Gnetum Gnemon (Gentum)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front Cover: Pandanus Odoratissimus L.F Published Quarterly PRINTED IN

Front cover: Pandanus odoratissimus L.f (PHOTO: Y.I. ULUMUDDIN) Published quarterly PRINTED IN INDONESIA ISSN: 1412-033X E-ISSN: 2085-4722 BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X Volume 19, Number 1, January 2018 E-ISSN: 2085-4722 Pages: 77-84 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d190113 Forest gardens management under traditional ecological knowledge in West Kalimantan, Indonesia BUDI WINARNI1,♥, ABUBAKAR M. LAHJIE2,♥♥, B.D.A.S. SIMARANGKIR2, SYAHRIR YUSUF2, YOSEP RUSLIM2,♥♥♥ 1Department of Agricultural Management, Politeknik Pertanian Negeri Samarinda. Jl. Samratulangi, Kampus Sei Keledang, Samarinda 75131, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Tel.: +62-541-260421, Fax.: +62-541-260680, ♥email: [email protected] 2Faculty of Forestry, Universitas Mulawarman. Jl. Ki Hajar Dewantara, PO Box 1013, Gunung Kelua, SamarindaUlu, Samarinda 75116, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Tel.: +62-541-735089, Fax.: +62-541-735379. ♥♥email: [email protected]; ♥♥♥[email protected] Manuscript received: 5 July 2017. Revision accepted: 2 December 2017. Abstract. Winarni B, Lahjie AM, Simarangkir B.D.A.S., Yusuf S, Ruslim Y. 2018. Forest gardens management under traditional ecological knowledge in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 19: 77-84. Local wisdom of Dayak Kodatn people in West Kalimantan in forest management shows that human and nature are in one beneficial ecological unity known as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). Former cultivation forest areas are managed in various ways, including planting forest trees, fruit-producing plants, and rubber trees until they transform -

Nutrient Content of Three Clones of Red Fruit (Pandanus Conoideus) During the Maturity Development

International Food Research Journal 23(3): 1217-1225 (2016) Journal homepage: http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my Nutrient content of three clones of red fruit (Pandanus conoideus) during the maturity development 1*Sarungallo, Z. L., 1Murtiningrum, 1Santoso, B., 1Roreng, M. K. and 1Latumahina, R. M. M. 1Department of Agricultural Technology, Papua University. Jl. Gunung Salju, Amban, Manokwari-98314, West Papua, Indonesia Article history Abstract Received: 23 November 2014 The purpose of this study was to determine the best harvest time of three clones red fruit Received in revised form: (Pandanus conoideus) based on their nutrient contents. Fruit flesh of three red fruit clones 28 August 2015 (namely Monsor, Edewewits and Memeri) were analyzed the nutritional content, during the Accepted: 9 September 2015 development of the maturity i.e. unripe, half ripe, ripe and overripe. The results show that the maturity stages had a significant effect on the nutrient contents of three clones of red fruit. Nutritional components in the red fruit on are fat (50.8-55.58%), carbohydrate (36.78-46.3%), Keywords vitamin C (24-45 mg per 100 g), phosphorus (654-792 ppm), calcium (4919-5176 ppm), total carotenoids (976-1592 ppm) and total tocopherols (1256-2016 ppm). The changed of nutrient Red fruit (Pandanus conoideus) composition of fruits vary in each clone during ripening. Using the principal component Ripening stages analysis (PCA), commonly three clones of red fruit in unripe and half ripe stages could be Carotenoids characterized by high content of ash, calcium, phosphor, and carbohydrate, while red fruit in Tocopherol maturity level of ripe and overripe were characterized by high content of fat, total carotenoids Nutrient composition and total tocopherol content. -

