The Scripting of a National History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rule of Law and Urban Development

The Rule of Law and Urban Development The transformation of Singapore from a struggling, poor country into one of the most affluent nations in the world—within a single generation—has often been touted as an “economic miracle”. The vision and pragmatism shown by its leaders has been key, as has its STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS notable political stability. What has been less celebrated, however, while being no less critical to Singapore’s urban development, is the country’s application of the rule of law. The rule of law has been fundamental to Singapore’s success. The Rule of Law and Urban Development gives an overview of the role played by the rule of law in Singapore’s urban development over the past 54 years since independence. It covers the key principles that characterise Singapore’s application of the rule of law, and reveals deep insights from several of the country’s eminent urban pioneers, leaders and experts. It also looks at what ongoing and future The Rule of Law and Urban Development The Rule of Law developments may mean for the rule of law in Singapore. The Rule of Law “ Singapore is a nation which is based wholly on the Rule of Law. It is clear and practical laws and the effective observance and enforcement and Urban Development of these laws which provide the foundation for our economic and social development. It is the certainty which an environment based on the Rule of Law generates which gives our people, as well as many MNCs and other foreign investors, the confidence to invest in our physical, industrial as well as social infrastructure. -

Interview NTD Full Transcript.Pdf

INTERVIEW Mr Ngiam Tong Dow Singapore – International Medical Centre: A Missed Opportunity, or Not Too Late? By Dr Toh Han Chong, Editor The Singapore healthcare sector has been in flux and yet also in transformation. While well regarded internationally to be robust and reputable, it will continue to face imminent challenges. The speaker for this year’s SMA Lecture, Mr Ngiam Tong Dow, taps on his deep and wide experience in various ministries to offer insights and wisdom on many issues: Singapore as an international medical centre, the possibility of supplier-induced demand in healthcare, as well as his political vision and opinion on Hainanese chicken rice. This is the full version of the SMA News interview with Mr Ngiam. The contents of this interview are not to be printed in whole or in part without prior approval of the Editor (email [email protected]). (For the version published in our September 2013 issue, please see http://goo.gl/DDAcyd.) SMA Lecture 2013 Dr Toh Han Chong – THC: The upcoming SMA Lecture is titled Developing Singapore as an International Medical Centre. Why did you choose this topic? Mr Ngiam Tong Dow – NTD: In Economics, there are two types of economies – production-based and knowledge-based. The former depends on land, labour and capital, but it is the latter that Singapore really needed. This was clear to me as Chairman of Economic Development Board (EDB) in the 1980s. We could not offer cheap labour and cheap land for long. We needed to have a significant niche. At that time, we identified two key areas. -

Douglas Hyde (1911-1996), Campaigner and Journalist

The University of Manchester Research Douglas Hyde (1911-1996), campaigner and journalist Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K., Gildart, K. (Ed.), & Howell, D. (Ed.) (2010). Douglas Hyde (1911-1996), campaigner and journalist. In Dictionary of Labour Biography vol. XIII (pp. 162-175). Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Published in: Dictionary of Labour Biography vol. XIII Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:24. Sep. 2021 Douglas Hyde (journalist and political activist) Douglas Arnold Hyde was born at Broadwater, Sussex on 8 April 1911. His family moved, first to Guildford, then to Bristol at the start of the First World War, and he was brought up on the edge of Durdham Downs. His father Gerald Hyde (1892-1968) was a master baker forced to take up waged work on the defection of a business partner. -

