1 ZFP SPECIFICATIONS DOCUMENT MARCH 27, 2020 Zone Forecast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Precipitation Liquid–Ice Phase Transitions Revealed with Polarimetric Radar and 2DVD Observations in Central Oklahoma

MAY 2017 B U K O V CICETAL. 1345 Winter Precipitation Liquid–Ice Phase Transitions Revealed with Polarimetric Radar and 2DVD Observations in Central Oklahoma PETAR BUKOVCIC ´ NOAA/National Severe Storms Laboratory, and Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, and School of Meteorology, and Advanced Radar Research Center, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma DUSAN ZRNIC´ NOAA/National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma GUIFU ZHANG School of Meteorology, and Advanced Radar Research Center, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma (Manuscript received 30 June 2016, in final form 8 November 2016) ABSTRACT Observations and analysis of an ice–liquid phase precipitation event, collected with an S-band polarimetric KOUN radar and a two-dimensional video disdrometer (2DVD) in central Oklahoma on 20 January 2007, are presented. Using the disdrometer measurements, precipitation is classified either as ice pellets or rain/freezing rain. The disdrometer observations showed fast-falling and slow-falling particles of similar size. The vast majority (.99%) were fast falling with observed velocities close to those of raindrops with similar sizes. In contrast to the smaller particles (,1 mm in diameter), bigger ice pellets (.1.5 mm) were relatively easy to distinguish because their shapes differ from the raindrops. The ice pellets were challenging to detect by looking at conventional polarimetric radar data because of the localized and patchy nature of the ice phase and their occurrence close to the ground. Previously published findings referred to cases in which ice pellet areas were centered on the radar location and showed a ringlike structure of enhanced differential reflectivity ZDR and reduced copolar correlation coefficient rhv and horizontal reflectivity ZH in PPI images. -

Downloaded 10/01/21 08:52 PM UTC 186 WEATHER and FORECASTING VOLUME 16

FEBRUARY 2001 NOTES AND CORRESPONDENCE 185 Further Investigation of a Physically Based, Nondimensional Parameter for Discriminating between Locations of Freezing Rain and Ice Pellets ROBERT M. RAUBER,LARRY S. OLTHOFF, AND MOHAN K. RAMAMURTHY Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana±Champaign, Urbana, Illinois KENNETH E. KUNKEL Midwestern Climate Center, Illinois State Water Survey, Champaign, Illinois 9 December 1999 and 16 August 2000 ABSTRACT The general applicability of an isonomogram developed by Czys and coauthors to diagnose the position of the geographic boundary between freezing precipitation (freezing rain or freezing drizzle) and ice pellets (sleet or snow grains) was tested using a 25-yr sounding database consisting of 1051 soundings, 581 where stations were reporting freezing drizzle, 391 reporting freezing rain, and 79 reporting ice pellets. Of the 1051 soundings, only 306 clearly had an environmental temperature and moisture pro®le corresponding to that assumed for the isonomogram. This pro®le consisted of a three-layer atmosphere with 1) a cold cloud layer aloft that is a source of ice particles, 2) a midlevel layer where the temperature exceeds 08C and ice particles melt, and 3) a surface layer where T , 08C. The remaining soundings did not conform to the pro®le either because 1) the freezing precipitation was associated with the warm rain process or 2) the ice pellets formed due to riming rather than melting and refreezing. For soundings conforming to the pro®le, the isonomogram showed little diagnostic skill. Freezing rain or freezing drizzle occurred about 50% of the time that ice pellets were expected. -

Weather and Climate: Changing Human Exposures K

CHAPTER 2 Weather and climate: changing human exposures K. L. Ebi,1 L. O. Mearns,2 B. Nyenzi3 Introduction Research on the potential health effects of weather, climate variability and climate change requires understanding of the exposure of interest. Although often the terms weather and climate are used interchangeably, they actually represent different parts of the same spectrum. Weather is the complex and continuously changing condition of the atmosphere usually considered on a time-scale from minutes to weeks. The atmospheric variables that characterize weather include temperature, precipitation, humidity, pressure, and wind speed and direction. Climate is the average state of the atmosphere, and the associated characteristics of the underlying land or water, in a particular region over a par- ticular time-scale, usually considered over multiple years. Climate variability is the variation around the average climate, including seasonal variations as well as large-scale variations in atmospheric and ocean circulation such as the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) or the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Climate change operates over decades or longer time-scales. Research on the health impacts of climate variability and change aims to increase understanding of the potential risks and to identify effective adaptation options. Understanding the potential health consequences of climate change requires the development of empirical knowledge in three areas (1): 1. historical analogue studies to estimate, for specified populations, the risks of climate-sensitive diseases (including understanding the mechanism of effect) and to forecast the potential health effects of comparable exposures either in different geographical regions or in the future; 2. studies seeking early evidence of changes, in either health risk indicators or health status, occurring in response to actual climate change; 3. -

