RAF Wymeswold Part 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Library Additions BOOKS

Library Additions BOOKS GENERAL No12 Squadron during the Lincoln, Bristol Beaufighter, de ‘Sam’ Marshal of the refineries. S J Zaloga. Osprey Low Altitude Bombing System Havilland Mosquito/Vampire/ Royal Air Force The Lord Publishing, Kemp House, (LABS) weapons delivery Venom, English Electric/ Elworthy: a Biography. R Chawley Park, Cumnor Hill, trials among many other BAC Canberra/Strikemaster, Mead. Pen &Sword Aviation, Oxford OX2 9PH, UK. 2019. experiences recalled from a Gloster Meteor, Hawker Pen & Sword Books, 47 96pp. Illustrated. £14.99. ISBN flying career of over 45 years. Hunter/Sea Fury, Hunting Church Street, Barnsley, S 978-14728-3180-4. Percival Jet Provost, Short Yorkshire S70 2AS, UK. 2018. A very detailed analysis of Dorset Aviation Past and Sunderland/Sandringham, xiii; 330pp. Illustrated. £25. the operational effectiveness Present. Royal Aeronautical Supermarine Walrus and ISBN 978-1-52672-717-6. of the USAAF ‘Tidal Wave’ Society Christchurch Branch. SEPECAT Jaguar among A biography of the New mission of 1 August 1943 2016. 50pp. Illustrated. other aircraft types) that were Zealander Air Chief Marshal during WW2 which aimed A concise illustrated either sold to or operated in Sir Charles Elworthy MRAF to destroy strategically history of the development Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, (1911-1993) – subsequently important oil refineries in of aviation in Bournemouth, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, the Lord Elworthy – who, from Romania using Consolidated Poole, Portland, Weymouth, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay and initially joining the Reserve Air B-24D Liberators flown from Chickerell, Bridport, Toller, Venezuela and the British Force Officers in 1933, rose Benghazi in Libya. Upton, Moreton, Christchurch, colonies of British Guiana/ to being appointed both Chief Global Megatrends Swanage, Weymouth, Belize and the Falklands, of the Air Staff in September German Flak Defences and Aviation: the Warmwell, Tarrant Rushton Bolivia, Guatemala, Honduras, 1963 and also in 1967 Chief vs Allied Heavy Bombers Path To Future-Wise and Hurn. -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

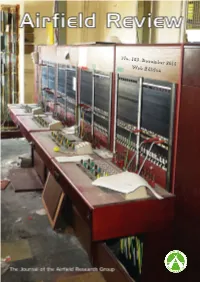

No. 153 December 2016 Web Edition

No. 153 December 2016 Web Edition Airfield Research Group Ltd Registered in England and Wales | Company Registration Number: 08931493 | Registered Charity Number: 1157924 Registered Office: 6 Renhold Road, Wilden, Bedford, MK44 2QA To advance the education of the general public by carrying out research into, and maintaining records of, military and civilian airfields and related infrastructure, both current and historic, anywhere in the world All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the author and copyright holder. Any information subsequently used must credit both the author and Airfield Review / ARG Ltd. T HE ARG MA N ag E M EN T TE am Directors Chairman Paul Francis [email protected] 07972 474368 Finance Director Norman Brice [email protected] Director Peter Howarth [email protected] 01234 771452 Director Noel Ryan [email protected] Company Secretary Peter Howarth [email protected] 01234 771452 Officers Membership Secretary & Roadshow Coordinator Jayne Wright [email protected] 0114 283 8049 Archive & Collections Manager Paul Bellamy [email protected] Visits Manager Laurie Kennard [email protected] 07970 160946 Health & Safety Officer Jeff Hawley [email protected] Media and PR Jeff Hawley [email protected] Airfield Review Editor Graham Crisp [email protected] 07970 745571 Roundup & Memorials Coordinator Peter Kirk [email protected] C ON T EN T S I NFO rmati ON A ND RE G UL ar S F E at U R ES Information and Notices .................................................1 AW Hawksley Ltd and the Factory at Brockworth ..... -

Raaf Personnel Serving on Attachment in Royal Air Force Squadrons and Support Units in World War 2 and Missing with No Known Grave

