Justification for a Standardised Zoological Nomenclature: the Fascinating World of Animal Common Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

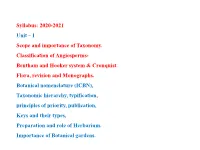

I Scope and Importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker System & Cronquist

Syllabus: 2020-2021 Unit – I Scope and importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker system & Cronquist. Flora, revision and Monographs. Botanical nomenclature (ICBN), Taxonomic hierarchy, typification, principles of priority, publication, Keys and their types, Preparation and role of Herbarium. Importance of Botanical gardens. PLANT KINGDOM Amongst plants nearly 15,000 species belong to Mosses and Liverworts, 12,700 Ferns and their allies, 1,079 Gymnosperms and 295,383 Angiosperms (belonging to about 485 families and 13,372 genera), considered to be the most recent and vigorous group of plants that have occurred on earth. Angiosperms occupy the majority of the terrestrial space on earth, and are the major components of the world‘s vegetation. Brazil (First) and Colombia (second), both located in the tropics considered to be countries with the most diverse angiosperms floras China (Third) even though the main part of her land is not located in the tropics, the number of angiosperms still occupies the third place in the world. In INDIA there are about 18042 species of flowering plants approximately 320 families, 40 genera and 30,000 species. IUCN Red list Categories: EX –Extinct; EW- Extinct in the Wild-Threatened; CR -Critically Endangered; VU- Vulnerable Angiosperm (Flowering Plants) SPECIES RICHNESS AROUND THE WORLD PLANT CLASSIFICATION Historia Plantarum - the earliest surviving treatise on plants in which Theophrastus listed the names of over 500 plant species. Artificial system of Classification Theophrastus attempted common groupings of folklore combined with growth form such as ( Tree Shrub; Undershrub); or Herb. Or (Annual and Biennials plants) or (Cyme and Raceme inflorescences) or (Archichlamydeae and Meta chlamydeae) or (Upper or Lower ovarian ). -

Review and Updated Checklist of Freshwater Fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, Distribution and Conservation Status

Iran. J. Ichthyol. (March 2017), 4(Suppl. 1): 1–114 Received: October 18, 2016 © 2017 Iranian Society of Ichthyology Accepted: February 30, 2017 P-ISSN: 2383-1561; E-ISSN: 2383-0964 doi: 10.7508/iji.2017 http://www.ijichthyol.org Review and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, distribution and conservation status Hamid Reza ESMAEILI1*, Hamidreza MEHRABAN1, Keivan ABBASI2, Yazdan KEIVANY3, Brian W. COAD4 1Ichthyology and Molecular Systematics Research Laboratory, Zoology Section, Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran 2Inland Waters Aquaculture Research Center. Iranian Fisheries Sciences Research Institute. Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization, Bandar Anzali, Iran 3Department of Natural Resources (Fisheries Division), Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan 84156-83111, Iran 4Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 6P4 Canada *Email: [email protected] Abstract: This checklist aims to reviews and summarize the results of the systematic and zoogeographical research on the Iranian inland ichthyofauna that has been carried out for more than 200 years. Since the work of J.J. Heckel (1846-1849), the number of valid species has increased significantly and the systematic status of many of the species has changed, and reorganization and updating of the published information has become essential. Here we take the opportunity to provide a new and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran based on literature and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history and new fish collections. This article lists 288 species in 107 genera, 28 families, 22 orders and 3 classes reported from different Iranian basins. However, presence of 23 reported species in Iranian waters needs confirmation by specimens. -

International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature INTERNATIONAL CODE OF ZOOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE Fourth Edition adopted by the International Union of Biological Sciences The provisions of this Code supersede those of the previous editions with effect from 1 January 2000 ISBN 0 85301 006 4 The author of this Code is the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature Editorial Committee W.D.L. Ride, Chairman H.G. Cogger C. Dupuis O. Kraus A. Minelli F. C. Thompson P.K. Tubbs All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise), without the prior written consent of the publisher and copyright holder. Published by The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 c/o The Natural History Museum - Cromwell Road - London SW7 5BD - UK © International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 Explanatory Note This Code has been adopted by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature and has been ratified by the Executive Committee of the International Union of Biological Sciences (IUBS) acting on behalf of the Union's General Assembly. The Commission may authorize official texts in any language, and all such texts are equivalent in force and meaning (Article 87). The Code proper comprises the Preamble, 90 Articles (grouped in 18 Chapters) and the Glossary. Each Article consists of one or more mandatory provisions, which are sometimes accompanied by Recommendations and/or illustrative Examples. In interpreting the Code the meaning of a word or expression is to be taken as that given in the Glossary (see Article 89). -