News and Notes

346 BULLETIN AMERICAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY NEWS AND NOTES Air Force Scientists Develop Technique The feasibility of dissipating supercooled clouds by for Cutting Holes in "Cold" Clouds seeding with dry-ice was recognized many years ago. Airborne equipment, previously developed to do this, A new technique for creating holes in supercooled cloud crushed large blocks of dry-ice into particles suitable for layers has been developed by Air Force Cambridge Re- seeding purposes. search Laboratories scientists. During recent flight tests This equipment had two particular limitations. First, using this technique, holes more than 3 miles wide were these machines produced about half powdered dry-ice created in supercooled clouds. which evaporated immediately upon dispersal from the Major James F. Church, project scientist in AFCRL's aircraft and was wasted. Second, the logistical problem Meteorological Research Laboratory is directing research of supplying enough dry-ice where needed and the high on the dissipation of supercooled stratiform clouds. The evaporational losses suffered during storage until used, program is under the technical management of the Air severely limited the utility of this technique. Force System Command's Electronic Systems Division. The Cloudbuster makes ice pellets by passing liquid The principal objective of this research is to provide C02 through an expansion nozzle and then compacting Air Force cargo and transport pilots with an economical the solid dry-ice powder, which is then formed, into proper capability to seed supercooled clouds with dry-ice pellets, size. The Cloudbuster has been designed with the capa- made on the aircraft and dispersed at will, to create bility of making different-sized pellets at the touch of a sizable holes in such cloud decks. -

Articles from Bon, Inorganic Aerosol and Sea Salt

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 6585–6599, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-6585-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Meteorological controls on atmospheric particulate pollution during hazard reduction burns Giovanni Di Virgilio1, Melissa Anne Hart1,2, and Ningbo Jiang3 1Climate Change Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2052, Australia 2Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2052, Australia 3New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney, 2000, Australia Correspondence: Giovanni Di Virgilio ([email protected]) Received: 22 May 2017 – Discussion started: 28 September 2017 Revised: 22 January 2018 – Accepted: 21 March 2018 – Published: 8 May 2018 Abstract. Internationally, severe wildfires are an escalating build-up of PM2:5. These findings indicate that air pollution problem likely to worsen given projected changes to climate. impacts may be reduced by altering the timing of HRBs by Hazard reduction burns (HRBs) are used to suppress wild- conducting them later in the morning (by a matter of hours). fire occurrences, but they generate considerable emissions Our findings support location-specific forecasts of the air of atmospheric fine particulate matter, which depend upon quality impacts of HRBs in Sydney and similar regions else- prevailing atmospheric conditions, and can degrade air qual- where. ity. Our objectives are to improve understanding of the re- lationships between meteorological conditions and air qual- ity during HRBs in Sydney, Australia. We identify the pri- mary meteorological covariates linked to high PM2:5 pollu- 1 Introduction tion (particulates < 2.5 µm in diameter) and quantify differ- ences in their behaviours between HRB days when PM2:5 re- Many regions experience regular wildfires with the poten- mained low versus HRB days when PM2:5 was high. -

Quantifying the Impact of Synoptic Weather Types and Patterns On

1 Quantifying the impact of synoptic weather types and patterns 2 on energy fluxes of a marginal snowpack 3 Andrew Schwartz1, Hamish McGowan1, Alison Theobald2, Nik Callow3 4 1Atmospheric Observations Research Group, University of Queensland, Brisbane, 4072, Australia 5 2Department of Environment and Science, Queensland Government, Brisbane, 4000, Australia 6 3School of Agriculture and Environment, University of Western Australia, Perth, 6009, Australia 7 8 Correspondence to: Andrew J. Schwartz ([email protected]) 9 10 Abstract. 11 Synoptic weather patterns are investigated for their impact on energy fluxes driving melt of a marginal snowpack 12 in the Snowy Mountains, southeast Australia. K-means clustering applied to ECMWF ERA-Interim data identified 13 common synoptic types and patterns that were then associated with in-situ snowpack energy flux measurements. 14 The analysis showed that the largest contribution of energy to the snowpack occurred immediately prior to the 15 passage of cold fronts through increased sensible heat flux as a result of warm air advection (WAA) ahead of the 16 front. Shortwave radiation was found to be the dominant control on positive energy fluxes when individual 17 synoptic weather types were examined. As a result, cloud cover related to each synoptic type was shown to be 18 highly influential on the energy fluxes to the snowpack through its reduction of shortwave radiation and 19 reflection/emission of longwave fluxes. As single-site energy balance measurements of the snowpack were used 20 for this study, caution should be exercised before applying the results to the broader Australian Alps region. 21 However, this research is an important step towards understanding changes in surface energy flux as a result of 22 shifts to the global atmospheric circulation as anthropogenic climate change continues to impact marginal winter 23 snowpacks. -

