Chapter Five: Case Study Methven: the Gateway Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

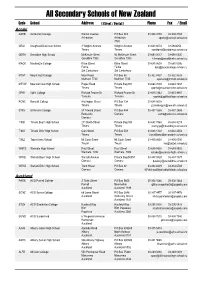

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Download Download

A YEN FOR THE DOLLAR: Airlines and the Transformation of US-Japanese Tourism, 1947-1 977 Douglas Karsner Department of History Bloomsburg University This article examines the transformation of transpacific tourism between the United States and Japan from 1947 to 1977, focusing on the key role that Pan American World Airways, Northwest Orient Airlines, and Japan Airlines played in this development. In the late 1940s, travel was mostly by a small upper class leisure market cruising on ships. Linkages between the air carriers and other factors, including governmental policy, travel organizations, and changes in business and culture influenced the industry. By the 1970s, these elements had reshaped the nature and geography of tourism, into a mass airline tourist market characterized by package tours, special interest trips, and consumer values. Between 1947 and 1977, several factors helped transform the nature of transpacific tourism between the United States and Japan. Pan American Airways, Northwest Airlines, and Japan Airlines played crucial roles in this development. These airline companies employed various marketing strategies, worked with travel associations, tapped into expanding consumer values, and pressured governments. Simultaneously, decisions made by tourist organizations, consumers, and especially governments also shaped this process. The evolution of transpacific tourism occurred in three stages, growing slowly from 1947 to 1954, accelerating in the period to 1964, and finally developing into a mass leisure market by the 1970s.’ When the US State Department officially permitted Pan American Airways and Northwest Airlines to start offering regularly scheduled service to Japan in August 1947, few American tourists wanted to make the journey. This was largely because they would have had to obtain a passport from the State Department and a certificate from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. -

Nitrate Contamination of Groundwater in the Ashburton-Hinds Plain

Nitrate contamination and groundwater chemistry – Ashburton-Hinds plain Report No. R10/143 ISBN 978-1-927146-01-9 (printed) ISBN 978-1-927161-28-9 (electronic) Carl Hanson and Phil Abraham May 2010 Report R10/143 ISBN 978-1-927146-01-9 (printed) ISBN 978-1-927161-28-9 (electronic) 58 Kilmore Street PO Box 345 Christchurch 8140 Phone (03) 365 3828 Fax (03) 365 3194 75 Church Street PO Box 550 Timaru 7940 Phone (03) 687 7800 Fax (03) 687 7808 Website: www.ecan.govt.nz Customer Services Phone 0800 324 636 Nitrate contamination and groundwater chemistry - Ashburton-Hinds plain Executive summary The Ashburton-Hinds plain is the sector of the Canterbury Plains that lies between the Ashburton River/Hakatere and the Hinds River. It is an area dominated by agriculture, with a mixture of cropping and grazing, both irrigated and non-irrigated. This report presents the results from a number investigations conducted in 2004 to create a snapshot of nitrate concentrations in groundwater across the Ashburton-Hinds plain. It then examines data that have been collected since 2004 to update the conclusions drawn from the 2004 data. In 2004, nitrate nitrogen concentrations were measured in groundwater samples from 121 wells on the Ashburton-Hinds plain. The concentrations ranged from less than 0.1 milligram per litre (mg/L) to more than 22 mg/L. The highest concentrations were measured in the Tinwald area, within an area approximately 3 km wide and 11 km long where concentrations were commonly greater than the maximum acceptable value (MAV) of 11.3 mg/L set by the Ministry of Health. -

Environmental Assessment and Review Framework IND

Infrastructure Development Investment Program for Tourism (RRP IND 40648) Environmental Assessment and Review Framework Document Stage: Draft for Consultation Project Number: P40648 July 2010 IND: Infrastructure Development Investment Program for Tourism The environmental assessment and review framework is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. I. Introduction A. Project Background 1. The India Infrastructure Development Investment Program for Tourism (IDIPT) envisages an environmentally and culturally sustainable and socially inclusive tourism development, in the project states of Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Tamil Nadu and Uttarakhand. The project uses a sector loan approach through a multitranche financing facility modality likely in five tranches planned from 2011-2020. The expected impact of the Project in the four states is sustainable and inclusive tourism development in priority State tourism sub circuits divided into marketable cluster destinations that exhibit enhanced protection and management of key natural and cultural heritage tourism sites, improved market connectivity, enhanced destination and site environment and tourist support infrastructure, and enhanced capacities for sustainable destination and site development with extensive participation by the private sector and local communities. The investment program outputs will be (i) improved basic urban infrastructure (such as water supply, -

Final Report on a Pre-Feasibility Study Into an Antarctic Gateway Facility in Cape Town

