Threats Faced by Maldivian Manta Rays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educators' Resource Guide

EDUCATORS' RESOURCE GUIDE Produced and published by 3D Entertainment Distribution Written by Dr. Elisabeth Mantello In collaboration with Jean-Michel Cousteau’s Ocean Futures Society TABLE OF CONTENTS TO EDUCATORS .................................................................................................p 3 III. PART 3. ACTIVITIES FOR STUDENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................p 4 ACTIVITY 1. DO YOU Know ME? ................................................................. p 20 PLANKton, SOURCE OF LIFE .....................................................................p 4 ACTIVITY 2. discoVER THE ANIMALS OF "SECRET OCEAN" ......... p 21-24 ACTIVITY 3. A. SECRET OCEAN word FIND ......................................... p 25 PART 1. SCENES FROM "SECRET OCEAN" ACTIVITY 3. B. ADD color to THE octoPUS! .................................... p 25 1. CHristmas TREE WORMS .........................................................................p 5 ACTIVITY 4. A. WHERE IS MY MOUTH? ..................................................... p 26 2. GIANT BasKET Star ..................................................................................p 6 ACTIVITY 4. B. WHat DO I USE to eat? .................................................. p 26 3. SEA ANEMONE AND Clown FISH ......................................................p 6 ACTIVITY 5. A. WHO eats WHat? .............................................................. p 27 4. GIANT CLAM AND ZOOXANTHELLAE ................................................p -

(Mobula Alfredi) Feeding Habitat in the Dampier Strait, Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia 1Adi I

Plankton abundance and community structure in reef manta ray (Mobula alfredi) feeding habitat in the Dampier Strait, Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia 1Adi I. Thovyan, 1,2Ricardo F. Tapilatu, 1,2Vera Sabariah, 3,4Stephanie K. Venables 1 Environmental Science Master Program, Graduate School University of Papua (UNIPA) Manokwari, Papua Barat, Indonesia; 2 Research Center of Pacific Marine Resources and Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Science, University of Papua (UNIPA), Manokwari, Papua Barat, Indonesia; 3 Marine Megafauna Foundation, Truckee, California, USA; 4 Centre for Evolutionary Biology, University of Western Australia, Crawley, Australia. Corresponding author: R. F. Tapilatu, [email protected] Abstract. Reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) are pelagic filter feeders, primarily feeding on zooplankton. Plankton plays an important role in marine food webs and can be used as a bioindicator to evaluate water quality and primary productivity. This study aimed to determine the community structure and abundance of zooplankton and phytoplankton at a M. alfredi feeding habitat in the Dampier Strait region of Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia. Plankton samples were collected and environmental conditions were recorded during two sampling sessions, in March and in July 2017, respectively, from five M. alfredi feeding sites using a 20 μm plankton tow net. Plankton richness was found to be higher in March (272 ind L-1±342) than in July (31 ind L-1±11), which may be due to seasonal variations in ocean current patterns in the Dampier Strait. Copepods (Phylum Arthropoda) were the dominant zooplankton found in samples in both sampling periods. Microplastics were also present in tows from both sampling periods, presenting a cause for concern regarding the large filter feeding species, including M. -

MANTA RAYS Giant Manta (Manta Birostris), Reef Manta (Manta Alfredi), and Manta Cf

MANTA RAYS Giant manta (Manta birostris), reef manta (Manta alfredi), and Manta cf. birostris proposed for Annex 3 The largest genus of rays with an especially conservative life history Overview The giant manta ray and the reef manta ray, with a third putative species endemic to the Caribbean region, are the largest ray species attaining sizes over five meters disk width. They have especially conservative life histories, rendering them vulnerable to depletion. Despite evidence for long migrations, regional populations appear to be small, sparsely distributed, and fragmented, meaning localized declines are unlikely mitigated by immigration. Two manta ray species have recently been reassessed for the IUCN Red List and both are considered to be ‘Vulnerable’ on this listing. Giant mantas were also recently listed on Appendix I and II under the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), and both species are listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES). Listing of manta rays in Annex 3 of SPAW would thus be consistent with international agreements and would be compliant with criteria 4 (IUCN), 5 (CITES) and 6 (regional cooperation). Criterion 1 is met due to the decline and fragmentation of the populations. • Exceptionally vulnerable rays due to extremely slow reproduction • Regional small, sparsely distributed, and fragmented populations • Subject to overfishing due to increasing demand for gill plates for Chinese medicine • Included on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as “Vulnerable” • Listed on Appendix II of CITES, Appendix I of CMS, and the CMS MoU sharks © FAO Biology and distribution Manta rays are migratory The giant manta and reef manta can reach disc widths of 700 cm and 500 cm, respectively. -

