Interstate 50Th Anniversary: the Story of Oregon's Interstates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide A Complete Compendium Of RV Dump Stations Across The USA Publiished By: Covenant Publishing LLC 1201 N Orange St. Suite 7003 Wilmington, DE 19801 Copyrighted Material Copyright 2010 Covenant Publishing. All rights reserved worldwide. Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide Page 2 Contents New Mexico ............................................................... 87 New York .................................................................... 89 Introduction ................................................................. 3 North Carolina ........................................................... 91 Alabama ........................................................................ 5 North Dakota ............................................................. 93 Alaska ............................................................................ 8 Ohio ............................................................................ 95 Arizona ......................................................................... 9 Oklahoma ................................................................... 98 Arkansas ..................................................................... 13 Oregon ...................................................................... 100 California .................................................................... 15 Pennsylvania ............................................................ 104 Colorado ..................................................................... 23 Rhode Island ........................................................... -

The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report

The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report January 2003 Ove Arup & Partners International Ltd Admiral House, Rose Wharf, 78 East Street, Leeds LS9 8EE Tel +44 (0)113 242 8498 Fax +44 (0)113 242 8573 REP/FI Job number 68772 The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION 9 1.1 Scope of the Report 9 1.2 Study Background and Objectives 9 1.3 Transport Trends 10 1.4 Planning Context 10 1.5 The Integrated Transport Initiative 11 1.6 Study Approach 13 1.7 Light Rapid Transit Systems 13 2. PHASE 1 APPRAISAL 18 2.1 Introduction 18 2.2 Corridor Review 18 2.3 Development Proposals 21 2.4 The City of Edinburgh Conceptual Network 22 2.5 Priorities for Testing 23 2.6 North Edinburgh Loop 24 2.7 South Suburban Line 26 2.8 Appraisal of Long List of Corridor Schemes 29 2.9 Phase 1 Findings 47 3. APPROACH TO PHASE 2 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Technical Issues and Costs 50 3.3 Rolling Stock 54 3.4 Tram Services, Run Times and Operating Costs 55 3.5 Environmental Impact 55 3.6 Demand Forecasting 56 3.7 Appraisal 61 4. NORTH EDINBURGH LOOP 63 4.1 Alignment and Engineering Issues 63 4.2 Demand and Revenue 65 4.3 Environmental Issues 66 4.4 Integration 67 4.5 Tram Operations and Car Requirements 67 4.6 Costs 68 4.7 Appraisal 69 5. -

Umatilla Ped-Bike Plan

U m a t i l l a Pedestrian & Bicycle MASTER PLAN June 3, 2003 David Evans and Associates, Inc. Umatilla Pedestrian & Bicycle Master Plan 1 (UMAT0001) This project is partially funded by the Transportation and Growth Management Program (TGM), a joint program of the Oregon Department of Transportation and the Oregon Department of Land Development and Conservation. This TGM grant is fi nanced, in part, by federal Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21), local government, and the State of Oregon Funds. Neither the City of Umatilla nor ODOT guarantee funding to complete any project described in this document. Historic Umatilla River bridge David Evans and Associates, Inc. Umatilla Pedestrian & Bicycle Master Plan 2 (UMAT0001) Contents Chapter 1 — Scope . 5 Chapter 2 — Background Research . 6 2.1 Sources . 6 2.2 Area Description . 6 2.3 Jurisdictions . 6 2.4 Nonmotorized Traffi c Generators . 7 2.5 Implementation Plan . 9 Chapter 3 — Inventory . 10 3.1 Street System . 10 3.2 Pedestrian Facilities . 11 3.3 Bicycle Facilities . 12 Chapter 4 — Systemwide Factors . 14 4.1 Natural and Manmade Barriers . 14 4.2 Development Pattern . 14 4.3 Street Standards and Development Codes . 15 4.4 Funding . 17 Chapter 5 — Neighborhood Analysis . 23 5.1 Project Evaluation Criteria . 23 5.2 South Hill Projects . 26 5.3 Downtown Umatilla Projects . 36 5.4 Central Area Projects . 41 5.5 McNary Projects . 45 Chapter 6 — Capital Improvement Program . 49 Appendix A — Glossary . A-1 Appendix B — Pedestrian & Bicycle System Maps . B-1 Appendix C — Transportation SDC Example . C-1 Appendix D — General Plan and Code Amendments D-1 Appendix E — Inter-Jurisdictional Agreements . -

