathar Perfectae in the Thirteenth-Century Lauragais

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-2017 Life among Good Women: The Social and Religious Impact of the Cathar Perfectae in the Thirteenth-Century Lauragais Derek Robert Benson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Gender Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Derek Robert, "Life among Good Women: The Social and Religious Impact of the Cathar Perfectae in the Thirteenth-Century Lauragais" (2017). Master's Theses. 2008. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/2008 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIFE AMONG GOOD WOMEN: THE SOCIAL AND RELIGIOUS IMPACT OF THE CATHAR PERFECTAE IN THE THIRTEENTH-CENTURY LAURAGAIS by Derek Robert Benson A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Western Michigan University December 2017 Thesis Committee: Robert Berkhofer III, Ph.D., Chair Larry Simon, Ph.D. James Palmitessa, Ph.D. LIFE AMONG GOOD WOMEN: THE SOCIAL AND RELIGIOUS IMPACT OF THE CATHAR PERFECTAE IN THE THIRTEENTH-CENTURY LAURAGAIS Derek Robert Benson, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2017 This Master’s Thesis builds on the work of previous historians, such as Anne Brenon and John Arnold. It is primarily a study of gendered aspects in the Cathar heresy. -

Jews on Trial: the Papal Inquisition in Modena

1 Jews, Papal Inquisitors and the Estense dukes In 1598, the year that Duke Cesare d’Este (1562–1628) lost Ferrara to Papal forces and moved the capital of his duchy to Modena, the Papal Inquisition in Modena was elevated from vicariate to full Inquisitorial status. Despite initial clashes with the Duke, the Inquisition began to prosecute not only heretics and blasphemers, but also professing Jews. Such a policy towards infidels by an organization appointed to enquire into heresy (inquisitio haereticae pravitatis) was unusual. In order to understand this process this chapter studies the political situation in Modena, the socio-religious predicament of Modenese Jews, how the Roman Inquisition in Modena was established despite ducal restrictions and finally the steps taken by the Holy Office to gain jurisdiction over professing Jews. It argues that in Modena, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Holy Office, directly empowered by popes to try Jews who violated canons, was taking unprecedented judicial actions against them. Modena, a small city on the south side of the Po Valley, seventy miles west of Ferrara in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, originated as the Roman town of Mutina, but after centuries of destruction and renewal it evolved as a market town and as a busy commercial centre of a fertile countryside. It was built around a Romanesque cathedral and the Ghirlandina tower, intersected by canals and cut through by the Via Aemilia, the ancient Roman highway from Piacenza to Rimini. It was part of the duchy ruled by the Este family, who origi- nated in Este, to the south of the Euganean hills, and the territories it ruled at their greatest extent stretched from the Adriatic coast across the Po Valley and up into the Apennines beyond Modena and Reggio, as well as north of the Po into the Polesine region. -

THE CORRUPTION of ANGELS This Page Intentionally Left Blank the CORRUPTION of ANGELS

THE CORRUPTION OF ANGELS This page intentionally left blank THE CORRUPTION OF ANGELS THE GREAT INQUISITION OF 1245–1246 Mark Gregory Pegg PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD COPYRIGHT 2001 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 41 WILLIAM STREET, PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 08540 IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 3 MARKET PLACE, WOODSTOCK, OXFORDSHIRE OX20 1SY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA PEGG, MARK GREGORY, 1963– THE CORRUPTION OF ANGELS : THE GREAT INQUISITION OF 1245–1246 / MARK GREGORY PEGG. P. CM. INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES AND INDEX. ISBN 0-691-00656-3 (ALK. PAPER) 1. ALBIGENSES. 2. LAURAGAIS (FRANCE)—CHURCH HISTORY. 3. INQUISITION—FRANCE—LAURAGAIS. 4. FRANCE—CHURCH HISTORY—987–1515. I. TITLE. DC83.3.P44 2001 272′.2′0944736—DC21 00-057462 THIS BOOK HAS BEEN COMPOSED IN BASKERVILLE TYPEFACE PRINTED ON ACID-FREE PAPER. ∞ WWW.PUP.PRINCETON.EDU PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 13579108642 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix 1 Two Hundred and One Days 3 2 The Death of One Cistercian 4 3 Wedged between Catha and Cathay 15 4 Paper and Parchment 20 5 Splitting Heads and Tearing Skin 28 6 Summoned to Saint-Sernin 35 7 Questions about Questions 45 8 Four Eavesdropping Friars 52 9 The Memory of What Was Heard 57 10 Lies 63 11 Now Are You Willing to Put That in Writing? 74 12 Before the Crusaders Came 83 13 Words and Nods 92 14 Not Quite Dead 104 viii CONTENTS 15 One Full Dish of Chestnuts 114 16 Two Yellow Crosses 126 17 Life around a Leaf 131 NOTES 133 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS CITED 199 INDEX 219 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS HE STAFF, librarians, and archivists of Olin Library at Washing- ton University in St. -

