Opening the Door on Charles Sturt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2014-2015

SOUTH AUSTRALIA _____________________ THIRTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE HISTORY TRUST of SOUTH AUSTRALIA D (History SA) FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2015 History SA Directorate Torrens Parade Ground Victoria Drive Adelaide SA 5000 GPO Box 1836 Adelaide SA 5001 DX 464 Adelaide Telephone: +61 8 8203 9888 Facsimile: +61 8 8203 9889 Email: [email protected] Websites: History SA: www.history.sa.gov.au Migration Museum: www.migration.history.sa.gov.au National Motor Museum: www.motor.history.sa.gov.au South Australian Community History: www.community.history.sa.gov.au South Australian Maritime Museum: www.maritime.history.sa.gov.au Adelaidia: www.adelaidia.sa.gov.au About Time: South Australia’s History Festival: www.abouttime.sa.gov.au A World Away: www.southaustraliaswar.com.au Bound for South Australia: www.boundforsouthaustralia.com.au History as it Happens www.historyasithappens.com.au SA History Hub: www.sahistoryhub.com.au This report is prepared by the Directorate of History SA ABN 17 521 345 493 ISSN 1832 8482 ISBN 978 0 646 91029 1 CONTENTS LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL ................................................................................................................ 1 BACKGROUND......................................................................................................................................... 2 ROLE AND PRINCIPAL OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................... 2 VISION ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Journal of the Australian Naval Institute

VOLUME 10 AUGUST 1984 NUMBER 3 JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL INSTITUTE Registered by Australian Post Publication No. NBP 0282 AUSTRALIAN NAVAL INSTITUTE 1. The Australian Naval Institute is incorporated in the Australian Capital Territory. The main objects of the Institute are: a. to encourage and promote the advancement of knowledge related to the Navy and the maritime profession, b. to provide a forurn for the exchange of ideas concerning subjects related to the Navy and the maritime profess on, and c. to publish a journal. 2. The Institute is self supporting and non-profit making The aim is to encourage discussion, dis- semination of information, comment and opinion and the advancement of professional knowledge concerning naval and maritime matters. 3. Membership of the Institute is open to — a. Regular Members - Members of the Permanent Naval Forces of Australia, b Associate Members -(1) Members of the Reserve Naval Forces of Australia. (2) Members of the Australian Military Forces and the Royal Australian Air Force both permanent and reserve. (3) Ex-members of the Australian Defence Force, both permanent and reserve components, provided that they have been honourably discharged from that Force. (4) Other persons having and professing a special interest in naval and maritime affairs. c. Honorary Members - Persons who have made distinguished contributions to the naval or maritime profession or who have rendered distinguished service to the Institute may be elected by the Council to Honorary Membership. 4 Joining fee for Regular and Associate members is $5. Annual subscription for both is $15. 5. Inquiries and application for membership should be directed to: The Secretary, Australian Naval Institute, PO Box 80 CAMPBELL ACT 2601 CONTRIBUTIONS In order to achieve the stated aims of the Institute, all readers, both members and non-members, are encouraged to submit articles for publication. -

'We Were Going to Be Different'

‘We were going to be different’ The story of The Kosmopolitan Klub and The Girls Anne Rawson The story, in their own words, of a group of girls who grew up by the beach in Adelaide, who formed the Kosmopolitan Klub (colours: orange and green), gave themselves extraordinary names, produced a magazine, held dances, went on holiday, got married and stayed friends all their lives. © Anne Rawson First published in Canberra in 1998 ISBN 0 9585733 5 2 Second edition as an e-book in 2018 Anne Rawson Mobile: +61 408 879 224 Phone: +61 2 62543894 email: [email protected] In memory of my mother the Lady Camelia Featherstonehaugh my aunt the Czarina Nadja Zamoyski and all my honorary aunts Contents Introduction ...........................................................1 List of names ...................................................... 11 Maps ...................................................................12 First and last meetings .......................................14 Beginnings ..........................................................20 The Tech .............................................................32 Working in the depression ..................................50 The Kosmopolitan Klub ......................................66 My Grandmother.................................................85 The Kosmopolitan Kourier ..................................88 The boys and the men ...................................... 112 The war years ...................................................138 The Girls ...........................................................152 -