Northwest Area Fire Weather Annual Operating Plan

Williams Flats Fire: August 7, 2019 Photo: Inciweb 2021 Northwest Area Fire Weather Annual Operating Plan 1 This page intentionally left blank 2 3 This page intentionally left blank 4 Table of Contents Agency Signatures/Effective Dates of the AOP ......................................................................................3 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................6 NWS Services and Responsibilities.........................................................................................................8 Wildland Fire Agency Services and Responsibilities ........................................................................... 14 Joint Responsibilities ...........................................................................................................................15 NWCC Predictive Services ...................................................................................................................17 Boise .................................................................................................................................................. 25 Medford...............................................................................................................................................30 Pendleton ........................................................................................................................................... 41 Portland...............................................................................................................................................53 -

Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project

Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project I-5 North Coast Corridor Project Final EIR/EIS page L-1 Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project I-5 North Coast Corridor Project Final EIR/EIS page L-2 Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project September 2013 Prepared by: Caltrans District 11 | T.Y. Lin International | Safdie Rabines Architects | Estrada Land Planning Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project Prepared by: Caltrans District 11 4050 Taylor Street San Diego, CA 92110 T.Y. Lin International 404 Camino del Rio South, Suite 700 San Diego, CA 92108 | 619.692.1920 Safdie Rabines Architects 925 Ft. Stockton Drive San Diego, CA 92123 | 619.297.6153 Estrada Land Planning 755 Broadway Circle, Suite 300 San Diego, CA 92101 | 619.236.0143 Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Table of Contents Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project Table of Contents I. Project Background D. Design Themes....................17 vi. Typical Freeway Undercrossing. 36 vii. Typical Bridge Details. 37 A. Introduction....................1 i. Corridor Theme Elements. 17 ii. Corridor Theme Priorities. 19 - Southern Bluff Theme....................38 B. Purpose.......................1 - Coastal Mesa Theme.....................39 iii. Corridor Theme Units. 20 C. Components & Products. 1 - Northern Urban Theme. 40 - Southern Bluff Theme....................21 D. The Proposed Project. 2 - Coastal Mesa Theme.....................22 B. Walls.............................41 E. Previous Relevant Documents. 3 - Northern Urban Theme. 23 i. Theme Unit Specific Wall Concepts. -

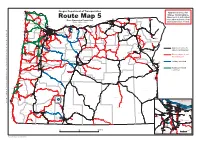

Route Map 5 Ä H339 Æ

ASTORIA Oregon Department of Transportation Warrenton H104 Svensen Approved routes for Mayger 30 Westport ¤£ Clatskanie Æ 101 Olney Ä Rainier ¤£ H105 Triples Combinations. Æ Gearhart C L A T S O PÄ 47 Prescott SEASIDE Goble H332 202 Mist 73300 Movement is authorized 395 Umapine Necanicum Cold ¤£2 Jewell ¤£ Springs Jct. C O L U M B I A Æ Ä MP 9.76 Umatilla Jct. Milton-Freewater Flora Ä Æ Æ Cannon Beach Route Map 5 Ä H339 Æ H103 Pittsburg Irrigon Ä only under authority of an Columbia City Æ Over-Dimension Permit Unit Ä Elsie 47 730 Holdman 53 ST. HELENS ¤£ Helix 11 Vernonia Boardman 0 207 26 7 30 82 Athena Æ ¤£ Ä Over-Dimension Permit. ¤£ Revised March 2020 HERMISTON 3 ¨¦§ H Heppner Jct. Æ Ä H334 Weston Scappoose Stanfield 3 Nehalem 3 Adams 204 Manzanita HOOD Permission not granted to 5 RIVER cross RR crossing at MP 102.40 30 37 Æ 84 30 Echo Ä Wheeler Buxton £ in Hood River 84 ¤£ Arlington H W A L L O W A ¤ 3 Cascade ¨¦§ Biggs § MP 13.22 ¨¦ 26 Locks Jct. Rufus 3 Æ Rockaway Celilo Blalock Ä H320 1 Æ T I L L A M O O K ¤£ Mosier Ä 82 Beach Banks North H281 PENDLETON Plains PORTLAND Æ Ä Minam Imnaha Odell Wallowa Æ Ä 74 Garibaldi Wasco 207 W A S H I N G T O N The Elgin . Bay City Troutdale Multnomah Æ CorneliusÄ Fairview Dalles t Forest HILLSBORO H O O D H282 206 i 6 Grove Falls G I L L I A M Wood 84 Oceanside Beaverton R I V E R U M A T I L L A Summerville m H131 Village Ione r 8 ¨¦§ Lostine Æ Parkdale 197 Ä Gresham Moro 0 e Tillamook M U L T N O M A H MP 83.00 ¤£ 30 Imbler 5 Netarts ENTERPRISE Æ Ä Pilot 3 Æ Ä £ Æ Ä ¤ p Æ Ä Rock H Gaston Tigard -

