Chapter Seven the Beiping Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Research Status of the Storm Society

International Journal of Science Vol.2 No.12 2015 ISSN: 1813-4890 On the Research Status of the Storm Society Hao Xing School of history, Hebei University, Baoding 071002, China [email protected] Abstract The Storm Society is the first well-organized art association, which consciously absorb the western modern art achievements in Chinese modern art history. Based on the historical materials, this paper describes the basic facts of the Storm Society, and analyze the research status and weakness of this organization, and summarizes its historical and practical significance in the transformation of Chinese art from traditional form to modern form. Keywords the Storm Society, Art Magazine, research status. 1. The Basic Facts of the Storm Society The Storm Society is brewed in 1930. Its predecessor is "moss Mongolia", which is a painting group organized by Xunqin Pang, but it is soon seized. Xunqin Pang says,”I feel deeply distressed that the spirit of Chinese art and literature is decaying and corrupting, but my shallow knowledge and ability is not enough to pull the decadent a little. So I decide to gather some comrades to strive for the hope of making some contribution to the world together. This is the origin of the Storm Society.” The Storm Society is established in Nanjing in 1931, aiming at probing and developing China’s oil painting art. The main sponsors of the group are Xunqin Pang,Yide Ni , Jiyuan Wang , Zhentai Zhou , Ping Duan , Xian Zhang , Taiyang Yang , Qiuren Yang , Di Qiu , et al. The so-called "storm" means that this organization attempts to break the old barrier of traditional art, and sets off a raging tide of new art. -

Research and Education in the Contemporary Context of Art History from the Vision to the Art

3rd International Conference on Education, Management and Computing Technology (ICEMCT 2016) Research and Education in the Contemporary Context of Art History From the Vision to the Art Weikun Hao Hebei Institute of Fine Art, Shijiazhuang Hebei, 050700, China Keywords: Oil painting Techniques; Digital Image; Teaching Abstract. As is known to all, today's art education, its function has been far beyond the scope of training professional art talents. And from the perspective of the status quo of higher art education and skill training compared with history research, history research obviously in a weak position. From the Angle of art, art history is one of the important part of human art and culture, several conclusions show that for the study of art history and also learn the meaning of the obvious, such as improve the level of the fine arts disciplines, from the pure skills subject ascended to the status of the humanities; For today calls a "visual arts" or "visual culture" study, art history research is necessary; In carrying forward traditional culture today, the study of art history and learning will make human have more opportunity to participate in the fine arts with the human, and life, and emotion, contact with politics and history, for more understanding of cultural phenomenon. Introduction Plays a role in history of art history, art history research in the history of the grand is indispensable in the background, the history and culture is the concept of two inseparable. Obviously, for art history research to let a person produce both witness the massiness of history, and to experience the many things like the ramifications of fine arts. -

The Case for 1950S China-India History

Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ghosh, Arunabh. 2017. Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History. The Journal of Asian Studies 76, no. 3: 697-727. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41288160 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP DRAFT: DO NOT CITE OR CIRCULATE Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History Arunabh Ghosh ABSTRACT China-India history of the 1950s remains mired in concerns related to border demarcations and a teleological focus on the causes, course, and consequence of the war of 1962. The result is an overt emphasis on diplomatic and international history of a rather narrow form. In critiquing this narrowness, this paper offers an alternate chronology accompanied by two substantive case studies. Taken together, they demonstrate that an approach that takes seriously cultural, scientific and economic life leads to different sources and different historical arguments from an approach focused on political (and especially high political) life. Such a shift in emphasis, away from conflict, and onto moments of contact, comparison, cooperation, and competition, can contribute fresh perspectives not just on the histories of China and India, but also on histories of the Global South. Arunabh Ghosh ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of Modern Chinese History in the Department of History at Harvard University Vikram Seth first learned about the death of “Lita” in the Chinese city of Turfan on a sultry July day in 1981. -

