Bharathidasan University Central Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

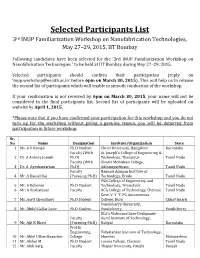

Selected Participants List 3Rd INUP Familiarization Workshop on Nanofabrication Technologies, May 27–29, 2015, IIT Bombay

Selected Participants List 3rd INUP Familiarization Workshop on Nanofabrication Technologies, May 27–29, 2015, IIT Bombay Following candidates have been selected for the '3rd INUP Familiarization Workshop on Nanofabrication Technologies ' to be held at IIT Bombay during May 27–29, 2015. Selected participants should confirm their participation (reply on ‘[email protected]’ before 6pm on March 30, 2015). This will help us to release the second list of participants which will enable in smooth conduction of the workshop. If your confirmation is not received by 6pm on March 30, 2015, your name will not be considered in the final participants list. Second list of participants will be uploaded on website by April 1, 2015. *Please note that if you have confirmed your participation for this workshop and you do not turn up for the workshop without giving a genuine reason, you will be debarred from participation in future workshop. Sr. No Name Designation Institute/Organization State 1 Ms. A V Ramya Ph.D Student Christ University, Bangalore Karnataka Faculty (With St. Joseph's College of Engineering & 2 Dr. A Antony Joseph Ph.D) Technology, Thanjavur Tamil Nadu Faculty (With Khadir Mohideen College, 3 Dr. A Ayeshamariam Ph.D) Adirampattinam Tamil Nadu Faculty Bannari Amman Institute of 4 Mr. A Daniel Raj (Pursuing Ph.D) Technology, Erode Tamil Nadu PSN College of Engineering and 5 Mr. A Kuberan Ph.D Student Technology, Tirunelveli Tamil Nadu 6 Mr. A Venkatesan Faculty KCG College of Technology, Chennai Tamil Nadu Govt. V. Y. T. PG Autonomous 7 Ms. Aarti Choudhary Ph.D Student College, Durg Chhattisgarh Pondicherry University, 8 Mr. -

UGC–Human Resource Development Centre BHARATHIDASAN

UGC–Human Resource Development Centre BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY (Re-accredited by NAAC with ‘A’ Grade) Khajamalai Campus, Trichy - 620 023, TN, India +91 431 2331062 [email protected] www.ugchrdcbdu.org UGC-Sponsored Refresher Course in English Language & Literature Provisional Selection List The following applicants are provisionally selected for the UGC-Sponsored Refresher Course in English Language & Literature to be conducted from 19.06.2018 (Tuesday) to 09.07.2018 (Monday), subject to the following conditions, in addition to the usual rules and regulations of the UGC - HRDC: The HRDC does not pay TA / DA to the participants. Each selected applicant has to confirm his / her participation through e-mail ([email protected]) or SMS (+918973423347) with the name, department and institution before 5.00.p.m. 08.06.2018. Failure to send confirmation, as specified above will be viewed as the respective applicant’s inability to participate and the vacancy thus created will be filled with an applicant from the Waiting List. Each applicant who confirms his/her participation will get the Selection Order through e-mail. Outstation participants who have submitted the Registration Forms for Guest House accommodation will receive a separate e-mail regarding the same after the confirmation. Director i/c UGC-Sponsored Refresher Course in English Language & Literature Provisional Selection List Sl. Name, Designation & Institution No. 1) Dr. J. John Love Joy, Assistant Professor of English, St. Joseph's College(Auto), Tiruchirappalli 2) Dr. P.Suganthi, Assistant Professor of English, Poompuhar College, Melaiyur 3) Jayapaul V.L., Assistant Professor of English, St. Joseph's College(Auto), Tiruchirappalli 4) Dr. -

