Completa Com Letra Ampliada E Sangria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela: Nicolas Maduro’S Cabinet Chair: Peter Derrah

Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela: Nicolas Maduro’s Cabinet Chair: Peter Derrah 1 Table of Contents 3. Letter from Chair 4. Members of Committee 5. Committee Background A.Solving the Economic Crisis B.Solving the Presidential Crisis 2 Dear LYMUN delegates, Hi, my name is Peter Derrah and I am a senior at Lyons Township High School. I have done MUN for all my four years of high school, and I was a vice chair at the previous LYMUN conference. LYMUN is a well run conference and I hope that you all will have a good experience here. In this committee you all will be representing high level political figures in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, as you deal with an incomprehensible level of inflation and general economic collapse, as well as internal political disputes with opposition candidates, the National Assembly, and massive protests and general civil unrest. This should be a very interesting committee, as these ongoing issues are very serious, urgent, and have shaped geopolitics recently. I know a lot of these issues are extremely complex and so I suggest that you do enough research to have at least a basic understanding of them and solutions which could solve them. For this reason I highly suggest you read the background. It is important to remember the individual background for your figure (though this may be difficult for lower level politicians) as well as the political ideology of the ruling coalition and the power dynamics of Venezuela’s current government. I hope that you all will put in good effort into preparation, write position papers, actively speak and participate in moderated and unmoderated caucus, and come up with creative and informed solutions to these pressing issues. -

The Venezuelan Crisis, Regional Dynamics and the Colombian Peace Process by David Smilde and Dimitris Pantoulas Executive Summary

Report August 2016 The Venezuelan crisis, regional dynamics and the Colombian peace process By David Smilde and Dimitris Pantoulas Executive summary Venezuela has entered a crisis of governance that will last for at least another two years. An unsustainable economic model has caused triple-digit inflation, economic contraction, and widespread scarcities of food and medicines. An unpopular government is trying to keep power through increasingly authoritarian measures: restricting the powers of the opposition-controlled National Assembly, avoiding a recall referendum, and restricting civil and political rights. Venezuela’s prestige and influence in the region have clearly suffered. Nevertheless, the general contours of the region’s emphasis on regional autonomy and state sovereignty are intact and suggestions that Venezuela is isolated are premature. Venezuela’s participation in the Colombian peace process since 2012 has allowed it to project an image of a responsible member of the international community and thereby counteract perceptions of it as a “rogue state”. Its growing democratic deficits make this projected image all the more valuable and Venezuela will likely continue with a constructive role both in consolidating peace with the FARC-EP and facilitating negotiations between the Colombian government and the ELN. However, a political breakdown or humanitarian crisis could alter relations with Colombia and change Venezuela’s role in a number of ways. Introduction aimed to maximise profits from the country’s oil production. During his 14 years in office Venezuelan president Hugo Together with Iran and Russia, the Venezuelan government Chávez Frias sought to turn his country into a leading has sought to accomplish this through restricting produc- promotor of the integration of Latin American states and tion and thus maintaining prices. -

The Effect of External Actors on the Courses of Asymmetric Conflicts: Pkk, Ltte, and Farc

KADİR HAS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAM OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS THE EFFECT OF EXTERNAL ACTORS ON THE COURSES OF ASYMMETRIC CONFLICTS: PKK, LTTE, AND FARC TUĞBA SEZGİN MASTER’S THESIS ISTANBUL, MAY, 2019 THE EFFECT OF EXTERNAL ACTORS ON THE COURSES OF ASYMMETRIC CONFLICTS: PKK, LTTE, AND FARC TUĞBA SEZGİN MASTER’S THESIS Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Kadir Has University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s in the Program of International Relations ISTANBUL, MAY, 2019 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………...……………………………………………....vi ÖZET………………………………………………………………………………......vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………….viii DEDICATION ................................................................................................................ ix LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................... x LIST OF FIGURES…………………………………………………………………....xi ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………..…..………………...xii 1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………...……1 1.1 The Origin and Development of the Concept of Asymmetric Conflict……………...1 1.2 Empirical Puzzle and Theoretical Overview of Competing Explanation……………3 1.3 Research Questions………………….…………………………………..…………...5 1.4 Research Design and Methodology………….…………………………...………….6 1.5 The Plan of the Study…………………………………………………..……………8 2. LITERATURE REVIEW .......................................................................................... 9 2.1 The Theories of Asymmetic Conflict…. -

