Marine Wildlife of WA's North-West Identification Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educators' Resource Guide

EDUCATORS' RESOURCE GUIDE Produced and published by 3D Entertainment Distribution Written by Dr. Elisabeth Mantello In collaboration with Jean-Michel Cousteau’s Ocean Futures Society TABLE OF CONTENTS TO EDUCATORS .................................................................................................p 3 III. PART 3. ACTIVITIES FOR STUDENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................p 4 ACTIVITY 1. DO YOU Know ME? ................................................................. p 20 PLANKton, SOURCE OF LIFE .....................................................................p 4 ACTIVITY 2. discoVER THE ANIMALS OF "SECRET OCEAN" ......... p 21-24 ACTIVITY 3. A. SECRET OCEAN word FIND ......................................... p 25 PART 1. SCENES FROM "SECRET OCEAN" ACTIVITY 3. B. ADD color to THE octoPUS! .................................... p 25 1. CHristmas TREE WORMS .........................................................................p 5 ACTIVITY 4. A. WHERE IS MY MOUTH? ..................................................... p 26 2. GIANT BasKET Star ..................................................................................p 6 ACTIVITY 4. B. WHat DO I USE to eat? .................................................. p 26 3. SEA ANEMONE AND Clown FISH ......................................................p 6 ACTIVITY 5. A. WHO eats WHat? .............................................................. p 27 4. GIANT CLAM AND ZOOXANTHELLAE ................................................p -

(Mobula Alfredi) Feeding Habitat in the Dampier Strait, Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia 1Adi I

Plankton abundance and community structure in reef manta ray (Mobula alfredi) feeding habitat in the Dampier Strait, Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia 1Adi I. Thovyan, 1,2Ricardo F. Tapilatu, 1,2Vera Sabariah, 3,4Stephanie K. Venables 1 Environmental Science Master Program, Graduate School University of Papua (UNIPA) Manokwari, Papua Barat, Indonesia; 2 Research Center of Pacific Marine Resources and Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Science, University of Papua (UNIPA), Manokwari, Papua Barat, Indonesia; 3 Marine Megafauna Foundation, Truckee, California, USA; 4 Centre for Evolutionary Biology, University of Western Australia, Crawley, Australia. Corresponding author: R. F. Tapilatu, [email protected] Abstract. Reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) are pelagic filter feeders, primarily feeding on zooplankton. Plankton plays an important role in marine food webs and can be used as a bioindicator to evaluate water quality and primary productivity. This study aimed to determine the community structure and abundance of zooplankton and phytoplankton at a M. alfredi feeding habitat in the Dampier Strait region of Raja Ampat, West Papua, Indonesia. Plankton samples were collected and environmental conditions were recorded during two sampling sessions, in March and in July 2017, respectively, from five M. alfredi feeding sites using a 20 μm plankton tow net. Plankton richness was found to be higher in March (272 ind L-1±342) than in July (31 ind L-1±11), which may be due to seasonal variations in ocean current patterns in the Dampier Strait. Copepods (Phylum Arthropoda) were the dominant zooplankton found in samples in both sampling periods. Microplastics were also present in tows from both sampling periods, presenting a cause for concern regarding the large filter feeding species, including M. -

MANTA RAYS Giant Manta (Manta Birostris), Reef Manta (Manta Alfredi), and Manta Cf

MANTA RAYS Giant manta (Manta birostris), reef manta (Manta alfredi), and Manta cf. birostris proposed for Annex 3 The largest genus of rays with an especially conservative life history Overview The giant manta ray and the reef manta ray, with a third putative species endemic to the Caribbean region, are the largest ray species attaining sizes over five meters disk width. They have especially conservative life histories, rendering them vulnerable to depletion. Despite evidence for long migrations, regional populations appear to be small, sparsely distributed, and fragmented, meaning localized declines are unlikely mitigated by immigration. Two manta ray species have recently been reassessed for the IUCN Red List and both are considered to be ‘Vulnerable’ on this listing. Giant mantas were also recently listed on Appendix I and II under the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), and both species are listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES). Listing of manta rays in Annex 3 of SPAW would thus be consistent with international agreements and would be compliant with criteria 4 (IUCN), 5 (CITES) and 6 (regional cooperation). Criterion 1 is met due to the decline and fragmentation of the populations. • Exceptionally vulnerable rays due to extremely slow reproduction • Regional small, sparsely distributed, and fragmented populations • Subject to overfishing due to increasing demand for gill plates for Chinese medicine • Included on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as “Vulnerable” • Listed on Appendix II of CITES, Appendix I of CMS, and the CMS MoU sharks © FAO Biology and distribution Manta rays are migratory The giant manta and reef manta can reach disc widths of 700 cm and 500 cm, respectively. -