ABCD Department of Science and Technology Final Report on a Pre-Feasibility Study into an Antarctic Gateway facility in Cape Town January 2007 This report contains 103 pages DST final report © 2006 KPMG Services (Proprietary) Limited, a South African company and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International, a Swiss cooperative. All rights reserved. ABCD Department of Science and Technology Final Report on a Pre-Feasibility Study into an Antarctic Gateway facility in Cape Town January 2007 Contents Executive Summary 1 1 Terms of Reference 5 2 Description of study approach 5 3 Background 6 3.1 Human activity on the Antarctic continent 6 3.2 The Importance of the Antarctic 7 3.3 Logistics 7 3.3.1 Ship operations 8 3.3.2 Air transport 12 4 Benchmarking to Other Antarctic Gateway Cities 13 4.1 Hobart, Tasmania (Australia) 14 4.2 Ushuaia (Argentina) 18 4.3 Punta Arenas (Chile) 19 4.4 Scientific Interests 20 4.5 Tourism 22 4.6 Education and Awareness 24 4.7 Commerce 25 4.8 Industry 28 4.9 Growth opportunity 32 5 A Cape-Antarctic Gateway: Concept Development 33 5.1.1 Cape Town as a Unique Gateway 34 5.1.2 Institutional Considerations 35 5.1.3 Facility Alternatives 36 5.1.4 Rationale for an Antarctic Visitor Centre 37 5.1.5 Assessment of Site Alternatives for a Visitor Centre 37 5.1.6 Conclusion on Site Assessment 44 6 Assessment of alternatives within the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront (Optimal site alternative for a Visitor Centre) 45 7 Assessment of Facility Alternatives: Logistical Support to National Antarctic Programmes (NAP’s) 55 8 Conclusions and Suggestions 58 9 Appendix A: Interview Notes 59 i © 2007 KPMG Services (Proprietary) Limited. -

As the Nzski CEO James Coddington Looked out Over the Spectacular Vista Afforded by the Remarkables

NZSki “Life As It Ought To Be” As the NZSki CEO James Coddington looked out over the spectacular vista afforded by the Remarkables mountain range - taking in the New Zealand tourist hub of Queenstown - he contemplated the future for his company. “We’re at a tipping point,” he suggested, “things could go either way. We’ve been gradually building momentum over the last few years. But we have to keep moving forward. We certainly have room to cope with more skiers, but if all we do is get more skiers on the mountains we will actually reduce the customer experience from what it is now. That will mean less skiers in the future, a weakened brand, and the undoing of a lot of good work over the last few years.” Figure 1: New Zealand’s Ski Areas NZSki operated 3 skifields – Coronet Peak and the Remarkables in Queenstown and Mount Hutt in Canterbury. Recent growth since Coddington’s appointment in 2007 has been spectacular. The 2009 season was the most successful season on record. As a company, skier/rider numbers were up 29% over 2008 and revenue was up 22% - despite the economic recession. “When I began we were getting 180,000 – 200,000 people a year on Coronet Peak, but now we’re at 330,000. The biggest single day in 2007 saw around 4000 people, but this year we had 7777 people in one day. With our old infrastructure we simply couldn’t have coped – but the completely rebuilt base building, and completion of the snowmaking system and our investments in lift and pass technology have paid huge dividends in protecting the experience. -

Recco® Detectors Worldwide

RECCO® DETECTORS WORLDWIDE ANDORRA Krimml, Salzburg Aflenz, ÖBRD Steiermark Krippenstein/Obertraun, Aigen im Ennstal, ÖBRD Steiermark Arcalis Oberösterreich Alpbach, ÖBRD Tirol Arinsal Kössen, Tirol Althofen-Hemmaland, ÖBRD Grau Roig Lech, Tirol Kärnten Pas de la Casa Leogang, Salzburg Altausee, ÖBRD Steiermark Soldeu Loser-Sandling, Steiermark Altenmarkt, ÖBRD Salzburg Mayrhofen (Zillertal), Tirol Axams, ÖBRD Tirol HELICOPTER BASES & SAR Mellau, Vorarlberg Bad Hofgastein, ÖBRD Salzburg BOMBERS Murau/Kreischberg, Steiermark Bischofshofen, ÖBRD Salzburg Andorra La Vella Mölltaler Gletscher, Kärnten Bludenz, ÖBRD Vorarlberg Nassfeld-Hermagor, Kärnten Eisenerz, ÖBRD Steiermark ARGENTINA Nauders am Reschenpass, Tirol Flachau, ÖBRD Salzburg Bariloche Nordkette Innsbruck, Tirol Fragant, ÖBRD Kärnten La Hoya Obergurgl/Hochgurgl, Tirol Fulpmes/Schlick, ÖBRD Tirol Las Lenas Pitztaler Gletscher-Riffelsee, Tirol Fusch, ÖBRD Salzburg Penitentes Planneralm, Steiermark Galtür, ÖBRD Tirol Präbichl, Steiermark Gaschurn, ÖBRD Vorarlberg AUSTRALIA Rauris, Salzburg Gesäuse, Admont, ÖBRD Steiermark Riesneralm, Steiermark Golling, ÖBRD Salzburg Mount Hotham, Victoria Saalbach-Hinterglemm, Salzburg Gries/Sellrain, ÖBRD Tirol Scheffau-Wilder Kaiser, Tirol Gröbming, ÖBRD Steiermark Schiarena Präbichl, Steiermark Heiligenblut, ÖBRD Kärnten AUSTRIA Schladming, Steiermark Judenburg, ÖBRD Steiermark Aberg Maria Alm, Salzburg Schoppernau, Vorarlberg Kaltenbach Hochzillertal, ÖBRD Tirol Achenkirch Christlum, Tirol Schönberg-Lachtal, Steiermark Kaprun, ÖBRD Salzburg -

