Tracing the Impact of Bangalore's Urbanisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consultancy Services for Preparation of Detailed Feasibility Report For

Page 691 of 1031 Consultancy Services for Preparation of Detailed Feasibility Report for the Construction of Proposed Elevated Corridors within Bengaluru Metropolitan Region, Bengaluru Detailed Feasibility Report VOL-IV Environmental Impact Assessment Report Table 4-7: Ambient Air Quality at ITI Campus Junction along NH4 .............................................................. 4-47 Table 4-8: Ambient Air Quality at Indian Express ........................................................................................ 4-48 Table 4-9: Ambient Air Quality at Lifestyle Junction, Richmond Road ......................................................... 4-49 Table 4-10: Ambient Air Quality at Domlur SAARC Park ................................................................. 4-50 Table 4-11: Ambient Air Quality at Marathhalli Junction .................................................................. 4-51 Table 4-12: Ambient Air Quality at St. John’s Medical College & Hospital ..................................... 4-52 Table 4-13: Ambient Air Quality at Minerva Circle ............................................................................ 4-53 Table 4-14: Ambient Air Quality at Deepanjali Nagar, Mysore Road ............................................... 4-54 Table 4-15: Ambient Air Quality at different AAQ stations for November 2018 ............................. 4-54 Table 4-16: Ambient Air Quality at different AAQ stations - December 2018 ................................. 4-60 Table 4-17: Ambient Air Quality at different AAQ stations -

140205 Visionplan Bangalore Lakes.Indd

February 10, 2014 Shri. T. Sham Bhatt Commissioner Bangalore Development Authority T. Chowdaiah Road, Kumara Park West Bangalore 560 020 Dear Commissioner, Per the Memorandum of Agreement dated November 6th, 2012, between the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) and Invicus Engineering in collaboration with the Sherwood Institute and Carollo Engineering, please find attached the Vision Plan for the restoration of the lakes of Bangalore and a framework for their regeneration. The intent of this Vision Plan is to increase the understanding of what steps need to be taken to allow the City of Bangalore to regenerate its lakes, the importance of their role in a City-wide sustainable water supply system, and to start a conversation about how such steps can and should be financed. We would like to thank you for signing the MOA and acknowledge the contribution of Mr. Chickarayappa, Mr. Nayak and Mr. Manjappa of the BDA and Mr. Akash with Sky Group for providing the GIS data used in our preparation of this Vision Plan. We look forward to reviewing this plan with the BDA and receiving the BDA’s feedback. Best Regards, John Leys Associate Director Sherwood Institute Better Lakes, Better Bangalore BETTER LAKES, BETTER BANGALORE: VISION PLAN 1 Introduction Purpose of the Vision Plan Stakeholder Outreach Process The Challenege Background Land Use Water Resources & Infrastructure Case Study: Sankey Tank, Bangalore Bellandur Lake Vision 2035 Bangalore’s Potential as a Global City Global City-Making Principles Case Study: Plan Verde, Mexico City Open -

Suncity Euphoria

https://www.propertywala.com/suncity-euphoria-bangalore Suncity Euphoria - Iblur Village, Bangalore living on the water edge Sun City Euphoria Project is spread across 4 acres of land consisting of ground+ three upper floors having its own club house & swimming pool which will be ready by June 2008. Project ID : J310488119 Builder: Corporate lesire Properties: Apartments / Flats Location: Suncity Euphoria,Outer Ring Road, Iblur Village, Bangalore (Karnataka) Completion Date: Aug, 2011 Status: Started Description Sun City Euphoria Project is spread across 4 acres of land consisting of ground+ three upper floors having its own club house & swimming pool which will be ready by June 2008. Once in a life time an opportunity arrives where one can live on the banks of a serene lake. Living on the water's edge. Imagine living on the water's edge amidst the cool surroundings of one of Bangalore city's largest lake. Yes, finally your "dream come true apartment" is here located conveniently at Bellandur Lake,Iblur Village in close proximity to Koramangala and the upcoming hi-tech city on the IT Corridor. The entire project comprises of 3 apartment blocks with a total of 164 apartments are elegantly designed, spacious and well ventilated.The Project is an annex to Sun City which is one of the Mega condominiums. Amenities::- Garden Swimming Pool Play Area 24Hr Backup Maintenance Staff Security Intercom Club House Gymnasium Proximity Landmarks :- Prominent landmark nearby: Close to all IT companies, very strategically located School nearby (within 5 kms): Mayflower, Shem-rock Tinker Bells, Apple Kids, DRS Kids, Podar Happy Kids, India International, St. -