Singapore's Chinese-Speaking and Their Perspectives on Merger

Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, Volume 5, 2011-12 南方華裔研究雜志, 第五卷, 2011-12 “Flesh and Bone Reunite as One Body”: Singapore’s Chinese- speaking and their Perspectives on Merger ©2012 Thum Ping Tjin* Abstract Singapore’s Chinese speakers played the determining role in Singapore’s merger with the Federation. Yet the historiography is silent on their perspectives, values, and assumptions. Using contemporary Chinese- language sources, this article argues that in approaching merger, the Chinese were chiefly concerned with livelihoods, education, and citizenship rights; saw themselves as deserving of an equal place in Malaya; conceived of a new, distinctive, multiethnic Malayan identity; and rejected communist ideology. Meanwhile, the leaders of UMNO were intent on preserving their electoral dominance and the special position of Malays in the Federation. Finally, the leaders of the PAP were desperate to retain power and needed the Federation to remove their political opponents. The interaction of these three factors explains the shape, structure, and timing of merger. This article also sheds light on the ambiguity inherent in the transfer of power and the difficulties of national identity formation in a multiethnic state. Keywords: Chinese-language politics in Singapore; History of Malaya; the merger of Singapore and the Federation of Malaya; Decolonisation Introduction Singapore’s merger with the Federation of Malaya is one of the most pivotal events in the country’s history. This process was determined by the ballot box – two general elections, two by-elections, and a referendum on merger in four years. The centrality of the vote to this process meant that Singapore’s Chinese-speaking1 residents, as the vast majority of the colony’s residents, played the determining role. -

S/N MOE Schools 1 Admiralty Primary School 2 Admiralty Secondary School 3 Ahmad Ibrahim Primary School 4 Ahmad Ibrahim Second

S/N MOE Schools 1 Admiralty Primary School 2 Admiralty Secondary School 3 Ahmad Ibrahim Primary School 4 Ahmad Ibrahim Secondary School 1 Ai Tong School 2 Alexandra Primary School 3 Anchor Green Primary School 4 Anderson Primary School 5 Anderson Secondary School 6 Anderson Serangoon JC 7 Ang Mo Kio Primary School 8 Ang Mo Kio Secondary School 9 Anglican High (Secondary) 10 Anglo-Chinese Junior College 11 Anglo-Chinese Primary School (Barker Rd) 16 Anglo-Chinese School (Junior) 17 Anglo-Chinese Secondary School (Barker Rd) 18 Angsana Primary School 19 Assumption English School 20 Assumption Pathway School 21 Bartley Secondary School 22 Beacon Primary School 23 Beatty Secondary School 24 Bedok Green Primary School 25 Bedok Green Secondary School 26 Bedok South Secondary School 27 Bedok View Secondary School 28 Bendemeer Primary School 29 Bendemeer Secondary School 30 Blangah Rise Primary School 31 Boon Lay Garden Primary School 32 Boon Lay Secondary School 33 Bowen Secondary School 34 Broadrick Secondary School 35 Bukit Batok Secondary School 36 Bukit Merah Secondary School 37 Bukit Panjang Govt High School 38 Bukit Panjang Primary School 39 Bukit Timah Primary School 40 Bukit View Primary School 41 Bukit View Secondary School 42 Canberra Primary School 43 Canberra Secondary School 44 Canossa Catholic Primary School 45 Cantonment Primary School 46 Casuarina Primary School 47 Catholic High School (Primary) 48 Catholic High School (Secondary) 49 Catholic Junior College 50 Cedar Girls Secondary School 51 Cedar Primary School 52 Changi Coast -

