3.2.6. Methods for Field Measurement and Remote Sensing of the Swash Zone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Field Experiment on a Nourished Beach

CHAPTER 157 A Field Experiment on a Nourished Beach A.J. Fernandez* G. Gomez Pina * G. Cuena* J.L. Ramirez* Abstract The performance of a beach nourishment at" Playa de Castilla" (Huel- va, Spain) is evaluated by means of accurate beach profile surveys, vi- sual breaking wave information, buoy-measured wave data and sediment samples. The shoreline recession at the nourished beach due to "profile equilibration" and "spreading out" losses is discussed. The modified equi- librium profile curve proposed by Larson (1991) is shown to accurately describe the profiles with a grain size varying across-shore. The "spread- ing out" losses measured at " Playa de Castilla" are found to be less than predicted by spreading out formulations. The utilization of borrowed material substantially coarser than the native material is suggested as an explanation. 1 INTRODUCTION Fernandez et al. (1990) presented a case study of a sand bypass project at "Playa de Castilla" (Huelva, Spain) and the corresponding monitoring project, that was going to be undertaken. The Beach Nourishment Monitoring Project at the "Playa de Castilla" was begun over two years ago. The project is being *Direcci6n General de Costas. M.O.P.T, Madrid (Spain) 2043 2044 COASTAL ENGINEERING 1992 carried out to evaluate the performance of a beach fill and to establish effective strategies of coastal management and represents one of the most comprehensive monitoring projects that has been undertaken in Spain. This paper summa- rizes and discusses the data set for wave climate, beach profiles and sediment samples. 2 STUDY SITE & MONITORING PROGRAM Playa de Castilla, Fig. 1, is a sandy beach located on the South-West coast of Spain between the Guadiana and Gualdalquivir rivers. -

USER MANUAL SWASH Version 7.01

SWASH USER MANUAL SWASH version 7.01 SWASH USER MANUAL by : TheSWASHteam mail address : Delft University of Technology Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences Environmental Fluid Mechanics Section P.O. Box 5048 2600 GA Delft The Netherlands website : http://www.tudelft.nl/swash Copyright (c) 2010-2020 Delft University of Technology. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back- Cover Texts. A copy of the license is available at http://www.gnu.org/licenses/fdl.html#TOC1. iv Contents 1 About this manual 1 2 Generaldescriptionandinstructionsforuse 3 2.1 Introduction................................... 3 2.2 Background,featuresandapplications . ...... 3 2.2.1 Objectiveandcontext ......................... 3 2.2.2 Abird’s-eyeviewofSWASH. 4 2.2.3 ModelfeaturesandvalidityofSWASH . 7 2.2.4 Relation to Boussinesq-type wave models . .... 8 2.2.5 Relation to circulation and coastal flow models. ...... 9 2.3 Internal scenarios, shortcomings and coding bugs . ......... 9 2.4 Unitsandcoordinatesystems . 10 2.5 Choiceofgridsandtimewindows . .. 11 2.5.1 Introduction............................... 11 2.5.2 Computationalgridandtimewindow . 12 2.5.3 Inputgrid(s)andtimewindow(s) . 13 2.5.4 Input grid(s) for transport of constituents . ...... 14 2.5.5 Outputgrids .............................. 15 2.6 Boundaryconditions .............................. 16 2.7 Timeanddatenotation ............................ 17 2.8 Troubleshooting................................. 17 3 Input and output files 19 3.1 General ..................................... 19 3.2 Input/outputfacilities . .. 19 3.3 Printfileanderrormessages . .. 20 4 Description of commands 21 4.1 Listofavailablecommands. -

Coastal Landform Processes 29/03/2018 Do Now Copy Below: When Waves Lose Energy Material Is Deposited

Coastal Landform Processes 29/03/2018 Do Now Copy below: When waves lose energy material is deposited. This typical happens in sheltered areas such as bays, this explains why beaches are found here. Wave refraction is where the energy of the wave is reduced Aim ▪ To understand process acting on the coast that lead to landforms Wave energy converges on the headlands Wave energy is diverged Wave energy converges on the headlands Sediment moves and is deposited http://www.bbc.co.uk/education/cli ps/zsmb4wx Erosion Destructive waves will erode the coastline in four different ways: 1. Hydraulic Power Complete your 2. Corrasion erosion sheet 3. Attrition 4. Corrosion 5. Abrasion Longshore Drift • “Longshore drift is a process by which sediments such as sand or other materials are transported along a beach.” • The general direction of longshore drift around the coasts of the British Isles is controlled by the direction of the dominant wind. http://www.bbc.co.uk/learningzo ne/clips/the-coastline- longshore-drift-and- spits/3086.html Longshore Drift: A bird’s eye view Cliff Beach Sea Longshore Drift: A bird’s eye view Cliff Eroded material Beach from the cliffs is left on the beach Bob the pebble Sea Longshore Drift: A bird’s eye view Cliff Beach Waves The waves from the sea come onto the beach at an angle and pick Bob and other material up and move them up the beach. Sea Longshore Drift: A bird’s eye view Cliff Beach Swash This movement of the waves is called SWASH. The waves come in at an angle due to Sea wind direction Longshore Drift: A bird’s eye view Cliff Beach The waves then move back down the beach in a straight Swash direction due to gravity. -

