Effects of Inlet Migration on Barrier Island Planform and Oceanfront Change: New Topsail Inlet, N.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NORTH CAROLINA NOVELS the Coast

NORTH CAROLINA NOVELS The Coast The River to Pickle Beach (1972) Betts, Doris In the summer of 1968, Jack and Bebe Sellars take over the management of Pickle Beach on the NC coast. They hope for a peaceful summer but the arrival of several difficult people including a violent, racist former Army buddy of Jack’s the peace is disrupted. Cape Fear Murders (2003) Canada, Wanda Carroll Davenport, a local developer who has an unlucky habit of getting drawn into murder investigations, is back on the case when she finds NC State Senator William Burriss III murdered alongside hiss mistress. Carroll chases criminals all over Wilmington and Wrightsville Beach in this sequel to Island Murders. Island Murders (2001) Canada, Wanda Carroll Davenport is the first suspect when bodies begin showing up all over Figure Eight Island, an exclusive resort community near Wilmington. Carroll is soon cleared and decides to solve the case on her own. Storm Warriors (2001) (JFic) Carbone, Elisa L. Nathan Williams lives on Pea Island with his grandfather in 1895. Nathan is fascinated by the “surfmen,” the African American rescue crew at the United States Life-Saving Station. Nathan dreams of joining them and spends all of his free time observing the surfmen and studying their books. Her mother’s Shadow (2004) Chamberlain, Diane Lacey O’Neill grew up in a small community on the Outer Banks. She has always tried to live up to the memory of her mother who was murdered when Lacey was thirteen. Lacey, now in her mid-twenties is suddenly thrust into the role of mother when she becomes guardian of Mackenzie, the daughter of Lacey’s best friend who was killed in an automobile accident. -

Bibliography of North Carolina Underwater Archaeology

i BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH CAROLINA UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY Compiled by Barbara Lynn Brooks, Ann M. Merriman, Madeline P. Spencer, and Mark Wilde-Ramsing Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Division of Archives and History April 2009 ii FOREWARD In the forty-five years since the salvage of the Modern Greece, an event that marks the beginning of underwater archaeology in North Carolina, there has been a steady growth in efforts to document the state’s maritime history through underwater research. Nearly two dozen professionals and technicians are now employed at the North Carolina Underwater Archaeology Branch (N.C. UAB), the North Carolina Maritime Museum (NCMM), the Wilmington District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE), and East Carolina University’s (ECU) Program in Maritime Studies. Several North Carolina companies are currently involved in conducting underwater archaeological surveys, site assessments, and excavations for environmental review purposes and a number of individuals and groups are conducting ship search and recovery operations under the UAB permit system. The results of these activities can be found in the pages that follow. They contain report references for all projects involving the location and documentation of physical remains pertaining to cultural activities within North Carolina waters. Each reference is organized by the location within which the reported investigation took place. The Bibliography is divided into two geographical sections: Region and Body of Water. The Region section encompasses studies that are non-specific and cover broad areas or areas lying outside the state's three-mile limit, for example Cape Hatteras Area. The Body of Water section contains references organized by defined geographic areas. -

State of the Coast Report 2009

NORTH CAROLINA COASTAL FEDERATION State of the COAST Report 2009 THE FUTURE OF OUR BEACHES State of the COAST North Carolina has some of the most valuable places. As the buffer is eaten away by erosion and a general shortage and sometimes mismanagement of sand in the system, public and private NCCF is a non-profit tax-exempt organization dedicated and beautiful beaches in the world. In this State of to involving citizens in decisions about managing coastal oceanfront property owners have become increasingly concerned about their the Coast Report, we examine what needs to be investments. resources. Its aim is to share technical information and done to protect them. resources to better represent current and long-term Rising sea level will make oceanfront management decisions even more economic, social and environmental interests of the North In writing this report, we looked beyond current arguments over challenging in the future. Previous predictions of the range of sea level rise Carolina Coast. whether to maintain the state’s ban on seawalls, jetties and groins. Let’s be were based on limited scientific knowledge and focused on the oceans ability very clear–the federation is on the forefront of efforts to keep this ban in to absorb heat. These measurements are now being refined by new federal NCCF BOARD OF DIRECTORS place. But we also recognize that the fight to keep the state’s ban on hard research that indicates that a three-foot rise in sea level over the next 90 President Melvin Shepard, Jr. – Sneads Ferry structures to control erosion is only a symptom of a much larger and more years that can be expected along our coast. -

North Carolina Architecture

2016 Directory North Carolina Architecture 2016-2017 AIA North Carolina Directory 3 Home Elevator Incline Platform Lift Vertical Platform Lift LULA Elevator Designing a more accessible world. Port City Elevator, Inc. installs and services residential and light commercial elevators, dumbwaiters, Stairlifts, Platform lifts, and other accessibility equipment. As a licensed and insured provider, we bring over 20 years of combined experience in working with architects, general contractors, home owners, and planners to ensure the right product is installed to meet your needs. We are dedicated to the results that you, our customer, expect. Port City Elevator, Inc. is committed to its customers, to its people, and to the leading manufacturers that partner with us. Authorized Garaventa Lift Representative (910)2016-2017 790-9300 AIA North Carolina Directory| 3334 US Hwy 421 North, Ste B • Wilmington, NC 28401 | www.portcityelevator.com 5 2016 Directory North Carolina Architecture ON THE COVER: 2015 Honor Award Winner Robeson County Department of Social Services. Photo credit: 2015, Mark Herboth Photography Contents ASSOCIATION INFORMATION EDUCATION 9 About the American Institute of Architects 152 Continuing Education Mandatory for Licensure and Membership 2016 LEADERSHIP 153 Architectural Education 10 2016 AIA North Carolina President’s Message 13 2016 Leadership BOARD & COMMITTEES 18 AIA North Carolina Staff 154 N.C. Board of Architecture 154 National Council of Architectural Registration Boards MEMBERSHIP INFORMATION 155 AIA Political Action -

North Carolina Power

NORTH CAROLINA electing North Carolina’s most influential business leaders could be as complex as counting sand crystals at the beach, but it’s a lot more fun. No one expects the list to be “right,” because influence is subjective and the state business community is packed with so many powerful people. But this best effort stems from gathering ideas from dozens of businesspeople across the state and rely- ing on our staff’s collective knowledge based on many years working in North Carolina. Our goal is to cite influential folks who are making a significant impact in their Senterprises, industries and, in many cases, the broader community. We omitted political lead- ers and those who spend very little time here. We also sought individuals who often operate behind the scenes and avoid publicity. Gathering information about these leaders gives us a renewed respect for the dynamism of North Carolina’s economy. The state benefits from rapid growth in its largest metro areas, abundant natural resources and an unmistakable pro-business attitude. The list includes a mix of people who are second-, third- and even fourth-generation family-business leaders (Frank Harrison III, David Congdon) and newcomers who’ve built cutting-edge operations from scratch (Michael Praeger, Doug Lebda). Reflecting our mission as a statewide business publication, we looked for leaders making important strides outside the three large metropolitan areas. While we found impactful lead- ers in smaller regions, power is increasingly concentrated in bigger cities as banking, retailing, utilities and other industries consolidate. We look forward to hearing your thoughts. -

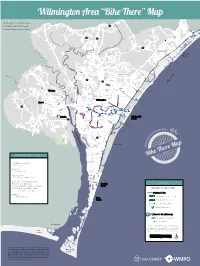

Bike There Map Final 16.5 by 22 for Print Copy

Wilmington Area “Bike �ere” Map Wilmington Urban Area Metropolitan Planning 210 Organization boundary Clarks Landing Rd Cheshire Rd Hampstead 17 Kiwanis Blueberry Rd 133 Park 117 Sloop Point Loop Rd S Belvedere Dr Country Club Dr Hoover Rd Olde Point Rd 210 Peanut Rd Hampstead Island Creek Rd Factory Rd Topsail Holly Shelter Rd Beach Washington Acres Rd Cowpen Landing Rd New Topsail Inlet Blue Clay Rd Sidbury Rd 140 Scotts Hill Loop Rd JOHN J BURNEY FWY Northwest Rd NE Mt Misery Rd NE Rock Hill Rd reek R Northwest Rd NE 40 h C d tc u Olsen F 133 Park Murrayville Rd 17 Rich Inlet 132 P Marsh O orters Ne a ck Cedar Hill Rd NE ks E R Atlantic Ocean Dr d d N Kerr Ave g e Smith Creek Torchwood Blvd w a Park MARKET ST t e r White Rd C lu Harris Rd b Rd 140 421 Farington Farms Rd Ogden Blue Clay Rd N Kerr Ave Gordon Rd ANDREW JACKSON HWY Castle Hayne Rd Ogden Navassa Park Figure Eight Island Lincoln Rd Middle Sound Loop Rd r D l o w Wood Sorrell Rd Malmo Loop Rd h MeadowsGreen Grat Lord Tennyson Rd Station Rd Old Mill Rd MARTIN 74 76 Archie LUTHER KING JR PKY Blue St Northwest Park St rd District Park th Maides 23 MARTIN 30 Park MARKET ST Malmo Loop Rd St th Wilmington Village Rd Princess Place Dr New Centre Mason Inlet N 11 Colon Mintz Rd NE Maco Rd NE Chestnut St Eastwood Rd Leland S Navassa Rd Market St Kerr Ave Old Fayetteville Rd Military Cuto Rd Wallace Park Racine Dr S Fifth Ave S Third St S Front St Robert Metts Ave d Strange Randall Pkwy R e Lumina Ave arv l H e Park l 87 Pine s McCrary i v t Park s D B r UNCW e L r Wooster St S COLLEGE -