Arachnida: Araneae) Para México Y Listado Actualizado De La Araneofauna Del Estado De Coahuila

ISSN 0065-1737 (NUEVA SERIE) 34(1) 2018 e ISSN 2448-8445 NUEVOS REGISTROS DE ARAÑAS (ARACHNIDA: ARANEAE) PARA MÉXICO Y LISTADO ACTUALIZADO DE LA ARANEOFAUNA DEL ESTADO DE COAHUILA NEW RECORDS OF SPIDERS (ARACHNIDA: ARANEAE) FROM MEXICO AND LISTING OF SPIDERS FROM COAHUILA STATE Marco Antonio DESALES-LARA,1,2 María Luisa JIMÉNEZ3,* y Pablo CORCUERA2 1 Doctorado en Ciencias Biológicas y de la Salud, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa (UAM-I). Av. San Rafael Atlixco 186. Col. Vicentina Iztapalapa, C.P. 09340, Cd de México, México <[email protected]> 2 Laboratorio de Ecología Animal, Departamento de Biología, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa (UAM-I). Av. San Rafael Atlixco 186. Col. Vicentina Iztapalapa, C.P. 09340, Cd de México, México. <pcmr@ xanum.uam.mx> 3 Laboratorio de Aracnología y Entomología, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste. Instituto Politécnico Nacional 195, Col. Playa Palo de Santa Rita Sur, C.P. 23096 La Paz, Baja California Sur, México. <[email protected]> *Autor para correspondencia: <[email protected]> Recibido: 27/06/2017; aceptado: 01/12/2017 Editor responsable: Guillermo Ibarra Núñez Desales-Lara, M. A., Jiménez, M. L. y Corcuera, P. (2018) Nuevos Desales-Lara, M. A., Jiménez, M. L., & Corcuera, P. (2018) New registros de arañas (Arachnida: Araneae) para México y listado records of spiders (Arachnida: Araneae) from Mexico and listing actualizado de la araneofauna del estado de Coahuila. Acta Zooló- of spiders from Coahuila state. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n.s), gica Mexicana (n.s), 34(1), 50-63. 34(1), 50-63. RESUMEN. Se dan a conocer cuatro nuevos registros de especies ABSTRACT. -

Tour Report 1 – 8 January 2016

The Gambia - In Style! Naturetrek Tour Report 1 – 8 January 2016 White-throated Bee-eaters Violet Turaco by Kim Taylor African Wattled Lapwing Blue-bellied Roller Report compiled by Marcus John Images courtesy of Kim Taylor & Marcus John Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk The Gambia - In Style! Tour Report Tour Participants: Marcus John (leaders) with six Naturetrek clients Summary The Gambia is an ideal destination for a relaxed holiday and offers a great introduction to the diverse and colourful birdlife of Africa. We spent the week at the stunning Mandina Lodges, a unique place that lies on a secluded mangrove-lined tributary of the mighty River Gambia. The lodges are situated next to the creek and within the Makasuto Forest, which comprises over a thousand acres of pristine, protected forest. Daily walks took us out through the woodland and into the rice fields and farmland beyond, where a great range of birds and butterflies can be found. It was sometimes hard to know where to look as parrots, turacos, rollers and bee-eaters all vied for our attention! Guinea Baboons are resident in the forest and were very approachable; Green Vervet Monkeys were seen nearly every day and we also found a group of long-limbed Patas Monkeys, the fastest primates in the world! Boat trips along the creek revealed a diverse selection of waders, kingfishers and other waterbirds; fourteen species of raptor were also seen during the week. -

