SAM” EVANS 1 B-24 LIBERATOR COMBAT PILOT, 1943-1945, Serial No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Happy Bottom Eighth in the East

Ridgewell Airfield Commemorative Association Happy Bottom 70 years ago this month a famous American actor came to Ridgewell. Fresh from filming ‘Mr. Winkle Goes to War’, Hollywood star, Edward G. Robinson, arrived to christen a new B-17 in honour of his wife. On 5 July 1944, Ridgewell came to a standstill. Not just for the war, but for movie actor Edward G. Robinson (alias "Rico" Bandello, a small-time crook from the movie, Little Caesar) who’d arrived to christen a new B- 17G which had recently been assigned to the 532nd Bomb Squadron. Base Chaplain James Good Brown was one of the first to greet him. He was left suitably impressed. “What a man!” Brown later wrote. “Of all the actors who came to the base, he showed the most human interest. He was never acting. He just wanted to walk around the base talking to the President—Dave Osborne men, and the men wanted to talk to him.” Chairman—Jim Tennet Robinson broke his gangster persona making the watching Treasurer—Jenny Tennet Secretary—Mike Land men howl with laughter when he announced that he was Membership Secretary—Alan Steel naming the new aircraft ‘Happy Bottom’ after his wife, Historian—Chris Tennet Gladys, which he cleverly mispronounced, ‘Glad Ass’. Volunteer—Monica Steel The actor was a big hit. “When he left the base, he left with Aki Bingley several thousand men as his friends,” said Chaplain Brown. DEDICATED TO THE MEN OF RAF 90 SQUADRON, 94 AND 95 MAINTENANCE UNITS AND USAAF 381ST BOMB GROUP Newsletter JULY 2014 Sadly, Happy Bottom didn’t fare so well. -

Date Pilot Aircraft Serial No Station Location 6/1/1950 Eggert, Wayne W

DATE PILOT AIRCRAFT SERIAL_NO STATION LOCATION 6/1/1950 EGGERT, WAYNE W. XH-12B 46-216 BELL AIRCRAFT CORP, NY RANSIOMVILLE 3 MI N, NY 6/1/1950 LIEBACH, JOSEPH G. B-29 45-21697 WALKER AFB, NM ROSWELL AAF 14 MI ESE, NM 6/1/1950 LINDENMUTH, LESLIE L F-51D 44-74637 NELLIS AFB, NV NELLIS AFB, NV 6/1/1950 YEADEN, HUBERT N C-46A 41-12381 O'HARE IAP, IL O'HARE IAP 6/1/1950 SNOWDEN, LAIRD A T-7 41-21105 NEW CASTLE, DE ATTERBURY AFB 6/1/1950 BECKLEY, WILLIAM M T-6C 42-43949 RANDOLPH AFB, TX RANDOLPH AFB 6/1/1950 VAN FLEET, RAYMOND A T-6D 42-44454 KEESLER AFB, MS KEESLER AFB 6/2/1950 CRAWFORD, DAVID J. F-51D 44-84960 WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB, OH WEST ALEXANDRIA 5 MI S, OH 6/2/1950 BONEY, LAWRENCE J. F-80C 47-589 ELMENDORF AAF, AK ELMENDORF AAF, AK 6/2/1950 SMITH, ROBERT G F-80B 45-8493 FURSTENFELDBRUCK AB, GER NURNBERG 6/2/1950 BEATY, ALBERT C F-86A 48-245 LANGLEY AFB, VA LANGLEY AFB 6/2/1950 CARTMILL, JOHN B F-86A 48-293 LANGLEY AFB, VA LANGLEY AFB 6/2/1950 HAUPT, FRED J F-86A 49-1026 KIRTLAND AFB, NM KIRTLAND AFB 6/2/1950 BROWN, JACK F F-86A 49-1158 OTIS AFB, MA 8 MI S TAMPA FL 6/3/1950 CAGLE, VICTOR W. C-45F 44-87105 TYNDALL FIELD, FL SHAW AAF, SC 6/3/1950 SCHOENBERGER, JAMES H T-7 43-33489 WOLD CHAMBERLIAN FIELD, MN WOLD CHAMBERLAIN FIELD 6/3/1950 BROOKS, RICHARD O T-6D 44-80945 RANDOLPH AFB, TX SHERMAN AFB 6/3/1950 FRASER, JAMES A B-50D 47-163 BOEING FIELD, SEATTLE WA BOEING FIELD 6/4/1950 SJULSTAD, LLOYD A F-51D 44-74997 HECTOR APT, ND HECTOR APT 6/4/1950 BUECHLER, THEODORE B F-80A 44-85153 NAHA AB, OKI 15 MI NE NAHA AB 6/4/1950 RITCHLEY, ANDREW J F-80A 44-85406 NAHA AB, OKI 15 MI NE NAHA AB 6/4/1950 WACKERMAN, ARNOLD G F-47D 45-49142 NIAGARA FALLS AFB, NY WESTCHESTER CAP 6/5/1950 MCCLURE, GRAVES C JR SNJ USN-27712 NAS ATLANTA, GA MACDILL AFB 6/5/1950 WEATHERMAN, VERNON R C-47A 43-16059 MCCHORD AFB, WA LOWRY AFB 6/5/1950 SOLEM, HERMAN S F-51D 45-11679 HECTOR APT, ND HECTOR APT 6/5/1950 EVEREST, FRANK K YF-93A 48-317 EDWARDS AFB, CA EDWARDS AFB 6/5/1950 RANKIN, WARNER F JR H-13B 48-800 WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB, OH WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB 6/6/1950 BLISS, GERALD B. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

