Retailing and Hawaii's Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Friday, March 17, 2017 Media Contacts: Maggie Jarrett, CommPac (808) 543-3560 Gene Davis, RMHC-HI (808) 973-5683, Ext. 223 RONALD McDONALD HOUSE HAWAII CELEBRATES THIRTY YEARS OF KEEPING FAMILIES CLOSE Over 11,500 Families provided with “home-away-from-home” since 1987 HONOLULU – Ronald McDonald House Charities® of Hawaii (RMHC-Hawaii) is marking three decades of assisting families with seriously ill children from the neighbor islands and throughout the Pacific Rim who must travel to Oahu for treatments. A year’s worth of festivities, events and outreach efforts are scheduled to create awareness of the services available and to give thanks to all who have supported the charity since its inception. RMHC-Hawaii opened its first house on Judd Hillside Road in Manoa Valley on March 27, 1987 and added a second Ronald McDonald House on Oahu Avenue in 2006. The two Houses operate 24 hours a day, 365 days a year and together have provided a “home-away-from-home” for more than 11,500 families. The Ronald McDonald House Family Room at Kapiolani Medical Center for Women & Children opened in 2003 and provides respite and assistance for more than 9,000 people annually. “Over the years, there have been countless moments that have touched us deeply, reminding us of the important work we do,” said Jerri Chong, Ronald McDonald House Charities of Hawaii president. “The Ronald McDonald House provides a supportive environment for families caring for children who are undergoing treatments for illnesses. We are so appreciative of our donors, volunteers and staff that make it possible to care for these families. -

Night Drop Savings Bank

Night Drop Savings Bank Oahu Ala Moana Center Branch Kaneohe Branch Town Center of Mililani Branch UH Campus Branch 1450 Ala Moana Boulevard 45-1144 Kamehameha Highway 95-1249 Meheula Parkway Hemenway Hall Suite 1255 Suite 100 Suite 126 2445 Campus Road Honolulu, HI 96814-4613 Kaneohe, HI 96744-3272 Mililani, HI 96789-1787 Honolulu, HI 96822-2216 (808) 973-4864 (808) 233-4570 (808) 623-2878 (808) 973-6211 Ewa Branch Kapiolani Branch Nanakuli Wahiawa Branch Laulani Village Shopping Center 1600 Kapiolani Boulevard Sack N Save Branch 649 California Avenue 91-1101 Keaunui Drive Suite 205 87-2070 Farrington Highway Wahiawa, HI 96786-1941 Ewa Beach, HI 96706-6340 Honolulu, HI 96814-3897 Suite G (808) 622-4179 (808) 685-4618 (808) 946-2802 Waianae, HI 96792-3733 (808) 673-6600 Waianae Branch Haleiwa Branch Kapolei Branch Waianae Mall Haleiwa Shopping Plaza 888 Wakea Street Pearl City Branch 86-120 Farrington Highway 66-197 Kamehameha Highway Kapolei, HI 96707 Pearl City Shopping Center Building 1 Suite A (808) 674-2288 850 Kamehameha Highway Waianae, HI 96792-3065 Haleiwa, HI 96712-1400 Suite 164 (808) 673-2606 (808) 637-5042 Main Branch Pearl City, HI 96782-2657 1001 Bishop Street (808) 455-4138 Waikiki Branch Hawaii Kai Branch Honolulu, HI 96813-3400 Waikiki Trade Center Hawaii Kai Towne Center (808) 523-6844 Pearlridge Branch 2255 Kuhio Avenue 333 Keahole Street 98-200 Kamehameha Highway Suite 105 Honolulu, HI 96825-3406 Makiki Branch 1st Floor Honolulu, HI 96815-2681 (808) 395-2308 1209 Piikoi Street Aiea, HI 96701-4395 (808) 923-1102 Honolulu, -