29Th 2019-Uganda

AVIAN SAFARIS 23 DAY UGANDA BIRDING AND NATURE TOUR ITINERARY Date: July 7 July 29, 2019 Tour Leader: Crammy Wanyama Trip Report and all photos by Crammy Wanyama Black-headed Gonolek a member of the Bush-shrikes family Day 1 – July 7, 2019: Beginning of the tour This tour had uneven arrivals. Two members arrived two days earlier and the six that came in on the night before July 7th, stayed longer; therefore, we had a pre and post- tour to Mabira Forest. For today, we all teamed up and had lunch at our accommodation for the next two nights. This facility has some of the most beautiful gardens around Entebbe; we decided to spend the rest of the afternoon here watching all the birds you would not expect to find around a city garden. Some fascinating ones like the Black-headed Gonolek nested in the garden, White-browed Robin-Chat too did. The trees that surrounded us offered excellent patching spots for the African Hobby. Here we had a Falco patching out in the open for over forty minutes! Superb looks at a Red-chested and Scarlet-chested Sunbirds. The gardens' birdbath attracted African Thrush that reminded the American birders of their American Robin, Yellow- throated Greenbul. Still looking in the trees, we were able to see African Grey Woodpeckers, both Meyer's and Grey Parrot, a pair of Red-headed Lovebirds. While walking around the facility, we got good looks at a flying Shikra and spent ample time with Ross's Turaco that flew back and forth. We had a very lovely Yellow-fronted Tinkerbird on the power lines, Green-backed Camaroptera, a very well sunlit Avian Safaris: Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.aviansafaris.com AVIAN SAFARIS Spectacled Weaver, was added on the Village and Baglafecht Weavers that we had seen earlier and many more. -

Observations of the Nesting Behavior of Rubrica Surinamensi8 (Degeer) (Hymenoptera, Sphecidae)

OBSERVATIONS OF THE NESTING BEHAVIOR OF RUBRICA SURINAMENSI8 (DEGEER) (HYMENOPTERA, SPHECIDAE) BY H. E. EVANS, R. W. VATTHEWS, AND E. McC. CALLAN INTRODUCTION Rubrica surinamensis (DeGeer) is one of the most familiar and well-studied digger wasps of South America. Yet the published accounts of its nesting behavior present a number of puzzling fea- tures. For example, Brthes (I9O2) and Llano (959) reported that females clean the cells of uneaten parts of flies and other debris, but others have not confirmed this. There are many records of females preying upon flies, but Callan (I95O) has reported the occasional use of Lepidoptera and Odonata, a striking exception to the usual prey constancy of solitary wasps. Also Brthes (I9O2) reported that the cocoons contain only two pores, although other Bembicini in this size range make 5-o pores per cocoon. A fuller summary of published observations has been presented by Evans (1966). In the hope of clarifying these and other problems relating to this widely distributed and apparently very successful species, the three of us have pooled our notes on three widely separated populations. One of us (EMC) resided in Trinidad for several years, and had an opportunity to observe a nesting aggregation in the hard, sandy driveway of his house near the Imperial College of Tropical Agri- culture at St. Augustine, a residential area about I3 km east of Port of Spain. Two of us (HEE and RWM) visited Colombia .and Argentina in January and February, I972, and encountered the species in some abundance in both countries. Studies in Colombia were conducted .on a large aggregation in a hard, gravel road on a denuded and eroded hillside just west of the city of Call. -

Phylogenetic Relationships of African Green Snakes

HERPETOLOGICAL JOURNAL 19: 00–00, 2009 Phylogenetic relationships of African green snakes (genera Philothamnus and Hapsidophrys) from São Tomé, Príncipe and Annobon islands based on mtDNA sequences, and comments on their colonization and taxonomy José Jesus1,2, Zoltán T. Nagy3, William R. Branch4, Michael Wink5, Antonio Brehm1 & D. James Harris6 1Human Genetics Laboratory, University of Madeira, Portugal 2Centre for Environmental Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Lisbon, Portugal 3Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels, Belgium 4Bayworld, Hume Wood, South Africa 5Institute of Pharmacy and Molecular Biotechnology, Heidelberg University, Germany 6Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos (CIBIO/UP) and Departamento de Zoologia–Antropologia, Universidade do Porto, Portugal Mitochondrial sequences (16S rRNA and cytochrome b) of the colubrine snake genera Philothamnus and Hapsidophrys were analysed. Samples were obtained from three volcanic islands in the Gulf of Guinea. The main objective was to infer phylogenetic relationships between the taxa and to trace back the colonization patterns of the group. Both insular species, Philothamnus girardi and Philothamnus thomensis, form a monophyletic unit indicating a single colonization event of one island (probably São Tomé) followed by dispersal to Annobon. Genetic divergence was found to be relatively low when compared with other Philothamnus species from the African mainland, but sufficient to consider the two taxa as distinct sister species. Here we also present evidence on the distinct phylogenetic position of Hapsidophrys sp. from the island of Príncipe, which should be considered as a distinct species, Hapsidophrys principis, a sister taxon of H. smaragdina. Key words: 16S rRNA, cytochrome b, Gulf of Guinea islands, Hapsidophrys principis, Philothamnus girardi, Philothamnus thomensis INTRODUCTION The islands of the Gulf of Guinea belong biogeographically to the West African rainforest zone. -

