88 - Upper Oconee Water Trails Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morrone, Michele Directo

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 417 064 SE 061 114 AUTHOR Mourad, Teresa; Morrone, Michele TITLE Directory of Ohio Environmental Education Sites and Resources. INSTITUTION Environmental Education Council of Ohio, Akron. SPONS AGENCY Ohio State Environmental Protection Agency, Columbus. PUB DATE 1997-12-00 NOTE 145p. AVAILABLE FROM Environmental Education Council of Ohio, P.O. Box 2911, Akron, OH 44309-2911; or Ohio Environmental Education Fund, Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, P.O. Box 1049, Columbus, OH 43216-1049. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Agencies; Conservation Education; Curriculum Enrichment; Ecology; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; *Environmental Education; *Experiential Learning; *Field Trips; Hands on Science; History Instruction; Learning Activities; Museums; Nature Centers; *Outdoor Education; Parks; Planetariums; Recreational Facilities; *Science Teaching Centers; Social Studies; Zoos IDENTIFIERS Gardens; Ohio ABSTRACT This publication is the result of a collaboration between the Environmental Education Council of Ohio (EECO) and the Office of Environmental Education at the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (OEPA). This directory of environmental education resources within the state of Ohio is intended to assist educators in finding information that can complement local curricula and programs. The directory is divided into three sections. Section I contains information on local environmental education sites and resources. These are grouped by EECO region, alphabetized by county, and further alphabetized by organization name. Resources range from arboretums to zoos. Section II lists resources available at a statewide level. These include state and federal government agencies, environmental education organizations and programs, and resource persons. Section III contains cross-referenced lists of Section I by organization name, audience, organization type, and programs and services to help educators identify local resources. -

Life's More Than a Walk in a Park

Ann arbor parks & recreation 2018 SPRING/SUMMER ACTIVITY GUIDE life’s more than a walk in a park. REGISTER ONLINE: WWW.A2GOV.ORG/PARKSREGISTER OR IN PERSON AT ANY PARKS FACILITY INCLUDING OUR CUSTOMER SERVICE CENTER AT COBBLESTONE FARM PAGE 1 | Together, we enrich life by cultivating exceptional experiences | a2gov.org/parks Table of Contents 2017-18 Millage Projects ................................................................... page 61 Adopt-a-Park ................................................................................. page 51 Ann Arbor Farmers Market ............................................................... page 24 Ann Arbor Senior Center ................................................................ page 14 Argo & Gallup Canoe Liveries ........................................................ page 19 A2Fix It Program .............................................................................. page 57 Bryant & Northside Community Centers ....................................... page 56 Buhr Park Outdoor Pool ................................................................... page 43 Concerts in the Park ....................................................................... page 05 Cobblestone Farm ........................................................................... page 62 Cobblestone Farm Association ..................................................... page 59 FootGolf at Huron Hills ............................................................... page 29 Forestry & Park and Public Space Maintenance ...................... -

Ntr Inc. Canoe Livery Bolivar, Ohio Rental Agreement and Parental Release

NTR INC. CANOE LIVERY BOLIVAR, OHIO RENTAL AGREEMENT AND PARENTAL RELEASE Welcome to NTR Canoe Livery. As you set out on a scenic journey upon this historic river, please realize that canoeing, kayaking, and tubing, as any adventure, entails some risks and hazards, and can result in injury or death. A canoe by its very nature sacrifices balance for speed and sleekness, and the occupants must take care to maintain a center of balance and keep the canoe lined up with the current. Obstacles in the river represent possible hazards and should be respected. Changing river conditions at times result in quick currents, and the necessity for alert and responsible operation of the canoe. Please examine your equipment and report any problems before beginning your trip. Wear your life jacket. Please return equipment in the same condition as when received. In consideration of my use of property and equipment of Nature Trail’s Rental, and with full knowledge of the risks and hazards involved in the use thereof, I voluntarily assume all risk of loss, damage, or injury that may be sustained to me personally or those in my custody and/or to my property and hereby do release Nature Trails’ Rental and its agents from all claims, demands, actions, causes of action, and from all liability for damage, loss or injury of whatsoever kind, nature or description that I may sustain during the transportation and/or use of the equipment and property of Nature Trail’s Rental I agree to pay Nature Rental for any damage to, or loss of, equipment that may occur during the rental period. -

Athens Campus

Athens Campus Athens Campus Introduction The University of Georgia is centered around the town of Athens, located approximately 60 miles northeast of the capital of Atlanta, Georgia. The University was incorporated by an act of the General Assembly on January 25, 1785, as the first state-chartered and supported college in the United States. The campus began to take physical form after a 633-acre parcel of land was donated for this purpose in 1801. The university’s first building—Franklin College, now Old College—was completed in 1806. Initially a liberal-arts focused college, University of Georgia remained modest in size and grew slowly during the Figure 48. Emblem of the antebellum years of the nineteenth century. In 1862, passage of the Morrill Act University of Georgia. by Congress would eventually lead to dramatic changes in the focus, curriculum, and educational opportunities afforded at the University of Georgia. The Morrill Act authorized the establishment of a system of land grant colleges, which supported, among other initiatives, agricultural education within the United States. The University of Georgia began to receive federal funds as a land grant college in 1872 and to offer instruction in agriculture and mechanical arts. The role of agricultural education and research has continued to grow ever since, and is now supported by experiment stations, 4-H centers, and marine institutes located throughout the state. The Athens campus forms the heart of the University of Georgia’s educational program. The university is composed of seventeen colleges and schools, some of which include auxiliary divisions that offer teaching, research, and service activities. -