METAR/SPECI Reporting Changes for Snow Pellets (GS) and Hail (GR)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION N JO 7900.11 NOTICE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Effective Date: Air Traffic Organization Policy September 1, 2018 Cancellation Date: September 1, 2019 SUBJ: METAR/SPECI Reporting Changes for Snow Pellets (GS) and Hail (GR) 1. Purpose of this Notice. This Notice coincides with a revision to the Federal Meteorological Handbook (FMH-1) that was effective on November 30, 2017. The Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research (OFCM) approved the changes to the reporting requirements of small hail and snow pellets in weather observations (METAR/SPECI) to assist commercial operators in deicing operations. 2. Audience. This order applies to all FAA and FAA-contract weather observers, Limited Aviation Weather Reporting Stations (LAWRS) personnel, and Non-Federal Observation (NF- OBS) Program personnel. 3. Where can I Find This Notice? This order is available on the FAA Web site at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications and http://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices/. 4. Cancellation. This notice will be cancelled with the publication of the next available change to FAA Order 7900.5D. 5. Procedures/Responsibilities/Action. This Notice amends the following paragraphs and tables in FAA Order 7900.5. Table 3-2: Remarks Section of Observation Remarks Section of Observation Element Paragraph Brief Description METAR SPECI Volcanic eruptions must be reported whenever first noted. Pre-eruption activity must not be reported. (Use Volcanic Eruptions 14.20 X X PIREPs to report pre-eruption activity.) Encode volcanic eruptions as described in Chapter 14. Distribution: Electronic 1 Initiated By: AJT-2 09/01/2018 N JO 7900.11 Remarks Section of Observation Element Paragraph Brief Description METAR SPECI Whenever tornadoes, funnel clouds, or waterspouts begin, are in progress, end, or disappear from sight, the event should be described directly after the "RMK" element. -

The Mesoscale Dynamics of Freezing Rain Storms Over Eastern Canada

VOL. 56, NO.10 JOURNAL OF THE ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCES 15 MAY 1999 The Mesoscale Dynamics of Freezing Rain Storms over Eastern Canada K. K. SZETO Climate Processes and Earth Observation Division, Atmospheric Environment Service, Downsview, Ontario, Canada A. TREMBLAY Cloud Physics Research Division, Atmospheric Environment Service, Dorval, Quebec, Canada H. GUAN AND D. R. HUDAK Cloud Physics Research Division, Atmospheric Environment Service, Downsview, Ontario, Canada R. E. STEWART AND Z. CAO Climate Processes and Earth Observation Division, Atmospheric Environment Service, Downsview, Ontario, Canada (Manuscript received 2 June 1997, in ®nal form 9 June 1998) ABSTRACT A severe ice storm affected the east coast of Canada during the Canadian Atlantic Storms Project II. A hierarchy of cloud-resolving model simulations of this storm was performed with the objective of enhancing understanding of the cloud and mesoscale processes that affected the development of freezing rain events. The observed features of the system were reasonably well replicated in the high-resolution simulation. Diagnosis of the model results suggests that the change of surface characteristics from ocean to land when the surface warm front approaches Newfoundland disturbs the (quasi-) thermal wind balance near the frontal region. The cross-frontal circulation intensi®es in response to the thermal wind imbalance, which in turn leads to the development of an extensive above-freezing inversion layer in the model storm. Depending on the depth of the subfreezing layer below the inversion, the melted snow may refreeze within the subfreezing layer to form ice pellets or they may refreeze at the surface to form freezing rain. Such evolution of surface precipitation types in the model storm was reasonably well simulated in the model. -