Pandanus Ific Food Leaflet N° Pac 6 ISSN 1018-0966

A publication of the Healthy Pacific Lifestyle Section of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community Pandanus ificifoodileafieiin° Pac i6 ISSN 1018-0966 n parts of the central and northern Pacific, pandanus is a popular food item used in a variety of interesting ways. However, on many other IPacific Islands, pandanus is not well-known as a food. There are many varieties of pandanus, but only In Kiribati, pandanus is called the ‘tree of life’ as it some have edible fruits and nuts. The plants have provides food, shelter and medicine. In the Marshall a distinctive shape and the near-coastal species, Islands, it is called the ‘divine tree’, like coconut, Pandanus tectorius, is found on most Pacific Islands. because of its important role in everyday life. Pandanus The bunches of fruit have many sections called ‘keys’, is also an important staple food in the Federated States which weigh from around 60 to 200 grams each. of Micronesia (FSM), Tuvalu, Tokelau and Papua New (The botanical term for these keys is phalanges, which Guinea. Dried pandanus was once an important food means ‘finger bones’.) People often eat the keys raw, for voyagers on outrigger canoes, enabling seafarers of but the juicy pulp can also be extracted and cooked long ago to survive long journeys. or preserved. The nuts of some varieties are also eaten. In some countries, a number of pandanus varieties are conserved in genebank collections. This leaflet focuses on the Pandanus tectorius species of pandanus. However, other species, such as The pandanus plant plays an important role in Pandanus conoideus and Pandanus jiulianettii, which everyday life in the Pacific. -

Further Interpretation of Wodehouseia Spinata Stanley from the Late Maastrichtian of the Far East (China) M

ISSN 0031-0301, Paleontological Journal, 2019, Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 203–213. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2019. Russian Text © M.V. Tekleva, S.V. Polevova, E.V. Bugdaeva, V.S. Markevich, Sun Ge, 2019, published in Paleontologicheskii Zhurnal, 2019, No. 2, pp. 94–105. Further Interpretation of Wodehouseia spinata Stanley from the Late Maastrichtian of the Far East (China) M. V. Teklevaa, *, S. V. Polevovab, E. V. Bugdaevac, V. S. Markevichc, and Sun Ged aBorissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 117647 Russia bMoscow State University, Moscow, 119991 Russia cFederal Scientific Center of the East Asia Terrestrial Biodiversity, Vladivostok, 690022 Russia dCollege of Paleontology, Shenyang Normal University, Shenyang, Liaoning Province, China *e-mail: [email protected] Received May 25, 2018; revised September 30, 2018; accepted October 15, 2018 Abstract—Dispersed pollen grains Wodehouseia spinata Stanley of unknown botanical affinity from the Maastrichtian of the Amur River Region, Far East are studied using transmitted light, scanning and trans- mission electron microscopy. The pollen was probably produced by wetland or aquatic plants, adapted to a sudden change in the water regime during the vegetation season. The pattern of the exine sculpture and spo- roderm ultrastructure suggests that insects contributed to pollination. The flange and unevenly thickened endexine could facilitate harmomegathy. A tetragonal or rhomboidal tetrad type seems to be most logical for Wodehouseia pollen. The infratectum structure suggests that Wodehouseia should be placed within an advanced group of eudicots. Keywords: Wodehouseia, exine morphology, sporoderm ultrastructure, “oculata” group, Maastrichtian DOI: 10.1134/S0031030119020126 INTRODUCTION that has lost its flange (see a review Wiggins, 1976). -

Seed Plant Phylogeny: Demise of the Anthophyte Hypothesis? Michael J

bb10c06.qxd 02/29/2000 04:18 Page R106 R106 Dispatch Seed plant phylogeny: Demise of the anthophyte hypothesis? Michael J. Donoghue* and James A. Doyle† Recent molecular phylogenetic studies indicate, The first suggestions that Gnetales are related to surprisingly, that Gnetales are related to conifers, or angiosperms were based on several obvious morphological even derived from them, and that no other extant seed similarities — vessels in the wood, net-veined leaves in plants are closely related to angiosperms. Are these Gnetum, and reproductive organs made up of simple, results believable? Is this a clash between molecules unisexual, flower-like structures, which some considered and morphology? evolutionary precursors of the flowers of wind-pollinated Amentiferae, but others viewed as being reduced from Addresses: *Harvard University Herbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA. †Section of Evolution and more complex flowers in the common ancestor of Ecology, University of California, Davis, California 95616, USA. angiosperms, Gnetales and Mesozoic Bennettitales [1]. E-mail: [email protected] These ideas went into eclipse with evidence that simple [email protected] flowers really are a derived, rather than primitive, feature Current Biology 2000, 10:R106–R109 of the Amentiferae, and that vessels arose independently in angiosperms and Gnetales. Vessels in angiosperms 0960-9822/00/$ – see front matter seem derived from tracheids with scalariform pits, whereas © 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. in Gnetales they resemble tracheids with circular bor- dered pits, as in conifers. Gnetales are also like conifers in These are exciting times for those interested in plant lacking scalariform pitting in the primary xylem, and in evolution. -