Download Newsletter

Volume 3, Issue 8, November, 2019 BENGALURU APARTMENTS MAKING BENGALURU OPERATIONALLY OUTSTANDING & SUSTAINABLE BANGALOREBANGALORE APARTMENTS’APARTMENTS’ FEDERAFEDERATIONTION NNEEWWSSLLEETTTTEERR Dear Apartment Resident, The second edition of our event BAMBOOS-2019 concluded successfully on 24th November 2019! The event saw 20 clusters represent on various themes, over 30 sponsor stalls showcasing various sustainable & utility solutions for apartment residents. Over 3500 apartment residents and interested citizens visited the event, and many also interacted with the press and media who visited the stalls. There was a spectacular fire safety show, and talks by dignitaries of various civic departments, and some important announcements for apartment community. BAMBOOS’19 was surely bigger and better than before, and projected the unity, strength & contributions of apartment communities towards making Bengaluru sustainable. The various apartment management processes under seven broad themes - Water, Solid Waste Management (SWM), Energy, Apartment Management Software, Safety, Community Welfare & Conveniences, and Civic Engagement, saw clusters presenting on stage as well. The presentations, pictures, the enthusiasm and exhuberance on all aspects of BAMBOOS has been captured & is available on www.baf.org.in. This knowledge sharing will benefit not just BAF members but also the entire apartment community. BAF governing council is proud to take this lead in enabling & empowering the apartment community to be proud contributors to the society. CONGRATULATIONS BAMBOOS 2019 saw the launch of 2 great initiatives by BAF AVEnUES and MADHURA The launch version of AVEnUES booklet has 18 different topics on apartment processes. We do hope all of you have taken your copies for the association during BAMBOOS’19. MADHURA – a group health insurance scheme targeted for domestic staff working in apartments was also launched at BAMBOOS. -

Environmental Impact Assessment (Draft) Vol

Environmental Impact Assessment (Draft) Vol. 3 of 6 June 2020 India: Bengaluru Metro Rail Project Phase 2B (Airport Metro Line) KR Puram to Kempegowda International Airport Prepared by Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation Ltd. (BMRCL), India for the Asian Development Bank. NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of India and its agencies ends on 31 March. “FY” before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2019 ends on 31 March 2019. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to United States dollars. This environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Environmental Impact Assessment - KR Puram to KIA Section of BMRCL Figure 4- 20: Vibration Monitoring Locations 150. The predominant frequencies and amplitude of the vibration depend on many factors including suspension system of operating vehicles, soil type and stratification, traffic time peak/non-peak hours, distance from the road and type of building and the effects of these factors are interdependent. Threshold limit (upper limit) has been set to 0.5 mm/s. -

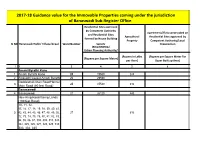

2017-18 Guidance Value for the Immovable Properties Coming Under the Jurisdiction of Banaswadi Sub-Register Office

2017-18 Guidance value for the Immovable Properties coming under the jurisdiction of Banaswadi Sub-Register Office. Residential Sites approved by Competent Authority Apartments/Flats constructed on and Residential Sites Agricultural Residential Sites approved by formed by House Building Property Competent Authority/Local Sl NO Banaswadi Hobli/ Village/Area/ Ward Number Society Organization (BDA/BMRDA/ Urban Planning Authority/ (Rupees in Lakhs (Rupees per Square Meter For (Rupees per Square Meter) per Acre) Super Built up Area) 1 2 3 4 5 6 Amani Byrathi Kane 1 Amani Byrathi Kane 25 19580 245 2 Arkavathi Layout Amani Byrathi 25 29590 Geddalahalli Main Road/Hennur 3 25 45540 610 Main Road (80 feet Road) Banasawadi 4 Banasawadi 27 26100 490 New Ring Road facing Lands (100 feet Road) 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 38, 39, 40, 41, 5 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 27 610 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 308, 309, 310, 323, 324, 325, 326, 327, 328, 329, 332, 333, 334, 335 Banasawadi - 6 Ramamurthy NagaraMain Road 27 46000 (80 feet Road) 7 Ex-Servicemen Colony 27 32560 8 Chandramma Layout 27 32540 9 Kalyanamma Layout 27 32560 10 Lakshmamma Layout 27 32560 11 Green Park Layout 27 32560 12 Vijaya Bank Colony 27 32560 13 Annaiah Reddy Layout 27 32560 14 Skyline Apartments (Apartments) 27 75900 Canapoy Apartments 15 27 37070 (Apartments) 16 Ex- Servicemen Colony/Layout 27 32600 17 Gopala Reddy Layout 27 32600 18 Krishna Reddy Layout 27 32560 19 100 feet Road/10 th Main Road 27 65120 Sai Charita Green Oaks 20 27 55000 (Apartments) -

