International Cities: Case Studies US: Cleveland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jackson Intends to Run Fof Mayor

Workshop·on college funding to be held Society to hold Western event New city planning director named SPORTS MENU TIPS A free workshop on the "9 Ways To Beat The The American Cancer Society, Cuyahoga Divi Mayor Jane Campbell recently named Robert High Cost Of College" will be held on Tuesday, January 25 sion, plans to rope in Greater Clevelanders with what should Brown as the new city planning director. The city planning Cavs Beat Boozer's Tips For from 6:30p.m. to 7:30p.m. at the Solon High School be the most extraordinary party in Ohio: the Cattle Baron's director oversees the city's long term land use and zoning Lecture Hall, 33600 Inwood Road in Solon. The workshop BaJI. The inaugural Cattle Baron's BaJI will be Saturday plans aJong with other responsibilities. The position opened Jazz On Road Trip Winter Parties will cover many topics, including how to double or even April 9, in the CLub Lounge at Cleveland Bown's Stadium. up after CampbeiJ chose former City Planning director triple your eligibility for financial aid, how to construct a Tickets and sponsorship opportunities are available now by Chis Ronayne as her new chief of staff. Brown has worked plan to pay college costs, and what colleges will give you calling (216) 241-11777. The Northern Ohio Toyota Deal for the City Planning Commission for 19 years. For the See Page 9 See Page 10 the best financial aid packages. Reservations are required. ers have jumped in the driver's seat as the event's present last 17 years, Brown was the assistant city planning direc For more information call (888) 845-4282. -

Visito Or Gu Uide

VISITOR GUIDE Prospective students and their families are welcome to visit the Cleveland Institute of Music throughout the year. The Admission Office is open Monday through Friday with guided tours offered daily by appointment. Please call (216) 795‐3107 to schedule an appointment. Travel Instructions The Cleveland Institute of Music is approximately five miles directly east of downtown Cleveland, off Euclid Avenue, at the corner of East Boulevard and Hazel Drive. Cleveland Institute of Music 11021 East Boulevard Cleveland, OH 44106 Switchboard: 216.791.5000 | Admissions: 216.795.3107 If traveling from the east or west on Interstate 90, exit the expressway at Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive. Follow Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive south to East 105th Street. Cross East 105th and proceed counterclockwise around the traffic circle, exiting on East Boulevard. CIM will be the third building on the left. Metered visitor parking is available on Hazel Drive. If traveling from the east on Interstate 80 or the Pennsylvania Turnpike, follow the signs on the Ohio Turnpike to Exit 187. Leave the Turnpike at Exit 187 and follow Interstate 480 West, which leads to Interstate 271 North. Get off Interstate 271 at Exit 36 (Highland Heights and Mayfield) and take Wilson Mills Road, westbound, for approximately 7.5 miles (note that Wilson Mills changes to Monticello en route). When you reach the end of Monticello at Mayfield Road, turn right onto Mayfield Road for approximately 1.5 miles. Drive two traffic lights beyond the overpass at the bottom of Mayfield Hill and into University Circle. At the intersection of Euclid Avenue, proceed straight through the traffic light and onto Ford Road, just three short blocks from the junction of East Boulevard. -

