Quantifying the Impact of Synoptic Weather Types and Patterns On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weather and Climate: Changing Human Exposures K

CHAPTER 2 Weather and climate: changing human exposures K. L. Ebi,1 L. O. Mearns,2 B. Nyenzi3 Introduction Research on the potential health effects of weather, climate variability and climate change requires understanding of the exposure of interest. Although often the terms weather and climate are used interchangeably, they actually represent different parts of the same spectrum. Weather is the complex and continuously changing condition of the atmosphere usually considered on a time-scale from minutes to weeks. The atmospheric variables that characterize weather include temperature, precipitation, humidity, pressure, and wind speed and direction. Climate is the average state of the atmosphere, and the associated characteristics of the underlying land or water, in a particular region over a par- ticular time-scale, usually considered over multiple years. Climate variability is the variation around the average climate, including seasonal variations as well as large-scale variations in atmospheric and ocean circulation such as the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) or the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Climate change operates over decades or longer time-scales. Research on the health impacts of climate variability and change aims to increase understanding of the potential risks and to identify effective adaptation options. Understanding the potential health consequences of climate change requires the development of empirical knowledge in three areas (1): 1. historical analogue studies to estimate, for specified populations, the risks of climate-sensitive diseases (including understanding the mechanism of effect) and to forecast the potential health effects of comparable exposures either in different geographical regions or in the future; 2. studies seeking early evidence of changes, in either health risk indicators or health status, occurring in response to actual climate change; 3. -

Articles from Bon, Inorganic Aerosol and Sea Salt

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 6585–6599, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-6585-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Meteorological controls on atmospheric particulate pollution during hazard reduction burns Giovanni Di Virgilio1, Melissa Anne Hart1,2, and Ningbo Jiang3 1Climate Change Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2052, Australia 2Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2052, Australia 3New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney, 2000, Australia Correspondence: Giovanni Di Virgilio ([email protected]) Received: 22 May 2017 – Discussion started: 28 September 2017 Revised: 22 January 2018 – Accepted: 21 March 2018 – Published: 8 May 2018 Abstract. Internationally, severe wildfires are an escalating build-up of PM2:5. These findings indicate that air pollution problem likely to worsen given projected changes to climate. impacts may be reduced by altering the timing of HRBs by Hazard reduction burns (HRBs) are used to suppress wild- conducting them later in the morning (by a matter of hours). fire occurrences, but they generate considerable emissions Our findings support location-specific forecasts of the air of atmospheric fine particulate matter, which depend upon quality impacts of HRBs in Sydney and similar regions else- prevailing atmospheric conditions, and can degrade air qual- where. ity. Our objectives are to improve understanding of the re- lationships between meteorological conditions and air qual- ity during HRBs in Sydney, Australia. We identify the pri- mary meteorological covariates linked to high PM2:5 pollu- 1 Introduction tion (particulates < 2.5 µm in diameter) and quantify differ- ences in their behaviours between HRB days when PM2:5 re- Many regions experience regular wildfires with the poten- mained low versus HRB days when PM2:5 was high. -

CLOUD FRACTION: CAN IT BE DEFINED and MEASURED? and IF WE KNEW IT WOULD IT BE of ANY USE to US? Stephen E

CLOUD FRACTION: CAN IT BE DEFINED AND MEASURED? AND IF WE KNEW IT WOULD IT BE OF ANY USE TO US? Stephen E. Schwartz Upton NY USA Cloud Properties, Observations, and their Uncertainties www.bnl.gov/envsci/schwartz CLOUD FRACTION: CAN IT BE DEFINED AND MEASURED? AND IF WE KNEW IT WOULD IT BE OF ANY USE TO US? CONCLUSIONS No. No. No. I come to bury cloud fraction, not to praise it. - Shakespeare, 1599 WHAT IS A CLOUD? AMS Glossary of Meteorology (2000) A visible aggregate of minute water droplets and/or ice particles in the atmosphere above the earth’s surface. Total cloud cover: Fraction of the sky hidden by all visible clouds. Clothiaux, Barker, & Korolev (2005) Surprisingly, and in spite of the fact that we deal with clouds on a daily basis, to date there is no universal definition of a cloud. Ultimately, the definition of a cloud depends on the threshold sensitivity of the instruments used. Ramanathan, JGR (ERBE, 1988) Cloud cover is a loosely defined term. Potter Stewart (U.S. Supreme Court, 1964) I shall not today attempt further to define it, but I know it when I see it. WHY DO WE WANT TO KNOW CLOUD FRACTION, ANYWAY? Clouds have a strong impact on Earth’s radiation budget: -45 W m-2 shortwave; +30 W m-2 longwave. Slight change in cloud fraction could augment or offset greenhouse gas induced warming – cloud feedbacks. Getting cloud fraction “right” is an evaluation criterion for global climate models. Domain Observations Cloud cover Millions % Land 116 52.4 Ocean 43.3 64.8 Global 159 61.2 Warren, Hahn, London, Chervin, Jenne CLOUD FRACTION BY MULTIPLE METHODS 2 Surface, 3 satellite methods at U.S. -