Why China Cannot Adopt Capitalism

A CHINESE WEEKLY OF NEWS AND VIEWS Why China Cannot Adopt Capitalism Peace and Disarmament m Construction Site. Photo by Sun Chengyi Beijing HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WEEK VOL. 30, NO. 13 MARCH 30, 1987 CONTENTS NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 Macao to Return to China EVENT5AREN0S 5-9 'Sunday Engineers' Help Farmers p. 24 p. 20 Prosper Managers Receive In-Service Training Skvserapcrs Pose Problems lo Deng on the Recent Events Boning Self-Scrvice Stores: Can They • This article from the enlarged edition of Deng's Selected Survive? Works, deals with two major events — student unrest and the Energy Building in ihc Rural replacement of the Party General Secretary. In spite of these Areas events, there will be no change in the Party's line, principles and Weekly Chronicle (March 16-22) policies, says Deng (p. 33). INTERNATIONAL 10-13 Macao's Return Is Finalized Debt Problem: Mutual Compro-, • After eight months of negotiations, China and Portugal mise: the Only Way Out finally reached an agreement on the question of Macao, (Moup of 77: r.con(>niic Strategy another step towards the reunification of China (p. 4). In ihc Making Albania: Focus on Fconomic Developtnent China Spells Out Its Stand on Disarmament The United States: Weinberger s lli-Fated Visit • At a Beijing World Disarmament Campaign meeting sponsored by the UN, Chinese Vice-Foreign Minister Qian Qichen expounded China's nuclear policy and expressed the Worlfl Peace and Disarmament 14 government's concern about the spread of the arms race into NPC: Its Position and Roie 17 outer space. He also pointed out the relationship between The Election Process In Ttanjin 22 nuclear and conventional disarmament and urged the Why Capttafism is Impractical in superpowers to take the lead in all types of disarmament (p. -

The Storm Society Primary Sources in Translation from Shanghai Modern

The Storm Society Primary sources in translation from Shanghai Modern The Storm Society. Guan Liang. Mount Xiqiao. 1935. Oil on canvas; 50.5 x 57 cm. National Art Museum of China, Beijing. Guan Liang. Seated Nude. 1930. Oil on canvas; 60.5 x 45.5 cm. Private Collection. (Shanghai Modern, p. 183). Chen Baoyi. Scenery of West Shanghai. 1944. Oil on canvas; 44 x 52 cm. National Art Museum of China, Beijing. (Shanghai Modern, p. 184) Yan Wenliang. Red Sea. 1928. Oil on paperboard; 179 x 25.7 cm. National Art Museum of China, Beijing. (Shanghai Modern, p. 185). Ni Yide. Portrait of a Lady. 1950s. Watercolor on paper; 31.5 x 275 cm. China Academy of Art, Hangzhou. Situ Qiao. Lassoing Horses. 1944. Oil on canvas; 59 x 99 cm. National Art Museum of China, Beijing (Shanghai Modern, p. 188). Chen Qiucao. Sawing Wood. 1936. Oil on canvas; 67 x 67 cm. National Art Museum of China, Beijing. (Shanghai Modern, p. 189). Chen Qiucao. Flowers in the Trenches. 1940. Oil on canvas; 45.6 c 61 cm. National Art Museum of China, Beijing. (Shanghai Modern, p. 191) LEFT: Pang Xunqin. Winter. 1931. Oil on canvas; 47 x 36 cm. Private Collection. RIGHT: Qiu Ti, Shanghai View. 1947. Oil on canvasl 46 x 38 cm. Artist’s family. (Shanghai Modern, pp. 194-95). Chen Chengbo. Beach of the Putuo Mountain. 1930. Oil on canvas; 60 x 72 cm. (Shanghai Modern, p. 199). Liu Haisu (1896-1994). Girl Draped in Fox Fur. 1919. Oil on canvas; 60 cm x 45.5 cm. -

