The Interstate Highway System Turns 60

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Point of Access Study

Prepared for: I-95/Scudder Falls Bridge Improvement Project Technical Memorandum No. 28 FINAL POINT OF ACCESS STUDY Contract C-393A, Capital Project No. CP0301A Prepared by: Philadelphia, PA In association with: HNTB Corporation STV Inc. Gannett Fleming, Inc. A.D. Marble & Company Kise Straw & Kolodner, Inc. Riverfront Associates, Inc. November, 2012 1 2 Technical Memorandum No. 28 – Final Point of Access Study Contract C-393A, Capital Project No. CP0301A I-95/Scudder Falls Bridge Improvement Project TABLE OF CONTENTS A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, INTRODUCTION AMD REQUIREMENTS ... 1 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................ 1 Purpose of Access......................................................................... 1 Summary of Findings .................................................................... 2 II. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 7 Project Description .............................................................. 7 Study Area Description ........................................................ 7 Project Area Description .................................................... 10 Project Purpose and Need .................................................. 11 III. REQUIREMENTS FOR APPROVAL OF ACCESS ..................................... 12 B. ENGINEERING STUDY ............................................................. 17 I. CURRENT CONDITIONS ........................................................... 17 Roadway Network -

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide A Complete Compendium Of RV Dump Stations Across The USA Publiished By: Covenant Publishing LLC 1201 N Orange St. Suite 7003 Wilmington, DE 19801 Copyrighted Material Copyright 2010 Covenant Publishing. All rights reserved worldwide. Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide Page 2 Contents New Mexico ............................................................... 87 New York .................................................................... 89 Introduction ................................................................. 3 North Carolina ........................................................... 91 Alabama ........................................................................ 5 North Dakota ............................................................. 93 Alaska ............................................................................ 8 Ohio ............................................................................ 95 Arizona ......................................................................... 9 Oklahoma ................................................................... 98 Arkansas ..................................................................... 13 Oregon ...................................................................... 100 California .................................................................... 15 Pennsylvania ............................................................ 104 Colorado ..................................................................... 23 Rhode Island ........................................................... -

Functional Classification Update Report for the Pocatello/Chubbuck Urbanized Area

Functional Classification Update Report For the Pocatello/Chubbuck Urbanized Area Functional Classification Update Report Introduction The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1973 required the use of functional highway classification to update and modify the Federal-aid highway systems by July 1, 1976. This legislative requirement is still effective today. Functional classification is the process by which streets and highways are grouped into classes, or systems, according to the character of service they are intended to provide. The functional classification system recognizes that streets cannot be treated as independent, but rather they are intertwined and should be considered as a whole. Each street has a specific purpose or function. This function can be characterized by the level of access to surrounding properties and the length of the trip on that specific roadway. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) functional classification system for urban areas is divided into urban principal arterials, minor arterial streets, collector streets, and local streets. Principal arterials include interstates, expressways, and principal arterials. Eligibility for Federal Highway Administration funding and to provide design standards and access criteria are two important reasons to classify roadway. The region is served by Interstate 15 (north/South) and Interstate 86 (east/west). While classified within the arterial class, they are designated federally and do not change locally. Interstates will be shown in the functional classification map, but they will not be specifically addressed in this report. Functional Classification Update The Idaho Transportation Department has the primary responsibility for developing and updating a statewide highway functional classification in rural and urban areas to determine the functional usage of the existing roads and streets. -

Longer Combination Vehicles on Exclusive Truck Lanes: Interstate 90 Corridor Case Study

Longer Combination Vehicles on Exclusive Truck Lanes: Interstate 90 Corridor Case Study final report prepared for Federal Highway Administration September 2009 final report Longer Combination Vehicles on Exclusive Truck Lanes: Interstate 90 Corridor Case Study prepared for Federal Highway Administration date September 2009 Longer Combination Vehicles on Exclusive Truck Lanes: Interstate 90 Corridor Case Study Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Study Overview .......................................................................................... 1-1 2.0 Research Approach ............................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Analytical Framework ............................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Data Collection and Testing ...................................................................... 2-1 2.3 Outreach ....................................................................................................... 2-2 3.0 Facility Characteristics ....................................................................................... 3-1 3.1 Highway Physical Characteristics ............................................................ 3-1 3.2 Highway Operations .................................................................................. 3-3 3.3 Capital Improvement Costs ..................................................................... -