The Power of Giving

THE POWER OF GIVING 2010 Annual Report HARNESSING HEMOGLOBIN CHRISTOPHER CHUN HEMOGLOBIN HERO Blood. It doesnʼt just help us to live our lives, but helps to give life to others. When itʼs needed, Hemoglobin Hero and donors like Christopher Chun come to the rescue! Hemoglobin Heroʼs iron-rich, oxygen-carrying protein is present in the red blood cells of donors like Christopher, who started giving blood in 1980 at his company drive. It wasnʼt until his mother became ill in 1990 that he made blood donation a lifesaving habit. “I saw blood in real terms, and I was inspired to give more often,” says the century donor with characteristic enthusiasm . “Now, giving blood is part of my routine. You donʼt have to be Superman to save a life!” PRESIDENT & CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE At Blood Bank of Hawaii, we need not look far to find heroes. We see them every day during a visit to our donor room, or to a Lifesaver Club, school or community drive. They represent all ages, ethnicities and walks of life. They roll up their sleeves and quietly engage in one of life’s most altruistic services – giving the gift of life. We are proud to know these extraordinary heroes, and to serve as the critical link between the donors and Hawaii’s hospitals. As new treatments and procedures help save more patients and improve the quality of their lives, the need for blood is more vital than ever. Hawaii’s volunteer blood donors enable the use of new therapies and technologies, and make recovery a reality for countless people. -

Michael Kors® Make Your Move at Sunglass Hut®

Michael Kors® Make Your Move at Sunglass Hut® Official Rules NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE OR PAYMENT WILL NOT INCREASE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED BY LAW OR REGULATION and outside the fifty United States (and the District of ColuMbia). Subject to all federal, state, and local laws, regulations, and ordinances. This Gift ProMotion (“Gift Promotion”) is open only to residents of the fifty (50) United States and the District of ColuMbia ("U.S.") who are at least eighteen (18) years old at the tiMe of entry (each who enters, an “Entrant”). 1. GIFT PROMOTION TIMING: Michael Kors® Make Your Move at Sunglass Hut® Gift Promotion (the “Gift ProMotion”) begins on Friday, March 22, 2019 at 12:01 a.m. Eastern Time (“ET”) and ends at 11:59:59 p.m. ET on Wednesday, April 3, 2019 (the “Gift Period”). Participation in the Gift Promotion does not constitute entry into any other promotion, contest or game. By participating in the Gift Promotion, each Entrant unconditionally accepts and agrees to comply with and abide by these Official Rules and the decisions of Luxottica of America Inc., 4000 Luxottica Place, Mason, OH 45040 d/b/a Sunglass Hut (the “Sponsor”) and WYNG, 360 Park Avenue S., 20th Floor, NY, NY 10010 (the “AdMinistrator”), whose decisions shall be final and legally binding in all respects. 2. ELIGIBILITY: Employees, officers, and directors of Sponsor, Administrator, and each of their respective directors, officers, shareholders, and employees, affiliates, subsidiaries, distributors, -

From Our House to Yours Aloha Newsletter of Ronald Mcdonald House Charities® of Hawaii Vol

From Our House to Yours Aloha www.RonaldHouseHawaii.org Newsletter of Ronald McDonald House Charities® of Hawaii Vol. XVII, Issue 1, March 2017 Message from our President Aloha! the RMH-Family Room to 2017 marks assist 30 years of having families Ronald McDonald spending House in Hawaii. all of their So much has 1me at happened over their the past three child’s The Judd Hillside Ronald McDonald House, circa Jerri Chong decades. We’ve bedside. 1987, preparing for families. grown; we’ve This li2le slice of the expanded our reach; we added Ronald McDonald House receives more programs and opened a second house; than 9,000 visitors each year and has we’ve doubled the number of families welcomed and provided a place of we’re able to serve. Some1me this comfort and support to more than year, we will surpass 27,000 people 120,000 people – families of served since opening, and reach hospitalized children – since opening 125,000 room nights provided for in 2003. families at the Ronald McDonald Each of these families has a unique House. story and has traveled their own dis1nc1ve path. Most will be changed The Judd Hillside House, as it looks today, a home- When the need grew for a respite away-from-home. center at Kapiolani Medical Center, we forever because of their experience of partnered with the hospital to create having a seriously ill child. We are just Another great chance for you to glad that in some way, we may have reconnect with Ronald McDonald helped make their journey less House is by joining us at out 30th 2017 RMHC-HI burdensome and provided emo1onal Anniversary Mahalo events on all the and prac1cal support when they Board of Directors islands. -

