Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Currently Sir Frederick Ballantyne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Department of Political Science Westfield

ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE WESTFIELD, ALWYN W BA. HONORS UNIVERSITY OF ESSEX, 1976 MS. LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, 1977 THE IMPACT OF LEADERSHIP ON POLITICS AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN ST VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES UNDER EBENEZER THEODORE JOSHUA AND ROBERT MILTON CATO Committee Chair: Dr. F.SJ. Ledgister Dissertation dated May 2012 This study examines the contributions of Joshua and Cato as government and opposition political leaders in the politics and political development of SVG. Checklist of variable of political development is used to ensure objectivity. Various theories of leadership and political development are highlighted. The researcher found that these theories cannot fully explain the conditions existing in small island nations like SVG. SVG is among the few nations which went through stages of transition from colonialism to associate statehood, to independence. This had significant effect on the people and particularly the leaders who inherited a bankrupt country with limited resources and 1 persistent civil disobedience. With regards to political development, the mass of the population saw this as some sort of salvation for fulfillment of their hopes and aspirations. Joshua and Cato led the country for over thirty years. In that period, they have significantly changed the country both in positive and negative directions. These leaders made promises of a better tomorrow if their followers are prepared to make sacrifices. The people obliged with sacrifices, only to become disillusioned because they have not witnessed the promised salvation. The conclusions drawn from the findings suggest that in the process of competing for political power, these leaders have created a series of social ills in SVG. -

2013 Budget Speech

BUILDING A SUSTAINABLE, RESILIENT ECONOMY IN CHALLENGING TIMES BY DR. THE HON. RALPH E. GONSALVES PRIME MINISTER OF ST. VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES INTRODUCTION Mr. Speaker, Honourable Members, since our country’s attainment of independence on October 27, 1979, there have been 33 annual budgets. Robert Milton Cato, of blessed memory, crafted four of these budgets; Sir James Mitchell fashioned fourteen; Arnhim Eustace delivered three; and Budget 2013 is the twelfth which I am presenting. Each Minister of Finance has sought to make St. Vincent and the Grenadines a better place for its citizens; and to a greater or lesser extent each has succeeded despite the inherent limitations of our vulnerable small, multi-island economy and the awesome external challenges which confront us. Each national Budget has had its own peculiar or special frame against the backdrop of the general socio-economic condition. Each national Budget, too, is required to have its own focus, coherence, and developmental thrust. Each Budget is necessarily a house-keeping and developmental exercise, but much takes place, too, in the economy outside the Budget’s structured frame. For convenience, each possesses its own theme. For Budget 2013, the overarching theme is simple, yet profound: Building a Sustainable, Resilient Economy in Challenging Times. Mr. Speaker, it is inescapable that a Budget, especially in its developmental as distinct from its routine house-keeping function, is shaped by the Government’s thinking, explicit or implicit, in respect of the appropriate or relevant praxis – theory and practice – of economic development for micro-economies such as St. Vincent and the Grenadines. -

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines INTRODUCTION located on Saint Vincent, Bequia, Canouan, Mustique, and Union Island. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is a multi-island Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, like most of state in the Eastern Caribbean. The islands have a the English-speaking Caribbean, has a British combined land area of 389 km2. Saint Vincent, with colonial past. The country gained independence in an area of 344 km2, is the largest island (1). The 1979, but continues to operate under a Westminster- Grenadines include 7 inhabited islands and 23 style parliamentary democracy. It is politically stable uninhabited cays and islets. All the islands are and elections are held every five years, the most accessible by sea transport. Airport facilities are recent in December 2010. Christianity is the Health in the Americas, 2012 Edition: Country Volume N ’ Pan American Health Organization, 2012 HEALTH IN THE AMERICAS, 2012 N COUNTRY VOLUME dominant religion, and the official language is fairly constant at 2.1–2.2 per woman. The crude English (1). death rate also remained constant at between 70 and In 2001 the population of Saint Vincent and 80 per 10,000 population (4). Saint Vincent and the the Grenadines was 102,631. In 2006, the estimated Grenadines has experienced fluctuations in its population was 100,271 and in 2009, it was 101,016, population over the past 20 years as a result of a decrease of 1,615 (1.6%) with respect to 2001. The emigration. According to the CIA World Factbook, sex distribution of the population in 2009 was almost the net migration rate in 2008 was estimated at 7.56 even, with males accounting for 50.5% (50,983) and migrants per 1,000 population (5). -