Cover Design by: 121Creative Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6012 email. [email protected] www.121creative.com.au Printed by: Kwik Kopy Canberra Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6066 email. [email protected] www.canberra.kwikkopy.com.au Compilation Alan Storr 2006 The information appearing in this compilation is derived from the collections of the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia. Author : Alan Storr Alan was born in Melbourne Australia in 1921. He joined the RAAF in October 1941 and served in the Pacific theatre of war. He was an Observer and did a tour of operations with No 7 Squadron RAAF (Beauforts), and later was Flight Navigation Officer of No 201 Flight RAAF (Liberators). He was discharged Flight Lieutenant in February 1946. He has spent most of his Public Service working life in Canberra – first arriving in the National Capital in 1938. He held senior positions in the Department of Air (First Assistant Secretary) and the Department of Defence (Senior Assistant Secretary), and retired from the public service in 1975. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree (Melbourne University) and was a graduate of the Australian Staff College, ‘Manyung’, Mt Eliza, Victoria. He has been a volunteer at the Australian War Memorial for 21 years doing research into aircraft relics held at the AWM, and more recently research work into RAAF World War 2 fatalities. He has written and published eight books on RAAF fatalities in the eight RAAF Squadrons serving in RAF Bomber Command in WW2. -

RAF Wymeswold Part 3

Part Three 1956 to 1957 RAF Wymeswold– Postwar Flying 1948 to 1970 (with a Second World War postscript) RichardKnight text © RichardKnight 2019–20 illustrations © as credited 2019–20 The moral rights of the author and illustrators have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the author, except for brief passages quoted in reviews. Published as six downloadablePDFfiles only by the author in conjunction with the WoldsHistorical Organisation 2020. This is the history of an aerodrome, not an official document. It has been drawn from memories and formal records and should give a reliable picture of what took place. Any discrepancies are my responsibility. RichardKnight [email protected]. Abbreviations used for Royal Air Force ranks PltOff Pilot Officer FgOff Flying Officer FltLt Flight Lieutenant SqnLdr Squadron Leader WgCdr Wing Commander GpCapt Group Captain A Cdr Air Commodore Contents This account of RAF Wymeswoldis published as six free-to-downloadPDFs. All the necessary links are at www.hoap/who#raf Part One 1946 to 1954 Farewell Dakotas; 504 Sqn.Spitfires to Meteors Part Two 1954 to 1955 Rolls Roycetest fleet and sonic bangs; 504 Sqn.Meteors; RAFAAir Display; 56 SqnHunters Part Three 1956 to 1957 The WymeswoldWing (504 Sqn& 616 SqnMeteors); The WattishamWing (257 Sqn& 263 SqnHunters); Battle of Britain ‘At Home’ Part Four Memories from members of 504 Sqn On the ground and in the air Part Five 1958 to 1970 Field Aircraft Services: civilian & military aircraft; No. 2 Flying Training School; Provosts & Jet Provosts Part Six 1944 FrederickDixon’simages: of accommodation, Wellingtons, Hampdens, Horsasand C47s Videos There are several videos about RAF Wymeswold, four by RichardKnight:, and one by Cerrighedd: youtu.be/lto9rs86ZkY youtu.be/S6rN9nWrQpI youtu.be/7yj9Qb4Qjgo youtu.be/dkNnEV4QLwc www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTlMQkKvPkI You can try copy-and-pasting these URLsinto your browser. -

Police and Fire Uniform Contract to Allie Brothers

CITY of NOVI CITY COUNCIL Agenda Item D May 7, 2018 SUBJECT: Approval to award contract for Pollee and fire Department uniforms to Allie Brothers, Inc. , the lowest responsive and responsible bidder, for an esHmated annual amount of $90,000 for a period of two (2) years, with three (3) renewal options In one (1) year Increments. SUBMITIING DEPARTMENT: Public Safe t¥~ CITY MANAGER APPROVAL: EXPENDITURE REQUIRED Estimated $90,000 AMOUNT BUDGETED $167,000 (Includes tum-out gear, ballistic vests, cleaning and other Hems} APPROPRIATION REQUIRED N/A LINE ITEM NUMBER 101-301.00-741.000, 101-337.00-741.000 BACKGROUND INFORMATION: The bid documents were posted on the Michigan Intergovernmental Trade Network (MITN) website on March 20. 2018 and email notifications were sent to 93 firms. We received four (4) bids with unit pricing. Allie Brothers was the only vendor that bid on all the items and had the lowest unit pricing on the majority of items. This contract provides all uniforms required by the Police and Fire Departments. Police and Fire officers are provided a full uniform at hiring. Thereafter, replacements are ordered based upon yearly summer and winter uniform inspections. This is a two (2) year contract with three (3) renewal options in one ( 1) year increments. RECOMMENDED ACTION: Approval to award contract for Pollee and fire Department uniforms to Allie Brothers, Inc. the lowest responsive and responsible bidder, for an estimated annual amount of $90,000 for a period of two (2) years, with three (3) renewal options In one (1) year increments. CITY OF NOVI APRIL 11,2018 UNIFORMS BID- POLICE DEPARTMENT Phoenix Safety Michigan Police Brand I Model # Additional Description Allie Brothers Nye Uniform POLICE Outfitters Equipment Shirts . -