Taking the Guesswork out of Lightning-Caused Wildfire Marjie Brown US Forest Service, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln JFSP Briefs U.S. Joint Fire Science Program 2008 Taking the Guesswork Out of Lightning-caused Wildfire Marjie Brown US Forest Service, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jfspbriefs Part of the Forest Biology Commons, Forest Management Commons, Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons, and the Wood Science and Pulp, Paper Technology Commons Brown, Marjie, "Taking the Guesswork Out of Lightning-caused Wildfire" (2008). JFSP Briefs. 23. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jfspbriefs/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Joint Fire Science Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in JFSP Briefs by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Lightning and fi re smoke. Taking the Guesswork Out of Lightning-caused Wildfi re Summary Lightning is a natural source of wildfi re ignitions and causes a substantial portion of large wildfi res across the globe. Simple predictions of lightning activity don’t accurately determine fi re ignition potential because fuel conditions must be considered in addition to the fact that most lightning is accompanied by signifi cant rain. Fire operations managers need improved tools for prediction of widespread dry thunderstorms, which are those that occur without signifi cant rainfall reaching the ground. It is these dry storms that generate lightning most likely to result in multiple fi re ignitions, often in remote areas. In previous work the researchers developed a formula that estimates the potential for cloud- to-ground lightning when dry thunderstorms are expected. -

CLOUD FRACTION: CAN IT BE DEFINED and MEASURED? and IF WE KNEW IT WOULD IT BE of ANY USE to US? Stephen E

CLOUD FRACTION: CAN IT BE DEFINED AND MEASURED? AND IF WE KNEW IT WOULD IT BE OF ANY USE TO US? Stephen E. Schwartz Upton NY USA Cloud Properties, Observations, and their Uncertainties www.bnl.gov/envsci/schwartz CLOUD FRACTION: CAN IT BE DEFINED AND MEASURED? AND IF WE KNEW IT WOULD IT BE OF ANY USE TO US? CONCLUSIONS No. No. No. I come to bury cloud fraction, not to praise it. - Shakespeare, 1599 WHAT IS A CLOUD? AMS Glossary of Meteorology (2000) A visible aggregate of minute water droplets and/or ice particles in the atmosphere above the earth’s surface. Total cloud cover: Fraction of the sky hidden by all visible clouds. Clothiaux, Barker, & Korolev (2005) Surprisingly, and in spite of the fact that we deal with clouds on a daily basis, to date there is no universal definition of a cloud. Ultimately, the definition of a cloud depends on the threshold sensitivity of the instruments used. Ramanathan, JGR (ERBE, 1988) Cloud cover is a loosely defined term. Potter Stewart (U.S. Supreme Court, 1964) I shall not today attempt further to define it, but I know it when I see it. WHY DO WE WANT TO KNOW CLOUD FRACTION, ANYWAY? Clouds have a strong impact on Earth’s radiation budget: -45 W m-2 shortwave; +30 W m-2 longwave. Slight change in cloud fraction could augment or offset greenhouse gas induced warming – cloud feedbacks. Getting cloud fraction “right” is an evaluation criterion for global climate models. Domain Observations Cloud cover Millions % Land 116 52.4 Ocean 43.3 64.8 Global 159 61.2 Warren, Hahn, London, Chervin, Jenne CLOUD FRACTION BY MULTIPLE METHODS 2 Surface, 3 satellite methods at U.S. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

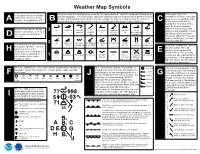

Print Key. (Pdf)

Weather Map Symbols Along the center, the cloud types are indicated. The top symbol is the high-level cloud type followed by the At the upper right is the In the upper left, the temperature mid-level cloud type. The lowest symbol represents low-level cloud over a number which tells the height of atmospheric pressure reduced to is plotted in Fahrenheit. In this the base of that cloud (in hundreds of feet) In this example, the high level cloud is Cirrus, the mid-level mean sea level in millibars (mb) A example, the temperature is 77°F. B C C to the nearest tenth with the cloud is Altocumulus and the low-level clouds is a cumulonimbus with a base height of 2000 feet. leading 9 or 10 omitted. In this case the pressure would be 999.8 mb. If the pressure was On the second row, the far-left Ci Dense Ci Ci 3 Dense Ci Cs below Cs above Overcast Cs not Cc plotted as 024 it would be 1002.4 number is the visibility in miles. In from Cb invading 45° 45°; not Cs ovcercast; not this example, the visibility is sky overcast increasing mb. When trying to determine D whether to add a 9 or 10 use the five miles. number that will give you a value closest to 1000 mb. 2 As Dense As Ac; semi- Ac Standing Ac invading Ac from Cu Ac with Ac Ac of The number at the lower left is the a/o Ns transparent Lenticularis sky As / Ns congestus chaotic sky Next to the visibility is the present dew point temperature.