Australian Ramsar Site Guidelines

AUSTRALIAN RAMSAR SITE NOMINATION GUIDELINES Module 4 of the National Guidelines for Ramsar Wetlands— Implementing the Ramsar Convention in Australia WAT251.0912 Published by While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population the contents of this publication are factually correct, the and Communities Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy GPO Box 787 or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable CANBERRA ACT 2601 for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Endorsement Endorsed by the Standing Council on Environment and Citation Water, 2012. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population Copyright © Commonwealth of Australia 2012 and Communities (2012). Australian Ramsar Site Nomination Guidelines. Module 4 of the National Guidelines for Ramsar Information contained in this publication may be copied or Wetlands—Implementing the Ramsar Convention in Australia. reproduced for study, research, information or educational Australian Government Department of Sustainability, purposes, subject to inclusion of an acknowledgment of the Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Canberra. source. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: ISBN: 978-1-921733-66-6 Assistant Secretary The publication can be accessed at http://www.environment. Aquatic Systems Policy Branch gov.au/water/topics/wetlands/ramsar-convention/australian- -

Fact Sheet: Eighty Mile Beach

Fact Sheet: Eighty Mile Beach Region North Coast Summary Imagine an isolated beach of endless white sand, seashells and turquoise waters, stretching so far it would take more than a week to walk its length. Aptly named, Eighty Mile Beach is indeed long, stretching 220 kilometres and renowned as Australia's longest uninterrupted beach. With its midpoint halfway between Broome and Port Hedland, Eighty Mile Beach is like no other beach in Australia – where the desert (Great Sandy Desert) meets the sea (Indian Ocean). It differentiates itself from other beaches with its low windswept dunes, an almost continuous curving coastline, and large tidal ranges that expose some 60,000 hectares of sand and mudflats, widening the intertidal zone at low tide to almost four kilometres in some sections. Generated on 27/09/2021 https://marinewaters.fish.wa.gov.au/resource/fact-sheet-eighty-mile-beach/ Page 1 of 7 Figure 1. The wide expanse of the intertidal zone as the tide returns on Eighty mile beach (Image: Tahryn Thompson) The seascape is even more remarkable due to an extraordinary diversity of marine life, which includes up to 400,000 migratory shorebirds, rich benthic (mud) fauna, breeding turtles and the world’s largest stocks of wild pearl shell. The shorebirds and marine life of this wetland are recognised internationally under the Ramsar Convention. Eighty Mile Beach is sea country for the Karajarri people to the north, the Nyangumarta people over most of its length and the Ngarla people in the vicinity of Cape Keraudren. Mythological and ceremonial sites, Aboriginal art, shell middens and fish traps are found throughout the area and each group retains social, spiritual and cultural bonds with their traditional land and sea country. -

Valuation of Disaster Risk Reduction Ecosystem Services of Australia's

Valuation of disaster risk reduction ecosystem services of Australia’s coastal wetlands: review and recommendations REPORT PREPARED BY IDEEA GROUP 14 July 2020 Prepared for Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE) Reference ID: 3600004198 Date 14 July 2020 Institute for the Development of Environmental-Economic Accounting (IDEEA Group) ABN 22 608 437 056 [email protected] www.ideeagroup.com Authors John Finisdore, Dr. Nathan Waltham, Carl Obst, Ben Chipperfield, Reiss Mcleod, and Mark Eigenraam Dr. Roel Plant of UTS provided valuable insights when reviewing this report. Suggested citation IDEEA Group (2020) Valuation of disaster risk reduction ecosystem services of Australia’s coastal wetlands: review and recommendations. Prepared for the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE). Canberra, Australia. Disclaimer This document has been prepared in accordance with the scope of services described in the contract or agreement between IDEEA Group and the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE). This document is supplied in good faith and reflects the knowledge, expertise and experience of the advisors involved. The document and findings are subject to assumptions and limitations referred to within the document. Any findings, conclusions or recommendations only apply to the contract or agreement and no greater reliance should be assumed or drawn by the DAWE. IDEEA Group accepts no responsibility whatsoever for any loss occasioned by any person acting or refraining from action because of reliance on this document. Furthermore, the document has been prepared solely for use by DAWE. IDEEA Group accepts no responsibility for its use by other parties. Page 2 Contents 1 Executive summary ........................................................................................................................ -