Last Link of I-90 Ends 30-Year Saga by Peggy Reynolds, Seattle Times, 9 Sept 1993

Last Link Of I-90 Ends 30-Year Saga By Peggy Reynolds, Seattle Times, 9 Sept 1993 Erica Clibborn's red convertible will be one of the first cars Sunday across the new Lacey V. Murrow Floating Bridge, last link in a project that started before Erica was born. The University of Washington junior, who will be going home to Mercer Island for Sunday dinner, was born in 1973, the year a federal court sent the Seattle-area stretch of Interstate 90 back to square one. By then, I-90 already reached most of the 3,063 miles from Boston to south Bellevue, and the final major segment had been in the works for 10 years. It would be another 20 years before that last 7 miles would be finished. That completion will be marked this weekend with an array of public events, and Clibborn and other drivers should be able to go across the eastbound span by 5 p.m. Sunday. That opening means that I-90 survived the anti-government sentiment of the late 1960s, the mass-transit worship of the '70s and the budget cutbacks of the '80s - even while other urban interstate projects were biting the dust in New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Washington, San Francisco and Portland. Nevertheless, whether or not I-90 was really needed was subject to debate at all levels. It attracted a formidable enemies list, and was rescued regularly by a cast of hundreds. Without any one of its friends in local governments, on the state Transportation Commission, in the Legislature and in Congress, I-90 could have ended in south Bellevue instead of making it to its junction with Interstate 5 in Seattle. -

I-90 Tolling Update

I-90 Tolling Update John White Director of Tolled Corridors Development Paula Hammond Steve Reinmuth Secretary of Transportation Chief of Staff Seattle City Council January 28, 2012 I-90 is part of the Cross-Lake Washington Corridor • Represents two major east-west “Cross- Lake” travel corridors: I-90 and SR 520. • WSDOT is tolling SR 520 as part of a multi- faceted financing strategy to help generate enough revenue to fund replacement of the structurally-vulnerable bridge. • A new 520 bridge will give Cross-Lake WA travelers a safer, more reliable trip. 2 Funding for the SR 520 Program Construction Unfunded Program cost estimate (Oct. 2012): $4.13 billion What’s funded: $2.72 billion (includes sales tax deferral) • Pontoon construction in Grays Harbor. • The floating bridge and landings. • Eastside transit and HOV improvements. • The north half of the west approach bridge. Updated November 2012 Costs and Funding for Replacing SR 520 Bridge SR 520 program cost estimate $4.128 B Funding received to date $2.724 B State and local funding (Nickel and TPA) $0.55 B Federal funding $0.12 B SR 520 Account (tolling and future federal funds) $1.91 B Toll proceeds • TIFIA $300M • Triple pledge bonds $550M • First tier toll $159M • PAYGO $74M Federal proceeds • GARVEE $825M Deferred sales tax $0.14 B Unfunded need $1.404 B Program cost estimate based on 2012 CEVP - updated 10/25/12 4 Early Indicators of 520 Toll Success • Meeting or beating traffic forecasts. • Meeting revenue forecasts. • Most people are paying with Good To Go! accounts. – More than 384,000 active Good To Go! accounts. -

I-15 Corridor System Master Plan Update 2017

CALIFORNIA NEVADA ARIZONA UTAH I-15 CORRIDOR SYSTEM MASTER PLAN UPDATE 2017 MARCH 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The I-15 Corridor System Master Plan (Master Plan) is a commerce, port authorities, departments of aviation, freight product of the hard work and commitment of each of the and passenger rail authorities, freight transportation services, I-15 Mobility Alliance (Alliance) partner organizations and providers of public transportation services, environmental their dedicated staff. and natural resource agencies, and others. Individuals within the four states and beyond are investing Their efforts are a testament of outstanding partnership and their time and resources to keep this economic artery a true spirit of collaboration, without which this Master Plan of the West flowing. The Alliance partners come from could not have succeeded. state and local transportation agencies, local and interstate I-15 MOBILITY ALLIANCE PARTNERS American Magline Group City of Orem Authority Amtrak City of Provo Millard County Arizona Commerce Authority City of Rancho Cucamonga Mohave County Arizona Department of Transportation City of South Salt Lake Mountainland Association of Arizona Game and Fish Department City of St. George Governments Bear River Association of Governments Clark County Department of Aviation National Park Service - Lake Mead National Recreation Area BNSF Railway Clark County Public Works Nellis Air Force Base Box Elder County Community Planners Advisory Nevada Army National Guard Brookings Mountain West Committee on Transportation County -