Under Pressure Coastal Stack & Stump: Sediment Are Thrown Against Weathering (Freeze- the Cliffs by Waves

Tides: UP1 –Waves & Tides Constructive Waves: Longshore Drift: Transportation: • These are the rise and fall of the sea level, due • Traction: mainly to the pull of the moon • Strong swash and weak backwash that • Waves approach the beach at an angle due Large boulders and sediments • As the moon travels around the Earth, it push sand and pebbles up the beach to the prevailing wind direction are rolled along the sea bed. attracts the sea and pulls it upwards. The sun • Low waves with longer gaps between the • As the wave breaks, the swash carries They are too heavy to be helps too – but its much further away. So its crests (6-8 per min – low frequency) material up the beach at the same angle pull is not as strong. • Under 1m (oblique angle) as the prevailing wind picked up fully by the waves. • High tide occurs about every 12 and ½ hours, • Known as spilling waves as they ‘spill’ up • The backwash carries material back down with low tides in between. The difference the beach the beach at a right angle (90o) due to • Saltation: between the high and low tide is called the tidal • Gently sloping wave front gravity where small pieces of shingle range • Formed by storms often 100s KMs away • This means that material is moved along the or large sand grains are • Gentle beach beach in a zig zag route bounced along the sea bed. Waves: Destructive Waves: • Suspension: • Are formed by wind that blows over the sea, friction with the surface of water causes • Weak swash and strong backwash pulling small particles such as silts ripples to form and these develop into waves. -

Turbulence in the Swash and Surf Zones: a Review

Coastal Engineering 45 (2002) 129–147 www.elsevier.com/locate/coastaleng Turbulence in the swash and surf zones: a review Sandro Longo a,*, Marco Petti b,1, Inigo J. Losada c,2 aDepartment of Civil Engineering, University of Parma, Parco Area delle Scienze, 181/A, 43100 Parma, Italy bDipartimento di Georisorse e Territorio, Faculty of Engineering, University of Udine, Via del Cotonificio, 114, 33100 Udine, Italy cOcean and Coastal Research Group, Universidad de Cantabria, E.T.S.I.C.C. y P. Av. de los Castros s/n, 39005 Santander, Spain Abstract This paper reviews mainly conceptual models and experimental work, in the field and in the laboratory, dedicated during the last decades to studying turbulence of breaking waves and bores moving in very shallow water and in the swash zone. The phenomena associated with vorticity and turbulence structures measured are summarised, including the measurement techniques and the laboratory generation of breaking waves or of flow fields sharing several characteristics with breaking waves. The effect of air entrapment during breaking is discussed. The limits of the present knowledge, especially in modelling a two- or three-phase system, with air and sediment entrapped at high turbulence level, and perspectives of future research are discussed. D 2002 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Swash zone; Surf zone; Breaking waves; Turbulence; Length scales; Coastal hydrodynamics 1. Introduction short and long waves, currents, turbulence and vorti- ces may be present. Therefore, the hydrodynamics to The swash zone is defined as the part of the beach be found in the swash zone is largely determined by between the minimum and maximum water levels the boundary conditions imposed by the beach face during wave runup and rundown. -

National List of Beaches 2008

National List of Beaches September 2008 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington DC 20460 EPA-823-R-08-004 Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 States Alabama........................................................................................................................................... 3 Alaska .............................................................................................................................................. 5 California.......................................................................................................................................... 6 Connecticut .................................................................................................................................... 15 Delaware........................................................................................................................................ 17 Florida ............................................................................................................................................ 18 Georgia .......................................................................................................................................... 31 Hawaii ............................................................................................................................................ 33 Illinois ............................................................................................................................................ -

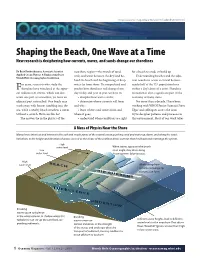

Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New Research Is Deciphering How Currents, Waves, and Sands Change Our Shorelines