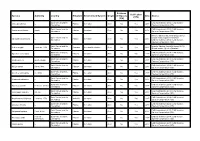

GRIIS Records of Verified Introduced and Invasive Species

Evidence Verification Species Authority Country Kingdom Environment/System Origin of Impacts Date Source (Y/N) (Y/N) Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Abrus precatorius L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Acacia auriculiformis Benth. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Invasive Species Specialist Group (2015). Saint Vincent and the Global Invasive Species Database. Adenanthera pavonina L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the Invasive Species Specialist Group (2015). Aedes aegypti Linnaeus, 1762 Animalia terrestrial/freshwater Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Global Invasive Species Database. Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Ageratum conyzoides L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Albizia procera Benth. (Roxb.) Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Albizia saman (Jacq.) Merr. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Aleurites moluccanus (L.) Willd. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Allamanda cathartica L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Alpinia purpurata K.Schum. (Vieill.) Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). -

SAINT VINCENT and the GRENADINES Pilot Program For

SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES PPCR PHASE 1 PROPOSAL SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR) PHASE ONE PROPOSAL 1 SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES PPCR PHASE 1 PROPOSAL Contents Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations .................................................................................. 5 Summary of Phase 1 Grant Proposal ................................................................................... 7 1.0 PROJECT BACKGROUND....................................................................................... 10 1.1 National Overview .................................................................................................. 11 1.1.1. Country Context ......................................................................................................... 11 2.0. Vulnerability Context .................................................................................................. 14 2.1 Climate .................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1 Precipitation ............................................................................................................... 14 2.1.2 Temperature ................................................................................................................ 15 2.1.3 Sea Level Rise ............................................................................................................. 15 2.1.4 Climate Extremes ....................................................................................................... -

The University of Chicago the Creole Archipelago

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CREOLE ARCHIPELAGO: COLONIZATION, EXPERIMENTATION, AND COMMUNITY IN THE SOUTHERN CARIBBEAN, C. 1700-1796 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TESSA MURPHY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2016 Table of Contents List of Tables …iii List of Maps …iv Dissertation Abstract …v Acknowledgements …x PART I Introduction …1 1. Creating the Creole Archipelago: The Settlement of the Southern Caribbean, 1650-1760...20 PART II 2. Colonizing the Caribbean Frontier, 1763-1773 …71 3. Accommodating Local Knowledge: Experimentations and Concessions in the Southern Caribbean …115 4. Recreating the Creole Archipelago …164 PART III 5. The American Revolution and the Resurgence of the Creole Archipelago, 1774-1785 …210 6. The French Revolution and the Demise of the Creole Archipelago …251 Epilogue …290 Appendix A: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of Dominica …301 Appendix B: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of St. Vincent …310 A Note on Sources …316 Bibliography …319 ii List of Tables 1.1: Respective Populations of France’s Windward Island Colonies, 1671 & 1700 …32 1.2: Respective Populations of Martinique, Grenada, St. Lucia, Dominica, and St. Vincent c.1730 …39 1.3: Change in Reported Population of Free People of Color in Martinique, 1732-1733 …46 1.4: Increase in Reported Populations of Dominica & St. Lucia, 1730-1745 …50 1.5: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in the Lesser Antilles, 1626-1762 …57 1.6: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in Jamaica & Saint-Domingue, 1526-1762 …58 2.1: Reported Populations of the Ceded Islands c. -

List of Projects- Stewardfish Microgrants Scheme for Caribbean Fisherfolk Organisations