NORTH I-75 MASTER PLAN Summary Report

NORTH I-75 MASTER PLAN Summary Report Interstate 75 (SR 93) From the Florida’s Turnpike Interchange to the I-10 Interchange Alachua, Bradford, Clay, Citrus, Columbia, Duval, Levy, Marion, and Sumter Counties, Florida Financial Project ID: 191985-2-12-01 June 2017 Updated August 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2 PROJECT BACKGROUND & PURPOSE .................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Background ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 2.2 I-75 Relief Task Force Recommendations ...................................................................................................................................... 2 3 STUDY AREA CORRIDORS ........................................................................................................................................ 4 3.1 Study Area .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 4 STUDY METHODOLOGY & PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT ............................................................................................. 6 5 EXISTING AND FUTURE I-75 TRANSPORTATION ............................................................................................... -

Transportation Element

CHAPTER 3 CITY OF NORTH PORT COMPREHENSIVE PLAN _________________________________ TRANSPORTATION Transportation Element Table of Contents Chapter 3 Transportation Page Introduction 3-3 Transportation Issues Identified in the EAR 3-4 Functional Classification of Roads 3-6 Strategic Intermodal System 3-8 Roadway Jurisdiction and Maintenance 3-8 Parking Facilities 3-8 Traffic Generators 3-9 Traffic Counts 3-10 Intersection Deficiencies 3-10 Roadway Level of Service 3-10 State Highway System Levels of Service 3-11 Existing Level of Service Standards 3-12 Concurrency Management 3-14 Proportionate Fair Share 3-14 Access Management Strategies 3-15 U.S. 41 Corridor Master Plan 3-15 Transportation and Disaster Management 3-16 Future Growth and Transportation Improvements 3-17 Alternative Modes of Transportation 3-20 Intergovernmental Coordination 3-21 List of Illustrations TABLES 3-1 Existing Roadway Classification 3-7 3-2 Existing Roadway Lanes 3-8 3-3 Existing Roadway Jurisdiction 3-8 3-4 Backlogged and Constrained Facilities 3-14 3-5 Time to Clear Landfalling Storm for Evacuation Zones 3-17 Attachment 2007 Existing Traffic Counts Goals, Objectives, & Policies 3-22 Maps follow GOP’s 3-1 Existing & Future Transit Generators 3-5 Existing Roadway Lane Classification 3-2 Existing Roadway Jurisdictional 3-5a Future Roadway Lane Classification 3-2a Future Roadway Jurisdictional 3-6 Future Transportation 3-3 Level of Service 3-3b LOS C Congestion Levels 3-4 Existing Roadway Classification 3-2 Transportation Element TRANSPORTATION ELEMENT INTRODUCTION The goal of the transportation element is to develop an effective multi-modal transportation system which optimizes safety, convenience, cost, and pollution reduction practices by establishing internal and external transportation linkages between residential neighborhoods and activity centers. -

Acre Gas, Food & Lodging Development Opportunity Interstate

New 9+/-Acre Gas, Food & Lodging Development Opportunity Interstate 15 & Dale Evans Parkway Apple Valley, CA Freeway Location Traffic Counts in Excess of 66,000VPD 1 Acre Pads Available, For Sale, Ground Lease or Build-to-Suit Highlights Gateway to Apple Valley Freeway Exposure / Frontage to I-15 in excess of 66,000 VPD Off/On Ramp Location. Located in highly sought after freeway ramp location on I-15 in high desert corridor Interstate I-15 heavily Traveled with Over 2 Million Vehicles Per Month Located 20 Miles South of Barstow/Lenwood, 10 Miles North of Victorville Located in Area with High Demand for Gas, Food and Lodging Conveniently Located Midway Between Southern California and Las Vegas, Nevada Adam Farmer P. (951) 696-2727 Xpresswest Bullet Train from Victorville to Las Vegas plans to Cell. (951) 764-3744 build station across freeway. www.xpresswest.com [email protected] 26856 Adams Ave Suite 200 Murrieta, CA 92562 This information is compiled from data that we believe to be correct but, no liability is assumed by this company as to accuracy of such data Area / I-15 Gateway To Apple Valley Site consists of a 9 acre development at the North East Corner of Dale Evans Parkway and Interstate 15 located in Apple Valley. Site offers freeway frontage, on/off ramp position strategically to capture all traffic traveling on the I-15. Development will offer 9 pad sites available for gas, food, multi tenant and lodging. Interstate 15 runs North and South with traffic counts in excess of 66,000 ADT. Pads will be available for sale, ground lease or build-to-suit. -