Amicus Brief

NO. 409PA15 THIRD DISTRICT ******************************************************** SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA ******************************************************** GREGORY P. NIES and DIANE S. ) NIES, ) ) Plaintiff-Petitioners, ) ) v. ) ) TOWN OF EMERALD ISLE, a North ) Carolina Municipality, ) ) Defendant-Respondent. ) ************************** BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE GRAHAM KENAN PROFESSOR OF LAW EMERITUS JOSEPH KALO, THE NORTH CAROLINA ASSOCIATION OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS, THE NORTH CAROLINA BEACH, INLET & WATERWAY ASSOCIATION, THE COUNTIES OF BRUNSWICK, CARTERET, NEW HANOVER, ONSLOW, AND PENDER, NORTH CAROLINA, THE TOWNS OF ATLANTIC BEACH, CAROLINA BEACH, CASWELL BEACH, HOLDEN BEACH, INDIAN BEACH, KURE BEACH, NORTH TOPSAIL BEACH, OAK ISLAND, OCEAN ISLE BEACH, PINE KNOLL SHORES, SUNSET BEACH, SURF CITY, TOPSAIL BEACH, AND WRIGHTSVILLE BEACH, NORTH CAROLINA, AND THE VILLAGE OF BALD HEAD ISLAND, NORTH CAROLINA ************************** - i - TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 1 INTEREST OF AMICI .............................................................. 3 A. Joseph Kalo, Graham Kenan Professor of Law Emeritus ......................................................... 3 B. North Carolina Association of County Commissioners ....................................................... 4 C. North Carolina Beach, Inlet & Waterway Association ............................................................. 4 D. Southern Coastal Local Governments ................... 5 -

RICKY DAVIS (All Dates Fall 1995) RED

IES O E IES RICKY DAVIS (All Dates Fall 1995) RED-THROATED LOON: Inland reports included singles at Falls Lake near Raleigh, NC Nov. 12 (Ricky Davis) and Nov. 25 (Harry LeGrand); and at Lake Norman near Charlotte, NC late Nov. into December (David Wright). PIED-BILLED GREBE: One found near Glen Ayre, Mitchell Co., NC Sept. 18 was at a relatively high elevation (3200') for the species (Rick Knight). HORNED GREBE: There was an impressive movement of this species in the Raleigh area in late November when on the 25th, 100+ were on Falls Lake (Harry LeGrand) and 110 were counted at Jordan Lake (Will Cook)! EARED GREBE: The Sumter, SC birds returned by Sept. 11 (Lex Glover, Evelyn Dabbs, Chris Eley) and the Goldsboro, NC birds returned by Aug. 5 (Eric Dean). The peak at Goldsboro was eight on Sept. 26 and up to five remained through the period (Dean). Also of interest was one at the Savannah Spoil Site, Jasper Co., SC on Nov. 8 (Steve Calver). RED-NECKED GREBE: The only fall report was of the single bird found on Lake Norman Nov. 13 (David Wright). NORTHERN FULMAR: One was found sick in the surf (and later died) on N. Core Banks, NC on the amazing date of Aug. 11 (Gerald Weaver, fide Trip Dennis)! BLACK-CAPPED PETREL: This species was present offshore in good numbers this season with the peak count being 192 off Hatteras, NC Aug. 6 (Brian Patteson, et al.). HERALD PETREL: This species was found twice this season with one dark phase bird Aug. -

World War II Heritage Guide Map Rented Rooms to Soldiers and War Workers, and Blackouts