Marine Protected Species Identification Guide

Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Marine protected species identification guide June 2021 Fisheries Occasional Publication No. 129, June 2021. Prepared by K. Travaille and M. Hourston Cover: Hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata). Photo: Matthew Pember. Illustrations © R.Swainston/www.anima.net.au Bird images donated by Important disclaimer The Chief Executive Officer of the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development and the State of Western Australia accept no liability whatsoever by reason of negligence or otherwise arising from the use or release of this information or any part of it. Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Gordon Stephenson House 140 William Street PERTH WA 6000 Telephone: (08) 6551 4444 Website: dpird.wa.gov.au ABN: 18 951 343 745 ISSN: 1447 - 2058 (Print) ISBN: 978-1-877098-22-2 (Print) ISSN: 2206 - 0928 (Online) ISBN: 978-1-877098-23-9 (Online) Copyright © State of Western Australia (Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development), 2021. ii Marine protected species ID guide Contents About this guide �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������1 Protected species legislation and international agreements 3 Reporting interactions ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������4 Marine mammals �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 Relative size of cetaceans �������������������������������������������������������������������������5 -

Conservation and Population Ecology of Manta Rays in the Maldives

Conservation and Population Ecology of Manta Rays in the Maldives Guy Mark William Stevens Doctor of Philosophy University of York Environment August 2016 2 Abstract This multi-decade study on an isolated and unfished population of manta rays (Manta alfredi and M. birostris) in the Maldives used individual-based photo-ID records and behavioural observations to investigate the world’s largest known population of M. alfredi and a previously unstudied population of M. birostris. This research advances knowledge of key life history traits, reproductive strategies, population demographics and habitat use of M. alfredi, and elucidates the feeding and mating behaviour of both manta species. M. alfredi reproductive activity was found to vary considerably among years and appeared related to variability in abundance of the manta’s planktonic food, which in turn may be linked to large-scale weather patterns such as the Indian Ocean Dipole and El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Key to helping improve conservation efforts of M. alfredi was my finding that age at maturity for both females and males, estimated at 15 and 11 years respectively, appears up to 7 – 8 years higher respectively than previously reported. As the fecundity of this species, estimated at one pup every 7.3 years, also appeared two to more than three times lower than estimates from studies with more limited data, my work now marks M. alfredi as one of the world’s least fecund vertebrates. With such low fecundity and long maturation, M. alfredi are extremely vulnerable to overfishing and therefore needs complete protection from exploitation across its entire global range. -

Technical Letter

February 13, 2019 Margaret H. Miller Natural Resource Management Specialist National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries U.S. Department of Commerce 315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910 Re: Critical habitat designation for the giant manta ay Dear Ms. Miller: As the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) reviews potential locations to designate as critical habitat for the giant manta ray (Mobula birostris, previously Manta birostris), Defenders of Wildlife and the Center for Biological Diversity urge the agency to complete this legally required task as soon as possible and to designate all areas within U.S. jurisdiction currently occupied or unoccupied by the species that are essential to its conservation, including important aggregation sites, as critical habitat. Moreover, to help ensure the species’ conservation, i.e. recovery to the point at which Endangered Species Act (ESA or Act) protections are no longer necessary, NMFS must develop a robust recovery plan as quickly as possible. I. Introduction Pursuant to section 4 of the ESA, 16 U.S.C. § 1533, on November 10, 2015, Defenders petitioned the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, acting through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and NMFS, to add the giant manta ray and two other manta ray species as endangered or threatened. Defenders of Wildlife, A Petition to List the Giant Manta Ray (Manta birostris), Reef Manta Ray (Manta alfredi), and Caribbean Manta Ray (Manta c.f. birostris) as Endangered, or Alternatively as Threatened, Species Pursuant to the Endangered Species Act and for the Concurrent Designation of Critical Habitat (Nov. 10, 2015) (“Listing Petition”). After several rounds of agency and public review required by the ESA, see 16 U.S.C. -

Mobulid Rays) Are Slow-Growing, Large-Bodied Animals with Some Species Occurring in Small, Highly Fragmented Populations