On the Evolution of Angiosperms in the Himalayan Region: a Summary

The Palaeobotanist 57(2008) : 453-457 0031-0174/2008 $2.00 On the evolution of Angiosperms in the Himalayan region: A summary J.S. GULERIA Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany, 53 University Road, Lucknow 226007, India. [email protected] (Received 10 June, 2007; revised version accepted 15 September, 2008) ABSTRACT Guleria JS 2008. On the evolution of Angiosperms in the Himalayan region: A summary. The Palaeobotanist 57(3): 453-457. The paper summarises the evolution of angiosperms in different zones of Himalaya. The Himalayan Cenozoic flora has been divided age-wise as Palaeogene and Neogene flora. The Himalayan Palaeogene flora is largely a continuation of tropical peninsular flora of India. The early Miocene flora of Lesser Himalaya is also moist tropical. However, temperate plants started appearing during Miocene in the Higher Himalaya and their occurrence in Plio-Pleistocene flora of Kashmir reflect uplift of the Himalaya. The sub-Himalayan flora indicates existence of warm humid conditions in this belt which became drier by the end of Pliocene. The northern floral elements appeared to have invaded India all along the Himalayan belt. Since its birth the Himalaya has played a significant role in the immigration of plants from the adjoining regions, i.e. east, west and north, thereby enriching the Indian flora. The development of the Cenozoic flora of the Himalayan region is an expression of changing patterns of geography, topography and climate. Key-words—Cenozoic, Angiosperms, Himalayan flora, Migration, Climate (India). fgeky;h -

Herbal Medicine: Pandan (Pandanus Tectorius)

For the Month of October Herbal Medicine: Pandan (Pandanus tectorius ) Fragrant Screw Pine The pandan tree grows as tall as 5 meters, with erect, small branches. Pandan is also known as Fragrant Screw Pine. Its trunk bears plenty of prop roots. Its leaves spirals the branches, and crowds at the end. Its male inflorescence emits a fragrant smell, and grows in length for up to 0.5 meters. The fruit of the pandan tree, which is usually about 20 centimeters long, are angular in shape, narrow in the end and the apex is truncate. It grows in the thickets lining the seashores of most places in the Philippines. In various parts of the world, the uses of this plant are very diverse. Some countries concentrate on the culinary uses of pandan, while others deeply rely on its medicinal values. For instance, many Asians regard this food as famine food. Others however mainly associate pandan with the flavoring and nice smell that it secretes. In the Philippines, pandan leaves are being cooked along with rice to in- corporate the flavor and smell to it. As can be observed, the uses of the pandan tree are not limited to cooking uses. Its leaves and roots are found to have medici- nal benefits. Such parts of the plant have been found to have essential oils, tannin, alkaloids and glycosides, which are the reasons for the effective treatment of vari- ous health concerns. It functions as a pain reliever, mostly for headaches and pain caused by arthritis, and even hangover. It can also be used as antiseptic and anti- bacterial, which makes it ideal for healing wounds. -

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity of Melinjo (Gnetum Gnemon L.) Seed Extracts and Molecular Docking of Its Stilbene Constituents