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 Gamestop Dimond Center 80

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 GameStop Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard #3-118 Anchorage AK 99515 665 1703 (907) 272-7341 GameStop Anchorage 5th Ave. Mall 320 W. 5th Ave, Suite 172 Anchorage AK 99501 665 6139 (907) 332-0000 GameStop Tikahtnu Commons 11118 N. Muldoon Rd. ste. 165 Anchorage AK 99504 665 6803 (907) 868-1688 GameStop Elmendorf AFB 5800 Westover Dr. Elmendorf AK 99506 75 1833 (907) 474-4550 GameStop Bentley Mall 32 College Rd. Fairbanks AK 99701 665 3219 (907) 456-5700 GameStop & Movies, Too Fairbanks Center 419 Merhar Avenue Suite A Fairbanks AK 99701 665 6140 (907) 357-5775 GameStop Cottonwood Creek Place 1867 E. George Parks Hwy Wasilla AK 99654 665 5601 (205) 621-3131 GameStop Colonial Promenade Alabaster 300 Colonial Prom Pkwy, #3100 Alabaster AL 35007 701 3915 (256) 233-3167 GameStop French Farm Pavillions 229 French Farm Blvd. Unit M Athens AL 35611 705 2989 (256) 538-2397 GameStop Attalia Plaza 977 Gilbert Ferry Rd. SE Attalla AL 35954 705 4115 (334) 887-0333 GameStop Colonial University Village 1627-28a Opelika Rd Auburn AL 36830 707 3917 (205) 425-4985 GameStop Colonial Promenade Tannehill 4933 Promenade Parkway, Suite 147 Bessemer AL 35022 701 1595 (205) 661-6010 GameStop Trussville S/C 5964 Chalkville Mountain Rd Birmingham AL 35235 700 3431 (205) 836-4717 GameStop Roebuck Center 9256 Parkway East, Suite C Birmingham AL 35206 700 3534 (205) 788-4035 GameStop & Movies, Too Five Pointes West S/C 2239 Bessemer Rd., Suite 14 Birmingham AL 35208 700 3693 (205) 957-2600 GameStop The Shops at Eastwood 1632 Montclair Blvd. -

Land Cleared at Bellows Using Bulldozers, Road Graders, Finally Get a Chance to Get out and by Sgt Inez J

Selective Reenlistment Program Rent Plus System Cowboy No more bonus money after Maximum rental allowance increase Refueler driver lives March 30 should reflect in Feb. 28 paycheck for a rodeo See Page A-2 See Page A-6 See Page B-1 HAWAII MARINE Voluntary payment for delivery to MCAS housing/$1 per four week period. VOL. 12 NO. 6 KANEOHE BAY, HAWAII. FEB. 9, 1983 TWENTY PAGES Hands-on-training Land cleared at Bellows Using bulldozers, road graders, finally get a chance to get out and by Sgt Inez J. Stoner dump trucks and a crane, 10-man use the equipment,7 said Corporal crews are clearing about 20 acres Mike Reynolds, a 21-year-old Marines from the Heavy of land each day. The brush Equipment Platoon Engineer mechanic from Decatur, Ill. Company, Brigade ranges in height from four to 18 "It's nice when you're actually Service feet with some trees as tall as 50 Support Group are clearing 122.6 doing the job you were trained feet. According to Wood, the crews for," said Private First Class Cliff acres of land at Bellows Air Force are rotated Station. every two weeks to Enright, III, a heavy equipment The clearing job is not allow all of the Marines in the only providing the Marines with operator from Albany, N.Y. "It platoon to train with the gives you more confidence with invaluable training, but is also equipment. saving the government more than your skills as an operator." $200,000. The hands-on training was also "We should do a lot more of experience for Corporal David According to Chief Warrant this," said Sergeant Kenneth Officer-3 David Wood, platoon Laumeyer, a combat engineer Holland, heavy equipment from Peru, Ind. -