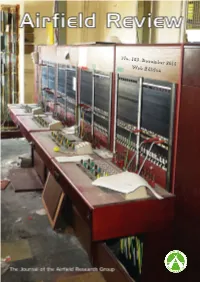

No. 153 December 2016 Web Edition

No. 153 December 2016 Web Edition Airfield Research Group Ltd Registered in England and Wales | Company Registration Number: 08931493 | Registered Charity Number: 1157924 Registered Office: 6 Renhold Road, Wilden, Bedford, MK44 2QA To advance the education of the general public by carrying out research into, and maintaining records of, military and civilian airfields and related infrastructure, both current and historic, anywhere in the world All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the author and copyright holder. Any information subsequently used must credit both the author and Airfield Review / ARG Ltd. T HE ARG MA N ag E M EN T TE am Directors Chairman Paul Francis [email protected] 07972 474368 Finance Director Norman Brice [email protected] Director Peter Howarth [email protected] 01234 771452 Director Noel Ryan [email protected] Company Secretary Peter Howarth [email protected] 01234 771452 Officers Membership Secretary & Roadshow Coordinator Jayne Wright [email protected] 0114 283 8049 Archive & Collections Manager Paul Bellamy [email protected] Visits Manager Laurie Kennard [email protected] 07970 160946 Health & Safety Officer Jeff Hawley [email protected] Media and PR Jeff Hawley [email protected] Airfield Review Editor Graham Crisp [email protected] 07970 745571 Roundup & Memorials Coordinator Peter Kirk [email protected] C ON T EN T S I NFO rmati ON A ND RE G UL ar S F E at U R ES Information and Notices .................................................1 AW Hawksley Ltd and the Factory at Brockworth ..... -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

RAF Wymeswold Part 3

Part Three 1956 to 1957 RAF Wymeswold– Postwar Flying 1948 to 1970 (with a Second World War postscript) RichardKnight text © RichardKnight 2019–20 illustrations © as credited 2019–20 The moral rights of the author and illustrators have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the author, except for brief passages quoted in reviews. Published as six downloadablePDFfiles only by the author in conjunction with the WoldsHistorical Organisation 2020. This is the history of an aerodrome, not an official document. It has been drawn from memories and formal records and should give a reliable picture of what took place. Any discrepancies are my responsibility. RichardKnight [email protected]. Abbreviations used for Royal Air Force ranks PltOff Pilot Officer FgOff Flying Officer FltLt Flight Lieutenant SqnLdr Squadron Leader WgCdr Wing Commander GpCapt Group Captain A Cdr Air Commodore Contents This account of RAF Wymeswoldis published as six free-to-downloadPDFs. All the necessary links are at www.hoap/who#raf Part One 1946 to 1954 Farewell Dakotas; 504 Sqn.Spitfires to Meteors Part Two 1954 to 1955 Rolls Roycetest fleet and sonic bangs; 504 Sqn.Meteors; RAFAAir Display; 56 SqnHunters Part Three 1956 to 1957 The WymeswoldWing (504 Sqn& 616 SqnMeteors); The WattishamWing (257 Sqn& 263 SqnHunters); Battle of Britain ‘At Home’ Part Four Memories from members of 504 Sqn On the ground and in the air Part Five 1958 to 1970 Field Aircraft Services: civilian & military aircraft; No. 2 Flying Training School; Provosts & Jet Provosts Part Six 1944 FrederickDixon’simages: of accommodation, Wellingtons, Hampdens, Horsasand C47s Videos There are several videos about RAF Wymeswold, four by RichardKnight:, and one by Cerrighedd: youtu.be/lto9rs86ZkY youtu.be/S6rN9nWrQpI youtu.be/7yj9Qb4Qjgo youtu.be/dkNnEV4QLwc www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTlMQkKvPkI You can try copy-and-pasting these URLsinto your browser. -