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v43n1/raubenheimer.html Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New research is deciphering how currents, waves, and sands change our shorelines By Britt Raubenheimer, Associate Scientist nearshore region—the stretch of sand, for a beach to erode or build up. Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Dept. rock, and water between the dry land be- Understanding beaches and the adja- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hind the beach and the beginning of deep cent nearshore ocean is critical because or years, scientists who study the water far from shore. To comprehend and nearly half of the U.S. population lives Fshoreline have wondered at the appar- predict how shorelines will change from within a day’s drive of a coast. Shoreline ent fickleness of storms, which can dev- day to day and year to year, we have to: recreation is also a significant part of the astate one part of a coastline, yet leave an • decipher how waves evolve; economy of many states. adjacent part untouched. One beach may • determine where currents will form For more than a decade, I have been wash away, with houses tumbling into the and why; working with WHOI Senior Scientist Steve sea, while a nearby beach weathers a storm • learn where sand comes from and Elgar and colleagues across the coun- without a scratch. How can this be? where it goes; try to decipher patterns and processes in The answers lie in the physics of the • understand when conditions are right this environment. Most of our work takes A Mess of Physics Near the Shore Many forces intersect and interact in the surf and swash zones of the coastal ocean, pushing sand and water up, down, and along the coast. -

Effects of Porous Mesh Groynes on Macroinvertebrates of a Sandy Beach, Santa Rosa Island, Florida, U.S.A

Gulf of Mexico Science Volume 26 Article 4 Number 1 Number 1 2008 Effects of Porous Mesh Groynes on Macroinvertebrates of a Sandy Beach, Santa Rosa Island, Florida, U.S.A. W.J. Keller University of West Florida C.M. Pomory University of West Florida DOI: 10.18785/goms.2601.04 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/goms Recommended Citation Keller, W. and C. Pomory. 2008. Effects of Porous Mesh Groynes on Macroinvertebrates of a Sandy Beach, Santa Rosa Island, Florida, U.S.A.. Gulf of Mexico Science 26 (1). Retrieved from https://aquila.usm.edu/goms/vol26/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf of Mexico Science by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Keller and Pomory: Effects of Porous Mesh Groynes on Macroinvertebrates of a Sandy B Gv.ljofMexiw Sdcnct, 2008(1), pp. 36-45 Effects of Porous Mesh Groynes on Macroinvertebrates of a Sandy Beach, Santa Rosa Island, Florida, U.S.A. W . .J. KELLER iu'ID C. M. POMORY The use of porous mesh groynes to accrete sand and stop erosion is a relath·ely new method of beach nourishment. Five groyne, five intergroync, and five control transects outside the groyne area on a beach near Destin, FL were santpled during the initial 3 mo after installment of groynes for Arenicola crista/a (polychaete) burrow numbers, benthic macroinvertcbrate numbers, and dry mass. -

Chapter 43 Turbulence Scales in the Surf And

CHAPTER 43 TURBULENCE SCALES IN THE SURF AND SWASH Reinhard E. Flick California Department of Boating and Waterways and Ronald A. George Center for Coastal Studies-0209 Scripps Institution of Oceanography La Jolla, California, USA 92093-0209 Abstract Ocean surface gravity waves breaking on gently sloping beaches generate sub- stantial turbulent velocity fluctuations, both from overturning at the surface bore and from shear stresses at the bottom. We have used measurements made with laboratory-style hotfilm anemometers in the surf and swash on a natural beach to determine the relevant length and velocity scales. Battjes (1975) has pointed out the importance of determining the turbulence scales in the surf zone. Modelers, such as Svendsen and Madsen (1984), for example, rely on length and velocity scale esti- mates to parameterize and solve the complicated equations that govern surf zone flows. We find that turbulence length scales depend essentially on the bore height, and therefore on the local depth, but may decrease sharply under the bore. We also determine that at least the horizontal velocities approach isotropy at frequencies of 2 to 3 Hz, which turn out to also correspond to length scales on the order of the local depth. Introduction The determination of "scales" plays an important role in turbulence research, since turbulent flows must be described by their characteristic times, lengths, veloci- ties, kinetic energies, Reynolds stresses, eddy viscosities and dissipation rates. Much of the theory of turbulence is concerned with establishing connections and relationships between these parameters and much experimental effort has gone into guiding these concerns. The basic reason why this approach is necessary, is that tur- bulent flows typically contain velocity fluctuations at a broad range of length scales, particularly small ones, so that direct analytical or numerical solution of the govern- ing equations is unmanageable. -