Guide Signs for Freeways and Expressways Are Primarily Identified by the Name of the Sign Rather Than by an Assigned Sign Designation

2011 Edition Page 235 CHAPTER 2E. GUIDE SIGNS—FREEWAYS AND EXPRESSWAYS Section 2E.01 Scope of Freeway and Expressway Guide Sign Standards Support: 01 The provisions of this Chapter provide a uniform and effective system of signing for high-volume, high- speed motor vehicle traffic on freeways and expressways. The requirements and specifications for expressway signing exceed those for conventional roads (see Chapter 2D), but are less than those for freeway signing. Since there are many geometric design variables to be found in existing roads, a signing concept commensurate with prevailing conditions is the primary consideration. Section 1A.13 includes definitions of freeway and expressway. 02 Guide signs for freeways and expressways are primarily identified by the name of the sign rather than by an assigned sign designation. Guidelines for the design of guide signs for freeways and expressways are provided in the “Standard Highway Signs and Markings” book (see Section 1A.11). Standard: 03 The provisions of this Chapter shall apply to any highway that meets the definition of freeway or expressway facilities. Section 2E.02 Freeway and Expressway Signing Principles Support: 01 The development of a signing system for freeways and expressways is approached on the premise that the signing is primarily for the benefit and direction of road users who are not familiar with the route or area. The signing furnishes road users with clear instructions for orderly progress to their destinations. Sign installations are an integral part of the facility and, as such, are best planned concurrently with the development of highway location and geometric design. -

I-90: Twin Falls (North Bend Vicinity) to I-82 Jct (Ellensburg) Corridor

Corridor Sketch Summary Printed at: 3:54 PM 3/29/2018 WSDOT's Corridor Sketch Initiative is a collaborative planning process with agency partners to identify performance gaps and select high-level strategies to address them on the 304 corridors statewide. This Corridor Sketch Summary acts as an executive summary for one corridor. Please review the User Guide for Corridor Sketch Summaries prior to using information on this corridor: I-90: Twin Falls (North Bend Vicinity) to I-82 Jct (Ellensburg) This 74-mile long northwest-southeast corridor is located in King and Kittitas counties and runs between Twin Falls, just east of North Bend, and the Interstate 82 junction in the city of Ellensburg. The corridor includes a five-mile segment of US Route 97 on the eastern end of the corridor that runs concurrently with I-90. In the upper elevations of western Kittitas County, I-90 passes near Keechelus, Kachess, and Cle Elum lakes, three large reservoirs that provide irrigation water to the Kittitas and Yakima valleys. I-90 follows the Yakima River valley between the Keechelus Lake in the Snoqualmie Pass area and the city of Ellensburg. The corridor is primarily rural with some urban areas in the cities of Cle Elum and Ellensburg. The corridor travels over Snoqualmie Pass through the Cascade Mountains. On the western end of the corridor, the route is on a steep grade through heavily wooded national forest lands before reaching Snoqualmie Pass and Kittitas County. On the eastern section of the corridor, the route descends into grasslands and irrigated fields in the lower Kittitas Valley. -

Idaho Transpo Rtation De Partm

IDAHO TRANSPORTATION DEPARTMENT TRANSPORTATION IDAHO RP 226 Assessing Feasibility of Mitigating Barn Owl-Vehicle Collisions in Southern RESEARCH REPORT RESEARCH Idaho By Jim Belthoff, Erin Arnold, Tempe Regan Boise State University Tiffany Allen, Angela Kociolek Western Transportation Institute Prepared for Idaho Transportation Department Research Program, Contracting Services Division of Engineering Services http://itd.idaho.gov/highways/research/ November 2015 Standard Disclaimer This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Idaho Transportation Department and the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The State of Idaho and the United States Government assume no liability of its contents or use thereof. The contents of this report reflect the view of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Idaho Transportation Department or the United States Department of Transportation. The State of Idaho and the United States Government do not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear herein only because they are considered essential to the object of this document. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA-ID-15-226 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Assessing feasibility of mitigating barn owl-vehicle collisions in southern Idaho December 2015 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Jim Belthoff, Erin Arnold, Tempe Regan, Tiffany Allen, and Angela Kociolek 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No.