Alexander Sánchez-Ruiz

ARTÍCULO: CURRENT TAXONOMIC STATUS OF THE FAMILY CAPONIIDAE (ARACHNIDA, ARANEAE) IN CUBA WITH THE DESCRIPTION OF TWO NEW SPECIES Alexander Sánchez-Ruiz Abstract: All information known about the spider species of the family Caponiidae recorded from Cuba is compiled. Two new species of the genus Nops MacLeay, 1839 (Araneae, Caponiidae) are described from eastern Cuba, raising to seven the number of species in the Caponiidae fauna of this archipelago. Key words: Araneae, Caponiidae, taxonomy, West Indies, Cuba. Taxonomy: Nops enae sp. n. Nops siboney sp. n. ARTÍCULO: Current taxonomic status of the Estado taxonómico actual de la familia Caponiidae (Arachnida, Araneae) en family Caponiidae (Arachnida, Cuba y descripción de dos especies nuevas Araneae) in Cuba with the description of two new species Resumen: Se recopila toda la información conocida acerca de las especies de arañas de la familia Alexander Sánchez-Ruiz Caponiidae registradas para Cuba. Se describen dos nuevas especies del género Nops Centro Oriental de Ecosistemas y MacLeay, 1839 (Araneae, Caponiidae) procedentes del oriente de Cuba, alcanzando las Biodiversidad, Museo de Historia siete especies la fauna de Caponiidae de este archipiélago. Natural “Tomás Romay”, José A. Palabras clave: Araneae, Caponiidae, taxonomía, Antillas, Cuba. Saco # 601, Santiago de Cuba Taxonomía: 90100, Cuba. Nops enae sp. n. [email protected] Nops siboney sp. n. Revista Ibérica de Aracnología ISSN: 1576 - 9518. Dep. Legal: Z-2656-2000. Introduction Vol. 9, 30-VI-2004 Sección: Artículos y Notas. The family Caponiidae in the New World is represented by nine genera: Calponia Pp: 95–102. Platnick 1993, Caponina Simon, 1891, Nops MacLeay, 1839, Nopsides Chamberlin, 1924, Notnops Platnick, 1994, Orthonops Chamberlin, 1924, Taintnops Platnick, Edita: 1994, Tarsonops Chamberlin, 1924 and Tisentnops Platnick, 1994. -

Arquivos De Zoologia MUSEU DE ZOOLOGIA DA UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO

Arquivos de Zoologia MUSEU DE ZOOLOGIA DA UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO ISSN 0066-7870 ARQ. ZOOL. S. PAULO 37(1):1-139 12.11.2002 A SYNONYMIC CATALOG OF THE NEOTROPICAL CRABRONIDAE AND SPHECIDAE (HYMENOPTERA: APOIDEA) SÉRVIO TÚLIO P. A MARANTE Abstract A synonymyc catalogue for the species of Neotropical Crabronidae and Sphecidae is presented, including all synonyms, geographical distribution and pertinent references. The catalogue includes 152 genera and 1834 species (1640 spp. in Crabronidae, 194 spp. in Sphecidae), plus 190 species recorded from Nearctic Mexico (168 spp. in Crabronidae, 22 spp. in Sphecidae). The former Sphecidae (sensu Menke, 1997 and auct.) is divided in two families: Crabronidae (Astatinae, Bembicinae, Crabroninae, Pemphredoninae and Philanthinae) and Sphecidae (Ampulicinae and Sphecinae). The following subspecies are elevated to species: Podium aureosericeum Kohl, 1902; Podium bugabense Cameron, 1888. New names are proposed for the following junior homonyms: Cerceris modica new name for Cerceris modesta Smith, 1873, non Smith, 1856; Liris formosus new name for Liris bellus Rohwer, 1911, non Lepeletier, 1845; Liris inca new name for Liris peruanus Brèthes, 1926 non Brèthes, 1924; and Trypoxylon guassu new name for Trypoxylon majus Richards, 1934 non Trypoxylon figulus var. majus Kohl, 1883. KEYWORDS: Hymenoptera, Sphecidae, Crabronidae, Catalog, Taxonomy, Systematics, Nomenclature, New Name, Distribution. INTRODUCTION years ago and it is badly outdated now. Bohart and Menke (1976) cleared and updated most of the This catalog arose from the necessity to taxonomy of the spheciform wasps, complemented assess the present taxonomical knowledge of the by a series of errata sheets started by Menke and Neotropical spheciform wasps1, the Crabronidae Bohart (1979) and continued by Menke in the and Sphecidae. -