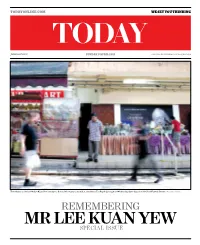

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

SPAFA Digest 1990, Vol 11, No. 3

39 (Symbolic Communication in Theatre: A Malaysian Chinese Case by Dr. Chua Soo Pong Theatrical event in Asian Examination of the details of the feelings of the Chinese community in societies has never been a purely structural processes in the artistic Malaysia. But they also reflect the artistic event. It usually has several production of the arts could locate awareness of the Chinese artistes in functions simultaneously. Subli in the specific issues in the wider social stating their inspiration to promote Philippines, Wayang Purwa in Java, context. Malay, Indian, and Chinese dance on Chinese opera in Singapore, Mayong This paper is based on personal equal footing. It is clear that the in Kelantan, or Lakorn Chatri in involvement as adjudicator in the Chinese artistes would prefer the art Thailand, all demonstrate the fact four dance festivals (1983, 1984, 1987, forms of the various ethnic groups to that theatrical events in the region 1989) organized by a number of be developed side by side with one serve a variety of political, social or Chinese cultural organizations in another. religious purposes much more expli- Malaysia and in the author's long citly than the art forms in the West. time observations and research on Gathering in Penang Anthropologists of the art and dance in Malaysia. In this article expressive culture have in recent years the author will focus on three areas. The last two days of 1983 have advanced their studies and proposed It provides an overview of the been most exciting for the dance several approaches in the analysis of festivals organized in the last few audience in Penang. -

Nhb13093018.Pdf

Annual Report 2012/2013 CONTENTS 2 Highlights for FY2012 14 Board Members 16 Corporate Information 17 Organisational Structure 18 Corporate Governance 20 Grants & Capability Development 24 Giving 32 Donations & Acquisitions 38 Publications FY2012 was an exciting year of new developments. On 1 November 2012, we came under a new ministry – the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth. Under the new ministry, we aspire 40 Financial Statements to deepen our conversations and engagements with various sectors. We will continue to nurture Statement by Board Members an appreciation for Singapore’s diverse and multicultural heritage and provide platforms for Independent Auditors’ Report community involvement. Financials A new family member, the Language Council joined the NHB family and we warmly welcome Notes to Financial Statements them. Language is closely linked to one’s heritage and the work that the LCS does will allow NHB to be more synergistic in our heritage offerings for Singaporeans. In FY2012, we launched several new initiatives. Of particular significance was the launch of Our Museum @ Taman Jurong – the first community museum in Singapore’s heartlands. The Malay Heritage Centre was re-opened with a renewed focus on Kampong Gelam, and the contributions of the local Malay community. The Asian Civilisations Museum also announced a new extension, which will allow for more of our National Collection to be displayed. Community engagement remained a priority as we stepped up our efforts to engage Singaporeans from all walks of life – heritage enthusiasts, corporations, interest groups, volunteer guides, patrons and many more, joined us in furthering the heritage cause. Their stories and memories were shared and incorporated into a wide range of offerings including community exhibitions and events, heritage trails, merchandise and e-books. -

One Party Dominance Survival: the Case of Singapore and Taiwan

One Party Dominance Survival: The Case of Singapore and Taiwan DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lan Hu Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor R. William Liddle Professor Jeremy Wallace Professor Marcus Kurtz Copyrighted by Lan Hu 2011 Abstract Can a one-party-dominant authoritarian regime survive in a modernized society? Why is it that some survive while others fail? Singapore and Taiwan provide comparable cases to partially explain this puzzle. Both countries share many similar cultural and developmental backgrounds. One-party dominance in Taiwan failed in the 1980s when Taiwan became modern. But in Singapore, the one-party regime survived the opposition’s challenges in the 1960s and has remained stable since then. There are few comparative studies of these two countries. Through empirical studies of the two cases, I conclude that regime structure, i.e., clientelistic versus professional structure, affects the chances of authoritarian survival after the society becomes modern. This conclusion is derived from a two-country comparative study. Further research is necessary to test if the same conclusion can be applied to other cases. This research contributes to the understanding of one-party-dominant regimes in modernizing societies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the Lord, Jesus Christ. “Counsel and sound judgment are mine; I have insight, I have power. By Me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just; by Me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth.” Proverbs 8:14-16 iii Acknowledgments I thank my committee members Professor R. -