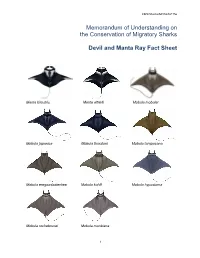

CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks Devil and Manta Ray Fact Sheet Manta birostris Manta alfredi Mobula mobular Mobula japanica Mobula thurstoni Mobula tarapacana Mobula eregoodootenkee Mobula kuhlii Mobula hypostoma Mobula rochebrunei Mobula munkiana 1 CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e . Class: Chondrichthyes Order: Rajiformes Family: Rajiformes Manta alfredi – Reef Manta Ray Mobula mobular – Giant Devil Ray Mobula japanica – Spinetail Devil Ray Devil and Manta Rays Mobula thurstoni – Bentfin Devil Ray Raie manta & Raies Mobula Mobula tarapacana – Sicklefin Devil Ray Mantas & Rayas Mobula Mobula eregoodootenkee – Longhorned Pygmy Devil Ray Species: Mobula hypostoma – Atlantic Pygmy Devil Illustration: © Marc Dando Ray Mobula rochebrunei – Guinean Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula munkiana – Munk’s Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula kuhlii – Shortfin Devil Ray 1. BIOLOGY Devil and manta rays (family Mobulidae, the mobulid rays) are slow-growing, large-bodied animals with some species occurring in small, highly fragmented populations. Mobulid rays are pelagic, filter-feeders, with populations sparsely distributed across tropical and warm temperate oceans. Currently, nine species of devil ray (genus Mobula) and two species of manta ray (genus Manta) are recognized by CMS1. Mobulid rays have among the lowest fecundity of all elasmobranchs (1 young every 2-3 years), and a late age of maturity (up to 8 years), resulting in population growth rates among the lowest for elasmobranchs (Dulvy et al. 2014; Pardo et al 2016). 2. DISTRIBUTION The three largest-bodied species of Mobula (M. japanica, M. tarapacana, and M. thurstoni), and the oceanic manta (M. birostris) have circumglobal tropical and subtropical geographic ranges. The overlapping range distributions of mobulids, difficulty in differentiating between species, and lack of standardized reporting of fisheries data make it difficult to determine each species’ geographical extent. -

Novel Signature Fatty Acid Profile of the Giant Manta Ray Suggests Reliance on an Uncharacterised Mesopelagic Food Source Low In

Novel signature fatty acid profile of the giant manta ray suggests reliance on an uncharacterised mesopelagic food source low in polyunsaturated fatty acids Katherine B. Burgess, Michel Guerrero, Andrea D. Marshall, Anthony J. Richardson, Mike B. Bennett, Lydie I. E. Couturier To cite this version: Katherine B. Burgess, Michel Guerrero, Andrea D. Marshall, Anthony J. Richardson, Mike B. Bennett, et al.. Novel signature fatty acid profile of the giant manta ray suggests reliance on an uncharacterised mesopelagic food source low in polyunsaturated fatty acids. PLoS ONE, Public Library of Science, 2018, 13 (1), pp.e0186464. 10.1371/journal.pone.0186464. hal-02614268 HAL Id: hal-02614268 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02614268 Submitted on 20 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. RESEARCH ARTICLE Novel signature fatty acid profile of the giant manta ray suggests reliance on an uncharacterised mesopelagic food source low in polyunsaturated fatty acids Katherine B. Burgess1,2,3*, Michel Guerrero4, Andrea D. Marshall2, Anthony J. -

Marine Wildlife of WA's North-West Identification Guide

Marine wildlife of WA’s north-west IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Protecting Western Australia’s marine wonders The marine waters between Ningaloo Marine Park and the Northern Territory border are of great significance. The Ningaloo Coast was World Heritage-listed in 2011 for the area’s outstanding natural beauty and exceptional biological richness. The Pilbara Islands and coastal waters provide important habitat for marine turtles, marine mammals, shorebirds and seabirds. The Kimberley region is one of the last great wilderness areas remaining in the world. This guide has been produced by the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) to provide information about marine parks in WA’s north-west and significant or threatened fauna in this region. Top tips for conserving marine life • When boating, ‘go slow for marine life below’, especially over seagrass beds, shallow and muddy areas and in channels where dugongs, turtles and other marine wildlife feed. • Anchor only in sand to protect fragile reef, sponge and seagrass communities. • Support a ‘clean marine’ environment and prevent marine animals from suffering a slow death. Take your rubbish (such as discarded fishing gear, bait straps, plastic bags and bottles) home and if you find any material floating at sea or along the coast, please pick it up. • When in a marine park know your zones. Some zones are set aside as sanctuaries Gaskell Photo – Johnny where you can look but not take (these areas are fantastic spots to go snorkelling, as they have especially abundant marine life). Manta Rays. Manta Rays. • If you find a stranded, sick or injured dolphin, dugong, turtle, whale or seabird, please call the department’s Wildcare Helpline on (08) 9474 9055. -