Terrorism, Insurgency, and Drugs Still Threaten America's Southern

No. 2152 June 30, 2008 Terrorism, Insurgency, and Drugs Still Threaten America’s Southern Flank Ray Walser, Ph.D. On March 1, 2008, the Colombian military sanctions against individuals who are illegally sup- attacked a jungle encampment of the Revolution- porting the FARC. ary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), located less In addition, Chávez’s growing ties with Iran than two miles inside Ecuadorian territory. It was appear to open a door for Islamist terrorism and an important operating hub for the FARC, which raise the question of whether the U.S. has done the United States has designated as a foreign terror- enough since 9/11 to protect against backdoor terror- ist organization. Luis Edgar Devia (aka Raul Reyes), ist threats originating in the Western Hemisphere. the FARC’s second in command and top interna- The U.S. needs to explore ways to strengthen vigi- tional strategist, was killed in the raid along with 24 lance and to prevent Iran from exploiting this other guerrillas and supporters. Perhaps more potential conduit to the homeland. important, the Colombian military captured three laptop computers and additional memory devices FARC and drug-related terrorism still threatens belonging to Reyes. progress made in Colombia, the essential U.S. part- ner in the Andes. The U.S. should work to bolster The files on these computers and devices chron- Colombia’s capacity and will to defeat FARC terror- icle the thoughts and actions of the FARC and raise ism by continuing to fund Plan Colombia and by serious questions about the effectiveness of U.S. -

Venezuela: Overview of U.S. Sanctions

Updated April 24, 2019 Venezuela: Overview of U.S. Sanctions For more than a decade, the United States has employed Silva (former defense minister and governor of Trujillo sanctions as a policy tool in response to activities of the State), and Ramón Rodríguez Chacín (former interior Venezuelan government and Venezuelan individuals. These minister and former governor of Guárico); in 2011, Freddy have included sanctions related to terrorism, drug Alirio Bernal Rosales and Amilicar Jesus Figueroa Salazar trafficking, trafficking in persons, antidemocratic actions, (United Socialist Party of Venezuela, or PSUV, politicians), human rights violations, and corruption. Overall, the Major General Cliver Antonio Alcalá Cordones, and Treasury Department has imposed financial sanctions on Ramon Isidro Madriz Moreno (a Venezuelan intelligence 111 individuals, and the State Department has revoked the officer); in 2017, then-Vice President Tareck el Aissami; visas of hundreds of individuals. On January 28, 2019, the and in May 2018, Pedro Luis Martin (a former senior Trump Administration announced sanctions on Venezuela’s intelligence official) and two of his associates. Others state-oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A., or designated include drug trafficker Walid Makled, three dual PdVSA. Several days before the imposition of the PdVSA Lebanese-Venezuelan citizens allegedly involved in a drug sanctions, the United States recognized Juan Guaidó, the money-laundering network, and several Colombian drug head of Venezuela’s National Assembly, as the country’s traffickers with activity in Venezuela. interim president and ceased to recognize Nicolás Maduro as the president of Venezuela. Targeted Sanctions Related to Antidemocratic Actions, Human Rights Violations, and Corruption Terrorism-Related Sanctions In response to increasing repression in Venezuela, Congress Since 2006, U.S. -

The Honorable Connie Mack IV

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 10/23/2020 02:22:05 PM The Honorable Connie Mack IV October 22, 2020 Senador Ivan Cepeda Castro Edificio Nuevo del Congreso Cra. 7 #8-62 Oficina 636B Bogota, Colombia Dear Senator Cepeda: On April 10, 2018, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York announced that a federal grand jury had reviewed material evidence and returned a criminal indictment against Seuxis Paucis Hernandez-Solarte, a/k/a and heretofore Jesus Santrich, a senior commander of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The FARC was designated as a terrorist organization by the U.S. Department of State in 1997 and remains so today. In the indictment, Santrich was charged with conspiracy to produce and export thousands of tons of cocaine to the United States from at least June 2017 until the date of the indictment. The unsealed documents indicated that Santrich was intercepted discussing his intention to traffic cocaine to the United States, and discussed access to laboratories to supply large quantities of the drug and a U.S.- registered aircraft to transport it through and from Colombia. I need not remind you that such activities are in flagrant violation of U.S. and Colombian laws and are core contributing factors to the misery, criminality and death suffered by millions of citizens of both countries to this day. Among all your peers in Colombian politics, you have stood out as the principal political ally of the FARC. Since Santrich was first indicted in 2018, you have publicly expressed your solidarity with him on numerous occasions. -