Guidelines for the Capture and Management of Digital Zoological Names Information Francisco W

Guidelines for the Capture and Management of Digital Zoological Names Information Francisco W. Welter-Schultes Version 1.1 March 2013 Suggested citation: Welter-Schultes, F.W. (2012). Guidelines for the capture and management of digital zoological names information. Version 1.1 released on March 2013. Copenhagen: Global Biodiversity Information Facility, 126 pp, ISBN: 87-92020-44-5, accessible online at http://www.gbif.org/orc/?doc_id=2784. ISBN: 87-92020-44-5 (10 digits), 978-87-92020-44-4 (13 digits). Persistent URI: http://www.gbif.org/orc/?doc_id=2784. Language: English. Copyright © F. W. Welter-Schultes & Global Biodiversity Information Facility, 2012. Disclaimer: The information, ideas, and opinions presented in this publication are those of the author and do not represent those of GBIF. License: This document is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0. Document Control: Version Description Date of release Author(s) 0.1 First complete draft. January 2012 F. W. Welter- Schultes 0.2 Document re-structured to improve February 2012 F. W. Welter- usability. Available for public Schultes & A. review. González-Talaván 1.0 First public version of the June 2012 F. W. Welter- document. Schultes 1.1 Minor editions March 2013 F. W. Welter- Schultes Cover Credit: GBIF Secretariat, 2012. Image by Levi Szekeres (Romania), obtained by stock.xchng (http://www.sxc.hu/photo/1389360). March 2013 ii Guidelines for the management of digital zoological names information Version 1.1 Table of Contents How to use this book ......................................................................... 1 SECTION I 1. Introduction ................................................................................ 2 1.1. Identifiers and the role of Linnean names ......................................... 2 1.1.1 Identifiers .................................................................................. -

Systematic and Taxonomic Issues Concerning Some East African Bird Species, Notably Those Where Treatment Varies Between Authors

Scopus 34: 1–23, January 2015 Systematic and taxonomic issues concerning some East African bird species, notably those where treatment varies between authors Donald A. Turner and David J. Pearson Summary The taxonomy of various East African bird species is discussed. Fourteen of the non- passerines and forty-eight of the passerines listed in Britton (1980) are considered, with reference to treatments by various subsequent authors. Twenty-three species splits are recommended from the treatment in Britton (op. cit.), and one lump, the inclusion of Jackson’s Hornbill Tockus jacksoni as a race of T. deckeni. Introduction With a revision of Britton (1980) now nearing completion, this is the first of two pa- pers highlighting the complexities that surround some East African bird species. All appear in Britton in one form or another, but since that landmark publication our knowledge of East African birds has increased considerably, and with the advances in DNA sequencing, our understanding of avian systematics and taxonomy is con- tinually moving forward. A tidal wave of phylogenetic studies in the last decade has revolutionized our understanding of the higher-level relationships of birds. Taxa pre- viously regarded as quite distantly related have been brought together in new clas- sifications and some major groups have been split asunder (Knox 2014). As a result we are seeing the familiar order of families and species in field guides and checklists plunged into turmoil. The speed at which molecular papers are being published continues at an unprec- edented rate. We must remember, however, that while many molecular results may indicate a relationship, they do not necessarily prove one.