History of Trade in South Australia

History of Trade in South Australia Trade has been happening in South Australia for thousands of years. There have been many changes to the way we trade and exchange goods, and the types of goods that are traded. Advances in technology and the needs of people have driven these changes. The Aboriginal people traded goods amongst themselves and indigenous groups long before European people arrived, and it was vital to their existence. Food was not traded over large distances, but other highly valued and scarce resources were traded. Stones, ochres, tools, ceremonial items and other resources that were not normally available within one area could be obtained through trade from another area. Trade was also seen as a form of social control and law, as it required people from different areas and different groups to respect each other’s rights, boundaries and cultural differences. It helped strengthen relationships between neighbouring Aboriginal groups by providing an opportunity to settle disputes, meet to discuss laws and for sharing gifts of respect. In 1836, nine ships arrived in South Australia bringing 546 European people to this state. The European people lived very different lifestyles to the Aboriginal people, their needs and wants were very different, and changed the ways and types of products that were brought into our state. In the early days of European settlement, ships would come in to the harbour and unload cargo the best that they could. At this time, all goods were imported, with no exports. The harbour was rough and very disorganised and anyone could load / unload cargo along the beaches. -

Tourism Strategy & Action Plan

TOURISM STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN 2020 1 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................................................4 CITY PLAN 2030 ......................................................................................................................................................6 2020 STRATEGIC OUTCOMES AND ACTIONS ............................................................................................8 Snapshot of Key experiences and Hero products ...................................................................................... 12 TOURISM ACTION PLAN .................................................................................................................................. 14 Measurement of Key Performance Indicators ............................................................................................. 24 2 WELCOME MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR The City of Port Adelaide Enfield has some of the most unique tourism offerings in South Australia, which we are proud to showcase to the world. We also have a strong awareness and recognition of local Aboriginal “Kaurna” Culture. We have everything from the natural beauty of our pristine beaches, Linear Park, our world famous Port River dolphins, through to the historic museum precinct and buildings of Port Adelaide. We are also becoming a destination for “foodies” with Prospect Road in the eastern side of the Council region, Semaphore Road and Commercial Road North in Port Adelaide all -

City of Port Adelaide Enfield Heritage Review

CITY OF PORT ADELAIDE ENFIELD HERITAGE REVIEW MARCH 2014 McDougall & Vines Conservation and Heritage Consultants 27 Sydenham Road, Norwood, South Australia 5067 Ph (08) 8362 6399 Fax (08) 8363 0121 Email: [email protected] PORT ADELAIDE ENFIELD HERITAGE REVIEW CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objectives of Review 1.2 Stage 1 & 2 Outcomes 2.0 NARRATIVE THEMATIC HISTORY - THEMES & SUB-THEMES 3 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Chronological History of Land Division and Settlement Patterns 2.2.1 Introduction 2.2.2 Land Use to 1850 - the Old and New Ports 2.2.3 1851-1870 - Farms and Villages 2.2.4 1870-1885 - Consolidation of Settlement 2.2.5 1885-1914 - Continuing Land Division 2.2.6 1915-1927 - War and Town Planning 2.2.7 1928-1945 - Depression and Industrialisation 2.2.8 1946-1979 - Post War Development 2.3 Historic Themes 18 Theme 1: Creating Port Adelaide Enfield's Physical Environment and Context T1.1 Natural Environment T1.2 Settlement Patterns Theme 2: Governing Port Adelaide Enfield T2.1 Levels of Government T2.2 Port Governance T2.3 Law and Order T2.4 Defence T2.5 Fire Protection T2.6 Utilities Theme 3: Establishing Port Adelaide Enfield's State-Based Institutions Theme 4: Living in Port Adelaide Enfield T4.1 Housing the Community T4.2 Development of Domestic Architecture in Port Adelaide Enfield Theme 5: Building Port Adelaide Enfield's Commercial Base 33 T5.1 Port Activities T5.2 Retail Facilities T5.3 Financial Services T5.4 Hotels T5.5 Other Commercial Enterprises Theme 6: Developing Port Adelaide Enfield's Agricultural -

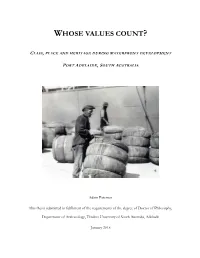

Whose Values Count?

WHOSE VALUES COUNT? CLASS, PLACE AND HERITAGE DURING WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT PORT ADELAIDE, SOUTH AUSTRALIA Adam Paterson This thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Archaeology, Flinders University of South Australia, Adelaide January 2015 Abstract In Australia there has been little critical reflection on the role that class plays during negotiations over cultural heritage. This stands in contrast to the United Kingdom and the United States, where research aiming to develop a better understanding of how class shapes cultural heritage practice is more common. Key research themes in these countries include identifying how working-class people participate in cultural heritage activities; determining what barriers exist to their participation and what social purpose cultural heritage has within post-industrial communities; and understanding how cultural heritage is used in negotiations over the classed meanings of place during gentrification. This thesis explores the relationships between class, place and heritage in Port Adelaide, South Australia. Once a prosperous industrial and commercial port, since the 1980s Port Adelaide has undergone slow social and economic change. In 2002, the State Government announced plans for major re-development of surplus waterfront land in order to generate profit and economic stimulation for the Port through extensive and rapid development, radically transforming Port Adelaide physically and socially. Drawing on a theoretical framework that -