Bangalore for the Visitor

Bangalore For the Visitor PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 12 Dec 2011 08:58:04 UTC Contents Articles The City 11 BBaannggaalloorree 11 HHiissttoorryoofBB aann ggaalloorree 1188 KKaarrnnaattaakkaa 2233 KKaarrnnaattaakkaGGoovv eerrnnmmeenntt 4466 Geography 5151 LLaakkeesiinBB aanngg aalloorree 5511 HHeebbbbaalllaakkee 6611 SSaannkkeeyttaannkk 6644 MMaaddiiwwaallaLLaakkee 6677 Key Landmarks 6868 BBaannggaalloorreCCaann ttoonnmmeenntt 6688 BBaannggaalloorreFFoorrtt 7700 CCuubbbboonPPaarrkk 7711 LLaalBBaagghh 7777 Transportation 8282 BBaannggaalloorreMM eettrrooppoolliittaanTT rraannssppoorrtCC oorrppoorraattiioonn 8822 BBeennggaalluurruIInn tteerrnnaattiioonnaalAA iirrppoorrtt 8866 Culture 9595 Economy 9696 Notable people 9797 LLiisstoof ppee oopplleffrroo mBBaa nnggaalloorree 9977 Bangalore Brands 101 KKiinnggffiisshheerAAiirrll iinneess 110011 References AArrttiicclleSSoo uurrcceesaann dCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111155 IImmaaggeSS oouurrcceess,LL iicceennsseesaa nndCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111188 Article Licenses LLiicceennssee 112211 11 The City Bangalore Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Bangalore — — metropolitan city — — Clockwise from top: UB City, Infosys, Glass house at Lal Bagh, Vidhana Soudha, Shiva statue, Bagmane Tech Park Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Location of Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) in Karnataka and India Coordinates 12°58′′00″″N 77°34′′00″″EE Country India Region Bayaluseeme Bangalore 22 State Karnataka District(s) Bangalore Urban [1][1] Mayor Sharadamma [2][2] Commissioner Shankarlinge Gowda [3][3] Population 8425970 (3rd) (2011) •• Density •• 11371 /km22 (29451 /sq mi) [4][4] •• Metro •• 8499399 (5th) (2011) Time zone IST (UTC+05:30) [5][5] Area 741.0 square kilometres (286.1 sq mi) •• Elevation •• 920 metres (3020 ft) [6][6] Website Bengaluru ? Bangalore English pronunciation: / / ˈˈbæŋɡəɡəllɔəɔər, bæŋɡəˈllɔəɔər/, also called Bengaluru (Kannada: ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು,, Bengaḷūru [[ˈˈbeŋɡəɭ uuːːru]ru] (( listen)) is the capital of the Indian state of Karnataka. -