Online - 2455-3891 Vol 10, Issue 3, 2017 Print - 0974-2441 Research Article ANGIOTENSIN CONVERTING ENZYME INHIBITORY ACTIVITY OF MELINJO (GNETUM GNEMON L.) SEED EXTRACTS AND MOLECULAR DOCKING OF ITS STILBENE CONSTITUENTS ABDUL MUN’IM1*, MUHAMMAD ASHAR MUNADHIL1, NURAINI PUSPITASARI1, AZMINAH2, ARRY YANUAR2 1Department of Pharmacognosy-Phytochemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Indonesia, Depok 16424, Indonesia. 2Department of Biomedical Computation, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Indonesia, Depok 16424, Indonesia. Email: [email protected] Received: 10 November 2016, Revised and Accepted: 30 November 2016 ABSTRACT Objectives: To evaluate the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity of melinjo (Gnetum gnemon) seed extract and to study molecular docking of stilbene contained in melinjo seeds. Methods: Melinjo seed powders were extracted with n-hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water successively. The extracts were evaluated ACE inhibitory activities using ACE kit-Wist and the phenolic content using Folin–Ciocalteu method. The extract demonstrated the highest ACE inhibitory activity was subjected to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to know its stilbene constituent. The stilbene constituents in melinjo seed were performed molecular docking using AutoDock Vina, and ligand-receptor Interactions were processed using Ligand Scout. Results: The ethyl acetate extract demonstrated the highest ACE inhibition activity with inhibitory concentration 50% value of 9.77 × 10 −8 μg/mL inhibitor),and the highest as in silicototal phenolicmolecular content docking (575.9 studies mg demonstrated gallic acid equivalent/g). that they fit Ultra-performance into the lisinopril receptors.LC-MS analysis of ethyl acetate extract has detected the existency of resveratrol, gnetin C, ε-viniferin, and gnemonoside A/B. -

Shri R. L. T College of Science, Akola 2019-2020 Department of Botany

Shri R. L. T College of Science, Akola 2019-2020 Department of Botany B. Sc-1 Semester-II Paleobotany, Gymnosperm, Morphology and Utilization of Plants Solve the Following MCQ’s Test Max.Marks:30 Time:60Mins 1) The study of past geological plant life is done in branch called as ….. a)Botany b)Paleobotany c)History d)Anthropology 2)The father of Indian paleobotany is…. a)Homi Bhabha b) C.V. Raman c)Maheshwari d)Birbal Sahani 3) The earth is supposed to be originated before…. a) 4.6 billion years ago b)3.4 billion years ago c) 4.6 million years ago d)none of these 4)The oldest era in which life is originated was on the earth. a)proterozoic era b)Archeozoic era c)Paleozoic era d)Mesozoic era 5)The following era is called as “age of ferns” a)proterozoic era b)Archeozoic era c)paleozoic era d)Mesozoic era 6) The following era is called as era of Modern Life…. a)Coenozoic era b)Archeozoic era c)Paleozoic era d)Mesozoic era 7) Sphenopteris hoeninghausii is the….. a)stem b)root c)leaves d)ovule 8) Root of L.oldhamia is called as…. a) Sphenopteris hoeninghausii b)Kaloxylon hookeri c)Lagenostoma lomaxii d)Rachiopteris aspera 9) Cycadeoidea is also known as…. a)Lyginopteris b)Bennettites c) Pinus d)Gnetum 10) The manoxylic wood refers to........... a)single ring of xylem b)hard and compressed c)loose and soft d)many rings of xylem. 11) Endosperm in gymnosperm is............. a) haploid b)diploid c)triploid d)tetraploid 12) The ovules in gymnosperms are... -

Pacific Colonisation and Canoe Performance: Experiments in the Science of Sailing

PACIFIC COLONISATION AND CANOE PERFORMANCE: EXPERIMENTS IN THE SCIENCE OF SAILING GEOFFREY IRWIN University of Auckland RICHARD G.J. FLAY University of Auckland The voyaging canoe was the primary artefact of Oceanic colonisation, but scarcity of direct evidence has led to uncertainty and debate about canoe sailing performance. In this paper we employ methods of aerodynamic and hydrodynamic analysis of sailing routinely used in naval architecture and yacht design, but rarely applied to questions of prehistory—so far. We discuss the history of Pacific sails and compare the performance of three different kinds of canoe hull representing simple and more developed forms, and we consider the implications for colonisation and later inter-island contact in Remote Oceania. Recent reviews of Lapita chronology suggest the initial settlement of Remote Oceania was not much before 1000 BC (Sheppard et al. 2015), and Tonga was reached not much more than a century later (Burley et al. 2012). After the long pause in West Polynesia the vast area of East Polynesia was settled between AD 900 and AD 1300 (Allen 2014, Dye 2015, Jacomb et al. 2014, Wilmshurst et al. 2011). Clearly canoes were able to transport founder populations to widely-scattered islands. In the case of New Zealand, modern Mäori trace their origins to several named canoes, genetic evidence indicates the founding population was substantial (Penney et al. 2002), and ancient DNA shows diversity of ancestral Mäori origins (Knapp et al. 2012). Debates about Pacific voyaging are perennial. Fifty years ago Andrew Sharp (1957, 1963) was sceptical about the ability of traditional navigators to find their way at sea and, more especially, to find their way back over long distances with sailing directions for others to follow. -

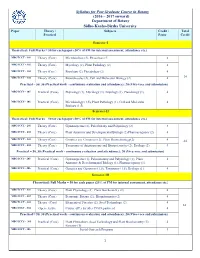

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 Onward)

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 onward) Department of Botany Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University Paper Theory / Subjects Credit / Total Practical Paper Credit Semester-I Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 101 Theory (Core) Microbiology (2), Phycology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 102 Theory (Core) Mycology (2), Plant Pathology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 103 Theory (Core) Bryology (2), Pteridology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 104 Theory (Core) Biomolecules (2), Cell and Molecular Biology (2) 4 24 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 105 Practical (Core) Phycology (1), Mycology (1), Bryology (1), Pteridology (1). 4 MBOTCCS - 106 Practical (Core) Microbiology (1.5), Plant Pathology (1), Cell and Molecular 4 Biology (1.5). Semester-II Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 201 Theory (Core) Gymnosperms (2), Paleobotany and Palynology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 202 Theory (Core) Plant Anatomy and Developmental Biology (2) Pharmacognosy (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 203 Theory (Core) Genetics and Genomics (2), Plant Biotechnology(2) 4 24 MBOTCCT - 204 Theory (Core) Taxonomy of Angiosperms and Biosystematics (2), Ecology (2) 4 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 205 Practical (Core) Gymnosperms (1), Palaeobotany and Palynology (1), Plant 4 Anatomy & Developmental Biology (1), Pharmacognosy (1). MBOTCCS - 206 Practical (Core) Genetics and Genomics (1.5), Taxonomy (1.5), Ecology (1). 4 Semester-III Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 301 Theory (Core) Plant Physiology (2), Plant Biochemistry (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 302 Theory (Core) Economic Botany (2), Bioinformatics (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 303 Theory (Core) Elements of Forestry (2), Seed Technology (2). -

Multipurpose Trees for Agroforestry in the Pacific Islands

For Educators, Gardeners, Farmers, Foresters, and Landscapers Agroforestry Guides for Pacific Islands “Well-researched, concise, user-friendly...an invaluable practical resource for those working to conserve and expand the use of trees in agricultural systems.” —APANews, The Asia-Pacific Agroforestry Newsletter FAO Regional Office, Bangkok, Thailand “A significant contribution to public education, advancing the cause of integrated agriculture and forestry...a resource of lasting value.” —The Permaculture Activist, North Carolina “A most excellent handbook...a wonderful resource.” —Developing Countries Farm Radio Network, Toronto, Canada “Eloquently makes a case for reintroducing and emphasizing trees in our island agriculture.” —Dr. Bill Raynor, Program Director, The Nature Conservancy, Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia “Provides a real clearinghouse on traditional and modern agroforestry not only for Pacific Islands, also very useful for other regions.” —ILEIA Newsletter for Low External Input and Sustainable Agriculture, The Netherlands Purchase the book at http://www.agroforestry.net/afg/ Agroforestry Guides for Pacific Islands edited by Craig R. Elevitch and Kim M. Wilkinson Price: $24.95 (plus shipping) Availability: Usually ships within one business day. Paperback - 240 pages, illustrated and fully indexed Release date: September, 2000 ISBN: 0970254407 Publisher: Permanent Agriculture Resources, P.O. Box 428, Holualoa, HI, 96725, USA. Tel: 808-324-4427, Fax: 808-324-4129, email: [email protected] Agroforestry Guides for Pacific Islands #2 Multipurpose Trees for Agroforestry in the Pacific Islands by Randolph R. Thaman, Craig R. Elevitch, and Kim M. Wilkinson www.agroforestry.net Multipurpose Trees for Agroforestry in the Pacific Islands Abstract: The protection and planting of trees in agroforestry systems can serve as an important, locally achievable, and cost-effective step in sustainable development in the Pacific Islands.