1 Statement of Celina B. Realuyo* Professor of Practice William J

Statement of Celina B. Realuyo* Professor of Practice William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies at National Defense University on “U.S. Efforts to Counter the Convergence of Terrorism and Crime with the Financial Instrument of National Power” at a Hearing Entitled “Exploring the Financial Nexus of Terrorism, Drug Trafficking and Organized Crime ” Before the Subcommittee on Terrorism and Illicit Finance, Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives March 20, 2018 * The views expressed in this testimony are my own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies, National Defense University, or the Department of Defense. 1 Thank you Chairman Pearce, Vice Chairman Pittenger, Ranking Member Perlmutter, and members of the Subcommittee on Terrorism and Illicit Finance for the opportunity to appear before this committee today to testify on U.S. efforts to counter the convergence of terrorism and crime with the financial instrument of national power. We face a myriad of security threats from revisionist states, aspiring nuclear powers, global terrorism, transnational organized crime, and cyber attacks that have made national security more daunting than ever before. The complexity of these security threats, especially from illicit networks, such as terrorists, criminals, and WMD proliferators, requires nimble, multi-disciplinary, and multilateral approaches to counter these threats effectively. Over the past year, the Trump Administration has issued strategies and policies to address the threats from terrorism and transnational organized crime to U.S. interests at home and abroad, including a new U.S. National Security Strategy. These new strategies recognize financing as one of the most critical of enablers for terrorism, crime, and corruption and include financial and economic measures that seek to better detect, dismantle, and deter these illicit threat networks. -

Routes of Entry for Artists and Entertainers Routes of Entry for Artists and Entertainers

Routes of entry for artists and entertainers Routes of entry for artists and entertainers This leaflet sets out the main immigration routes for artists and entertainers coming to the UK for visits or work. It explains whether you need a visa before you enter the UK and gives an overview of the routes and the process for applying. It is essential that anyone who is considering making an application, or sponsoring an applicant if they intend to work in the UK, consults the detailed guidance that is available on the Home Office website at www.ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk. General visa information You may be required to obtain ‘entry clearance’ (a visa) before travelling to the UK, depending on your nationality and your reason for wanting to travel to the UK. More information on entry clearance and visas can be found on the ‘general visa information’ page on the UK Border Agency’s website. • If you are a visa national you will need to obtain a visa before you come to the UK. • If you are a non-visa national, you may need to obtain a visa if you want to come to the UK for up to 6 months. You will definitely need a visa if you want to come here for more than 6 months. More information is available on the Non-visa nationals page. How and where to apply You must be outside the UK, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man when you apply for entry clearance. You can apply for a visit visa at our visa application centres in any country; you do not have to apply within your country of residence. -

A Bridge to Firmer Ground: Learning from International Experiences to Support Pathways to Solutions in the Syrian Refugee Context

A BRIDGE TO FIRMER GROUND: LEARNING FROM INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCES TO SUPPORT PATHWAYS TO SOLUTIONS IN THE SYRIAN REFUGEE CONTEXT FULL RESEARCH REPORT MARCH 2021 The Durable Solutions Platform (DSP) aims to generate knowledge that informs and inspires forwardthinking policy and practice on the long-term future of displaced Syrians. Since its establishment in 2016, the DSP has developed research projects and supported advocacy efforts on key questions regarding durable solutions for Syrians. In addition, DSP has strengthened the capacity of civil society organizations on solutions to displacement. For more, visit https://www.dsp-syria.org/ The nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute seeks to improve immigration and integration policies through authoritative research and analysis, opportunities for learning and dialogue, and the development of new ideas to address complex policy questions. The Institute is guided by the belief that countries need to have sensible, well thought- out immigration and integration policies in order to ensure the best outcomes for both immigrants and receiving communities. For more, visit https://www.migrationpolicy.org/ This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Regional Development and Protection Programme (RDPP II) for Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq, which is supported by the Czech Republic, Denmark, the European Union, Ireland and Switzerland. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Durable Solutions Platform and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the RDPP or its donors. A BRIDGE TO FIRMER GROUND Acknowledgements This report was authored by Camille Le Coz, Samuel Davidoff-Gore, Timo Schmidt, Susan Fratzke, Andrea Tanco, Belen Zanzuchi, and Jessica Bolter. -