Bangaluru.Qxp:Layout 1

BENGALURU WATER SOURCES THE WATER-WASTE PORTRAIT Hesaraghatta reservoir Despite its highrises and malls, the ‘Silicon Valley’ 18 km and ‘Garden City’ of India fares badly as far as Arkavathi river infrastructure is concerned, and has lost its famous lakes to indiscriminate disposal of waste and encroachment Chamaraja Sagar BENGALURU reservoir TG HALLI 35 km WTP Boundary under Bangalore Development Authority V-Valley Boundary under Comprehensive Development Plan TK HALLI Sewage treatment plant (STP) WTP Shiva anicut STP (proposed) Cauvery river 90 km (Phase I - Stage 1-4) (future source: Phase II by 2011-14) Water treatment plant (WTP) Hesaraghatta Sewage pumping stations tank Ganayakanahalli Kere Baalur Kere Waterways Disposal of sewage Yelahanka tank Dakshina Pinakini river Waterbodies YELAHANKA Jakkur tank Doddagubbi Kumudvathi river tank Rampur HEBBAL tank Arkavathi river JAKKUR NAGASANDRA Yelamallappachetty Mattikere Hennur Kere tank SPS RAJA CANAL K R PURAM Sadarmangal Ulsoor tank Chamaraja Sagar tank reservoir Byrasandra tank CUBBON PARK V Valley Vrishabhavathi river KADABEESANAHALLI SPS Vartur tank MYLASANDRA KEMPAMBUDHI LALBAGH Hosakerehalli Bellandur tank K & C VALLEY tank V-VALLEY Arkavathi river MADIVALA Bomanahalli tank Nagarbhavi river Begur Hulimavu tank tank Muttanallur Kere Source: Anon 2011, 71-City Water-Excreta Survey, 2005-06, Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi 304 KARNATAKA THE CITY Municipal area 561 sq km Total area 740 sq km Bengaluru Population (2005) 6.5 million Population (2011), as projected in 2005-06 7.5 million THE WATER Demand angalored’, a slang for being rendered jobless, is a term Total water demand as per city agency (BWSSB) 1125 MLD (2010) made famous by the city’s outsourcing business; Per capita water demand as per BWSSB 173 LPCD ironically, this very business has brought jobs and Total water demand as per CPHEEO @ 175 LPCD 1138 MLD ‘B Sources and supply growth to the capital city of Karnataka. -

OBW Digital Brochure.Pdf

SHOT AT LOCATION ONE HOME. INFINITE POSSIBILITIES. Discover Bangalore's most-awarded living precinct, replete with incredible amenities and facilities, a growing multi-cultural community, designer landscapes and a great, central location. ONE CENTRAL LOCATION.BOUNDLESS CONNECTIVITY. KEMPEGOWDA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT RAJARAJESHWARI NAGAR 0.10 km - Orion Mall SAHAKAR NAGAR Aster CMI Hospital 0.10 km - Sheraton Hotel Tum kur Road 0.10 km - World Trade Center Hebbal Lake Esteem Mall Out er Ring Manyata 0.20 km - Metro Station Road Tech Park J.P. Park Movenpick HEBBAL Hebbal Junction 0.20 km - Brigade School Vivanta by Taj 0.20 km - Columbia Asia Hospital DOLLARS COLONY Indicative Metro Line Peenya Industrial Area PVR Vaishnavi Four Seasons 0.35 km - Metro Cash and Carry Sapphire Mall IISC Campus MAHALAKSHMI LAYOUT IISC Underpass 3.50 km - Sadashivanagar Mekhri Circle Metro Station C.V. Raman Road 8.00 km - MG Road R.M.V. EXTENSION Palace Grounds oad R Sankey Tank 34.0 km - KIAL Columbia Asia Hospital er Ring Palace Orchards 5.00 km - Peenya t Ou SADASHIVANAGAR oad Sheraton MALLESWARAM R oad R BENSON TOWN Temple Orion Mall d d umar KUMARA PARK Bangalore r k FRAZER TOWN Cho . Raj NANDINI LAYOUT r Bangalore Golf Club ITC Windsor D RAJAJINAGAR Manor Cantonment Railway Station Spandana Hospital Mantri Mall Cunningham Road oad R Le Meridien Indic a Millers Ulsoor Lake tive Met Suvarna r o Line Vidhana Soudha National Academy For Learning (NAFL) M.G. Road Lavelle Road J W Marriott UB City Cubbon Park The Ritz-Carlton To view our location on Google Maps, N W E please click here S MAP NOT TO SCALE ONE ABODE. -