Waipahu, Hawaii

WAIPAHU, HAWAII PROPERTY OVERVIEW WAIKELE PREMIUM OUTLETS® WAIPAHU, HI WAIKELE PREMIUM OUTLETS WAIPAHU, HI MAJOR METROPOLITAN AREAS SELECT TENANTS Honolulu: 15 miles adidas, AllSaints, Armani Outlet, Banana Republic Factory Store, Calvin Klein, Coach, Cole Haan, Converse, The Cosmetics Company Store, FURLA, GUESS Factory Store, kate spade new york, LACOSTE, Levi’s RETAIL Outlet Store, Michael Kors, OshKosh B’gosh, Polo Ralph Lauren Factory Store, Saks Fifth Avenue OFF 5TH, Skechers, Swarovski, Tommy GLA (sq. ft.) 219,000; 57 stores Bahama, Tommy Hilfiger, Tory Burch, True Religion, Tumi, UGG®, Vera Bradley, Watch Station International OPENING DATES Opened 1994 Renovated 2015 TOURISM / TRAFFIC According to the HawaiiTourismAuthority.org, over 9.9 million visitors traveled to Hawaii in 2018. Oahu leads all other islands in attracting the PARKING RATIO most arrivals (5.9 million). Visitors stayed an average of 6.87 days on Oahu with shopping expenditures in Hawaii topping $17.82 billion in 3.6:1 2018. Waikele Premium Outlets is the only outlet center on the island of Oahu and is a popular prepackaged shopping tour stop for Japanese, Chinese, South Korean, and Australian visitors. RADIUS POPULATION 15 miles: 815,493 30 miles: 998,555 LOCATION / DIRECTIONS AVERAGE HH INCOME Waikele Premium Outlets is located in “Central Oahu,” Waipahu, Hawaii at 94-790 Lumiaina Street, 15 miles northwest of Honolulu directly off 30 miles: $99,136 I-H-1, Exit 7. Information as of 5/1/19. Source: SPG Research; trade area demographic information per STI: PopStats (2018). OTHER RETAIL SHOPPING CENTERS GROSS LEASABLE AREA ANCHORS DISTANCE / DRIVE-TIME Pearlridge Center Aiea, HI 1,290,000 sf Macy's, Sears 7 miles / 15 minutes Ka Makana Ali'i 860,000 sf Macy’s, Consolidated Theatres, 7 miles / 15 minutes Kapolei, HI Hampton Inn & Suites by Hilton Ala Moana Center 2,300,000 sf Bloomingdale's, Macy's, Neiman Marcus, 15 miles / 30 minutes Honolulu, HI Nordstrom, Shirokiya Ward Village Shops 1,000,000 sf Nordstrom Rack, T.J. -

Pearlridge Center Hawaii

PEARLRIDGE CENTER HAWAII 98-1005 Moanalua Rd., Aiea, HI 96701 TABLE OF CONTENTS Market Snapshot Location By the Numbers Local Landscape Property Highlights Portfolio Events and Activations MARKET SNAPSHOT In early 2019, Located in Aiea, a census-designated place in the city and county of Honolulu, Hawaii, Pearlridge the $30 million Center draws residents from central and west Oahu and is not dependent on the fluctuating travel industry. The property’s location provides proximity renovation of to employment centers as well as a strong residential base. West Oahu is one of the fastest-growing regions in the state and has become one of the most sought- Pearlridge Makai after places in which to live and work. Honolulu is the capital, largest city, and main airport and seaport of the Hawaiian Islands. was completed. Honolulu and the surrounding area’s steady population and job growth is driven primarily by The renovation tourism and government (military) sectors. The region is also working to attract more high technology companies, providing a truly diverse employment enhanced foundation. Nearby is Joint Base Pearl Harbor / Hickam, which has 12,597 civilians employed on base and which contributes significantly to the mall’s Pearlridge Center customer base. Pali Momi Medical Center is a major employer located right outside the shopping center, bringing additional customers into the mall. customers’ The University of Hawaii - West Oahu, with enrollment of 3,400 students (and anticipating 20,000 students shopping and by 2020), is located 10 miles west of the property. Waikiki Beach is a major tourist destination on the island, as is the Pearl Harbor Visitors Center, dining experience. -