Sb1098 Int.Pdf

STATE OF OKLAHOMA 2nd Session of the 47th Legislature (2000) SENATE BILL 1098 By: Helton AS INTRODUCED An Act relating to roads, bridges and ferries; amending 69 O.S. 1991, Section 1705, as last amended by Section 414, Chapter 5, 1st Extraordinary Session, O.S.L. 1999 (69 O.S. Supp. 1999, Section 1705), which relates to the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority; requiring the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority to construct an off ramp on the H.E. Bailey Turnpike at Fletcher, Oklahoma in the vicinity of the Interstate 44 and State Highway 277 intersection; prohibiting the removal and requiring maintenance of certain on or off ramp; and providing an effective date. BE IT ENACTED BY THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA: SECTION 1. AMENDATORY 69 O.S. 1991, Section 1705, as last amended by Section 414, Chapter 5, 1st Extraordinary Session, O.S.L. 1999 (69 O.S. Supp. 1999, Section 1705), is amended to read as follows: Section 1705. The Oklahoma Turnpike Authority is hereby authorized and empowered: (a) To adopt bylaws for the regulation of its affairs and conduct of its business. (b) To adopt an official seal and alter the same at pleasure. (c) To maintain an office at such place or places within the state as it may designate. (d) To sue and be sued in contract, reverse condemnation, equity, mandamus and similar actions in its own name, plead and be impleaded; provided, that any and all actions at law or in equity against the Authority shall be brought in the county in which the principal office of the Authority shall be located, or in the county of the residence of the plaintiff, or the county where the cause of action arose. -

Transportation/4

TRANSPORTATION/4 4.1/OVERVIEW Like the rest of the City, Biloxi’s transportation system was The City of Biloxi is in a rebuilding mode, both to replace aging profoundly impacted by Hurricane Katrina. Prior to Hurricane infrastructure and to repair and improve the roadways and fa- Katrina, the City was experiencing intensive development of cilities that were damaged by Katrina and subsequent storms. coastal properties adjacent to Highway 90, including condo- - minium, casino, and retail projects. Katrina devastated High- lowing reconstruction of U.S. Highway 90, the Biloxi Bridge, way 90 and other key transportation facilities, highlighting andPre-Katrina casinos. traffic Many volumes transportation and congestion projects haveare in returned progress fol or Biloxi’s dependence on a constrained network of roadways under consideration, providing an opportunity for coordinat- and bridges connecting to inland areas. ed, long-range planning for a system that supports the future The City of Biloxi operated in a State of Emergency for over land use and development pattern of Biloxi. In that context, two years following Hurricane Katrina’s landfall on August 29, the Transportation Element of the Comprehensive Plan lays 2005. Roadway access to the Biloxi Peninsula is provided by out a strategy to develop a multi-modal system that improves Highway 90 and Pass Road from the west and by three key mobility and safety and increases the choices available to resi- bridges from the east and north: Highway 90 via the Biloxi dents and visitors to move about the City. Bay Bridge from Oceans Springs and I-110 and Popp’s Ferry Road over Back Bay. -

An Investigation Into the Use of Road Drainage Structures by Wildlife in Maryland

MD-11-SP909B4M STATE HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION RESEARCH REPORT AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE USE OF ROAD DRAINAGE STRUCTURES BY WILDLIFE IN MARYLAND J. Edward Gates James L. Sparks, Jr. University Of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Appalachian Laboratory Project number SP808B4Q (Phase I) SP909B4M (Phase II) FINAL REPORT August 2011 Culvert Use by Wildlife MD-11-SP909B4M Page 2 of 72 The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Maryland State Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Culvert Use by Wildlife MD-11-SP909B4M Page 3 of 72 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. MD-11-SP909B4M 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date An Investigation into the Use of Road Drainage Structures by Wildlife in August, 2011 Maryland 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author/s 8. Performing Organization Report No. James L. Sparks, Jr. and J. Edward Gates 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) University Of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Appalachian Laboratory 11. Contract or Grant No. 301 Braddock Road Phase I: SP808B4Q Frostburg, Maryland 21532 Phase II: SP909B4M 12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Maryland State Highway Administration Office of Policy & Research Final Report 707 North Calvert Street 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Baltimore MD 21202 (7120) STMD - MDOT/SHA 15. -

Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project

Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project I-5 North Coast Corridor Project Final EIR/EIS page L-1 Appendix L: Design Guidelines: I-5 NCC Project I-5 North Coast Corridor Project Final EIR/EIS page L-2 Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project September 2013 Prepared by: Caltrans District 11 | T.Y. Lin International | Safdie Rabines Architects | Estrada Land Planning Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project Prepared by: Caltrans District 11 4050 Taylor Street San Diego, CA 92110 T.Y. Lin International 404 Camino del Rio South, Suite 700 San Diego, CA 92108 | 619.692.1920 Safdie Rabines Architects 925 Ft. Stockton Drive San Diego, CA 92123 | 619.297.6153 Estrada Land Planning 755 Broadway Circle, Suite 300 San Diego, CA 92101 | 619.236.0143 Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project – Design Guidelines Table of Contents Design Guidelines Interstate 5 North Coast Corridor Project Table of Contents I. Project Background D. Design Themes....................17 vi. Typical Freeway Undercrossing. 36 vii. Typical Bridge Details. 37 A. Introduction....................1 i. Corridor Theme Elements. 17 ii. Corridor Theme Priorities. 19 - Southern Bluff Theme....................38 B. Purpose.......................1 - Coastal Mesa Theme.....................39 iii. Corridor Theme Units. 20 C. Components & Products. 1 - Northern Urban Theme. 40 - Southern Bluff Theme....................21 D. The Proposed Project. 2 - Coastal Mesa Theme.....................22 B. Walls.............................41 E. Previous Relevant Documents. 3 - Northern Urban Theme. 23 i. Theme Unit Specific Wall Concepts. -

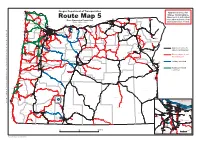

Route Map 5 Ä H339 Æ

ASTORIA Oregon Department of Transportation Warrenton H104 Svensen Approved routes for Mayger 30 Westport ¤£ Clatskanie Æ 101 Olney Ä Rainier ¤£ H105 Triples Combinations. Æ Gearhart C L A T S O PÄ 47 Prescott SEASIDE Goble H332 202 Mist 73300 Movement is authorized 395 Umapine Necanicum Cold ¤£2 Jewell ¤£ Springs Jct. C O L U M B I A Æ Ä MP 9.76 Umatilla Jct. Milton-Freewater Flora Ä Æ Æ Cannon Beach Route Map 5 Ä H339 Æ H103 Pittsburg Irrigon Ä only under authority of an Columbia City Æ Over-Dimension Permit Unit Ä Elsie 47 730 Holdman 53 ST. HELENS ¤£ Helix 11 Vernonia Boardman 0 207 26 7 30 82 Athena Æ ¤£ Ä Over-Dimension Permit. ¤£ Revised March 2020 HERMISTON 3 ¨¦§ H Heppner Jct. Æ Ä H334 Weston Scappoose Stanfield 3 Nehalem 3 Adams 204 Manzanita HOOD Permission not granted to 5 RIVER cross RR crossing at MP 102.40 30 37 Æ 84 30 Echo Ä Wheeler Buxton £ in Hood River 84 ¤£ Arlington H W A L L O W A ¤ 3 Cascade ¨¦§ Biggs § MP 13.22 ¨¦ 26 Locks Jct. Rufus 3 Æ Rockaway Celilo Blalock Ä H320 1 Æ T I L L A M O O K ¤£ Mosier Ä 82 Beach Banks North H281 PENDLETON Plains PORTLAND Æ Ä Minam Imnaha Odell Wallowa Æ Ä 74 Garibaldi Wasco 207 W A S H I N G T O N The Elgin . Bay City Troutdale Multnomah Æ CorneliusÄ Fairview Dalles t Forest HILLSBORO H O O D H282 206 i 6 Grove Falls G I L L I A M Wood 84 Oceanside Beaverton R I V E R U M A T I L L A Summerville m H131 Village Ione r 8 ¨¦§ Lostine Æ Parkdale 197 Ä Gresham Moro 0 e Tillamook M U L T N O M A H MP 83.00 ¤£ 30 Imbler 5 Netarts ENTERPRISE Æ Ä Pilot 3 Æ Ä £ Æ Ä ¤ p Æ Ä Rock H Gaston Tigard