Walk20the20port202013.Pdf

rive Road Commercial and Street Nile of corner on Sign astal D ic Co Scen Tel: 8405 6560 or Email: [email protected] Email: or 6560 8405 Tel: on Centre Information Visitor Adelaide Port the contact - essential Bookings 16 permitting) (weather 17 Thursday & Sunday every 2pm at Offered Port Walks - let a local be your guide your be local a let - Walks Port 15 Walks Guided 20 19 13 21 18 www.environment.sa.gov.au/heritage Website: 8 Australia South of Areas Heritage State 14 Wauwa st Dept for Environment, Water and Natural Resources Natural and Water Environment, for Dept 7 23 27 24 22 25 6 9 exhibition permanent Adelaide Port of History 12 day) Christmas (closed 5pm to 10am from Daily Open: 42 26 11 32 5 10 28 1 Adelaide Port 4 Street Lipson 126 31 3 34 33 South Australian Maritime Museum Maritime Australian South 2 41 29 30 2-5pm 39 Friday 2-5pm 35 Thursday 10am-1pm Wednesday rive 40 Coastal D 36 Researchers for Open Scenic 6580 8405 Tel: Port Adelaide Port Street Church 2 Library Adelaide Port 38 Room History Local Port Adelaide visit: Adelaide Port historic about more out find To 37 Adelaide Port Historic Map Legend Port Adelaide Port Adelaide Walk The Port Port Adelaide is a sea port city with a How to get there… Heritage Walking Tour of Port Adelaide unique, salty tang to its environs. 1 Port Adelaide Visitor Information Centre, ◆ 15 Dockside Tavern, c1898 29 Nile Street Power Station - 1860 Footpath Plaque It is the historic maritime heart of South Australia and home to some of the finest 16 SS Admella Memorial - The Navigator historic buildings in the State. -

Historic Ships and Boats Strategy

Prepared by Mulloway Studio for Renewal SA RESA04 _ FINAL PORT ADELAIDE RENEWAL PROJECT Historic ships a n d boats strategy R e p o r t Table of contents Section Page 1 01.00 Introduction 01.01 Approach and Methodology Page 3 02.00 Stakeholders Page 6 03.00 Ships and boats 03.00 Current ships location 03.01 One And All.Mission Statement 03.02 One And All 03.03 Falie.Mission Statement 03.04 Falie 03.05 City of Adelaide Clipper Ship.V ision 03.06 City of Adelaide Clipper Ship 03.07 Fearless.A rchie Badenoch.Y elta.N elcebee Mission Statement 03.08 Yelta 03.09 Archie Badenoch 03.10 Fearless 03.11 Nelcebee RESA04 _ FINAL Table of contents Section Page 19 04.00 Site Analysis 04.01 Pe destrian access 04.02 Vehicle access 04.03 Zone activity 04.04 View 04.05 Site summary 04.06 Fletcher’s Slip 04.07 Shed 26 04.08 Hart’s Mill 04.09 Cruickshank’s Corner 04.10 Dock 2 Page 30 05.00 General Guiding Principles 05.01 Siting Opportunities and Recommendations 05.02 Option: Location 05.03 Option: City of Adelaide 05.04 Option: South Australian Maritime Museum 05.05 Option: Combined 05.06 Conclusion 05.07 Cost: Notes Page 49 06.00 Implementation Page 53 07.00 Appendices 07.00 Appendix A.City of Adelaide Clipper Ship 07.01 Appendix B.SAMM RESA04 _ FINAL Document control Issue Issue date Revision notes Draft 01 15th November 2016 ships and boats strategy _ draft 1 _ 15 November 2016 _ RM comments.pdf Draft 02 23r d November 2016 ships and boats strategy _ draft 2 _ 23 november 2016 _ track changes.pdf Draft 03 28th November 2016 Draft 04 9th December 2016 Draft 05 14th December 2016 Draft 06 02nd March 2017 Draft 07 14th March 2017 Final 15th March 2017 RESA04 _ FINAL Port Adelaide Renewal Project Introduction 1 01.00 Introduction As part of the Port Renewal Project, Mulloway Studio was engaged by the Urban Renewal Authority (Renewal SA) to undertake a strategy for berthing or locating historic ships and vessels within the inner harbour of Port Adelaide. -