List of projects- StewardFish Microgrants Scheme for Caribbean Fisherfolk Organisations On July 1, 2020 CANARI launched the call for applications for the USD20,000 StewardFish Microgrants Scheme for Caribbean Fisherfolk Organisations. The overall goal of the microgrant scheme is to provide support to Caribbean fisherfolk organisations for organisational strengthening initiatives that will enhance their capacity to participate in coastal and marine resources governance and management, including ecosystem stewardship. The call targeted the following five fisherfolk organisations participating in StewardFish: 1. Barbuda Fisherfolk Association – Antigua and Barbuda 2. Barbados National Union of Fisherfolk Organisations (BARNUFO) – Barbados 3. Guyana National Fisherfolk Organisation (GNFO)- Guyana 4. Saint Lucia Fisherfolk Cooperative Society Limited – Saint Lucia 5. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines National Fisherfolks Co-Operative Limited (SVGNFO) – Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Each of the targeted fisherfolk organisations successfully submitted proposals to the microgrant scheme and were each awarded a USD4,000 microgrant for their projects which will run from November 2020 to April 2021. Table 1: List of StewardFish fisherfolk organisational strengthening projects Fisherfolk organisation Project title Project goal Barbados National iFish: Piloting an online To promote organisational strengthening Union of Fisherfolk platform for of BARNUFO to effectively mobilise Organizations organisational resources and build the capacity of its (BARNUFO) -

No. 5 THURSDAY Second Session 28Th March, 2002 Seventh

No. 5 THURSDAY Second Session 28 th March, 2002 Seventh Parliament SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES THE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) ADVANCE COPY OFFICIAL REPORT CONTENTS Thursday 28 th March, 2002 Prayers 6 Announcements by Speaker 6 Obituaries 6 Congratulatory Remarks 9 Minutes 12 Announcement by Speaker 13 Motion 13 Statements by Ministers 13 Motion 25 The Spiritual Baptists’ (Official Recognition of Freedom to Worship Day) Bill, 2002 (First, second and third readings) 25 Reports from Select Committee 44 The Finance Bill, 2002 (First, second and third readings) 45 The Commissions of Inquiry (Amendment) Bill, 2002 (First, second and third readings) 46 Carnival Development Corporation Bill, 2002 (First reading) 71 Internationally Protected Persons Bill, 2002 (First reading) 71 Act against the taking of Hostages Bill, 2002 (First reading) 72 Adjournment 73 THE THE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE FIFTH MEETING, SECOND SESSION OF THE SEVENTH PARLIAMENT OF SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES CONSTITUTED AS SET OUT IN SCHEDULE 2 TO THE SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES ORDER, 1979. th TWELFTH SITTING 28 March 2002 HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY The Honourable House of Assembly met at 10.15 a.m. in the Assembly Chamber, Court House, Kingstown. PRAYERS MR. SPEAKER IN THE CHAIR Honourable Hendrick Alexander Present MEMBERS OF CABINET Prime Minister, Minister of Finance, Planning, Economic Development, Labour, Information, Grenadines and Legal Affairs. Dr. The Honourable Ralph Gonsalves Member for North Central Windward Attorney General Honourable Judith Jones-Morgan Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Commerce and Trade. Honourable Louis Straker Member for Central Leeward 3 Minister of National Security, the Public Service and Airport Development Honourable Vincent Beache Member for South Windward Minister of Education, Youth and Sports Honourable Michael Browne Member for West St. -