Qjlir Fa Fentpalnrf

QJlir f a fentpalnrf Volume 16. Issue ^29. DURHAM, N. H., JUNE 3, 1926. Price, 10 Cents HARRY W. STEERE, JR. BOOK AND SCROLL PRES. HETZEL ON PRESIDENT OF CLASS EARLY TRYOUTS HOST TO VISITORS PLANS FOR ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT The final meeting of the year of Leads Graduates For Next Two Years FOR DEBATERS OF UNIVERSITY STAND COMPLETED TOUR OF EUROPE Book and Scroll was held in the par —Miss Marian Arthur Is Vice- lor of Smith H all last Monday night President— Class Day Speak Tau Kappa Alpha Latest at eight o’clock. Representatives of Group to Hear Lectures ers Chosen Commencement Speech by Dr. William F. Anderson By Well-Known Statesman Honorary Campus Society T h e N e w H a m p s h ir e , T h e Golden Bishop of the Methodist-Episcopal Church, Boston B u ll and Spires were guests of the Harry W. Steere, Jr., Amesbury, organization. WILL LEAVE JUNE 23 N. E. LEAGUE FORMED COMMENCEMENT BALL FRIDAY BEGINS PROGRAM Mass., was elected president of the The meeting was opened with in graduating class of the university at troductory remarks from President Party Will Consist of Educators, Ed Two Subjects for Debates— Probably a meeting of the seniors held in Neville, who stressed the necessity The Rev. Vaughan Dabney, Pastor of Second Church, Dorchester, Mass. to itors, and Other Men of Public Life Men’s and Two Women’s Inter Thompson Hall last Monday evening. of making plans for the coming year. Deliver Baccalaureate Sermon Sunday Morning in Men’s Gymnas — To Study Economic and Polit collegiate Contests— Tryouts Miss Marian Arthur, Manchester, The organization has some very in ium— Alumni Day Scheduled for Saturday— Week Ends ical Situation of Europe in September was elected vice-president; Elsworth teresting plans under way which will With Commencement Exercises Monday, June 14 D. -

As Heard on TV

Hugvísindasvið As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Janúar 2013 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Kt.: 080288-3369 Leiðbeinandi: Pétur Knútsson Janúar 2013 3 Abstract In this paper I research four grammar variables by watching three seasons of American television programs, aired during the winter of 2010-2011: How I Met Your Mother, Glee, and Grey’s Anatomy. For background on the history of prescriptive grammar, I discuss the grammarian Robert Lowth and his views on the English language in the 18th century in relation to the status of the language today. Some of the rules he described have become obsolete or were even considered more of a stylistic choice during the writing and editing of his book, A Short Introduction to English Grammar, so reviewing and revising prescriptive grammar is something that should be done regularly. The goal of this paper is to discover the status of the variables ―to lay‖ versus ―to lie,‖ ―who‖ versus ―whom,‖ ―X and I‖ versus ―X and me,‖ and ―may‖ versus ―might‖ in contemporary popular media, and thereby discern the validity of the prescriptive rules in everyday language. Every instance of each variable in the three programs was documented and attempted to be determined as correct or incorrect based on various rules. Based on the numbers gathered, the usage of three of the variables still conforms to prescriptive rules for the most part, while the word ―whom‖ has almost entirely yielded to ―who‖ when the objective is called for. -

Assessment of the Air Force Materiel Command Reorganization Report for Congress

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service INFRASTRUCTURE AND of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY Support RAND SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Purchase this document TERRORISM AND Browse Reports & Bookstore HOMELAND SECURITY Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Project AIR FORCE View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Research Report Assessment of the Air Force Materiel Command Reorganization Report for Congress Don Snyder, Bernard Fox, Kristin F. -