South Australian Heritage Register

South Australian HERITAGE COUNCIL South Australian Heritage Register List of State Heritage Places in South Australia – as at 2 February 2021 SH FILE NO DATE LISTED STATE HERITAGE PLACE ADDRESS LOCAL COUNCIL AREA 10321 8/11/1984 Goodlife Health Club (former Bank of Adelaide Head Office) 81 King William Street, ADELAIDE Adelaide 10411 11/12/1997 Shops (former Balfour's Shop and Cafe) 74 Rundle Mall, ADELAIDE Adelaide 10479 8/11/1984 Divett Mews (former Goode, Durrant & Co. Stables) Divett Place, ADELAIDE Adelaide 10480 8/11/1984 Cathedral Hotel Kermode Street, NORTH ADELAIDE Adelaide 10629 5/04/1984 Dwelling ('Admaston', originally 'Strelda') 219 Stanley Street, NORTH ADELAIDE Adelaide 1‐Mar Finniss Street and MacKinnon 10634 5/04/1984 Shop & Dwellings Parade, NORTH ADELAIDE Adelaide 10642 23/09/1982 Museum of Economic Botany, Adelaide Botanic Garden Park Lands, ADELAIDE Adelaide 10643 23/09/1982 Barr Smith Library (original building only), The University of Adelaide North Terrace, ADELAIDE Adelaide 10654 6/05/1982 Old Methodist Meeting Hall 25 Pirie Street, ADELAIDE Adelaide Pennington Terrace, NORTH 10756 24/07/1980 Walkley Cottage (originally Henry Watson's House), St Mark's College [modified 'Manning' House] ADELAIDE Adelaide 10760 26/11/1981 House ‐ 'Dimora', front fence and gates and southern boundary wall 120 East Terrace, ADELAIDE Adelaide 10761 28/05/1981 Former Centre for Performing Arts (former Teachers Training School), including Northern and Western Boundary Walls Grote Street, ADELAIDE Adelaide 10762 24/07/1980 Adelaide Remand -

Open Space Strategy 2021-2026

OPEN SPACE STR ATEGY 2021-2026 September 2020 Table of Contents 1. Our context 2 2. Strategic Outcomes 8 2.1 Equitable Provision and Changing Urban Form 10 2.2 Natural Systems, Environment and Climate Change 14 2.3 Sport Facility Provision 18 2.4 Recreation, Health and Wellbeing 22 2.5 Destinations, Culture and Art 26 2.6 Improve Decision Making 30 3. The Action Plan 34 The Actions for Coast North 36 The Actions for Coast South 38 The Actions for The Port 40 The Actions for The Parks 42 The Actions for The Inner 44 The Actions for The East North 46 The Actions for The East South 48 Keep Informed 51 OPEN SPACE STRATEGY 2021-2026 The City of PAE is a unique ensuring that there is a large amount urban environment and located of good quality open space across the in a region that provides close PAE region for our diverse and growing connections between residential population. living, a prosperous commercial and industrial sector and a This strategy provides the framework natural environment for outdoor for the way we plan, develop and provide activities and nature-based these open spaces for our community. tourism destinations. Our aim is to ensure that everyone in We have a rich maritime history and a our community has access to open spaces vibrant arts and cultural ecology. We and sporting and recreational facilities to Claire Boan are proud of our Aboriginal heritage and support health and wellbeing, play, leisure local Kaurna culture, and acknowledge and social inclusion. Mayor and value the significant contribution made by Aboriginal people to our City We have identified our key challenges through their maintenance and sharing of for the short and long term, and culture and connection to country. -

Essence of Heritage Photo / Video Competition

The South Australian Heritage Council and Heritage South Australia present… ESSENCE OF HERITAGE PHOTO / VIDEO COMPETITION The finalists of 2019 Special thanks to our sponsors: MAPLAND 1. CARRICK HILL FULLARTON ROAD, SPRINGFIELD PHOTO BY ANTHONY ANDERSON STATE HERITAGE PLACE – No. 11509 Carrick Hill is significant as the home of prominent South Australian businessman and philanthropist, Sir Edward Hayward and Ursula Hayward, renowned art collector. Also significant is that much of the interior furnishings dates back to the sixteenth century, in addition to holding world-recognised works of art and priceless antiques. Carrick Hill is important because the grand mansion, set amidst a large park, establishes and continues the estate and park like tradition of Springfield. Heritage South Australia Department for Environment and Water P (08) 8124 4960 E [email protected] www.environment.sa.gov.au/topics/heritage 2. BIRKENHEAD BRIDGE, PORT ADELAIDE PHOTO BY ROBYN ASHWORTH STATE HERITAGE PLACE – No. 14348 The Birkenhead Bridge across the Gawler Reach of the Port River was completed in 1940. It is significant for being Australia's first double bascule bridge. The only other opening bridge remaining in South Australia (in 1999) is the vertical lift span bridge at Paringa on the River Murray. Heritage South Australia Department for Environment and Water P (08) 8124 4960 E [email protected] www.environment.sa.gov.au/topics/heritage 3. ANGASTON WAR MEMORIAL PHOTO BY REBECCA BOLTON STATE HERITAGE PLACE – No. 14535 This war memorial is significant as a unique tribute to those who served in the First World War. The First World War was a watershed in Australia's history.