Human Rights, Culture, and the Singapore Example

Human Rights, Culture, and the Singapore Example Simon S.C. Tay' Culture haunts the search fora system of human rights that La recherche d'un systame des droits de la personne rel- can truly be universal. Today, when we value cultural diversity, lement universel ne peut faire abstraction de la culture. Au- religious and regional factors have increasingly emerged as rea- jourd'hui, alors qu'est valoris6 la diversit6 culturelle, des facteurs sons for differences in human rights. In Asia, the main propo- religieux et rdgionaux apparaissent plus frdquemment pour crder nents for this cultural argument are governments representing des diffdrences en droit de la personne. En Asie, les partisans polyglot, largely multi-ethnic, modem capitalist societies. Singa- principaux de cet argument culturel sont des gouvemements qui porean representatives, dubbed "the Singapore school", have reprisentent des socidtds polyglottes, largement multi-ethniques, been prominent among them. These proponents say that Asian modemes et capitalistes. Parmi celles-ci, les representants de views and practices of human rights necessarily differ from those Singapour, sumomms .d' cle de Singapour jouent un rtle in the West because Asian culture differs. important. Ces partisans estiment que la notion et le respect des A closer look at the Singapore example demonstrates the droits de la personne en Asie diflgrent ndcessairement de reasons for which these characterizations may be rejected. The l'occident car la culture asiatique est diffdrente. 1996 CanLIIDocs 36 roots of Singaporean society are not originally and wholly Une 6tude plus approfondie de l'exemple de Singapour "Asian". Rather, they are a hybrid of colonial influences, includ- ddmontre les raisons pour lesquelles ces caractdrisations peuvent ing laws relating to fundamental civil and political liberties. -

Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singaporeâ

Law Text Culture Volume 18 The Rule of Law and the Cultural Article 10 Imaginary in (Post-)colonial East Asia 2014 Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law Jothie Rajah American Bar Foundation Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Rajah, Jothie, Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law, Law Text Culture, 18, 2014, 135-165. Available at:http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol18/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law Abstract One of the funny things about living in the United States is that people say to me: ‘Singapore? Isn’t that where they flog you for chewing gum?’ – and I am always tempted to say yes. This question reveals what sticks in the popular US cultural imaginary about tiny, faraway Singapore. It is based on two events: first, in 1992, the sale of chewing gum was banned (Sale of Food [Prohibition of Chewing Gum] Regulations 1992), and second, in 1994, 18 year-old US citizen, Michael Fay, convicted of vandalism for having spray-painted some cars was sentenced to six strokes of the cane (Michael Peter Fay v Public Prosecutor).1 If Singapore already had a reputation for being a nanny state, then these two events simultaneously sharpened that reputation and confused the stories into the composite image through which Americans situate Singaporeans. -

9789814677790 (.Pdf)

CONTRIBUTORS “Come to think of it, finally, it’s only friendship that matters.” Robert Kuok Lee Kuan Yew The idea for this book came about Yong Pung How in 2014. Liew Mun Leong and For ReviewUp Close Up only Close Othman Wok Ong Beng Seng were on a flight Puan Noor Aishah S.R. Nathan with back to Singapore and chatting J.Y. Pillay Up Close with about Mr Lee Kuan Yew, whom Lim Chin Beng they had known for many years. Wee Cho Yaw Lee Kuan Yew As they shared personal stories with Ch’ng Jit Koon Insights from colleagues and friends about their interactions with Sidek Saniff Lee Mr Lee, they felt it was time for Philip Yeo Lee Kuan Yew a book that told the personal side Jennie Chua Up Close with Lee Kuan Yew gathers some of the vivid about him. They broached the Liew Mun Leong memories of 37 people who have worked or interacted idea with Mr Lee on two separate Lim Siong Guan closely with Lee Kuan Yew in some way or other, from Jagjeet Singh dinner occasions; and when he when he was at Raffles College in 1941 right up to his Kuan Ng Kok Song gave his consent they formed demise in 2015. Among these are his 13 Principal Private Lam Chuan Leong a book committee comprising Secretaries and Special Assistants who lived and breathed Bilahari Kausikan Andrew Tan, Jennie Chua and Stephen Lee Mr Lee for a few years each, and Mdm Yeong Yoon Ying, Liew Mun Leong. Li Ka-shing his Press Secretary of over 20 years.