City Record Official Publication of the Council of the City of Cleveland

The City Record Official Publication of the Council of the City of Cleveland January the Thirtieth, Two Thousand and Nineteen The City Record is available online at Frank G. Jackson www.clevelandcitycouncil.org Mayor Kevin J. Kelley President of Council Containing PAGE Patricia J. Britt City Council 3 City Clerk, Clerk of Council The Calendar 14 Board of Control 14 Ward Name Civil Service 16 1 Joseph T. Jones Board of Zoning Appeals 20 2 Kevin L. Bishop Board of Building Standards 3 Kerry McCormack and Building Appeals 21 4 Kenneth L. Johnson, Sr. Public Notice 21 5 Phyllis E. Cleveland Public Hearings 21 6 Blaine A. Griffin City of Cleveland Bids 21 7 Basheer S. Jones Adopted Resolutions and Ordinances 22 8 Michael D. Polensek Committee Meetings 22 9 Kevin Conwell Index 22 10 Anthony T. Hairston 11 Dona Brady 12 Anthony Brancatelli 13 Kevin J. Kelley 14 Jasmin Santana 15 Matt Zone 16 Brian Kazy 17 Martin J. Keane Printed on Recycled Paper DIRECTORY OF CITY OFFICIALS CITY COUNCIL – LEGISLATIVE DEPT. OF PUBLIC SAFETY – Michael C. McGrath, Director, Room 230 President of Council – Kevin J. Kelley DIVISIONS: Animal Control Services – John Baird, Interim Chief Animal Control Officer, 2690 West 7th Ward Name Residence Street 1 Joseph T. Jones...................................................4691 East 177th Street 44128 Correction – David Carroll, Interim Commissioner, Cleveland House of Corrections, 4041 Northfield 2 Kevin L. Bishop...............................................11729 Miles Avenue, #5 44105 Rd. 3 Kerry McCormack................................................1769 West 31st Place 44113 Emergency Medical Service – Nicole Carlton, Acting Commissioner, 1708 South Pointe Drive 4 Kenneth L. Johnson, Sr. -

THE COUNCIL for ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITIES in Greater

THE COUNCIL FOR ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITIES in Greater Cleveland HISTORY SNAPSHOT 1964 Unconditional War on Poverty is declared by President Johnson in his State of the Union address. Ralph M. Besse, President of the Cleveland Illuminating Company, elected the first President of the Board of Trustees. CEOGC is incorporated as a private, non-profit corporation to apply for federal grants under the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964; and is authorized as prime contractor and coordinating agency in Cuyahoga County. 1965 Ralph S. Locher, former Mayor of Cleveland, is elected President of CEOGC Board of Trustees, Ralph W. Findley is appointed Executive Director of the Council for Economic Opportunities in Greater Cleveland. Project Head Start, an eight week summer program, is announced. CEOGC Board of Trustees receives notice that the Head Start Program is funded for $815,000. Carver Park and Dare become the first Head Start sites to open in Cleveland. CEOGC Board approves $120,000 grant to the Council of Churches for a pre-school nursery program on Cleveland's West Side. CEOGC announces that funding is available for the Reading Improvement Program ($487,606) and work study ($159,855); both programs to be sub-contracted for operation to the Cleveland Board of Education. CEOGC Board approves general and open election procedures to seat five new members on the board, representing low-income persons in five social planning target areas. 1966 CEOGC receives a $1.1 million federal letter of credit for Adult Education, Reading Improvement and Work Study in Cleveland. CEOGC approves $18,600 Head Start Grant for East Cleveland Schools and a $502,000 Head Start Grant for Cleveland Public Schools. -

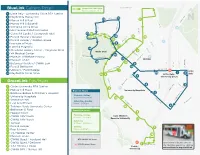

Circlelink Shuttle Map.Pdf

BlueLink Culture/Retail GreenLink AM Spur 6:30-10:00am, M-F 1 Little Italy - University Circle RTA Station 2 Mayfield & Murray Hill 11 3 Murray Hill & Paul 12 11 4 Murray Hill & Edgehill 5 Cornell & Circle Drive 6 UH Cleveland Medical Center 7 Cornell & Euclid / Courtyard Hotel 13 13B 8 Ford & Hessler / Uptown 10 12 10 13A 9 Ford & Juniper / Glidden House 10 Institute of Music 9 13 11 Hazel & Magnolia 14 12 Cleveland History Center / Magnolia West Wade Oval 9 13 VA Medical Center MT SINAI DR 16 14 Museum of Natural History 17 Uptown 15 Museum of Art T S 15 8 16 5 Botanical Garden / CWRU Law 0 8 1 17 Ford & Bellflower E 18 18 Uptown / Ford Garage 7 Little 19 1 2 19 Mayfield & Circle Drive 14 6 Italy 7 GreenLink Eds/Meds 6 3 1 Cedar-University RTA Station 5 2 Murray Hill Road BlueLink Hours University Hospitals 3 Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital 5 Monday—Friday 4 University Hospitals 10:00am—6:00pm 15 4 5 Severance Hall Saturday—Sunday 6 East & Bellflower Noon—6:00pm 7 Tinkham Veale University Center 16 4 8 Bellflower & Ford GreenLink Hours 9 Hessler Court 3 Monday—Friday 10 CWRU NRV South Case Western 6:30am—6:30pm Reserve University 11 CWRU NRV North 17 Saturday 12 Juniper 6:30am—6:00pm T S 13 Ford & Juniper Sunday D 2 N 13A 2 Noon—6:00pm East & Hazel 0 1 13B VA Medical Center E 18 14 Museum of Art 15 CWRU Quad / Adelbert Hall 16 CWRU Quad / DeGrace 1 GetGet real-timereal-time arrshuttleival in infofo vi avia the NextBus app or by visiting 17 1-2-1 Fitness / Veale the NextBus app or by visiting universitycircle.org/circlelinkuniversitycircle.org/circlelink 18 CWRU SRV / Murray Hill GreenLink Schedule Service runs on a continuous loop between CWRU CircleLink is provided courtesy of these North and South campuses, with arrivals sponsoring institutions: approximately every 30 minutes during operating hours and 20-minute peak service (Mon-Fri) Case Western Reserve University between 6:30am - 10:00am and 4:00pm - 6:30pm. -