Download Thesis

STUDIES ON PATHOGENIC BACTERIA AND FUNGUS OF SHRIMP, PENAEUS MONODON CULTURED IN SEMI- INTENSIVE PONDS IN THE COASTAL AREA OF THANJAVUR DISTRICT, TAMIL NADU, INDIA THESIS SUBMITTED TO BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY, TIRUCHIRAPPALLI FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ZOOLOGY By R. RAVICHELVAN Under the guidance of Dr. A. AMSATH, Associate Professor POST-GRADUATE AND RESEARCH DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY KHADIR MOHIDEEN COLLEGE ADIRAMPATTINAM – 614 701 JUNE 2011 Dr. A. AMSATH, M. Sc., M. Phil., Ph. D., Associate Professor and Research Advisor P.G. and Research Department of Zoology, Khadir Mohideen College, Adirampattinam – 614 701. Tamil Nadu, India Date:………..…………… CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “STUDIES ON PATHOGENIC BACTERIA AND FUNGUS OF SHRIMP, PENAEUS MONODON CULTURED IN SEMI-INTENSIVE PONDS IN THE COASTAL AREA OF THANJAVUR DISTRICT, TAMIL NADU, INDIA” submitted to Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli, for the aaward of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ZOOLOGY, embodies the result of the bonafide research work carried out during the year 2008-2011 by Mr. R. RAVICHELVAN, under my guidance and supervision in the P.G. and Research Department of Zoology, Khadir Mohideen College, Adirampattinam, Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India. I further certify that no part of this thesis has been submitted anywhere else for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship or other similar titles to any candidate. DECLARATION I do hereby declare that this thesis work has been originally carried out during the year 2008-2011 by me under the guidance and supervision of Dr. A. AMSATH, M.Sc., M.Phil., Ph.D., Research Advisor and Associate Professor, P.G. -

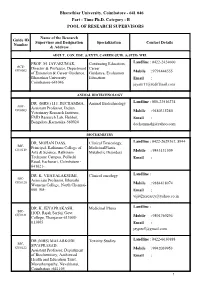

Bharathiar University, Coimbatore - 641 046 Part - Time Ph.D

Bharathiar University, Coimbatore - 641 046 Part - Time Ph.D. Category - B POOL OF RESEARCH SUPERVISORS Name of the Research Guide ID Supervisor and Designation Specialization Contact Details Number & Address ADULT . CON. EDU. & EXTN. CAREER GUID. & STUD. WEL PROF. M. JAYAKUMAR, Continuing Education, Landline : 0422-2424600 ACE- Director & Professor, Department Career GU0002 of Extension & Career Guidance, Guidance, Evaluation Mobile : 9791444555 Bharathiar University Education Email : Coimbatore-641046 [email protected] ANIMAL BIOTECHNOLOGY DR. (MRS.) H.J. DECHAMMA, Animal Biotechnology Landline : 080-23516274 ABT- Assistant Professor, Indian GU0003 Veterinary Research Institute, Mobile : 9480315280 FMD Research Lab, Hebbal, Email : Bangalore,Karnataka-560024 [email protected] BIOCHEMISTRY DR. MOHAN DASS, Clinical Toxicology, Landline : 0422-2629367, 8944 BIC- Principal, Rathinam College of MedicinalPlants, GU0119 Arts & Science, Rathinam Metabolic Disorders Mobile : 9843131509 Techzone Campus, Pollachi Email : Road, Eachanari, Coimbatore - 641021- DR. K. VIJAYALAKSHMI, Clinical oncology Landline : BIC- Associate Professor, Bharathi GU0120 Womens College, North Chennai- Mobile : 9884418074 600 108- Email : [email protected] DR. K. JEYAPRAKASH, Medicinal Plants Landline : BIC- HOD, Rajah Serfoji Govt. GU0121 College, Thanjavur-613005- Mobile : 9894769294 613005 Email : [email protected] DR.(MRS) MALARKODI Toxicity Studies Landline : 0422-6630888 BIC- SIVAPRASAD, GU0122 Assistant Professor, Department Mobile : 9942039953 of Biochemistry, Aashirwad Email : Health and Education Trust, Mavuthampathy, Navakkarai, Coimbatore -641105 1 DR. P. SUMATHI, Clinical Bio-Chemistry Landline : 044-27454863 BIC- Assistant Professor, Govt. GU0123 College for Women, Krishnagiri- Mobile : 9444151677 635001 Email : DR. M. JEYARAJ, Plant Bio-Chemistry Landline : BIC- Lecturer, Dept. of Biochemistry, GU0124 Government of Arts College, Mobile : 9787059193 Paramakudi , Ramnad Dt., Email : Tamilnadu-623707 [email protected] [email protected] DR. -