Marine Protected Species Identification Guide

Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Marine protected species identification guide June 2021 Fisheries Occasional Publication No. 129, June 2021. Prepared by K. Travaille and M. Hourston Cover: Hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata). Photo: Matthew Pember. Illustrations © R.Swainston/www.anima.net.au Bird images donated by Important disclaimer The Chief Executive Officer of the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development and the State of Western Australia accept no liability whatsoever by reason of negligence or otherwise arising from the use or release of this information or any part of it. Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Gordon Stephenson House 140 William Street PERTH WA 6000 Telephone: (08) 6551 4444 Website: dpird.wa.gov.au ABN: 18 951 343 745 ISSN: 1447 - 2058 (Print) ISBN: 978-1-877098-22-2 (Print) ISSN: 2206 - 0928 (Online) ISBN: 978-1-877098-23-9 (Online) Copyright © State of Western Australia (Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development), 2021. ii Marine protected species ID guide Contents About this guide �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������1 Protected species legislation and international agreements 3 Reporting interactions ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������4 Marine mammals �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 Relative size of cetaceans �������������������������������������������������������������������������5 -

West Canning Basin Allocation Statement

West Canning Basin Allocation statement The West Canning Basin in the To manage water use the Pilbara region of Western Australia Department of Water and is an important water resource Environmental Regulation set for regional development and allocation limits and licensing rules supports both irrigated agriculture for the West Canning Basin in the and mining. Located around 100 Pilbara groundwater allocation plan kilometres east of Port Hedland, (DoW, 2013) and then revised the limits the West Canning Basin covers in 2014 based on new hydrogeology approximately 3500 square and monitoring information. This kilometres and includes the allocation statement replaces section Broome and Wallal aquifers in the 5.3 of this plan and includes a change Canning-Kimberley groundwater to the Wallal unconfined and confined area, and the Wallal aquifer in the aquifers. Pilbara groundwater area. Locality Map Port Hedland Eighty Mile Beach roadhouse Pardoo n Highway Pardoo roadhouse Great Norther station Legend West Canning Basin Pilbara groundwater allocation plan area Groundwater areas Canningimele Pilbara Aquifers 0 10 20 30 40 Broome Kilometres Figure 1: Location and aquifers of the West Canning Basin Current water availability Water demand for irrigated agriculture and mining While there is currently no more water available for has increased significantly in the West Canning licensing from the Wallal aquifer, water is available Basin. Over the last two years, DWER has assessed from the 10 GL/year allocation for the Broome aquifer and licensed water entitlements from the Wallal in the West Canning–Pardoo subarea, though quality aquifer that now total almost 51 GL/year. and yield may vary from site to site (Table 1). -

Conservation and Population Ecology of Manta Rays in the Maldives

Conservation and Population Ecology of Manta Rays in the Maldives Guy Mark William Stevens Doctor of Philosophy University of York Environment August 2016 2 Abstract This multi-decade study on an isolated and unfished population of manta rays (Manta alfredi and M. birostris) in the Maldives used individual-based photo-ID records and behavioural observations to investigate the world’s largest known population of M. alfredi and a previously unstudied population of M. birostris. This research advances knowledge of key life history traits, reproductive strategies, population demographics and habitat use of M. alfredi, and elucidates the feeding and mating behaviour of both manta species. M. alfredi reproductive activity was found to vary considerably among years and appeared related to variability in abundance of the manta’s planktonic food, which in turn may be linked to large-scale weather patterns such as the Indian Ocean Dipole and El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Key to helping improve conservation efforts of M. alfredi was my finding that age at maturity for both females and males, estimated at 15 and 11 years respectively, appears up to 7 – 8 years higher respectively than previously reported. As the fecundity of this species, estimated at one pup every 7.3 years, also appeared two to more than three times lower than estimates from studies with more limited data, my work now marks M. alfredi as one of the world’s least fecund vertebrates. With such low fecundity and long maturation, M. alfredi are extremely vulnerable to overfishing and therefore needs complete protection from exploitation across its entire global range. -