Beijing Essence Tour 【Tour Code:OBD4(Wed./Fri./Sun.) 、OBD5(Tues./Thur./Sun.)】

Beijing Essence Tour 【Tour Code:OBD4(Wed./Fri./Sun.) 、OBD5(Tues./Thur./Sun.)】 【OBD】Beijing Essence Tour Price List US $ per person Itinerary 1: Beijing 3N4D Tour Itinerary 2: Beijing 4N5D Tour Tour Fare Itinerary 1 3N4D Itinerary 2 4N5D O Level A Level B Level A Level B B OBD4A OBD4B OBD5A OBD5B D Valid Date WED/FRI WED/FRI/SUN TUE/THU TUE/THU/SUN 2011.3.1-2011.8.31 208 178 238 198 Beijing 2011.9.1-2011. 11.30 218 188 258 208 2011.12.1-2012. 2.29 188 168 218 188 Single Room Supp. 160 130 200 150 Tips 32 32 40 40 1) Price excludes tips. The tips are for tour guide, driver and bell boys in hotel. Children should pay as much as adults. 2) Specified items(self-financed): Remarks Beijing/Kung Fu Show (US $28/P); [Half price (no seat) for child below 1.0m; full price for child over 1.0m. Only one child without seat is allowed for two adults.] 3) Total Fare: tour fare + specified self-financed fee(US $28/P) The price is based on adults; the price for children can be found on Page 87 Detailed Start Dates (The Local Date in China) Date Every Tues. Every Wed. Every Thur. Every Fri. Every Sun. Month OBD5A/5B OBD4A/4B OBD5A/5B OBD4A/4B OBD4B/OBD5B 2011. 3. 01, 08, 15, 22, 29 02, 09, 16, 23, 30 03, 10, 17, 24, 31 04, 11, 18, 25 06, 13, 20, 27 2011. 4. 05, 12, 19, 26 06, 13, 20, 27 07, 14, 21, 28 01, 08, 15, 22, 29 03, 10, 17, 24 Tour Highlights Tour Code:OBD4A/B Wall】 of China. -

Effect of Modified Pomace on Copper Migration Via Riverbank Soil in Southwest China

Effect of modified pomace on copper migration via riverbank soil in southwest China Lingyuan Chen1,*, Touqeer Abbas2,*, Lin Yang1, Yao Xu1, Hongyan Deng1, Lei Hou3 and Wenbin Li1 1 College of Environmental Science and Engineering, China West Normal University, Nanchong, China 2 Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Agricultural Resources and Environment, Hangzhou, China 3 College of Resources & Environment, Tibet Agricultural and Animal Husbandry University, Nyingchi, China * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT To explore the effects of modified pomace on copper migration via the soil on the banks of the rivers in northern Sichuan and Chongqing, fruit pomace (P) and ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) modified P (EP) were evenly added (1% mass ratio) to the soil samples of Guanyuan, Nanbu, Jialing, and Hechuan from the Jialing River; Mianyang and Suining from the Fu River; and Guangan and Dazhou from the Qu River. The geochemical characteristics and migration rules of copper in different amended soils were simulated by column experiment. Results showed that the permeation time of copper in each soil column was categorized as EP-amended > P-amended > original soil, and the permeation time of amended soil samples at different locations was Jialing > Suining > Mianyang > Guangan > Dazhou > Nanbu > Guanyuan > Hechuan. Meanwhile, the average flow rate of copper in each soil column showed a reverse trend with the permeation time. Copper in exchangeable, carbonate, and iron–manganese oxide forms decreased with the increase of vertical depth in the soil column, among which the most evident decreases appeared in the carbonate-bonding form. The copper accumulation in different Submitted 8 October 2020 Accepted 1 July 2021 locations presented a trend of Jialing > Suining > Mianyang > Guangan > Dazhou > Published 27 July 2021 Nanbu > Guangyuan > Hechuan, and the copper content under the same soil showed Corresponding author EP-amended > P-amended > original soil. -

Biography of Ding Yanyong Mayching Kao Former Chair Professor, Department of Fine Arts the Chinese University of Hong Kong