Print Key. (Pdf)

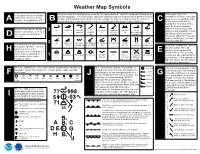

Weather Map Symbols Along the center, the cloud types are indicated. The top symbol is the high-level cloud type followed by the At the upper right is the In the upper left, the temperature mid-level cloud type. The lowest symbol represents low-level cloud over a number which tells the height of atmospheric pressure reduced to is plotted in Fahrenheit. In this the base of that cloud (in hundreds of feet) In this example, the high level cloud is Cirrus, the mid-level mean sea level in millibars (mb) A example, the temperature is 77°F. B C C to the nearest tenth with the cloud is Altocumulus and the low-level clouds is a cumulonimbus with a base height of 2000 feet. leading 9 or 10 omitted. In this case the pressure would be 999.8 mb. If the pressure was On the second row, the far-left Ci Dense Ci Ci 3 Dense Ci Cs below Cs above Overcast Cs not Cc plotted as 024 it would be 1002.4 number is the visibility in miles. In from Cb invading 45° 45°; not Cs ovcercast; not this example, the visibility is sky overcast increasing mb. When trying to determine D whether to add a 9 or 10 use the five miles. number that will give you a value closest to 1000 mb. 2 As Dense As Ac; semi- Ac Standing Ac invading Ac from Cu Ac with Ac Ac of The number at the lower left is the a/o Ns transparent Lenticularis sky As / Ns congestus chaotic sky Next to the visibility is the present dew point temperature. -

Composite VORTEX2 Supercell Environments from Near-Storm Soundings

508 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 142 Composite VORTEX2 Supercell Environments from Near-Storm Soundings MATTHEW D. PARKER Department of Marine, Earth, and Atmospheric Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina (Manuscript received 23 May 2013, in final form 29 August 2013) ABSTRACT Three-dimensional composite analyses using 134 soundings from the second Verification of the Origins of Rotation in Tornadoes Experiment (VORTEX2) reveal the nature of near-storm variability in the envi- ronments of supercell thunderstorms. Based upon the full analysis, it appears that vertical wind shear in- creases as one approaches a supercell within the inflow sector, providing favorable conditions for supercell maintenance (and possibly tornado formation) despite small amounts of low-level cooling near the storm. The seven analyzed tornadic supercells have a composite environment that is clearly more impressive (in terms of widely used metrics) than that of the five analyzed nontornadic supercells, including more convective available potential energy (CAPE), more vertical wind shear, higher boundary layer relative humidity, and lower tropospheric horizontal vorticity that is more streamwise in the near-storm inflow. The widely used supercell composite parameter (SCP) and significant tornado parameter (STP) summarize these differences well. Comparison of composite environments from early versus late in supercells’ lifetimes reveals only subtle signs of storm-induced environmental modification, but potentially important changes associated with the evening transition toward a cooler and moister boundary layer with enhanced low-level vertical shear. Finally, although this study focused primarily on the composite inflow environment, it is intriguing that the outflows sampled by VORTEX2 soundings were surprisingly shallow (generally #500 m deep) and retained consid- 2 erable CAPE (generally $1000 J kg 1). -

The Interactions Between a Midlatitude Blocking Anticyclone and Synoptic-Scale Cyclones That Occurred During the Summer Season

502 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 126 NOTES AND CORRESPONDENCE The Interactions between a Midlatitude Blocking Anticyclone and Synoptic-Scale Cyclones That Occurred during the Summer Season ANTHONY R. LUPO AND PHILLIP J. SMITH Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 20 September 1996 and 2 May 1997 ABSTRACT Using the Goddard Laboratory for Atmospheres Goddard Earth Observing System 5-yr analyses and the Zwack±Okossi equation as the diagnostic tool, the horizontal distribution of the dynamic and thermodynamic forcing processes contributing to the maintenance of a Northern Hemisphere midlatitude blocking anticyclone that occurred during the summer season were examined. During the development of this blocking anticyclone, vorticity advection, supported by temperature advection, forced 500-hPa height rises at the block center. Vorticity advection and vorticity tilting were also consistent contributors to height rises during the entire life cycle. Boundary layer friction, vertical advection of vorticity, and ageostrophic vorticity tendencies (during decay) consistently opposed block development. Additionally, an analysis of this blocking event also showed that upstream precursor surface cyclones were not only important in block development but in block maintenance as well. In partitioning the basic data ®elds into their planetary-scale (P) and synoptic-scale (S) components, 500-hPa height tendencies forced by processes on each scale, as well as by interactions (I) between each scale, were also calculated. Over the lifetime of this blocking event, the S and P processes were most prominent in the blocked region. During the formation of this block, the I component was the largest and most consistent contributor to height rises at the center point. -