IT Is Happening at SASTRA

ITIHAS IT Is Happening At SASTRA Newsletter from SASTRA DEEMED UNIVERSITY Vol 19 IV Quarter 2019 MESSAGE FROM THE VICE-CHANCELLOR SASTRA-RAMANUJAN AWARD 2019 SASTRA has made an indelible mark in The SASTRA Ramanujan Award for 2019 was the international scientific community by awarded to mathematician Dr. Adam Harper, Assistant earning the recognition of the Royal Society Professor, University of Warwick, England. The prize at England for its SASTRA-Ramanujan carries a citation and an award of $10,000 and is Award, which it confers annually on young researchers in Mathematics. In its December conferred annually on mathematicians from across the 2019 Special Issue of the ‘Philosophical world, who are less than 32 years of age, working in Transactions’ to commemorate the an area influenced by the genius Srinivasa Ramanujan. Centenary of Ramanujan’s election as FRS, the Royal Society The SASTRA-Ramanujan Award has gained global has commended SASTRA’s effort by publishing a paper titled repute ever since it was instituted in 2005 and today “Ramanujan’s Legacy: The Work of SASTRA Prize Winners”. It is easily amongst the top five awards of this type for is also noteworthy that four recipients of SASTRA-Ramanujan mathematics. Dr.S. Vaidhyasubramaniam, the Vice- Award have gone on to win the Fields Medal. Chancellor of SASTRA University, in his welcome note The 2019 SASTRA-Ramanujan Award was presented to Adam mentioned that many previous winners of SASTRA- Harper of the University of Warwick for his outstanding contributions to probabilistic number theory. Ken Ono, Ramanujan Award, including Manjul Bhargava and the Vice President of the American Mathematical Society, Akshay Venkatesh, have gone on to win the Fields recalled that Harper was the Ph.D student of Prof.Ben Green Medal subsequently. -

List of Reviewers (As Per the Published Articles) Year: 2017

List of Reviewers (as per the published articles) Year: 2017 Physical Science International Journal ISSN: 2348-0130 Past name: Physical Review & Research International ISSN: 2231-1815 (old) 2017 - Volume 13 [Issue 1] DOI : 10.9734/PSIJ/2017/30833 (1) Francisco Frutos-Alfaro, School of Physics and Space Research Center, University of Costa Rica, Costa Ricaa. (2) Sanjay S. Sastry, C F Cosmological Center, USA. (3) Y. Harold Robinson, Anna University, India. (4) Piero Chiarelli, University of Pisa, Italy. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17134 DOI : 10.9734/PSIJ/2017/25852 (1) Ucuk Darusalam, Nasional University, Indonesia. (2) Abubakar Yakubu, University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17150 DOI : 10.9734/PSIJ/2017/30140 (1) Maxim Eingorn, North Carolina Central University, Durham, North Carolina, U.S.A. (2) Roger Ellman, The-Origin Foundation, Inc., Santa Rosa, CA, USA. (3) C.G. Sim, Chungbuk Health & Science University, South korea. (4) Luis Acedo Rodríguez, Instituto Universitario de Matemática Multidisciplinar, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17237 DOI : 10.9734/PSIJ/2017/27869 (1) Animasaun L. Isaac, Federal University of Technology, Nigeria. (2) B. J. Gireesha, Kuvempu University, India. (3) S. R. Mishra, SOA University, India. (4) Anonymous, Majma’ah University, Saudi Arabia. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17239 DOI : 10.9734/PSIJ/2017/30061 (1) Leinig Antonio Perazolli, Chemical Institute of Araraquara, Brasil. (2) Fathia Mamdouh, National Research Center, Egypt. (3) Ambran Hartono, Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic State University Jakarta, Indonesia. -