outs and dim-outs. German U-boats marauding and a crime wave, and apply equal justice. W IlMINgtoN at War offshore spilled debris from sunken Allied ships Citizens became volunteer airplane spotters, Southeastern North Carolina was a mighty on favorite bathing beaches. Until 1944, the Inland Waterway boat patrollers, air raid war- contributor to the U.S. war effort in World War orld ar threat remained of German attack by sea and air. dens and auxiliary police and firemen. Women W W II II. Wilmington was called “The Defense Capital The community coped with a dire housing short- excelled in the Aircraft Warning Service, war of the State” and became the country’s unique age, and strains on schools, transportation, med- wartime boomtown. The once-quiet city, geo- bond and scrap drives, and as Red Cross nurse's ical and social services, law enforcement, food aides. All of this was undertaken into 1944 graphically isolated for decades, suddenly found supply, security and entertainment. Families erItage through continuing low-light dim-outs and beach H itself an exploding center of military life and World War II Heritage Guide Map rented rooms to soldiers and war workers, and blackouts. defense production. historic houses were cut up into apartments. Each branch of the armed forces stationed Racially segregated entertainment and social of and The population more than doubled with the life proceeded, despite rationing of gasoline, Wilmington thousands in the area ---- the Army Air Forces at influx of military personnel, war workers and uIde ap tires, sugar, coffee, and whiskey. Front Street, Southeastern North Carolina g M the airport, the Army at Camp Davis and Fort their families. -

Coastal Erosion Study

Coastal Erosion Study Division of Coastal Management North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality February 12, 2016 N.C. Division of Coastal Management, 400 Commerce Avenue, Morehead City, N.C. 28557 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.0 Beach Erosion ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 The Natural System .......................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Human Influences ............................................................................................................................. 13 2.0 Historical Shoreline Change ................................................................................................................. 16 2.1 North Carolina’s Erosion Studies ..................................................................................................... 16 2.2 Long‐Term vs. Short‐Term Studies ................................................................................................... 17 2.3 Regional Variation ........................................................................................................................... -

Overview of Oceanfront Shorelines: Cape Lookout to Sunset Beach, NC

Overview of Oceanfront Shorelines: Cape Lookout to Sunset Beach, NC Prepared By William J. Cleary Prepared for Moffat & Nichol August 8, 2008 Overview of Oceanfront Shorelines: Cape Lookout to Sunset Beach, NC By William J. Cleary NORTH CAROLINA COASTAL SETTING A map of the NC coastal system reflects major differences in the geological heritage derived from the underlying geological framework (Riggs et al., 1995). Cape Lookout separates the 336 mile long coastline into two distinct provinces (Fig. 1). Each province has a unique geologic framework that results in distinctive types of coastal features. The northern province is underlain primarily by unconsolidated sediments of Quaternary age that thicken northward to fill the Albemarle Embayment with up to 230 ft of material. The low-lying coastal area that has evolved along this gentle depositional surface consists of wide shallow bays fronted by long narrow barriers. A few hardbottoms of Pleistocene age are found scattered across the shoreface (Riggs et al., 1992, 1995; Boss and Hoffman, 1999). In contrast, the coastal system in the southern province, from Cape Lookout (Figs. 1 and 2) south to the South Carolina border, is underlain by rock units that range in age from the Upper Cretaceous through the Pleistocene (Meisburger, 1977 and 1979; Snyder et al., 1982; Snyder et al., 1994 and Cleary et al., 1996). In this region, only a thin and highly variable veneer of sediments of Quaternary age is preserved. The underlying units are associated with the Carolina Platform that underlies the region between Myrtle Beach, SC and Cape Fear, NC. This structural platform has risen slightly causing the units to dip to the north and east, causing them to be truncated by the shoreline and the shoreface. -

Interview with George H. Mceachern, February 13, 2007

University of North Carolina Wilmington Archives and Special Collections Interview with George H. McEachern, February 13, 2007 Title: Interview with George H. McEachern, February 13, 2007 Date: February 13, 2007 Description: Interview with George McEachern, whose family has been part of the local business community for several generations and whose ventures have included a Coca-Cola bottling plant and investment in real estate. Repository: UNCW Archives and Special Collections Transcript: Interviewee: McEachern, George Interviewer: Jones, Carroll Date of Interview: 2/13/2007 Series: SENC Notables Length 120 minutes Jones: Good afternoon. Today is Tuesday, February 13, 2007 and I'm Carroll Jones with Matt Early for the Randall Library Special Collection Oral History Program. We've very pleased today to be speaking with Wilmington native, George McEachern, whose family has been not only a part of the business community for several generations, but most generous benefactors in multiple areas. Thank you for visiting, George. McEachern: It's a pleasure to be here and I thank you for the opportunity of letting me talk a little bit about the family and about Wilmington. Jones: Oh I can hardly wait! You can start anywhere you want, but maybe you could go back a few years and tell us how your family, the Hutaff's and the McEachern's and so forth came to Wilmington, and what businesses they were in originally and how this developed. McEachern: Okay. I'd be glad to do that. I'm not familiar with the Hutaff side of the family, primarily Interview with George H. McEachern, February 13, 2007 Page 1 University of North Carolina Wilmington Archives and Special Collections because my grandfather on the McEachern side of the family had passed away before I was born, so I just heard about him in stories.