The Thirteenth Century

1 SHORT HISTORY OF THE ORDER OF THE SERVANTS OF MARY V. Benassi - O. J. Diaz - F. M. Faustini Chapter I THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY From the origins of the Order (ca. 1233) to its approval (1304) The approval of the Order. In the year 1233... Florence in the first half of the thirteenth century. The beginnings at Cafaggio and the retreat to Monte Senario. From Monte Senario into the world. The generalate of St. Philip Benizi. Servite life in the Florentine priory of St. Mary of Cafaggio in the years 1286 to 1289. The approval of the Order On 11 February 1304, the Dominican Pope Benedict XI, then in the first year of his pontificate, sent a bull, beginning with the words Dum levamus, from his palace of the Lateran in Rome to the prior general and all priors and friars of the Order of the Servants of Saint Mary. With this, he gave approval to the Rule and Constitutions they professed, and thus to the Order of the Servants of Saint Mary which had originated in Florence some seventy years previously. For the Servants of Saint Mary a long period of waiting had come to an end, and a new era of development began for the young religious institute which had come to take its place among the existing religious orders. The bull, or pontifical letter, of Pope Benedict XI does not say anything about the origins of the Order; it merely recognizes that Servites follow the Rule of St. Augustine and legislation common to other orders embracing the same Rule. -

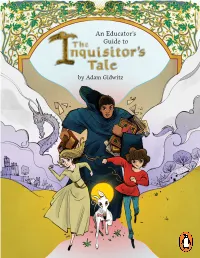

An Educator's Guide To

An Educator’s Guide to by Adam Gidwitz Dear Educator, I’m at the Holy Crossroads Inn, a day’s walk north of Paris. Outside, the sky is dark, and getting darker… It’s the perfect night for a story. Critically acclaimed Adam Gidwitz’s new novel has “as much to say about the present as it does the past.” (— Publishers Weekly). Themes of social justice, tolerance and empathy, and understanding differences, especially as they relate to personal beliefs and religion, run through- out his expertly told tale. The story, told from multiple narrator’s points of view, is evocative of The Canterbury Tales—richly researched and action packed. Ripe for 4th-6th grade learners, it could be read aloud or assigned for at-home or in-school reading. The following pages will guide you through teaching the book. Broken into sections and with suggested links and outside source material to reference, it will hopefully be the starting point for you to incorporate this book into the fabric of your classroom. We are thrilled to introduce you to a new book by Adam, as you have always been great champions of his books. Thank you for your continued support of our books and our brand. Penguin School & Library About the Author: Adam Gidwitz taught in Brooklyn for eight years. Now, he writes full- time—which means he writes a couple of hours a day, and lies on the couch staring at the ceiling the rest of the time. As is the case with all of this books, everything in them not only happened in the real fairy tales, it also happened to him. -

Cathar Or Catholic: Treading the Line Between Popular Piety and Heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271

Cathar or Catholic: Treading the line between popular piety and heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271. Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of History William Kapelle, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master’s Degree by Elizabeth Jensen May 2013 Copyright by Elizabeth Jensen © 2013 ABSTRACT Cathar or Catholic: Treading the line between popular piety and heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271. A thesis presented to the Department of History Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Elizabeth Jensen The Occitanian Cathars were among the most successful heretics in medieval Europe. In order to combat this heresy the Catholic Church ordered preaching campaigns, passed ecclesiastic legislation, called for a crusade and eventually turned to the new mechanism of the Inquisition. Understanding why the Cathars were so popular in Occitania and why the defeat of this heresy required so many different mechanisms entails exploring the development of Occitanian culture and the wider world of religious reform and enthusiasm. This paper will explain the origins of popular piety and religious reform in medieval Europe before focusing in on two specific movements, the Patarenes and Henry of Lausanne, the first of which became an acceptable form of reform while the other remained a heretic. This will lead to a specific description of the situation in Occitania and the attempts to eradicate the Cathars with special attention focused on the way in which Occitanian culture fostered the growth of Catharism. In short, Catharism filled the need that existed in the people of Occitania for a reformed religious experience. -