Mesoscale Convective Systems and Their Synoptic-Scale Environment in Finland

182 WEATHER AND FORECASTING VOLUME 30 Mesoscale Convective Systems and Their Synoptic-Scale Environment in Finland ARI-JUHANI PUNKKA Finnish Meteorological Institute, Helsinki, Finland MARJA BISTER Division of Atmospheric Sciences, Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland (Manuscript received 9 December 2013, in final form 14 October 2014) ABSTRACT The environments within which high-latitude intense and nonintense mesoscale convective systems (iMCSs and niMCSs) and smaller thunderstorm clusters (sub-MCSs) develop were studied using proximity soundings. MCS statistics covering 8 years were created by analyzing composite radar imagery. One-third of all systems were intense in Finland and the frequency of MCSs was highest in July. On average, MCSs had a duration of 10.8 h and traveled toward the northeast. Many of the linear MCSs had a southwest–northeast line orienta- tion. Interestingly, a few MCSs were observed to travel toward the west, which is a geographically specific feature of the MCS characteristics. The midlevel lapse rate failed to distinguish the environments of the different event types from each other. However, in MCSs, CAPE and the low-level mixing ratio were higher, the deep-layer-mean wind was stronger, and the lifting condensation level (LCL) was lower than in sub- MCSs. CAPE, low-level mixing ratio, and LCL height were the best discriminators between iMCSs and niMCSs. The mean wind over deep layers distinguished the severe wind–producing events from the nonsevere events better than did the vertical equivalent potential temperature difference or the wind shear in shallow layers. No evidence was found to support the hypothesis that dry air at low- and midlevels would increase the likelihood of severe convective winds. -

Using GOES Imagery on AWIPS to Determine Cloud Cover and Snow Cover Kevin J

Using GOES imagery on AWIPS to determine cloud cover and snow cover Kevin J. Schrab WRSSD This TAlite will show how AWIPS can be used to determine cloud cover and snow cover. A 4panel image of VIS, IR, fog/refl/IR, and fog/refl from 18z on 18 Feb 2000 shows many interesting features. The VIS clearly depicts bare ground (Snake River plain and western Utah, for example). However, over much of the area it is difficult to distinguish between snow cover and cloud cover. This determination will obviously have a big impact on the public and aviation forecasts. The IR imagery (upper right panel) is not much help in differentiating snow cover from clouds. The fog/reflectivity product (lower right panel) clearly shows water clouds (white areas) over SE Montana, much of Wyoming, E Idaho, and NE Utah. The areas that are white in the VIS imagery and dark in the fog/reflectivity product imagery are snow cover (much of NE Montana, central Montana, portions of W Wyoming, and central Idaho). Fading between the VIS and fog/reflectivity product (toggle on AWIPS) clearly defines the cloud covered areas. Of course, we do not know if the water clouds identified by the fog/reflectivty product are fog or stratus. So, surface observations are important to determine the cloud type. At 18Z we see that some of the small cloud patches are fog and some are stratus. It is also interesting to note that some of the METARs show cloud cover, yet the cloud cover is just a small patch of clouds near the METAR site and that surrounding areas are clear. -

Intense Cold Wave of February 2011 Mike Hardiman, Forecaster, National Weather Service El Paso, TX / Santa Teresa, NM

Intense Cold Wave of February 2011 Mike Hardiman, Forecaster, National Weather Service El Paso, TX / Santa Teresa, NM Synopsis On Tuesday, February 1st, 2011, an intense arctic air mass moved into southern New Mexico and Far West Texas, while an upper-level trough moved in from the north. The system brought locally heavy snowfall to portions of the area on the night of Feb 1st and into the afternoon of the 2nd, and was followed by several days of sub-freezing temperatures. Temperatures in El Paso rose no higher than the upper 10s (°F) on February 2nd and 3rd. The prolonged cold weather caused widespread failures of infrastructure. Water and Gas utilities suffered from broken pipes and mains, with water leaks flooding several homes. At El Paso Electric, all eight primary power generators failed due to freezing conditions. While energy was brought into the area from elsewhere on the grid, rolling blackouts were implemented during peak electric use hours. Even as temperatures warmed up, water shortages continued to affect the El Paso and Sunland Park areas, as failed pumps caused reservoirs to quickly dry up. Meteorological Summary On Sunday, January 30th, a strong and sharply-defined upper level high pressure ridge was building across western Canada into the Arctic Ocean [Figure 1]. Northerly flow to the east of the Ridge allowed cold air from the polar regions to begin flowing south into the Yukon and Northwest Territories. By the next morning, temperatures in the -30 and -40s (°F) were common across northern Alberta and Saskatchewan, under a strengthening 1048 millibar (mb) surface high. -