Higher Studies Details

Institute Name FATIMA COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) India Rankings 2017 ID IR17-COLL-1-15202 Discipline SINGLE Parameter Students opting for higher studies Graduating year of the Name of the Number of Students 3A.GPHE S.No. Year of Admission Student University/Institutions Admitted 1. M K University, Madurai 62 2. M T W University, Kodaikkanal 5 3. Alagappa University, Karaikudi 4 4. M S Univerisy, Tirunelveli 1 5. Karunya University, Coimbatore 2 6. Gandhigram Rural Institute, 3 Gandhigram 7. Thiagarajar College of Engineering, 3 Madurai 8. PSNA College of Engineering and 6 Technology, Dindigul 9. Fatima College, Madurai 219 10. Ethiraj College, Chennai 1 11. Stella Maris College, Chennai 1 12. SRM College, Chennai 1 13. Lady Doak College, Madurai 2 14. Thiagarajar College, Madurai 13 1 2015-16 2016 15. Thiagarajar College of Preceptors, 1 Madurai 16. Thiagarajar School of 1 Management, Madurai 17. St. Charles College of Education 1 18. Aurobindo Mira College of 3 Education, Madurai 19. Mangaiyarkarasi College, Madurai 15 20. St. Justin's College of Education 4 21. M G R College, Krishnagiri 1 22. St. Joseph's College, Trichy 6 1 2015-16 2016 23. Yadava College, Madurai 2 24. The American College, Madurai 10 25. Madura College, Madurai 8 26. Sri Ram Institute of Management 1 27. J A College, Periyakulam 1 28. PSGR Krishnammal College, 4 Coimbatore 29. Sri Meenakshi Govt. College for 1 Women, Madurai 30. Madurai Institute of Management, 1 Madurai 31. Fatima Michael College, Madurai 1 32. C S I Arts College, Madurai 2 1 2015-16 2016 33. S N College, Madurai 1 34. -

Dr. M.Parveen Guest Faculty Contact Address

Dr. M.Parveen Guest Faculty Contact Address : Bharathidasan School of Management Bharathidasan University Tiruchirappalli – 620 024 Tamil Nadu, INDIA Date of Birth : 20-11-1982 Contact Phone (Mobile) : +91 9894514488 Contact e-mail(s) : [email protected] Academic Qualifications: M.A./M.Sc./M.Phil./Ph.D./ Ph.D in Management (Financial Management) Bharathidasan University, India Khadir Mohideen College January 2012-January 2015 M.Phil (FINANCE) Bharathidasan University, India Jamal Mohamed College June 2007-May2009 MBA (FINANCE) Bharathidasan University, India Jamal Mohamed College June 2003-May 2005 MHRM (HUMAN RESOURCES MANAGEMENT) Bharathidasan University, Indai Jamal Mohamed College June 2009-May 2011 B.Com Bharathidasan University, India Jamal Mohamed College June 2000-May 2003 Teaching Experience: 10 Years 04 Months Serving as Guest Faculty in Bharathidasan School of Management, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli – 24, from September 2018 – till date. Served as Assistant Professor in Jamal Institute of Management, Jamal Mohamed College, Tiruchirappalli – 20, from August 2006 to November 2016 Research Experience: 10 Years MBA projects have guided for students of Jamal Institute of Management, Bharathidasan University, Anna University and Annamalai University. Research Scholar from 2011-2015 Additional Responsibilities 1. Admission Committee/ Association Activities, 2. Academic club Activities (Finance Club), 3. Work load / Time table preparation 4. Semester Action Plan / Teaching Plan/ Cycle test Assessment. 5. Identify and organize field trips to enhance curriculum, Areas of Research Financial Management Human Resource Management Research Supervision / Guidance Program of Study Completed Ongoing Research Ph.D. - - M.Phil. - - Project PG 98 - UG / Others - - Publications International National Others Journals Conferences Journals Conferences Books / Chapters / Monographs / Manuals 05 00 02 14 - Distinctive Achievements / Awards 1. -