Biography of Ding Yanyong Mayching Kao Former Chair Professor, Department of Fine Arts The Chinese University of Hong Kong 1902 Aged 1 Mr. Ding Yanyong was born on 15 April (the 8th day of the 3rd month in the 28th year of the reign of Guangxu) in Maopo Village, Xieji Town, Maoming County, Guangdong Province (present-day Gaozhou). Yanyong was his given name, to which style names Shudan and Jibo were added. His friends and students in Hong Kong addressed him as “Ding Gong”, meaning “the revered Mr. Ding”. Born in the zodiac year of the tiger (hu), he often used “Ding Hu” on his seals. His name in English is Ting Yin Yung. It is often romanized as Ting Yen-yung, but Ding Yanyong is in more common use nowadays. His oil paintings and sketches are signed “Y. Ting” and “Y. Y. Ting”. He came from a well-to-do family. His father, Ding Genci, was a cultivated man who enjoyed poetry and antiquities. At times he personally tutored his children in ancient poetry. Mr. Ding’s education began with a home tutor; he then attended a primary school in his home village, sponsored by his father. He was noted for his talents in painting and calligraphy as a child and his talents were much encouraged by his family and teachers. 1916 Aged 15 He attended Maoming County Middle School (present-day Gaozhou Secondary School). 1920 Aged 19 He graduated after four years of study. He went to Japan to study art under the auspices of the Guangdong provincial government. -

TENG%Yuning's

TENG%Yuning’s%Resume Personal)Information E"mail:([email protected] Mobile:(86"13810000598 Address(O):52(Yannan(Yuan,(Peking(University,(Beijing,(100871,(China. Tel(O):86"10"62767071 Education "( PhD(Candidate(in(Art(History(at(the(University(of(Hamburg,(Germany.(2017"( "( Master(of(Studies(in(Fine(Arts,(School(of(Arts,(Peking(University,(2005"2008() "( Bachelor( of( Arts( in( Film( and( TV( Program( Editing( and( Directing,( School( of( Arts,( Peking( University,( 2001"2005() Work)Experience ) Deputy)Director,)Centre(for(Visual(Studies(of(Peking(University,(2009"Now. Teng% works% at% Center%for%Visual%Studies%Peking%University%(CVS)% which% is% a% national% base% for% the% research% of% traditional%Chinese%art,%Chinese%contemporary%art%and%world%art%history.% As%the%deputy%director% there,%Teng ’s% main%academic%responsibility%is%managing%the%Chinese%Modern%Art%Archive%(CMAA),%which%collects%and%archives% Chinese%Contemporary%Art%dating%back%to%1986,%establishes%onIline% database,% hosts% academic% study% projects,% professional%exhibitions,%international%forums%and%seminars,%etc.% ( Executive)Editor;in;Chief,)Annual&of&Contemporary&Art&of&China,(2008"Now.(Before(that,(work)as( editor((11/2005"09/2006)(and(Director(of(Editing(Affairs,(09/2006"2008.( ( Vice)Secretary;General,(Wu(Zuoren(International(Foundation(of(Fine(Arts(WIFA),(2013"Now.( Major)Member)of)CIHA;China)Secretariat,)2012"Now,)and)Junior)Chair)of)the)Session)11,) “Landscape)and)spectacle”)of)CIHA2016,)2016.)) ) AICA)Member,)Member(of(the(International(Association(of(Art(Critics((AICA),(2018"Now) -