An Empirical Note on Weather Effects in the Australian Stock Market

An empirical note on weather effects in the Australian stock market Author Worthington, Andrew Published 2009 Journal Title Economic Papers DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-3441.2009.00014.x Copyright Statement © 2009 The Economic Society of Australia. Published by Blackwell Publishing. This is the pre-peer reviewed version of the following article: Economic Papers Vol. 28, No. 2, June, 2009, 148–154 which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ j.1759-3441.2009.00014.x Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/30698 Link to published version http://www.interscience.wiley.com/jpages/0812-0439 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au AN EMPIRICAL NOTE ON WEATHER EFFECTS IN THE AUSTRALIAN STOCK MARKET ABSTRACT The behavioural finance literature posits a link between the weather and equity markets via investor moods. This paper examines the impact of weather on the Australian stock market over the period 1958 to 2005. A regression-based approach is employed where daily market returns on the Australian Securities Exchange’s All Ordinaries price index are regressed against eight daily weather observations (precipitation, evaporation, relative humidity, maximum and minimum temperature, hours of bright sunshine, and the speed and direction of the maximum wind gust) at Sydney’s Observatory Hill and Airport meteorological stations. Consistent with studies elsewhere including the Australian market, the results indicate that the weather has absolutely no influence on market returns. Some directions for future research that may help address some of the deficiencies found in this intriguing body of work are provided. -

A High-Quality Monthly Total Cloud Amount Dataset for Australia

Climatic Change (2011) 108:485–517 DOI 10.1007/s10584-010-9992-5 A high-quality monthly total cloud amount dataset for Australia Branislava Jovanovic · Dean Collins · Karl Braganza · Doerte Jakob · David A. Jones Received: 11 May 2009 / Accepted: 5 November 2010 / Published online: 16 December 2010 © The Author(s) 2010. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract A high-quality monthly total cloud amount dataset for 165 stations has been developed for monitoring and assessing long-term trends in cloud cover over Australia. The dataset is based on visual 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. observations of total cloud amount, with most records starting around 1957. The quality control process involved examination of historical station metadata, together with an objective statistical test comparing candidate and reference cloud series. Individual cloud series were also compared against rainfall and diurnal temperature range series from the same site, and individual cloud series from neighboring sites. Adjustments for inhomogeneities caused by relocations and changes in observers were applied, as well as adjustments for biases caused by the shift to daylight saving time in the summer months. Analysis of these data reveals that the Australian mean annual total cloud amount is characterised by high year-to-year variability and shows a weak, statistically non-significant increase over the 1957–2007 period. A more pronounced, but also non-significant, decrease from 1977 to 2007 is evident. A strong positive correlation is found between all-Australian averages of cloud amount and rainfall, while a strong negative correlation is found between mean cloud amount and diurnal temperature range. -

Analyzing the Probability of Acquiring Cloud-Free Imagery in China with AVHRR Cloud Mask Data

atmosphere Article Analyzing the Probability of Acquiring Cloud-Free Imagery in China with AVHRR Cloud Mask Data Yingjie Wu 1 , Shibo Fang 1,2,*, Yi Xu 3, Lei Wang 1, Xuan Li 1, Zhifang Pei 1 and Dong Wu 1 1 State Key Laboratory of Sever Weather, Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Beijing 100081, China; [email protected] (Y.W.); [email protected] (L.W.); [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (Z.P.); [email protected] (D.W.) 2 Collaborative Innovation Center on Forecast and Evaluation of Meteorological Disasters, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing 210044, China 3 Key Laboratory for Geo-Environmental Monitoring of Coastal Zone of the Ministry of Natural Resources & Guangdong Key Laboratory of Urban Informatics, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Optical remote sensing data are used widely in many fields (such as agriculture, resource management and the environment), especially for the vast territory of China; however, the application of these data is usually limited by clouds. Although it is valuable to analyze the probability of acquiring cloud-free imagery (PACI), PACI using different sensors at the pixel level across China has not been reported. In this study, the PACI of China was calculated with daily Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) cloud mask data from 1990 to 2019. The results showed that (1) PACI varies dramatically in different regions and months in China. The value was larger in autumn and winter, and the largest figure reached 49.55% in October in Inner Mongolia (NM).