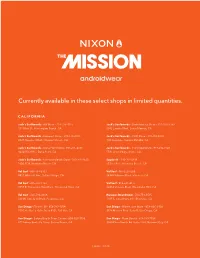

Currently Available in These Select Shops in Limited Quantities

Currently available in these select shops in limited quantities. CALIFORNIA Jack’s Surfboards - HB Store - 714-536-4516 Jack’s Surfboards - Santa Monica Store - 310-450-6569 101 Main St., Huntington Beach, CA 2012 Lincoln Blvd., Santa Monica, CA Jack’s Surfboards - Newport Store - 949-673-2300 Jack’s Surfboards - CDM Store - 949-718-0001 2727 Newport Blvd., Newport Beach, CA 900 Avocado, Corona Del Mar, CA Jack’s Surfboards - Dana Point Store - 949-276-8080 Jack’s Surfboards - Irvine Spectrum - 949-242-7020 34320 PCH # C, Dana Point, CA 5581 Alton Pkwy., Irvine, CA Jack’s Surfboards - Hermosa Beach Store - 310-374-7873 Spyder II - 310-374-2494 1630 PCH, Hermosa Beach, CA 65 Pier Ave., Hermosa Beach, CA Val Surf - 818-769-3337 Val Surf - 661-222-7288 4810 Whitsett Ave., Valley Village, CA 24140 Valencia Blvd., Valencia, CA Val Surf - 805- 497-1166 Val Surf - 818-225-8177 3055 E. Thousand Oaks Blvd., Thousand Oaks, CA 22864 Ventura Blvd., Woodland Hills, CA Val Surf - 626-796-0668 Hansens Boardroom - 760-753-6595 169 W. Colorado Blvd., Pasadena, CA 1105 S. Coast Hwy. 101, Encinitas, CA Sun Diego - Flower Hill - 858-793-1054 Sun Diego - Wavehouse Store - 858-866-0108 2720 Via De La Valle, Suite #101, Del Mar, CA 3126 Mission Blvd. Suite B, San Diego, CA Sun Diego - Solana Beach Town Center - 858-523-1733 Sun Diego - Plaza Bonita - 619-399-7959 677 Lomas Santa Fe Drive, Solana Beach, CA 3030 Plaza Bonita Rd. Suite 1160, National City, CA nixon.com CALIFORNIA Sun Diego - Fashion Valley Mall - 619-268-2295 Sun Diego - University Town Center - 858-646-0632 7007 Friars Rd. -

NEOSTAR RETAIL GROUP INC Mailing Address Business Address 2250 WILLIAM D

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 8-K Current report filing Filing Date: 1996-11-29 | Period of Report: 1996-11-27 SEC Accession No. 0000950134-96-006622 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER NEOSTAR RETAIL GROUP INC Mailing Address Business Address 2250 WILLIAM D. TATE 2250 WILLIAM D. TATE CIK:932790| IRS No.: 752559376 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 0129 AVENUE AVENUE Type: 8-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 000-25272 | Film No.: 96674327 GRAPEVINE TX 76051 GRAPEVINE TX 76051 SIC: 5734 Computer & computer software stores (817) 424-2000 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document 1 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 ----------------------------------- Date of Report November 27, 1996 NeoStar Retail Group, Inc. ------------------------------------------------------ (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) Delaware 0-25272 75-2559376 ---------------------------- ------------- ------------------- (State or other jurisdiction (Commission (IRS Employer of incorporation) File Number) Identification No.) 2250 William D. Tate Avenue, Grapevine, Texas 76051 ---------------------------------------------- ---------- (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: (817) 424-2000 ---------------- 2 Item 5. Other Events On September 16, 1996, NeoStar Retail Group, Inc., a Delaware corporation (the "Company'), and its direct and indirect subsidiaries, Babbage's, Inc., a Texas corporation ("Babbage's"), Software Etc. Stores, Inc., a Delaware corporation ("Software"), Augusta Enterprises, Inc., a Delaware corporation, and Chasada, a Pennsylvania business trust, filed voluntary petitions under Chapter 11 of the United States Bankruptcy Code, Case No. -

4Q2016 Retail Market Report.Indd

Oahu | Hawaii Research & Forecast Report RETAIL MARKET Year-End 2016 Delivery of Ka Makana Alii Regional Mall Contributes to Market Growth Mike Hamasu Director of Research | Hawaii Oahu’s retail marketplace received a 502,178 square foot boost “We anticipate Oahu’s retail in net absorption in 2016 as Ala Moana Center, International market to continue to strengthen Market Place and Ka Makana Alii developments added nearly 1.4 million square feet of additional inventory. However, more than as the introduction of new 600,000 square feet of this new space is either vacant or under retailers add to the vibrancy of construction, resulting in a vacancy rate spike. our market.” Over the past two years, the island-wide vacancy rate doubled Nathan A. Fong (B), Senior Vice President from 4.09% at year-end 2014 to 8.44% currently. The last time vacancy rates exceeded 8% was in 2003 when JCPenney shut Market Indicators Year End down and left signifi cant vacancies at Ala Moana Center and Relative to prior quarter 2016 Pearlridge Center. VACANCY Colliers anticipates that vacancy rates will steadily decline NET ABSORPTION in 2017 when a projected 400,000 square feet of the new CONSTRUCTION inventory becomes occupied. RENTAL RATE Oahu Retail Net Absorption vs. Vacancy Rate Summary Statistics Year End 2016 Retail Market 8.44% 600,000 9.00% YTD Net Absorption 502,178 SF 502,178 8.00% Vacancy Rate 8.44% 500,000 7.00% Average Asking Rent Range $3.52 to $4.33 psf/mo 400,000 6.00% Average Asking Rent NNN $3.92 psf/mo 5.00% Average Operating Exp.