Modern Art 109

Modern Art 109 Fall 2018 Tu/Th 1:30-2:45 pm Kadema Hall 145 Professor: Elaine O'Brien, Ph.D. Office: Kadema Hall 190 Office Hours: T 6-7 PM, W 3-5 PM (and by appointment) [email protected] http://www.csus.edu/indiv/o/obriene/ https://twitter.com/eoarthistory Course description: This is a survey of avant-garde modern art from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. The first half of the course will focus on the art of Western Europe and the United States. In the second half, we consider case studies of modern art in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Taking a world perspective on Modern art, which was the first truly global visual language, we will see how the aesthetic of newness, originality, anti-academicism, and radical formal invention characteristic of avant-garde modernism was rooted in the universal societal transformation that was modernity: the rise to power of urban middle classes, secularism, positivism, faith in “progress,” individualism, and capitalism. Modern art was the product of the forces of modernization – industrialization, urbanization, colonialism – that transformed the entire world during the era we study. After defining “Modern” art and “Modernism,” the course begins with the Post Impressionism of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin and proceeds through the modern movements of Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, Constructivism, Dada, and Surrealism: movements that fundamentally reinvented the vocabulary of visual art. The first half of the course concludes with American Abstract Expressionism in the World War II decade that saw the end of the Age of Europe. -

Quest for the Source of the Irrawaddy in the Steps of Bailey and Kingdon-Ward

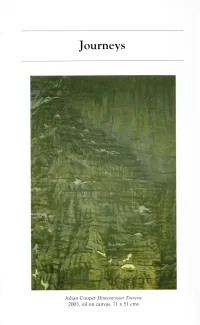

Journeys Julian Cooper Hinrerstoisser Traverse 2003, oil on canvas, 71 x 51 cms TAMOTSU NAKAMURA Quest for the Source of the Irrawaddy In the Steps of Bailey and Kingdon-Ward If you travel north-westwards from Yakalo (Yangjing), you meet with snow peaks at every turn, growing ever more lofty. There is a perfect botanist's paradise in that mountainous and little-known country beyond the source of the Irrawaddy. Frank Kingdon-Ward, China to Khamti Long he year 1999 held bitter experiences for us, elderly explorers searching T for the source of the Irrawaddy. We had long hoped to trace the footsteps of FM Bailey in 1911 and Frank Kingdon-Ward in 1911-13 across the gorge country from China to Assam in India. Our plan was to approach the headwaters of the Irrawaddy from forbidden ZayuI County in south east Tibet, adjacent to the border with the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh and northern Myanmar, and then traverse the three river gorges of the upper Salween, Mekong and Yangtze. Our main objective was a quest for mountains at the headwaters of the Irrawaddy and a search for unknown glaciated snow peaks over 6000m in the heart of the Baxoila Ling range. We departed from Deqen in Yunnan province at the end of May. Before arriving at Zayul, however, we discovered that our travel agent had not obtained a special permit allowing us to travel through an area strictly prohibited to foreigners. Our illegal entry caused serious trouble. We were arrested near Lhasa by the Public Security Bureau and a heavy penalty was imposed by the Chinese authorities. -

“China” on Display for European Audiences? the Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art–China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993)

66 “China” on Display for European Audiences? “China” on Display for European Audiences? The Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art–China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993) Franziska Koch, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Contemporary Chinese Art–Phenomenon and Discursive Category Mediated by Exhibitions Exhibitions have always been at the heart of the modern art world and its latest developments. They are contested sites where the joint forces of art objects, their social agents, and institutional spaces intersect temporarily and provide a visual arrangement for specific audiences, whose interpretations themselves feed back into the discourse on art. Viewed from this perspective, contemporary Chinese art–as a phenomenon and as a discursive category that refer to specific dimensions of artistic production in post-1979 China– was mediated through various exhibitions that took place in the People’s Republic of China (hereafter, People’s Republic). In 1989, art from the People’s Republic also began to appear in European and North American exhibitions significantly expanding Western knowledge of this artistic production. Since then, national and international exhibitions have multiplied, while simultaneously becoming increasingly entangled: the sheer number of artworks that circulate between Chinese urban art scenes and Western art metropolises has risen steeply, as have the often overlapping circles of contemporary artists, art critics, art historians, gallery owners, and collectors who successfully engage across both sides of the field. To a certain degree these agents govern exhibition-making and act as important mediators or “cultural brokers”1 globalizing the discursive category of contemporary 1 For a recent study that explores the notion of the “cultural broker” from a transcultural perspective see Rudolf G.