The Middle Eastern-Latin American Terrorist Connection

Foreign Policy Research Institute E-Notes A Catalyst for Ideas Distributed via Email and Posted at www.fpri.org May 2011 THE MIDDLE EASTERN-LATIN AMERICAN TERRORIST CONNECTION By Vanessa Neumann Vanessa Neumann is an Associate of the University Seminar on Latin America at the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) at Columbia University. A native Venezuelan, Dr. Neumann has worked as a journalist in Caracas, London and the United States. She is Editor-at-Large of Diplomat, a London-based magazine to the diplomatic community and a regular contributor to The Weekly Standard on Latin American politics. In a global triangulation that would excite any conspiracy buff, the globalization of terrorism now links Colombian FARC with Hezbollah, Iran with Russia, elected governments with violent insurgencies, uranium with AK-103s, and cocaine with oil. At the center of it all, is Latin America—especially the countries under the influence of Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez. The most publicized (and publicly contested) connection between Hugo Chávez and the Colombian narcoterrorist organization Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) was revealed after the March 2008 Colombian raid on the FARC camp in Devía, inside Ecuador, where a laptop was discovered that apparently belonged to Luis Edgar Devía Silva (aka, “Raúl Reyes”), head of FARC’s International Committee (COMINTER). The Colombian government under then- President Álvaro Uribe announced that Interpol had certified the authenticity of the contents of the computer disks, whose files traced over US$ 200 million funneled to the FARC through the Venezuelan state-owned, and completely Chávez- dominated, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). -

Curbing the Threat to Venezuela from Violent Groups

A Glut of Arms: Curbing the Threat to Venezuela from Violent Groups Latin America Report N°78 | 20 February 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Armed Groups, Crime and the State ................................................................................ 4 A. Guerrillas ................................................................................................................... 4 B. Colectivos ................................................................................................................... 7 C. Paramilitaries ............................................................................................................. 11 D. Criminal Groups ........................................................................................................ 12 III. Armed Groups in a Political Agreement .......................................................................... 16 IV. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 18 APPENDICES A. Map of Venezuela ............................................................................................................ -

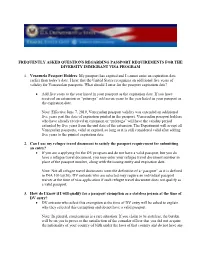

Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Passport Requirements for the Diversity Immigrant Visa Program

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS REGARDING PASSPORT REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DIVERSITY IMMIGRANT VISA PROGRAM 1. Venezuela Passport Holders: My passport has expired and I cannot enter an expiration date earlier than today’s date. I hear that the United States recognizes an additional five years of validity for Venezuelan passports. What should I enter for the passport expiration date? Add five years to the year listed in your passport as the expiration date. If you have received an extension or “prórroga” add seven years to the year listed in your passport as the expiration date. Note: Effective June 7, 2019, Venezuelan passport validity was extended an additional five years past the date of expiration printed in the passport. Venezuelan passport holders who have already received an extension or “prórroga” will have the validity period extended by five years from the end date of the extension. The Department will accept all Venezuelan passports, valid or expired, so long as it is still considered valid after adding five years to the printed expiration date. 2. Can I use my refugee travel document to satisfy the passport requirement for submitting an entry? If you are a applying for the DV program and do not have a valid passport, but you do have a refugee travel document, you may enter your refugee travel document number in place of the passport number, along with the issuing entity and expiration date. Note: Not all refugee travel documents meet the definition of a “passport” as it is defined in INA 101(a)(30). DV entrants who are selected may require an individual passport waiver at the time of visa application if such refugee travel document does not qualify as a valid passport.