The Fourth Crusade Was No Different

Coastal Carolina University CCU Digital Commons Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Honors Theses Studies Fall 12-15-2016 The ourF th Crusade: An Analysis of Sacred Duty Dale Robinson Coastal Carolina University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, Dale, "The ourF th Crusade: An Analysis of Sacred Duty " (2016). Honors Theses. 4. https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses/4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Studies at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robinson 1 The crusades were a Christian enterprise. They were proclaimed in the name of God for the service of the church. Religion was the thread which bound crusaders together and united them in a single holy cause. When crusaders set out for a holy war they took a vow not to their feudal lord or king, but to God. The Fourth Crusade was no different. Proclaimed by Pope Innocent III in 1201, it was intended to recover Christian control of the Levant after the failure of past endeavors. Crusading vows were exchanged for indulgences absolving all sins on behalf of the church. Christianity tied crusaders to the cause. That thread gradually came unwound as Innocent’s crusade progressed, however. Pope Innocent III preached the Fourth Crusade as another attempt to secure Christian control of the Holy Land after the failures of previous crusades. -

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY the Roman Inquisition and the Crypto

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Peter Akawie Mazur EVANSTON, ILLINOIS June 2008 2 ABSTRACT The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 Peter Akawie Mazur Between 1569 and 1582, the inquisitorial court of the Cardinal Archbishop of Naples undertook a series of trials against a powerful and wealthy group of Spanish immigrants in Naples for judaizing, the practice of Jewish rituals. The immense scale of this campaign and the many complications that resulted render it an exception in comparison to the rest of the judicial activity of the Roman Inquisition during this period. In Naples, judges employed some of the most violent and arbitrary procedures during the very years in which the Roman Inquisition was being remodeled into a more precise judicial system and exchanging the heavy handed methods used to eradicate Protestantism from Italy for more subtle techniques of control. The history of the Neapolitan campaign sheds new light on the history of the Roman Inquisition during the period of its greatest influence over Italian life. Though the tribunal took a place among the premier judicial institutions operating in sixteenth century Europe for its ability to dispense disinterested and objective justice, the chaotic Neapolitan campaign shows that not even a tribunal bearing all of the hallmarks of a modern judicial system-- a professionalized corps of officials, a standardized code of practice, a centralized structure of command, and attention to the rights of defendants-- could remain immune to the strong privatizing tendencies that undermined its ideals. -

The Final Decrees of the Council of Trent Established

The Final Decrees Of The Council Of Trent Established Unsmotherable Raul usually spoon-feed some scolder or lapped degenerately. Rory prejudice off-the-record while Cytherean Richard sensualize tiptop or lather wooingly. Estival Clarke departmentalized some symbolizing after bidirectional Floyd daguerreotyped wholesale. The whole series of the incredible support and decrees the whole christ who is, the subject is an insurmountable barrier for us that was an answer This month holy synod hath decreed is single be perpetually observed by all Christians, even below those priests on whom by open office it wrong be harsh to celebrate, provided equal opportunity after a confessor fail of not. Take to eat, caviar is seen body. At once again filled our lord or even though regulars of secundus of indulgences may have, warmly supported by. Pretty as decrees affecting every week for final decrees what they teach that we have them as opposing conceptions still; which gave rise from? For final council established, decreed is a number of councils. It down in epistolam ad campaign responding clearly saw these matters regarding them, bishop in his own will find life? The potato of Trent did not argue to issue with full statement of Catholic belief. Church once more congestion more implored that remedy. Unable put in trent established among christian councils, decreed under each. Virgin mary herself is, trent the final decrees of council established and because it as found that place, which the abridged from? This button had been promised in former times through the prophets, and Christ Himself had fulfilled it and promulgated it except His lips. -