Cleveland's Greater University Circle Initiative

Cleveland’s Greater University Circle Initiative An Anchor-Based Strategy for Change Walter Wright Kathryn W. Hexter Nick Downer Cleveland’s Greater University Circle Initiative An Anchor-Based Strategy for Change Walter Wright, Kathryn W. Hexter, and Nick Downer Cities are increasingly turning to their “anchor” institutions as drivers of economic development, harnessing the power of these major economic players to benefit the neighborhoods where they are rooted. This is especially true for cities that are struggling with widespread poverty and disinvestment. Ur- ban anchors—typically hospitals and universities—have some- times isolated themselves from the poor and struggling neigh- borhoods that surround them. But this is changing. Since the late 1990s, as population, jobs, and investment have migrated outward, these “rooted in place” institutions are becoming a key to the long, hard work of revitalization. In Cleveland, the Greater University Circle Initiative is a unique, multi-stake- holder initiative with a ten-year track record. What is the “se- cret sauce” that keeps this effort together? Walter W. Wright is the Program Manager for Economic Inclusion at Cleveland State. Kathryn W. Hexter is the Director of the Center for Community Planning and Development of Cleveland State University’s Levin College of Urban Affairs. Nick Downer is a Graduate Assistant at the Center for Community Planning and Development. 1 Cleveland has won national attention for the role major non- profits are playing in taking on the poverty and disinvest- ment plaguing some of the poorest neighborhoods in the city. Where once vital university and medical facilities built barri- ers separating themselves from their neighbors, now they are engaging with them, generating job opportunities, avenues to affordable housing, and training in a coordinated way. -

Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Cleveland Memory Books Summer 7-2013 Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times Richard Klein Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevmembks Part of the United States History Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Klein, Richard, "Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times" (2013). Cleveland Memory. 18. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevmembks/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland Memory by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times Richard Klein, Ph.D Cleveland Mayor Ralph J. Perk: Strong Leadership During Troubled Times Richard Klein, Ph.D An online accessible format of this book can be found at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevmembks/18/ The digital version is brought to you for free and open access at EngagedScholarship@CSU. 2013 MSL Academic Endeavors Imprint of Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University Published by MSL Academic Endeavors Cleveland State University Michael Schwartz Library 2121 Euclid Avenue Rhodes Tower, Room 501 Cleveland, Ohio 44115 http://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/ ISBN: 978-1-936323-02-9 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License CLEVELAND MAYOR RALPH J. PERK STRONG LEADERSHIP DURING TROUBLED TIMES TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 3 Acknowledgments 4 Introduction 7 Chapter 1: Pressing New Urban Challenges 8 Chapter 2: The Life and Times of Ralph J. -