Wetlands: Treasure of Bangalore

WETLANDS: TREASURE OF BANGALORE [ABUSED, POLLUTED, ENCROACHED & VANISHING] Ramachandra T.V. Asulabha K. S. Sincy V. Sudarshan P Bhat Bharath H. Aithal POLLUTED: 90% ENCROACHED: 98% Extent as per BBMP-11.7 acres VIJNANAPURA LAKE Encroachment- 5.00acres (polygon with red represents encroachments) ENVIS Technical Report: 101 January 2016 Energy & Wetlands Research Group, CES TE 15 Environmental Information System [ENVIS] Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore - 560012, INDIA Web: http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/energy/, http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/biodiversity Email: [email protected], [email protected] ETR 101, Energy & Wetlands Research Group, CES, IISc WETLANDS: TREASURE OF BANGALORE [ABUSED, POLLUTED, ENCROACHED & VANISHING] Ramachandra T.V. Asulabha K. S. Sincy V. Sudarshan P Bhat Bharath H. Aithal © Energy & Wetlands Research Group, CES TE15 Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Bangalore 560012, India Citation: Ramachandra T V, Asulabha K S, Sincy V, Sudarshan Bhat and Bharath H.Aithal, 2015. Wetlands: Treasure of Bangalore, ENVIS Technical Report 101, Energy & Wetlands Research Group, CES, IISc, Bangalore, India ENVIS Technical Report 101 January 2016 Energy & Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences, TE 15 New Bioscience Building, Third Floor, E Wing Indian Institute of Science Bangalore 560012, India http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/energy, http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/biodiversity Email: [email protected], [email protected] Note: The views expressed in the publication [ETR 101] are of the authors and not necessarily reflect the views of either the publisher, funding agencies or of the employer (Copyright Act, 1957; Copyright Rules, 1958, The Government of India). -

The Role of Policies of Lake Water Management in Bangalore, India Lavanya Vikram 1, Neelima Reddy 2 1,2 MSRIT, Bangalore, Karnataka

The role of Policies of Lake Water Management in Bangalore, India Lavanya Vikram 1, Neelima Reddy 2 1,2 MSRIT, Bangalore, Karnataka Abstract: Water pollution is a serious problem in India as its surface water resource and a growing percentage of its groundwater reserves are contaminated by pollutants. The high incidence of severe contamination near urban areas indicates that the industrial and domestic sectors contributing to water pollution is much higher. Water as an environmental resource is regenerative in the sense, that it could absorb pollution loads up to certain levels without affecting its quality. In fact there could be a problem of water pollution only if the pollution loads exceed the natural regenerative capacity of a water resource. The control of water pollution is therefore to reduce the pollution loads from anthropogenic activities to the natural regenerative capacity of the resource. The benefits of preservation of water quality are manifold. Agricultural run-offs affect groundwater and surface water sources as they contain pesticide and fertilizer residues. Fertilizers have an indirect adverse impact on water resources. Indeed, by increasing the nutritional content of water courses, fertilizers allow organisms to proliferate. Storm water runoff from urban areas is a major source for contamination of water. It should be clearly understood that the role of policies to be compensated fully for the damages from any kind of pollution. Using available data and case studies, this paper aims to provide an overview of the extent, impacts, and control of water pollution in India, taking the case of lakes in Bangalore. Keywords: water pollution, environmental issues, lakes, land use, guidelines 1. -

Comparative Water Quality Assessment of a Tropical and A

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2018; 7(4): 2246-2249 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 JPP 2018; 7(4): 2246-2249 Comparative water quality assessment of a Received: 05-05-2018 Accepted: 10-06-2018 tropical and a temperate lake of India Asmat Rashid Division of Environmental Asmat Rashid, Mohammad Aneesul Mehmood, Humaira Qadri, Rouf Science, Sher-e- Kashmir Ahmad Bhat and Gowhar Hamid Dar University of Agricultural Science and Technology, Shalimar campus, Srinagar, Abstract Jammu and Kashmir, India Two urban lakes were selected for this investigation, Dal lake Srinagar Kashmir and Bellunder lake Bangalore. The two lakes are having a greater importance in their respective cities or we can say that Mohammad Aneesul Mehmood they are the main water bodies in these cities providing water for irrigation, recreation, sports events, Department of Environmental domestic use, commercial use, and tourism also. The study is based on physico chemical parameters of Science, Sri Pratap College both lakes and then comparison of both lakes and intend outcome. The Dal lake is a Himalayan urban campus, Cluster University lake which is mostly used for tourism, it is India’s most beautiful and second largest lake in state of Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, Jammu and Kashmir. Secondly the Bellunder lake providing water for irrigation, recreation, sports India events, domestic use, commercial use, also situated on the extreme eastern part of Bangalore city located in Deccan plateau of south Indian peninsula, the terrain of region is relatively flat and sloping towards Humaira Qadri Department of Environmental south of Bangalore city. Three water samples were collected at three locations from the three basins of Science, Sri Pratap College the Dal Lake and Bellunder Lake respectively.