The Garifuna Legacy in New York City By: Jose Francisco Avila

The Garifuna Legacy in New York City By: Jose Francisco Avila Did you know that Garinagu may have been in the USA since the 1800s? Although there is no official record of when the first Garinagu arrived in North America, a New York City theater playbill revealed that Garifunas may have migrated during the nineteenth century. The playbill was for an 1823 play about Garifuna hero Joseph Chatoyer. Playwright William Henry Brown was believed to be a Garifuna from St. Vincent. His play, The Drama of King Shotoway, a play which is recognized as the first black drama of the American Theatre, which has as its subject the 1795 Black Caribs Insurrection in the Island of Saint Vincent, led by the Paramount Chief Joseph Chatoyer. Brown's play was staged at the African Grove Theatre, which was located at the corners of Mercer and Bleecker streets. Founded in 1821, it was the first African American theater, according to the program. 1 New York City is home to the largest Black Caribs (Garifunas) population outside of Honduras in Central America, an estimated 200,000 live in the South Bronx, Brownsville and East New York of Brooklyn, and on Manhattan's Upper West Side. In 2009, the Garifuna Community of New York City will celebrate some key milestones, among them the 186 th anniversary of the Drama of King Shotoway. In addition, it will celebrate the 63 rd anniversary of the Carib American Association, Inc., the 50 th anniversary of the Fenix Social Club, Inc and the 20 th anniversary of Mujeres Garinagu en Marcha (MUGAMA), Inc. -

Ministry of Health, Wellness & the Environment St

MINISTRY OF HEALTH, WELLNESS & THE ENVIRONMENT ST. VINCENT & THE GRENADINES NATIONAL ACTION PLAN for the PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF NON - COMMUNICABLE DISEASES 2017 – 2025 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS……………………………………………………………………… ... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... 3 ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................. 5 FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................. 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 7 DEVELOPMENT OF THE ACTION PLAN ................................................................................ 8 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 8 Rationale ............................................................................................................................... 9 Scope ................................................................................................................................... 10 Situational Analysis ............................................................................................................ 10 The Mandate ...................................................................................................................... -

Deployment of an AWAC Off the East Coast of St Vincent, 2018-2019 Judith Wolf, Giles Williams and James Ayliffe

National Oceanography Centre Research & Consultancy Report No. 69 Deployment of an AWAC off the east coast of St Vincent, 2018-2019 Judith Wolf, Giles Williams and James Ayliffe October 2019 This report is part of the NOC-led project “Climate Change Impact Assessment: Ocean Modelling and Monitoring for the Caribbean CME states”, 2018-2019; under the Commonwealth Marine Economies (CME) Programme in the Caribbean. National Oceanography Centre Joseph Proudman Building 6 Brownlow St Liverpool L3 5DA UK email: [email protected] 1 2 Table of Contents Summary .............................................................................................................................. 5 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Background, aim and objectives of the study .......................................................... 7 1.2 Study Area – Saint Vincent and the Grenadines ..................................................... 7 1.3 Oceanographic description of the study area .......................................................... 9 2 Purchase of a wave gauge for St Vincent and Grenadines .......................................... 10 3 AWAC deployment ....................................................................................................... 11 3.1 July-October 2018................................................................................................. 14 3.2 January-March 2019 ............................................................................................ -

Meeting the Managua Challenge National

Meeting The Managua Challenge In November 2000, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) challenged governments of the Americas to accelerate their destruction of stockpiled antipersonnel mines ahead of the September 2001 meeting of States Parties to the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, which will be held in Managua, Nicaragua. It also urged the remaining signatories and non- signatories to fully join the treaty by September 2001 and for all States Parties to submit their initial transparency reports as required under Article 7 of the ban treaty. An update on this Managua Challenge shows significant progress made by many countries since November 2000 to meet the Challenge: Three signatories ratified: Chile, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Uruguay. Three States Parties have completed stockpile destruction: Ecuador, Honduras, and Peru. Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, and Uruguay destroyed some stockpiled mines. Six more States Parties have submitted their initial transparency reports:Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Paraguay. Two States Parties enacted national implementation legislation in 2001:Brazil and Trinidad and Tobago. One States Party will reduce the number of antipersonnel mines retained for training and development, as permitted under the Article 3 of the treaty: Peru will reduce the number from 9,526 to 5,578. Thirty of the thirty-five countries in the Americas region are State Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty. Since November 2000, there have been three ratifications: Uruguay (7 June 2001), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (1 August 2001), and Chile (10 September 2001). Three remaining signatories that have not ratified: Guyana, Haiti, and Suriname. Cuba and the United States remain the only two countries in the region that have not joined the Mine Ban Treaty.