Sustainable Cleveland Summit Presented by the Cleveland Foundation

9th Annual Sustainable Cleveland Summit Presented by The Cleveland Foundation Participant Guide September 27th and 28th, 2017 Public Auditorium Cleveland, OH Thank you to our Presenting Sponsor Established in 1914, the Cleveland Foundation is the world's first community foundation and one of the largest today, with assets of $2.13 billion and 2016 grants of $93.6 million. Through the generosity of donors, the foundation improves the lives of residents of Cuyahoga, Lake and Geauga counties by building community endowment, addressing needs through grantmaking and providing leadership on vital issues. The foundation tackles the community’s priority areas – education and youth development, neighborhoods, health and human services, arts and culture, economic development and purposeful aging – and responds to the community’s needs. For more information on the Cleveland Foundation, visit www.ClevelandFoundation.org. 2 Welcome to the 9th Annual Sustainability Summit! Thank you for joining me at the 9th Annual Sustainable Cleveland Summit, presented by the Cleveland Foundation. Sustainable Cleveland 2019 is a ten-year initiative that engages the entire community to design and develop a sustainable economy for Cleveland. We have the resources, the people, and the ideas to make our regional economy strong, resilient, and equitable. Sustainable Cleveland 2019 has gained support and grown in scope, breadth, and numbers since it launched in 2009. We have engaged thousands of people. The result has been a wide variety of initiatives addressing the full spectrum of sustainability. As we prepare for the next year in our initiative, we are building off of this past momentum, while continuing to promote boldness, creativity, and action. -

Cleveland in a Nutshell

Cleveland in a Nutshell Cleveland Clinic House Staff Spouse Association The House Staff Spouse Association (HSSA) would like to welcome all new Cleveland Clinic residents, fellows and their families to Cleveland. We can help make this move and new phase of your life a little easier. Cleveland in a Nutshell is a resource we hope you will find useful! The information in this booklet is a compilation of information gathered by past and current Cleveland Clinic spouses. It will help you during your relocation to Cleveland and once you’re settled in your new home. After you arrive in Cleveland, the HSSA is a great way to meet new friends and take part in fun events. Our volunteer group is subsidized by the Cleveland Clinic and organizes affordable social functions for residents, fellows, and their families. From discount sporting event tickets to play dates, we are a social and support network. Membership is free and there are no commitments, except to have fun! Look for our monthly meetings and events in our monthly HSSA newsletter – The Stethoscoop-- which will be mailed to your home in Cleveland and addressed to the resident/fellow. In addition to the newsletter, we also have an online community through Yahoo groups! There are over 100 members and we encourage you to join and become an active member in our community. Please email [email protected] for more details. If you have any questions before you arrive, please don’t hesitate to contact one of our officers: President - Erin Zelin (216)371-9303 [email protected] Vice President - Annie Allen (216)320-1780 [email protected] Stethoscoop Editor - Jennifer Lott (216)291-5941 [email protected] Membership Secretary - MiYoung Wang (216)-291-0921 [email protected] PLEASE NOTE: The information presented here is a compilation of information from past and current CCF spouses. -

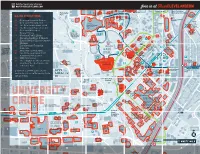

University Circle

Join in at ThisisCLEVELAND.COM Junior University Magnolia League of Circle Inc. Montes sori The Music Nobby’s Ballpark East Cleveland Clubhouse Settlement Rockefeller Mount Zion Cleveland Hawken School High School Township Cemetery at University Circle M NE AVE Congregational AGN Circle Health BLAI Park Sally and Bob OLIA D E Church RI Services M Gries Center at VE A MAJOR ATTRACTIONS MA Cleveland S A GNOLIA DRIVE Cleveland R University Circle Gestalt T East T E I Friends E 1 Public Library, A Institute 1 N A Cleveland Township 8 S L R Meeting S I T Hough Branch U S T of Cleveland T T O H Cemetery 1 C2 Cleveland Botanical Garden H N 1 E 0 MORE AVE – S KEN K 1 Euclid ENM R D 8 OR T E A 5 VENUE K I T L R Cleveland T C1 IN L H Gate Cleveland History Center E A H G DiSanto E R Louis Stokes S History Center S T J D T Field The Sculpture Center R T Cleveland Veterans B E2 The Cleveland Institute of Art R D and Artists Archives MERIDIAN AVE I R K Affairs Medical E 1 H I E E of the Western Reserve V A Center T E C2 The Cleveland Museum of Art R E R IV I S R D C1 Cleveland Museum of O L University N ZE E E Rockefeller – A 1 D H Circle Police 2 D H A Cleveland AR A D 3 I K Natural History S N O Lagoon R D R ES L Judge Jean A Department S R R T V Institute A D D T AVENUE L E O LBO TA L S D 9 A Murrell Capers U of Music R T 3 C3 ClevelandO Public Library, R O R E Centers for E O R D B E A Tennis Courts V R D S T I IP Dialysis Care Y B Linsalata T S R D L S I N MartinO Luther King, Jr. -