Tiger News 56

No 74 (F) Tiger Squadron Association February 2012 www.74squadron.org.uk Tiger News No 56 Compiled by Bob Cossey Association President Air Marshal Cliff Spink CB, CBE, FCMI, FRAeS Honorary Vice President Air Vice Marshal Boz Robinson FRAeS FCMI Association Chairman Gp Capt Dick Northcote OBE BA Association Treasurer Rhod Smart Association Secretary Bob Cossey BA (Hons) One of the many painted helmets worn by the Phantom crews at Wattisham. This one belonged to ‘Spikey’ Whitmore. Membership Matters New member Brian Jackson served at RAF Horsham St Faith with the squadron from October 1954 to April 1958. He held the rank of SAC as an armament mechanic. 74 was the only squadron with which Brian served. He recalls that whilst at St Faith he played trumpet in the band and thus attended many parades in Norwich and the surrounding area. He also followed his civvy trade of carpenter with a Sgt Halford who let Brian use a workshop on the station. Brian now lives in Australia. And new member Anthony Barber was an LAC (engine mechanic) on the squadron from May 1951-April 1953 on National Service. He was trained at Innsworth then posted to Bovingdon for three weeks before moving to Horsham St Faith where he stayed for the rest of his time. 1 th Cliff and the 74 Entry There is a story behind this photograph! Tony Merry of the 74th Entry Association explains. ‘During the Sunset Ceremony at the Triennial Reunion of the RAF Halton Apprentices Association in September 2010, a magnificent flying display was given by a Spitfire piloted by Cliff Spink. -

2Nd Air Division Memorial Library Film Catalogue

2nd Air Division 2nd Air Division Memorial Library Film Catalogue May 2015 2nd Air Division Memorial Library Film and Audio Collection Catalogue This catalogue lists the CDs, DVDs (section one) and videos (section two) in the Memorial Library’s film and audio collection. You can also find these listed in Norfolk Libraries online catalogue at http://www.norfolk.spydus.co.uk • Most items in the collection are not available for loan. • Films can be viewed in the Memorial Library Meeting Room during library opening hours (Mon to Sat 9am - 5pm). As the room can be booked for meetings, school visits etc, it is advisable to contact us in advance to book the room. • Films can be shown to groups and organisations by arrangement. Please contact the library for further details. 2nd Air Division Memorial Library The Forum Millennium Plain Norwich NR2 1AW Phone (01603) 774747 Email [email protected] . MEMORIAL LIBRARY CD S AND DVD S 1. “Troublemaker” A Pilot’s Story of World War II 466 th Bomb Group (Attlebridge) Robert W Harrington, B24 Pilot (2 copies) 2. Evade! Evasion Experiences of American Aircrews in World war II 54 minutes 3. D-Day to Berlin Acclaimed Film Maker’s World War II Chronicle 4. Cambridge American Cemetery & Memorial 5. My Heroes (445 th Bomb Group) 6. Tibenham – AAF Station 124: A Pictorial History 1943-1945 (445 th Bomb Group) Slides and sound files with word document: does not play on DVD player. Can be viewed on public PCs. (2 copies) 7. A Trip to Norwich Ret. Major John L Sullivan, Bombardier/Navigator, 93 rd BG (Hardwick) 2nd ADA’s 54 th Annual Convention in Norwich November 2001 (Contains archive footage of WWII) 1 hour (2 copies) 8. -

The Magazine of RAF 100 Group Association

. The magazine of RAF 100 Group Association 100 Group Association Chairman Wing Cdr John Stubbington: 01420 562722 100 Group Association Secretary Janine Harrington: 01723 512544 Email: [email protected] www.raf100groupassociation.org.uk Home to Memorabilia of RAF 100 Group Association City of Norwich Aviation Museum Old Norwich Road, Horsham St Faith, Norwich, Norfolk NR10 3JF Telephone: 01603 893080 www.cnam.co.uk Membership Areas Each dot represents an area where there is a cluster of members Big dots show where members of the RAF 100 Group Association Committee live Members who live abroad are in the following countries: Northern Ireland Canada Austria China Germany Australia USA South Africa Thailand Brazil New Zealand 2 Dear Friends A very happy New Year to you all! Thank you so much to everyone who sent cards and gifts and surprises to us over Christmas. There are far too many to mention you by name, but you know who you are, and I will say that each and every one was valued together with its sender. It really does show what a true Family we are. And there were so many lovely letters written by hand amongst them that I’m still catching up … so forgive me if you haven’t yet had a reply. I promise one is on its way! I also received a card from Horsham St Faith where, each year, we gather for the final event of our Reunion each year, a very special Service of Remembrance with a village tea to follow before saying our fond farewells. The card wished members on the Association a very Happy Christmas, and every happiness for the New Year.