Protected Species Update

Protected Species Update Reserve Advisory Council Meeting Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve Susan Pultz Pacific Islands Regional Office Protected Resources Division [email protected] 808-725-5150 July 28, 2016 1 Proposed Humpback Whale Delisting; Possibility of Approach Regulations under the MMPA Photo by Doug Perrine/HWRF/Seapics.com/NOAA Fisheries Permit #882 Proposal to Revise ESA Listing Proposed rule to separate humpback whale species into 14 Distinct Population Segments – April 21, 2015 • Humpback whales in Hawaii designated as “Hawaii DPS” • Hawaii DPS not proposed as endangered or threatened Proposed Humpback Whale Hawaii DPS Two Endangered DPSs (pink), Two Threatened DPSs (yellow) Hawaii DPS: Not Listed Humpback Whale Approach Regulations Currently, within 200 nm of shore, it is illegal to do the following: 1. Operate an aircraft within 1,000 feet of any humpback whale; 2. Approach, by any means, within 100 yards of any humpback whale; 3. Cause a vessel, or other object to approach within 100 yards of a humpback whale; and 4. Disrupt the normal behavior or prior activity of a whale by any act or omission. There are also approach regulations in the HIHWNMS, and state approach laws. Humpback Whale Approach Regulations • If humpback whales are no longer listed, Federal ESA approach regulations will no longer be in effect (because implemented under the ESA only) • ESA approach regulations were first implemented in 1987 as an Interim Rule, finalized in 1995 • State (0-3 nm) and Sanctuary approach regulations -

Mobulid Rays Reef Manta and Devil Rays

Fact sheet for the 11th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP11) to the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) Mobulid Rays Reef Manta and Devil Rays Reef Manta Ray Manta alfredi Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula eregoodootenkee Giant Devil Ray Mobula mobular Shortfin Devil Ray Mobula kuhlii Spinetail Devil Ray Mobula japanica Atlantic Devil Ray Mobula hypostoma Bentfin Devil Ray Mobula thurstoni Lesser Guinean Devil Ray Mobula rochebrunei Chilean Devil Ray Mobula tarapacana Munk’s Devil Ray Mobula munkiana Proposed action Inclusion on CMS Appendices I & II Proponents Fiji YAP BARTOSZ CIEŚLAK/WIKIPEDIA COMMONS YAP Overview Manta and Devil Ray species (family Mobulidae) share an inherent vulnerability to overexploitation due to exceptionally low productivity and aggregating behavior. Around the world, these large, migratory rays are facing intense targeted and incidental fishing pressure, increasingly driven by escalating Chinese demand for their gill plates. This largely unregulated mortality risks population and ecosystem health, as well as threatening substantial revenue possible through tourism. Inclusion in CMS Appendices I & II is warranted to prevent long-standing depletion, bolster existing national safeguards, preserve economic and ecological benefits, and improve the understanding of species status. Such action will also complement the CMS Appendices I & II listing for the Giant Manta Ray (Manta birostris), and the listing of Manta species under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). SHARK ADVOCATES INTERNATIONAL Fact sheet for the 11th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP11) to the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) Biology and Distribution and Northern Mariana Islands), and Australia (Christmas Mobulid rays occur in the world’s tropical and temperate Island and Cocos Keeling Islands). -

Infografis Manta

MANTA RAY CONSERVATION SUSTAINING THE NATURE THAT SUSTAINS INDONESIA FACTS ABOUT MANTA RAYS MANTA RAYS IN INDONESIA Two manta ray species: Manta rays feed on Sangalaki, East Kalimantan Reef manta ray (Manta zooplankton (tiny animals alfredi) and the Oceanic that drift in ocean currents). Raja Ampat, West Papua manta ray (Manta birostris) Highly vulnerable as they have extremely low Nusa Penida,Bali Manta rays are the largest reproductive rates – Komodo Island,Flores rays in the world. Reef female mantas reach mantas can grow up to sexual maturity at 4.5 meters, while Oceanic 8-10 years old, and give mantas can reach a birth to only one pup Both Reef and Oceanic manta rays live in Indonesian waters. massive 8-meter wingspan. every 2-5 years. Raja Ampat is one of the only places in the world where both species of manta can be encountered Manta rays are very at the same place and time. intelligent and have the largest brain to body ratio In 2015, CI discovered South East Asia’s first manta of any fish. They are a ray nursery in Wayag Lagoon in Raja Ampat, West Papua. social, gentle, and highly curious species. Manta rays can be found throughout Indonesia, Manta rays can live up to with key populations in Sangalaki (East Kalimantan), 50 years. Nusa Penida (Bali), Komodo (Flores) and Manta rays are harmless. They do not Raja Ampat (West Papua). have a barb on their tail, and cannot sting. Manta rays seen in tourist sites Nusa Penida and Komodo migrate through Tanjung Luar (West Nusa Tenggara) and Lamakera (East Nusa Tenggara), the biggest known manta hunting areas in Indonesia.