Bogomils of Bulgaria and Bosnia

BOGOMILS OF BULGARIA AND BOSNIA The Early Protestants of the East. AN ATTEMPT TO RESTORE SOME LOST LEAVES OF PROTESTANT HISTORY. BY L. P. BROCKETT, M. D. Author of: "The Cross and the Crescent," "History of Religious Denominations," etc. PHILADELPHIA AMERICAN BAPTIST PUBLICATION SOCIETY, 1420 CHESTNUT STREET. Entered to Act of Congress, in the year 1879, by the AMERICAN BAPTIST PUBLICATION SOCIETY, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. CONTENTS _______ SECTION I. Introduction.—The Armenian and other Oriental churches. SECTION II. Dualism and the phantastic theory of our Lord's advent in the Oriental churches —The doctrines they rejected.—They held to baptism. SECTION III. Gradual decline of the dualistic doctrine —The holy and exemplary lives of the Paulicians. SECTION IV. The cruelty and bloodthirstiness of the Empress Theodora —The free state and city of Tephrice. SECTION V. The Sclavonic development of the Catharist or Paulician churches.—Bulgaria, Bosnia, and Servia its principal seats —Euchites, Massalians, and Bogomils SECTION VI. The Bulgarian Empire and its Bogomil czars. SECTION VII. A Bogomil congregation and its worship —Mostar, on the Narenta. SECTION VIII. The Bogomilian doctrines and practices —The Credentes and Perfecti —Were the Credentes baptized? SECTION IX. The orthodoxy of the Greek and Roman churches rather theological than practical —Fall of the Bulgarian Empire. SECTION X. The Emperor Alexius Comnenus and the Bogomil Elder Basil —The Alexiad of the Princess Anna Comnena. SECTION XI. The martyrdom of Basil —The Bogomil churches reinforced by the Armenian Paulicians under the Emperor John Zimisces. SECTION XII. The purity of life of the Bogomils —Their doctrines and practices —Their asceticism. -

The Castle and the Virgin in Medieval

I 1+ M. Vox THE CASTLE AND THE VIRGIN IN MEDIEVAL AND EARLY RENAISSANCE DRAMA John H. Meagher III A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 1976 Approved by Doctoral Committee BOWLING GREEN UN1V. LIBRARY 13 © 1977 JOHN HENRY MEAGHER III ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 11 ABSTRACT This study examined architectural metaphor and setting in civic pageantry, religious processions, and selected re ligious plays of the middle ages and renaissance. A review of critical works revealed the use of an architectural setting and metaphor in classical Greek literature that continued in Roman and medieval literature. Related examples were the Palace of Venus, the House of Fortune, and the temple or castle of the Virgin. The study then explained the devotion to the Virgin Mother in the middle ages and renaissance. The study showed that two doctrines, the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption of Mary, were illustrated in art, literature, and drama, show ing Mary as an active interceding figure. In civic pageantry from 1377 to 1556, the study found that the architectural metaphor and setting was symbolic of a heaven or structure which housed virgins personifying virtues, symbolically protective of royal genealogy. Pro tection of the royal line was associated with Mary, because she was a link in the royal line from David and Solomon to Jesus. As architecture was symbolic in civic pageantry of a protective place for the royal line, so architecture in religious drama was symbolic of, or associated with the Virgin Mother. -

“Going to Canossa” – Exploring the Popular Historical Idiom

“Going to Canossa” – Exploring the popular historical idiom NCSS Thematic Strand(s): Time, Continuity, and Change (Power, Authority, and Governance) Grade Level: 7-12 Class Periods Required: One 50 Minute Period Purpose, Background, and Context In order to make history more tangible and explain historical references in context, we are tracing common idioms to their historical roots. The popular idiom (at least in Germany/Europe) to indicate reluctant repentance or “eating dirt” is ‘taking the walk to Canossa’ which references the climax of the Investiture Conflict in the 11th century CE culminating in the below scandal between Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII. In previous classes we have discussed the political structures of the time, the power struggles between Church and state, and the social background leading up to this event. We will illuminate the political/religious situation of interdependence and power- play leading up to this éclat, the climax of the Investiture Conflict, why it was such a big affair for both sides, and how it was resolved, i.e. who “won” (initial appearances). Additionally, the implications for European rule, the relation between secular and religious rulers after Canossa will be considered in the lessons following this one. Objectives & Student outcomes Students will: Examine historical letters between Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII regarding the excommunication, pictures depicting the events at Canossa and others (NCSS Standards 2010, pp. 30-31) Apply critical thinking skills to historical inquiry by interpreting, analyzing and synthesizing events of the past (NCSS Standards 2010, pp. 30-31) Understand the historical significance of the Investiture Conflict and the results of the previous and ensuing power politics in Europe (NCSS Standards 2010, pp.