0461 – 321655 To

TUTICORIN DISTRICT COLLEGE NAMES TO The principal APC Mahalakshmi College for Women Tuticorin - 628 016. Ph: 0461 – 321655 TO The principal Bishop Caldwall College Tuticorin TO The principal Dr.Sivanthi Aditanar College of Engineering, Tiruchendur, Tuticorin District, Pin Code - 628215 242482, 245854 TO The principal G.V.N.College Kovilpatti - 627 702. Ph: 04632 - 20389 04632 – 20389 TO The principal G.Venkatasamy Naidu College(Self Financing Courses), Kovilpatti - 628501, Thoothukodi Dt, Tamilna +91- 4632 225389 TO The principal Govindammal Aditanar College Tiruchendur - 628 215. +914639242184 TO The Head Of The Department Infant Jesus College of Engineering, Kamarajar Nagar, Thoothukudi Highway (NH 7/A), Ellanayakan 04630 - 262650, 2944 TO The principal Kamaraj College Thiruchendur Road, Tuticorin 628 003 Ph: 0461 - 321988 0461 - 321988 TO The principal M.S.University Constituent College for Women, Sathankulam, Tuticorin District TO The principal S.S.Duraisamy Nadar Mariammal College Pasuvanthanai Road , Kovilpatti - 628501, Tamilnadu, TO The principal Sri K.G.S.Arts College Padmanabamangalam, Srivaikuntam - 628 619. Tuticorin dist Ph: 04630 - 8224 04630 – 8224 TO The principal St Marys College North Beach Road, Tuticorin 628 001 Ph: 0461 - 321606 0461 – 321606 TO The principal VOC College Tuticorin - 628 008. Ph: 0461 - 320492 0461 – 320492 DINDIGUL DISTRICT COLLEGE NAMES TO The Head Of The Department Department of management studies PSNA College Of Engineering & Technology KothandaramanNagar, DindigulDistrict, Pin Code - 6246 2554032, 2554401 TO The principal G.T.N arts college Karur Road Dindigul Pin Code 624 005 0451 - 242 1900 TO The principal M.V. Muthiah Govt. Arts College for Women Thandicombu Road Dindigul Pin Code 624 008 0451 - 242 2011 TO The principal N.P.R. -

DR. M. CHANDRAN M.Sc., M.Phil., B.Ed., Ph.D., Associate Professor

DR. M. CHANDRAN M.Sc., M.Phil., B.Ed., Ph.D., Associate Professor PERSONAL DETAILS Designation : Associate Professor Father’s Name : Muthiah Department Address: Department of Zoology. Thiruvalluvar University, Serkadu, Vellore-632115 Tamil Nadu, India. Contact :Office: 0416- 2274900 Mobile:91-7305886169 E-mail :[email protected] Residential Address : 114, Kamarajar Street, Bone Mill Stop Katpadi, Vellore-632 007 Tamil Nadu, India. ➢ EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION S. Examinations Subject Year of Division/ Name of the Board / NO Passing Class/ University Grade 1. B.Sc., Zoology Madurai Kamaraj 1988 II University 2. M.Sc., Zoology Madurai Kamaraj 1992 I University 3. M. Phil. Energy Madurai Kamaraj 1991 I University 4. B.Ed. Biological Madurai Kamaraj 1994 II Science University 5. Ph. D./ D. Zoology Dept. of Zoology 1999 Highly Phil. Annamalai University Commanded ➢ EXPERIENCE DETAILS S. Positions Name of the Institutions Duration Years of NO held Experience From To 1. Lecturer ANJA College, 19.06.2000 27.03.2002 2 years 2. Lecturer Alagappa Govt. College, 01.07.2004 31.03.2005 1 year Karaikudi. 3. Lecturer Raja Serfoji Govt. College. 15.07.2005 01.02.2007 2 years Thanjavur. 4. Asst. Thiagarajar College, Madurai- 21.02.2007 2013 7 years Professor 09 5. Associate Thiruvalluvar University, 21.02.2013 Till date - Professor Serkkadu, Vellore-115. Teaching Experience : 19 years Research Experience : 24 years Research Area : Environmental toxicology, Malacology, Ethanopharmacology and Nano Science Mphil. Thesis Title : Influence of various salinity of the ambient medium on the blood serum osmolality of Cyprinus carpio (l) Ph.D. Thesis Title :Studies on the effect of optic tentacle and medio dorsal body exract on metabolism and reproduction in Laevicaulis alte (Ferrusac) (Mollusca: Gastropoda). -