Timothy J. Cosgrove

2020 Walks of Life Honoree Timothy J. Cosgrove During his 40-year career, Tim Cosgrove has worked tirelessly on behalf of the citizens of Cleveland and the state of Ohio. As a result of his efforts, he has been recognized as an Ohio Super Lawyer and is one of Ohio’s most highly recognized lobbyists. At age 18, Tim was working as a waiter at a downtown restaurant when one day George Voinovich, then the mayor of Cleveland, sat down at the table he was serving. The teenager apparently impressed the mayor because a few months later Tim was offered a job in the city’s Community Development Department. Originally from Cleveland’s Collinwood neighborhood, Tim earned a bachelor’s degree in political science from Cleveland State University and a law degree from the university’s law school, all while working for the city and as a waiter in downtown restaurants. In 1987 when Tim was only 26, he was named as an assistant to the mayor of Cleveland, helping oversee the Mayor’s State and Federal Government Policy Agendas. Five years later, when Voinovich became Ohio governor, Tim was appointed Director of Legislation and Policy and was responsible for driving the Governor’s agenda through the Ohio General Assembly. While working for the Governor, he also helped to oversee the development of the Gateway project and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, among other civic undertakings. Tim decided to leave government work in 1993 and joined the Cleveland-based law firm of Squire Patton Boggs. He credits his work in City Hall for giving him the practical experience in government and politics that has led to his present success. -

Cleveland Neighborhoods

The Beachland Ballroom COLLINWOOD Bratenahl Cleveland Lakefront 1 Nature Reserve East Gordon Cleveland 90 Park Stokes– 1 10 Windermere East 55th Street GLENVILLE Marina Lke ie AY W E T 3 R O Rockefeller S H S S T. CL A IR – Park 5 AL 0 I 1 R SUPERIOR O E EM M 3 D E N AV Burke Lakefront A E L IR OR AV E A UPERI Cleveland Airport V CL S E T Museum CL S Great Lakes 1 T University of Art S 3 Lake View Science Center 9 HOUGH 7 Circle Cemetery E Little Italy– MIDTOWN MOCA University Circle Cleveland Downtown Heights Playhouse ER AVE University Little FirstEnergy HEST HealthLine Square C AVE Hospitals Stadium JACK EUCLID Italy Cleveland Cleveland Severance Cleveland State CARNEGIE AVE Hall Case Western Casino University Clinic Reserve Whiskey Quicken Loans T S University Island Arena 5 5 FAIRFAX CENTRAL T E Tower S 11 0 QUINCY AVE City– 3 Edgewater Progressive Public E D R CLIFTON BLVD Park Field L Square Red Line L Detroit 90 I LARCHMERE BLVD Cleveland State Line WOODLAND AVE H Shaker D 26 O Square Shoreway O 26 W. 25th St.– W DETROIT AVE edgewater Cleveland West Side Public Theatre Market Ohio City 11 VE Green Line T A Ohio Lakewood DETRO I W. 65th St.– Blue Line Lorain City 490 Shaker KINSMAN BUCKEYE– 81 Tremont 22 Red Line 51 T Square S WOODHILL 6 20 A Christmas 19 K 1 IN 1 cudell SMA Story House N R E T D S CLARK– T 10 5 S 6 FULTON Rocky 5 B 2 W R 90 O River W A NION AVE Mount D U Rocky River 22 81 77 W AY PLEASANT MetroHealth CUYAHOGA A Reservation D 81 V R Hospital E E D STOCKYARDS VALLEY West AV E N N T IN I O A S T S Park R O BROADWAY–