2019 Alpine Competition Rules

2021 ALPINE COMPETITION RULES SNOW SPORTS NEW ZEALAND 78 ANDERSON ROAD, WANAKA, OTAGO, NEW ZEALAND PO Box 395, Wanaka +64 (0) 3 443 4085 www.snowsports.co.nz [email protected] On the cover NZ Ski Team Member Alice Robinson Cortina World Championship 2021 Contents 1. Introduction ..........................................................................................................7 2 1.1 The Objectives of this Rulebook ...................................................................7 1.2 New Zealand’s Alpine Ski Racing History ......................................................7 1.3 About Snow Sports NZ .................................................................................7 1.4 SSNZ Alpine Mission ....................................................................................8 1.5 Alpine Sport Committee ...............................................................................8 1.6 FIS ................................................................................................................8 1.7 ICR ...............................................................................................................8 1.8 NZCR ............................................................................................................8 1.9 World Para Alpine Skiing ..............................................................................8 2. Membership and Age Group Classifications 2021 ..................................................9 3. Athlete Registration ........................................................................................... -

UV Exposure on New Zealand Ski-Fields M

UV exposure on New Zealand ski-fields M. Allen Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Canterbury, Private Bag, Christchurch, New Zealand R.L. McKenzie National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, NIWA, Lauder, Central Otago, New Zealand Abstract. UV exposures measured during a measurement 1. The UVI on the ski-field was 20-30% greater than campaign at Mt Hutt Skifield in 2003 are compared with at sea-level. those from a more extensive campaign in 2005. The results 2. Over the period of the ski season there are rapid from the skifield are also compared with those received increases in peak UVI. during a round of golf in the summer at nearby courses. 3. UV intensities were often significantly greater The overall conclusions are similar to those from the 2003 than on horizontal surfaces. study. The UV exposures are sensitive to the location of 4. Peak UV intensities during these ski days are less the sensor, and the total dose received during skiing is than at sea level in summer. similar to that received during a round of golf in summer. The first study was limited to a single anatomical site on Introduction one subject (M Allen). Here we describe the results of a follow-up study that included more sensors located at UV dosimeter badges were recently developed to different anatomical sites on several individuals. The study monitor personal exposures to UV radiation. They was also supported by having similar sensors mounted comprise a miniaturised detector designed to measure horizontally at the top and bottom of the ski field, and at a erythemally-weighted UV radiation. -

![Detailed Itinerary [ID: 917]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4829/detailed-itinerary-id-917-934829.webp)

Detailed Itinerary [ID: 917]

Any I Travel 0064 3 3799689 www.anyitravel.com 12 day Epic South Island Ski Tour Starting in Christchurch and finishing in Queenstown, spend 12 days touring the South Island ski fields with 5 days skiing or snowboarding and 5 days of rental equipment included! Get your snow fix and enjoy plenty of extra leisure time to explore the different regions of the south and maybe throw in an adventure activity or two! Starts in: Christchurch Finishes in: Queenstown Length: 12days / 11nights Accommodation: Motels Can be customised: Yes This itinerary can be customised to suit you perfectly. We can add more days, remove days, change accommodations, mix it up, add activities to suit your interests or simply design and create something from scratch. Call us today to get your custom New Zealand itinerary underway. Inclusions: Includes: Late model rental cars Includes: Fully inclusive rental car insurance (excess may apply) Includes: Unlimited kms Includes: GPS navigation Includes: Airport & ferry terminal rental car fees Includes: Additional drivers Includes: Comprehensive tour pack (detailed Includes: 24/7 support while touring New Zealand itinerary, driving instructions, map/guidebooks, brochures) Included activity: NZSki: Equipment Rental Included activity: NZSki New Zealand Superpass: 1 Day Lift Pass Included activity: NZSki: Equipment Rental Included activity: Tekapo Springs Hot Pools Included activity: Roundhill Ski Field 1 Day Lift Included activity: Roundhill Ski Field Rental Pass Equipment Included activity: Cardrona & Treble Cone ski Included activity: NZSki New Zealand Superpass: field 1 Day Lift Pass and Rental Package 2 Day Lift Pass Included activity: NZSki: Equipment Rental For a detailed copy of this itinerary go to http://anyitravel.nzwt.co.nz/tour.php?tour_id=917 or call us on 0064 3 3799689 Day 1 Collect your rental car This tour can be priced with any of the rental cars available in our fantastic range, from economy hatchbacks to prestige saloons and SUV's. -