Technical Letter

February 13, 2019 Margaret H. Miller Natural Resource Management Specialist National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries U.S. Department of Commerce 315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910 Re: Critical habitat designation for the giant manta ay Dear Ms. Miller: As the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) reviews potential locations to designate as critical habitat for the giant manta ray (Mobula birostris, previously Manta birostris), Defenders of Wildlife and the Center for Biological Diversity urge the agency to complete this legally required task as soon as possible and to designate all areas within U.S. jurisdiction currently occupied or unoccupied by the species that are essential to its conservation, including important aggregation sites, as critical habitat. Moreover, to help ensure the species’ conservation, i.e. recovery to the point at which Endangered Species Act (ESA or Act) protections are no longer necessary, NMFS must develop a robust recovery plan as quickly as possible. I. Introduction Pursuant to section 4 of the ESA, 16 U.S.C. § 1533, on November 10, 2015, Defenders petitioned the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, acting through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and NMFS, to add the giant manta ray and two other manta ray species as endangered or threatened. Defenders of Wildlife, A Petition to List the Giant Manta Ray (Manta birostris), Reef Manta Ray (Manta alfredi), and Caribbean Manta Ray (Manta c.f. birostris) as Endangered, or Alternatively as Threatened, Species Pursuant to the Endangered Species Act and for the Concurrent Designation of Critical Habitat (Nov. 10, 2015) (“Listing Petition”). After several rounds of agency and public review required by the ESA, see 16 U.S.C. -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

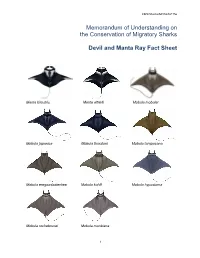

Mobulid Rays) Are Slow-Growing, Large-Bodied Animals with Some Species Occurring in Small, Highly Fragmented Populations

CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks Devil and Manta Ray Fact Sheet Manta birostris Manta alfredi Mobula mobular Mobula japanica Mobula thurstoni Mobula tarapacana Mobula eregoodootenkee Mobula kuhlii Mobula hypostoma Mobula rochebrunei Mobula munkiana 1 CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e . Class: Chondrichthyes Order: Rajiformes Family: Rajiformes Manta alfredi – Reef Manta Ray Mobula mobular – Giant Devil Ray Mobula japanica – Spinetail Devil Ray Devil and Manta Rays Mobula thurstoni – Bentfin Devil Ray Raie manta & Raies Mobula Mobula tarapacana – Sicklefin Devil Ray Mantas & Rayas Mobula Mobula eregoodootenkee – Longhorned Pygmy Devil Ray Species: Mobula hypostoma – Atlantic Pygmy Devil Illustration: © Marc Dando Ray Mobula rochebrunei – Guinean Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula munkiana – Munk’s Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula kuhlii – Shortfin Devil Ray 1. BIOLOGY Devil and manta rays (family Mobulidae, the mobulid rays) are slow-growing, large-bodied animals with some species occurring in small, highly fragmented populations. Mobulid rays are pelagic, filter-feeders, with populations sparsely distributed across tropical and warm temperate oceans. Currently, nine species of devil ray (genus Mobula) and two species of manta ray (genus Manta) are recognized by CMS1. Mobulid rays have among the lowest fecundity of all elasmobranchs (1 young every 2-3 years), and a late age of maturity (up to 8 years), resulting in population growth rates among the lowest for elasmobranchs (Dulvy et al. 2014; Pardo et al 2016). 2. DISTRIBUTION The three largest-bodied species of Mobula (M. japanica, M. tarapacana, and M. thurstoni), and the oceanic manta (M. birostris) have circumglobal tropical and subtropical geographic ranges. The overlapping range distributions of mobulids, difficulty in differentiating between species, and lack of standardized reporting of fisheries data make it difficult to determine each species’ geographical extent.