Tiger News 56

No 74 (F) Tiger Squadron Association February 2012 www.74squadron.org.uk Tiger News No 56 Compiled by Bob Cossey Association President Air Marshal Cliff Spink CB, CBE, FCMI, FRAeS Honorary Vice President Air Vice Marshal Boz Robinson FRAeS FCMI Association Chairman Gp Capt Dick Northcote OBE BA Association Treasurer Rhod Smart Association Secretary Bob Cossey BA (Hons) One of the many painted helmets worn by the Phantom crews at Wattisham. This one belonged to ‘Spikey’ Whitmore. Membership Matters New member Brian Jackson served at RAF Horsham St Faith with the squadron from October 1954 to April 1958. He held the rank of SAC as an armament mechanic. 74 was the only squadron with which Brian served. He recalls that whilst at St Faith he played trumpet in the band and thus attended many parades in Norwich and the surrounding area. He also followed his civvy trade of carpenter with a Sgt Halford who let Brian use a workshop on the station. Brian now lives in Australia. And new member Anthony Barber was an LAC (engine mechanic) on the squadron from May 1951-April 1953 on National Service. He was trained at Innsworth then posted to Bovingdon for three weeks before moving to Horsham St Faith where he stayed for the rest of his time. 1 th Cliff and the 74 Entry There is a story behind this photograph! Tony Merry of the 74th Entry Association explains. ‘During the Sunset Ceremony at the Triennial Reunion of the RAF Halton Apprentices Association in September 2010, a magnificent flying display was given by a Spitfire piloted by Cliff Spink. -

May | June 2018

May | June 2018 GRAY WING ELECTRIC ABSTRACTIONS Through June 10 Jayne Behman, mm13 Daniel Leighton, Permission to Enter Robert Chapman, Z-89 (detail) Electric Abstractions focuses on three California artists using computer technology to create contemporary fine art. Daniel Leighton, Robert Chapman, and Jayne Behman have been creating images digitally for years—drawing with digits and painting with pixels. Jayne Behman and Robert Chapman both have had formal training and years of experience and backgrounds in traditional studio art. Their forays into digital art started after they had already established themselves as artists. “For SLOMA, this is an opportunity to embrace new media, celebrate three artistic talents with visually compelling artwork, and present an exhibition that also appeals to younger audiences,” said Ruta Saliklis, SLOMA curator. To mark the exhibition’s closing, SLOMA presents pianist and multi-media artist Josh Nelson for a special performance in the Gray Wing pn Sunday, June 10 at 5 PM. Tickets $20 general seating. u SELECTIONS: BAY AREA June 15 to August 19 SLOMA is showcasing the mysterious oil paintings by Anne Subercaseaux and the magically woven metal sculptures by Flora Davis in Selections: Bay Area. When Ruta Saliklis, curator, viewed the shared mystery and alchemy inherent in the artwork by these two artists from the San Francisco Bay Area, it was all she needed to envision the next exhibition in her Selections series— exhibitions featuring the harmonious and well-matched grouping of important artists from a selected region. Anne Subercaseaux finds substance in the insubstantial, in paintings that freeze the ephemeral patterns of reflection and shadow. -