Laurentian Great Lakes, Interaction of Coastal and Offshore Waters Introduction

1Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series IEncyclopedia of Lakes and Reservoirs ISpringer Science+Business Media B.V. 2012 110.1007/978-1-4020-4410-6_264 ILars Bengtsson, Reginald W. Herschyand Rhodes W. Fairbridge Laurentian Great Lakes, Interaction of Coastal and Offshore Waters 1 21S3 Yerubandi R. Rao IS3 and David J. Schwab (1) Environment Canada, National Water Research Institute, Canada Center for Inland Waters, 867 Lakeshore Road, Burlington, ON, Canada (2) Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, 2205 Commonwealth Blvd, Ann Arbor, MI 48105, USA IS::l Yerubandi R. Rao (Corresponding author) Email: [email protected] [;] David J. Schwab Email: [email protected] Without Abstract Introduction The Laurentian Great Lakes represent an extensive, interconnected aquatic system dominated by its coastal nature. While the lakes are large enough to be significantly influenced by the earth's rotation, they are at the same time closed basins to be strongly influenced by coastal processes (Csanady, 1984). Nowhere is an understanding of how physical, geological, chemical, and biological processes interact in a coastal system more important to a body of water than the Great Lakes. Several factors combine to create complex hydrodynamics in coastal systems, and the associated physical transport and dispersal processes of the resulting coastal flow field are equally complex. Physical transport processes are often the dominant factor in mediating geochemical and biological processes in the coastal environment. Thus, it is critically important to have a thorough understanding of the coastal physical processes responsible for the distribution of chemical and biological species in this zone. However, the coastal regions are not isolated but are coupled with mid-lake waters by exchanges involving transport of materials, momentum, and energy. -

Wave Runup on Atoll Reefs

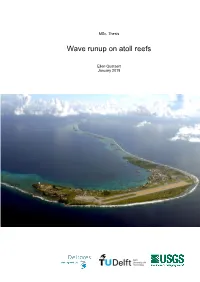

MSc. Thesis Wave runup on atoll reefs Ellen Quataert January 2015 Front cover: Aerial view of the southern tip of the Kwajalein Atoll in the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Source: www.fayeandsteve.com Wave runup on atoll reefs Ellen Quataert 1210070-000 © Deltares, 2015, B Keywords Runup, atoll reef, XBeach, infragravity wave, wave-induced setup, incident swash, infragravity swash, Kwajalein Summary The aim of this research was to take the first step in understanding the wave runup process on an atoll reef using the XBeach model. Field data collected from 3 November 2013 to 13 April 2014 at Kwajalein Atoll in the Republic of the Marshall Islands was used. The dataset included data on bathymetry, waves, water levels and wave-induced runup. The data was analysed and subsequently used to model the hydrodynamics across the reef and the wave runup. The hydrostatic and non-hydrostatic XBeach models were used to capture both components of runup, infragravity and incident swash. Finally, a conceptual model was created to investigate the effect of variations in the atoll reef parameter space on the wave runup. References 1210070-000 Version Date Author Initials Review Initials Approval Initials Jan. 2015 E. Quataert A.R. van Dongeren F. Hoozemans A.A. van Rooijen State final Wave runup on atoll reefs Wave runup on atoll reefs by Ellen Quataert in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Civil Engineering Delft University of Technology January 2015 In collaboration with: Graduation committee: Prof. dr. ir. M.J.F. Stive Delft University of Technology ir. -

Connecting Wind-Driven Upwelling and Offshore Stratification To

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by DigitalCommons@CalPoly PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans RESEARCH ARTICLE Connecting wind-driven upwelling and offshore stratification 10.1002/2014JC009998 to nearshore internal bores and oxygen variability 1 2 3 1 Key Points: Ryan K. Walter , C. Brock Woodson , Paul R. Leary , and Stephen G. Monismith • Regional upwelling and relaxation 1 2 cycles modulate offshore Environmental Fluid Mechanics Laboratory, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA, COBIA Lab, College of stratification 3 Engineering, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA, Hopkins Marine Station, Stanford University, Pacific Grove, • Changes in offshore stratification California, USA modify the nearshore internal bore field • Upwelling regimes and bores are important for assessing oxygen Abstract This study utilizes field observations in southern Monterey Bay, CA, to examine how regional- variability scale upwelling and changing offshore (shelf) conditions influence nearshore internal bores. We show that the low-frequency wind forcing (e.g., upwelling/relaxation time scales) modifies the offshore stratification Correspondence to: and thermocline depth. This in turn alters the strength and structure of observed internal bores in the near- R. K. Walter, [email protected] shore. An internal bore strength index is defined using the high-pass filtered potential energy density anomaly in the nearshore. During weak upwelling favorable conditions and wind relaxations, the offshore Citation: thermocline deepens. In this case, both the amplitude of the offshore internal tide and the strength of the Walter, R. K., C. B. Woodson, P. R. Leary, nearshore internal bores increase. In contrast, during strong upwelling conditions, the offshore thermocline and S.