620 024 List of Senate Members

BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY Tiruchirappalli - 620 024 List of Senate Members Class – 1 – Ex-officio Members 1. Shri. R.N. Ravi Hon’ble Governor of Tamil Nadu & Chancellor of Bharathidasan University Raj Bhavan Chennai – 600 022 2. Thiru. K.Ponmudi Hon’ble Minister for Higher Education & Pro-Chancellor of Bharathidasan University Secretariat, Fort St. George Chennai – 600 009 3. Dr. M. Selvam Vice-Chancellor Bharathidasan University Tiruchirappalli- 620 024 4. Dr. C. Pooranachandran Director of Collegiate Education Directorate of Collegiate Education 9TH Floor, E.V.K. Sampath Maaligai College Road, Nungambakkam Chennai – 600 006 5. Dr. V.C. Rameswaramurugan Director of School Education College Road ( DPI Compound ) Chennai – 600 006 6. Tmt. G. Laxmi Priya , I.A.S. Director of Technical Education Directorate of Technical Education Sardar Patel Road, Guindy Chennai – 600 025 7. Prof. (Dr.) C. Chockalingam Director of Legal Studies Purasaiwalkam High Road Kilpauk Chennai – 600 010 1 8. Dr. R. Narayanababu Director of Medical Education i/c Directorate of Medical Education # 162, Periyar EVR High Road Kilpauk Chennai – 600 010 HEADS OF UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS OF STUDY AND RESEARCH 9. Dr. C. Isaac Jebastine Professor and Head Department of English Bharathidasan University Tiruchirappalli – 620 024 10. Dr. J.A. Arul Chellakumar Professor and Head Department of Economics Bharathidasan University Tiruchirappalli – 620 024 11. Dr. A. Tamilselvan Professor and Head Department of Mathematics Bharathidasan University Tiruchirappalli – 620 024 12. Dr. T. Jai Sankar Assistant Professor and Head Department of Statistics Bharathidasan University Khajamalai Campus Tiruchirappalli – 620 023 13. Dr. L.C. Nehru Assistant Professor and Head Department of Medical Physics Bharathidasan University Tiruchirappalli – 620 024 14. -

4. Annual Quality Assurance Report

Annual Quality Assurance Report (Revised Format) (AQAR 2018 - 19) Submitted to NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL Bengaluru-560 072 By Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) SENGAMALA THAYAAR EDUCATIONAL TRUST WOMEN’S COLLEGE (Affiliated to Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli) (NAAC accredited ‘A’ Grade with CGPA 3.45 / 4.00) (An ISO 9001:2015 Certified Institution) SUNDARAKKOTTAI, MANNARGUDI – 614 016 TIRUVARUR DISTRICT, TAMIL NADU. AQAR 2018-2019 – NAAC – Revised Format The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC Part – A Data of the Institution 1. Name of the Institution : SENGAMALA THAYAAR EDUCATIONALTRUST WOMEN’S COLLEGE Name of the Head of the Institution: Dr.S.Amudha Designation : Principal Does the institution function : Yes from own campus Phone No. / Alternate Phone No. : 04367 – 255423 Mobile No. : 9443703331 Registered e-mail : [email protected] Alternate e-mail : [email protected] Address : Main Road, Sundarakkottai Village, Mannargudi, Thiruvarur District. City/Town : Mannargudi State/UT : TamilNadu Pin Code : 614 016 2. Institution Status Affiliated / Constituent : Affiliated Type of Institution : Co-education/Men/Women : Women Location : Rural/Semi-urban/Urban: Rural S.T.E.T. Women’s College, Sundarakkottai, Mannargudi, TN, India Page 1 AQAR 2018-2019 – NAAC – Revised Format Financial Status : Private Name of the IQAC Co-ordinator : Dr.R.Saravanamuthu Phone No./Alternate Phone No. : 04367 - 255423 Mobile No. : 9842618181 Registered e-mail address : [email protected] Alternate e-mail address : [email protected] 3. Website address : www.stet.edu.in Web-link of the AQAR http://stet.edu.in/AQAR/AQAR2018-19.pdf 4. Whether Academic Calendar prepared during the year? : Yes Web link : http://stet.edu.in/AQAR/CALENDAR2018-19.pdf 5.