The Magazine of RAF 100 Group Association

. The magazine of RAF 100 Group Association 100 Group Association Chairman Wing Cdr John Stubbington: 01420 562722 100 Group Association Secretary Janine Harrington: 01723 512544 Email: [email protected] www.raf100groupassociation.org.uk Home to Memorabilia of RAF 100 Group Association City of Norwich Aviation Museum Old Norwich Road, Horsham St Faith, Norwich, Norfolk NR10 3JF Telephone: 01603 893080 www.cnam.co.uk Membership Areas Each dot represents an area where there is a cluster of members Big dots show where members of the RAF 100 Group Association Committee live Members who live abroad are in the following countries: Northern Ireland Canada Austria China Germany Australia USA South Africa Thailand Brazil New Zealand 2 Dear Friends A very happy New Year to you all! Thank you so much to everyone who sent cards and gifts and surprises to us over Christmas. There are far too many to mention you by name, but you know who you are, and I will say that each and every one was valued together with its sender. It really does show what a true Family we are. And there were so many lovely letters written by hand amongst them that I’m still catching up … so forgive me if you haven’t yet had a reply. I promise one is on its way! I also received a card from Horsham St Faith where, each year, we gather for the final event of our Reunion each year, a very special Service of Remembrance with a village tea to follow before saying our fond farewells. The card wished members on the Association a very Happy Christmas, and every happiness for the New Year. -

To Let Hangers

TO LET NEWTON . NOTTINGHAMSHIRE . NG30 8HL newton FORTY SIX BUSINESS PARK BIG, DRY, SECURE STORAGE SPACE, AVAILABLE NOW! HANGERS from 4,510M (48,547FT2) to 24,779M (266,706FT2) IMMEDIATELY AVAILABLE SHORT TERM LICENSES TO LONG TERM LEASES 24 HOUR SITE SECURITY CLEAR SPAN SPACE – 9.3M EAVES BACKGROUND ACCOMMODATION Recently acquired by our clients who specialise in the active management and Available individually or combined we can offer: development of Former Ministry of Defence bases, we are delighted to offer space at Newton 46 – the former RAF Newton Airbase. SCHEDULE OF AREAS Offering a unique opportunity, we can offer a huge range of premises from small self 2 2 newton contained production units to quality refurbished offices and enormous hangars. Unit sq m sq ft FORTY SIX Hanger1 5,063 54,495 BUSINESS PARK All available immediately on flexible terms from a matter of months to any number of years. LOCATION Hanger2 5,073 54,606 Newton 46 is set to the east of Nottingham just off the A46 which links Newark Hanger3 5,067 54,534 to Leicester and is also adjacent to the A52 which links the A1 trunk road to Nottingham City Centre and the M1 Motorway in turn. Hanger4 5,066 54,524 The precise location is detailed on the adjacent plans. Hanger5 4,510 48,547 THE PROPERTIES Total GIA 24,779 266,706 The five hangars available individually or combined offer unique space. With extensive hard surfacing offering terrific lorry parking and/or car parking, (These areas are given for information purposes only and prospective this space can also be used for secure external storage. -

Last Flight of Beauforts L.9943, L.9829 & L

2021 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. Bristol Beaufort Mk. I X.8931 L2 No. 5 (Coastal) Operational Training Unit Courtesy of North Devon Athenaeum THE LAST FLIGHT OF: BEAUFORTS L.9943, L.9829, L.9858 A narrative of the last flights of Beaufort L.9943, which crashed near R.A.F. Chivenor on the night of 19 December 1940, killing the pilot, Sgt J. BLATCHFORD and severely injuring the air gunner; Beaufort L.9829 which crashed on 18 February 1941, mortally wounding the Australian pilot, Sgt A. H. S. EVANS, and Beaufort L.9858, which crashed on 24 February 1941, killing the South African pilot, P/O H. MUNDY. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2021) 4 May 2021 [LAST FLIGHT OF BEAUFORTS L.9943, L.9829 & L.9858] The Last Flight of Beaufort L.9943, L.9829 & L.9858 Version: V3_4 This edition dated: 4 May 2021 ISBN: Not yet allocated. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means including: electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, scanning without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. (copyright held by author) Research & Assistance: Stephen HEAL, David HOWELLS & Graham MOORE Published privately by: The Author – Publishing as: www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk The author wishes to thank the niece of James BLATCHFORD, Kate DODD; and the daughter of Roy WATLING-GREENWOOD, Ann, for their support and assistance in providing information and photographs for inclusion in this booklet. Without them, the story of these two remarkable men would not be complete. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana