VERBAL ART PERFORMANCE in RAP MUSIC: the CONVERSATION of the 80'S Cheryl L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internet Killed the B-Boy Star: a Study of B-Boying Through the Lens Of

Internet Killed the B-boy Star: A Study of B-boying Through the Lens of Contemporary Media Dehui Kong Senior Seminar in Dance Fall 2010 Thesis director: Professor L. Garafola © Dehui Kong 1 B-Boy Infinitives To suck until our lips turned blue the last drops of cool juice from a crumpled cup sopped with spit the first Italian Ice of summer To chase popsicle stick skiffs along the curb skimming stormwater from Woodbridge Ave to Old Post Road To be To B-boy To be boys who snuck into a garden to pluck a baseball from mud and shit To hop that old man's fence before he bust through his front door with a lame-bull limp charge and a fist the size of half a spade To be To B-boy To lace shell-toe Adidas To say Word to Kurtis Blow To laugh the afternoons someone's mama was so black when she stepped out the car B-boy… that’s what it is, that’s why when the public the oil light went on changed it to ‘break-dancing’ they were just giving a To count hairs sprouting professional name to it, but b-boy was the original name for it and whoever wants to keep it real would around our cocks To touch 1 ourselves To pick the half-smoked keep calling it b-boy. True Blues from my father's ash tray and cough the gray grit - JoJo, from Rock Steady Crew into my hands To run my tongue along the lips of a girl with crooked teeth To be To B-boy To be boys for the ten days an 8-foot gash of cardboard lasts after we dragged that cardboard seven blocks then slapped it on the cracked blacktop To spin on our hands and backs To bruise elbows wrists and hips To Bronx-Twist Jersey version beside the mid-day traffic To swipe To pop To lock freeze and drop dimes on the hot pavement – even if the girls stopped watching and the street lamps lit buzzed all night we danced like that and no one called us home - Patrick Rosal 1 The Freshest Kids , prod. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

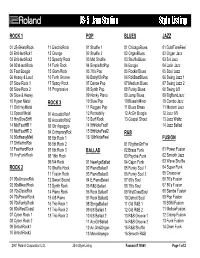

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

Outpouring of Support Keeps Restaurant Serving

The Charlotte Post THURSDAY,Li DECEMBERf 17,e 2020 SECTION! B Consortium aims to foster racial healing FAMOUS TOASTERY Justin and Kim Griffith, owners of a Famous Toastery franchise in Center City, rebounded from laying off 30 employees due to By Ashley Mahoney the pandemic when customers responded to their call to action in support of their Black-owned business. [email protected] Charlotte’s colleges are striving to rewrite the narrative around race. Johnson C. Smith University, Queens University and UNC Charlotte were awarded a $20,000 one-year Outpouring of support grant through the Association of American Colleges & Universities as a Truth, Racial Healing and Trans- formation Campus Center to create the Charlotte Ra- cial Justice Consortium. Johnson & Wales University and Central Piedmont Community College joined in keeps restaurant serving the summer. “It is our way as the academic institutions, which Customers step in to help Black-owned eatery weather the pandemic are cornerstones in the community, to rewrite the narrative around race in this city, to reimagine what By Ashley Mahoney you get to see the other side of it fiths selected an option on Yelp race can look like and to provide a [email protected] and coming back down to reality. that identified the restaurant as pathway for us to pull in other in- I lived in a world where when you Black-owned. Yelp sent a sticker, stitutions to begin creating that Justin Griffith knows how to get went to the airport you had police which they made visible on a win- On The Net change to create equity and ready for high-pressure situ- escorts and your hotels were dow and also posted on Instagram taken care of, but when March hit, https://diversity.unc true social justice across our ations, but 12 years in the Na- on June 4. -

Epsiode 20: Happy Birthday, Hybrid Theory!

Epsiode 20: Happy Birthday, Hybrid Theory! So, we’ve hit another milestone. I’ve rated for 15+ before like 6am, when it made 20 episodes of this podcast – which becomes a Top 50 countdown. When I was is frankly very silly – and I was trying younger, it was the quickest way to find to think about what I could write about new music, and potentially accidentally to reflect such a momentous occasion. see something that would really scar I was trying to think of something that you, music-video wise. Like that time I was released in the year 2000 and accidentally saw Aphex Twin’s Come to was, as such, experiencing a similarly Daddy music video. momentous 20th anniversary. The answer is, unsurprisingly, a lot of things But because I was tiny and my brain – Gladiator, Bring It On and American was a sponge, it turns out a lot of what Psycho all came out in the year 2000. But I consumed has actually just oozed into I wasn’t allowed to watch any of those every recess of my being, to the point things until I was in high school, and they where One Step Closer came on and I didn’t really spur me to action. immediately sang all the words like I was in some sort of trance. And I haven’t done And then I sent a rambling voice memo a musical episode for a while. So, today, to Wes, who you may remember from we’re talking Nu Metal, baby! Hell yeah! such hits as “making this podcast sound any good” and “writing the theme tune I’m Alex. -

South Bronx Environmental Health and Policy Study, Public Health and Environmental Policy Analysis: Final Report

SOUTH BRONX ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH AND POLICY STUDY Public Health and Environmental Policy Analysis Funded with a Congressional Appropriation sponsored by Congressman José E. Serrano and administered through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Environmental Planning, Zoning, Land Use, Air Quality and Public Health Final Report for Phase IV December 2007 Institute for Civil Infrastructure Systems (ICIS) Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service New York University 295 Lafayette Street New York, NY 10012 (212) 992ICIS (4247) www.nyu.edu/icis Edited by Carlos E. Restrepo and Rae Zimmerman 1 SOUTH BRONX ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH AND POLICY STUDY Public Health and Environmental Policy Analysis Funded with a Congressional Appropriation sponsored by Congressman José E. Serrano and administered through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Environmental Planning, Zoning, Land Use, Air Quality and Public Health Final Report for Phase IV December 2007 Edited by Carlos E. Restrepo and Rae Zimmerman Institute for Civil Infrastructure Systems (ICIS) Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service New York University 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1. Introduction 5 Chapter 2. Environmental Planning Frameworks and Decision Tools 9 Chapter 3. Zoning along the Bronx River 29 Chapter 4. Air Quality Monitoring, Spatial Location and Demographic Profiles 42 Chapter 5. Hospital Admissions for Selected Respiratory and Cardiovascular Diseases in Bronx County, New York 46 Chapter 6. Proximity Analysis to Sensitive Receptors using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) 83 Appendix A: Publications and Conferences featuring Phase IV work 98 3 This project is funded through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) by grant number 982152003 to New York University. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Hunts Point & Longwood Commercial District Needs Assessment

HUNTS POINT LONGWOOD THE BRONX Commercial District Needs Assessment COMMERCIAL DISTRICT NEEDS ASSESSMENT in partnership Greater Hunts Point Economic Development Corporation with ABOUT HUNTS POINT & LONGWOOD Background Avenue NYC is a competitive grant Located southeast of Southern Boulevard and the Bruckner Expressway, Hunts Point and Longwood program created by the NYC Department of Small Business comprise an estimated 2.2 square-mile area of the South Bronx. Hunts Point is a peninsula bordered Services to fund and build the by the East River to the south and southeast, the Bronx River to the east, and the Bruckner Expressway capacity of community-based to the north and west. From the 19th century until World War I, the neighborhood served as an elite development organizations to getaway destination for wealthy New York City families. The opening of the Pelham Bay Line (6 execute commercial revitalization initiatives. Avenue NYC is funded Train) along Southern Boulevard in 1920 allowed for a small residential core of working and middle- through the U.S. Department of class families to settle in Hunts Point. After World War II, large scale industrial businesses expanded Housing and Urban Development’s throughout the remaining peninsula in one and two-story warehouses and factory buildings. These Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Program, which types of businesses maintain a significant presence to this day in food wholesale, manufacturing, and targets investments in low- and automotive businesses within the Hunts Point Industrial -

Why Hip Hop Began in the Bronx- Lecture for C-Span

Fordham University DigitalResearch@Fordham Occasional Essays Bronx African American History Project 10-28-2019 Why Hip Hop Began in the Bronx- Lecture for C-Span Mark Naison Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_essays Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the Ethnomusicology Commons Why Hip Hop Began in the Bronx- My Lecture for C-Span What I am about to describe to you is one of the most improbable and inspiring stories you will ever hear. It is about how young people in a section of New York widely regarded as a site of unspeakable violence and tragedy created an art form that would sweep the world. It is a story filled with ironies, unexplored connections and lessons for today. And I am proud to share it not only with my wonderful Rock and Roll to Hip Hop class but with C-Span’s global audience through its lectures in American history series. Before going into the substance of my lecture, which explores some features of Bronx history which many people might not be familiar with, I want to explain what definition of Hip Hop that I will be using in this talk. Some people think of Hip Hop exclusively as “rap music,” an art form taken to it’s highest form by people like Tupac Shakur, Missy Elliot, JZ, Nas, Kendrick Lamar, Wu Tang Clan and other masters of that verbal and musical art, but I am thinking of it as a multilayered arts movement of which rapping is only one component. -

Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 12-14-2020 Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music Cervanté Pope Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Pope, Cervanté, "Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music" (2020). University Honors Theses. Paper 957. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.980 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music By Cervanté Pope Student ID #: 947767021 Portland State University Pope 2 Introduction In mass communication, gatekeeping refers to how information is edited, shaped and controlled in efforts to construct a “social reality” (Shoemaker, Eichholz, Kim, & Wrigley, 2001). Gatekeeping has expanded into other fields throughout the years, with its concepts growing more and more easily applicable in many other aspects of life. One way it presents itself is in regard to racial inclusion and equality, and despite the headway we’ve seemingly made as a society, we are still lightyears away from where we need to be. Because of this, the concept of cultural property has become even more paramount, as a means for keeping one’s cultural history and identity preserved. -

A Comparison of the Verbal Teaching Patterns of Two Groups of Secondary

A comparison of the verbal teaching patterns of two groups of secondary student teachers, Montana State University, 1969-70 by Dennis Larry Martinen A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree \ of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION in Secondary Education Montana State University © Copyright by Dennis Larry Martinen (1970) Abstract: The problem in this study was to investigate the verbal teaching patterns of secondary student teachers and to determine essentially what these teaching patterns were. As a corollary to the problem, the Rokeach Dogmatism Scale and the Teaching Situation Reaction Test were administered to student teachers to determine if these tests could predict successful student teachers prior to their student teaching experience in the secondary schools of Montana. It was the purpose of this study, then, to record and analyze the verbal behavior patterns of two groups of secondary student teachers. One group, the control group, consisted of students who went through the regular training program. The other group received twenty hours of training in interaction analysis. Selected aspects of the reconstructed Flanders' matrix were compared and analyzed. Another aspect of the problem dealt with the possible predictive value of the Teaching Situation Reaction Test and the Rokeach Dogmatism Scale as they pertained to superior teaching. A comparison and analysis was made between scores achieved on the two tests and such quantitative elements as grade point average in the major subject area, mean scores on the rating forms used by Montana State University supervisors and the grade given to measure the success in student teaching. -

Music 3500: American Music This Final Exam Is Comprehensive —It Covers the Entire Course (Monday December Starting at 5PM In

FINAL EXAM STUDY GUIDE Music 3500: American Music This final exam is comprehensive —it covers the entire course (Monday December starting at 5PM in Knauss Hall 2452) Exam Format: 70 questions (each question is worth 4 points), plus a 40-point "fill-in-the-chart" (described below) (these two things total a maximum of 320 possible points toward your final course grade total). The format of the 70-question computer-graded section of the final exam will be: ...Matching ...Multiple Choice ...True/False (from text readings, class lectures, YouTube video links) General study recommendations: - Do the online quiz assignments for Chapters 1-9 (these must be completed by Monday April 24) ---------- For the Computer-Graded part of the final exam: 1. Know the definitions of Important Terms at the ends of Chapters 2-8 - Chapter 1 (textbook, page 5) -- know "popular music," "roots music," "Classical art- music" - Chapter 2 (textbook, page 19) -- know "old-time music," "hot jazz," "race music" - Chapter 3 (textbook, page 31) -- know "bebop," "big-band," "boogie-woogie" - Chapter 4 (textbook, page 42) -- know "backbeat," "chance music," "cool jazz," "multi- serialism," "rhythm & blues," "soul" - Chapter 5 (textbook, page 52) -- know "soundtrack," "free jazz" - Chapter 6 (textbook, pages 58-59) -- know "fusion," minimalism," - Chapter 7 (textbook, pages 69-70) -- know "techno," "smooth jazz," "hip-hop" - Chapter 8 (textbook, page 81) -- know "sound art" 2. Know which decade the following music technologies came from: (Review the chronological order of