Vietnam Tourist Information Centre Guide TABLE of CONTENTS

MINISTRY OF CULTURE, SPORTS AND TOURISM VIETNAM NATIONAL ADMINISTRATION OF TOURISM ENVIRONMENTALLY AND SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE TOURISM CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FUNDED BY THE EUROPEAN UNION Vietnam tourist information centre guide TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND TO THE GUIDE 3 INTRODUCTION TO TOURISM INFORMATION CENTRES 5 The need for Tourist Information Centres 5 The market for Tourist Information Centres 5 The functions of Tourist Information Centres 6 Tourist Information Centres in Vietnam 7 PLANNING FOR TOURIST INFORMATION CENTRES 8 Selecting a suitable location 8 Determining the scope 9 Design and layout 10 Facilities and equipment 14 Signage 16 TOURIST INFORMATION CENTRE OPERATIONS AND MANGEMENT 20 Delivering good customer service 20 Presentation and hygiene 29 Human resources 30 Office administration 33 Funding Tourist Information Centre operation 36 Building partnerships 38 BIBLIOGRAPHY AND REFERENCES 40 Programme Implementation Unit: Room 402, 4th Floor, Vinaplast - Tai Tam Building 39A Ngo Quyen Street, Hanoi, Vietnam Tel: (84 4) 3734 9357 / 3734 9358 | Fax: (84 4) 3734 9359 | E-mail: [email protected] | Website: www.esrt.vn © 2013 Environmentally and Socially Responsible Tourism Capacity Development Programme This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union funded Environmentally and Socially Responsible Tourism Capacity Development Programme (ESRT). The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the ESRT programme and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The European Union and ESRT do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accept no responsibility for any consequence of their use. ESRT and the EU encourage printing or copying exclusively for personal and non-commercial use with proper acknowledgement of ESRT and the EU. -

Protected Areas, the Tourist Bubble and Regional Economic Development Julius Arnegger Protected Areas, the Tourist Bubble and Regional Economic Development

Würzburger Geographische Arbeiten WGA GGW 110 Würzburger Geographische Gesellschaft Würzburg Based on demand-side surveys and income multipli- ers, this study analyzes the structure and economic Geographische importance of tourism in two highly frequented protected areas, the Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve in Arbeiten Mexico (SKBR) and the Souss-Massa National Park (SMNP) in Morocco. With regional income effects of approximately 1 million USD (SKBR) and approximately 1.9 million USD (SMNP), both the SKBR and the SMNP play important roles for the regional economies in underdeveloped rural regions. Visitor structures are heterogeneous: with regard to planning and marketing of nature-based tourism, protected area managers and political decision-takers are advised put a stronger focus on ecologically and economically attractive visitor groups. Julius Arnegger Protected Areas, the Tourist Bubble and Regional Economic Development Julius Arnegger Protected Areas, the Tourist Bubble and Regional Economic Development ISBN 978-3-95826-000-9 Würzburg University Press Band 110 Julius Arnegger Protected Areas, the Tourist Bubble and Regional Economic Development WÜRZBURGER GEOGRAPHISCHE ARBEITEN Mitteilungen der Geographischen Gesellschaft Würzburg Herausgeber R. Baumhauer, B. Hahn, H. Job, H. Paeth, J. Rauh, B. Terhorst Band 110 Die Schriftenreihe Würzburger Geographische Arbeiten wird vom Institut für Geographie und Geologie zusammen mit der Geographischen Gesell- schaft herausgegeben. Die Beiträge umfassen mit wirtschafts-, sozial- und naturwissenschaftlichen Forschungsperspektiven die gesamte thematische Bandbreite der Geographie. Der erste Band der Reihe wurde bereits 1953 herausgegeben. Julius Arnegger Protected Areas, the Tourist Bubble and Regional Economic Development Two Case Studies from Mexico and Morocco Würzburger Geographische Arbeiten Herausgegeben vom Institut für Geographie und Geologie der Universität Würzburg in Verbindung mit der Geographischen Gesellschaft Würzburg Herausgeber R.