Cole Canoe Base Leader's Manual

Featured in September– October 2015 Article Editor: Bryan Wendell Photo credit: W. Garth Dowling Cole Canoe Base Leader’s Manual Table of Contents Page Welcome from Camp Director; Gus Chutorash 5 Mission Statement 6 Aims & Methods 7 Fees, Payment Schedules and Incentives 8 Campership Assistance 9 Equipment 11 What your Scouts should bring to camp 12 Roles and Responsibilities 13 Health and Safety 15 Policies and Regulations 15 Bike Safety 17 Youth Protection 19 S.T.E.M Program 21 Ranger’s Corner 22 Order of the Arrow 23 Other Important Camp Information 25 What is Edward N. Cole Canoe Base 28 History of Edward N. Cole Canoe Base 29 Check-In and First Day Outline 30 The Sunday Program 30 The Program at Cole Canoe Base Merit Badge Program Areas 31 Aquatics Program / Swim Checks 31 Outdoor Skills & First Year Camper Program 32 Ecology / Conservation (Eco/Con) 32 Climbing, Repelling, Zipline 32 Shooting Sports & Handicraft Program 33 Specialty Merit Badges [Main Street USA, Cosgro Productions] 33 Hunter & Boater Safety 34 Please note: All of this, and additional information can be found at www.michiganscouting.org 2 Table of Contents (Cont.) Page Suggested Camper Schedule 35 Merit Badge Prerequisites 36 Aquatics 37 Outdoor Skills 39 Ecology / Conservation [Eco/Con] 41 Shooting Sports Program 44 Craft Program 45 Specialty Merit Badges 46 Camp-wide Activities 49 High Adventure Programs River Program 51 Upper Peninsula 55 Experience Tells Us 56 How to get to Cole Canoe Base 57 Map of Cole Canoe Base 58 Map of Cole Canoe Base Nature Trails 59 Rifle River Upper Run Map 60 Rifle River Lower Run Map 61 3 Dear Valued Unit Leader: The Summer Camp season is quickly approaching, and the summer camp staff is looking forward to another fantastic year at Cole Canoe Base! We are excited to have you attending Cole, which is now one in a network of four Michigan Crossroads Council (“MCC”) Residential Boy Scout Camps. -

Post-Secondary Nominee Presentation Form U.S. Department of Education Green Ribbon Schools Postsecondary 2015-2018

Post-Secondary Nominee Presentation Form ELIGIBILITY CERTIFICATIONS College or University Certifications The signature of college or university President (or equivalent) on the next page certifies that each of the statements below concerning the institution’s eligibility and compliance with the following requirements is true and correct to the best of their knowledge. 1. The college or university has been evaluated and selected from among institutions within the Nominating Authority’s jurisdiction, based on high achievement in the three ED-GRS Pillars: 1) reduced environmental impact and costs; 2) improved health and wellness; and 3) effective environmental and sustainability education. 2. The college or university is providing the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights (OCR) access to information necessary to investigate a civil rights complaint or to conduct a compliance review. 3. OCR has not issued a violation letter of findings to the college or university concluding that the nominated college or university has violated one or more of the civil rights statutes. A violation letter of findings will not be considered outstanding if OCR has accepted a corrective action plan to remedy the violation. 4. The U.S. Department of Justice does not have a pending suit alleging that the college or university has violated one or more of the civil rights statutes or the Constitution’s equal protection clause. 5. There are no findings by Federal Student Aid of violations in respect to the administration of Title IV student aid funds. 6. The college or university is in good standing with its regional or national accreditor. -

University of Georgia Historical Background

University of Georgia Historical Background A Brief History of the University of Georgia Et docere et rerum exquirere causas. To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things. – University of Georgia motto Figure 2. Campus Map, 1899. (Source: University of Georgia) The history of the University of Georgia (UGA) generally parallels that of the State of Georgia itself. Georgia became the fourth state of the United States after voting to ratify the Constitution on January 2, 1788. Statehood closely followed the Georgia General Assembly’s establishment of UGA in 1785, the first chartered state university in the nation. After approval of the charter, the legislature appointed governing boards and a president, Abraham Baldwin. It would take sixteen years to navigate the challenges associated with securing support, funding, and a location for the new school before students could be admitted in 1801.9 For much of its history, UGA has supported the evolving 9. F. N. Boney, A Pictorial History of The University of Georgia, second edition (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1984), 2–3. University of Georgia Historic Preservation Master Plan 9 University of Georgia Historical Background educational and vocational training needs of the citizenry of the state of Georgia, over time becoming closely tied to innovation in agriculture and scientific research. The information provided below offers a brief overview of UGA’s history, encompassing development of the Athens campus as well as the various other historic properties that support University programs and activities. It is followed by the identification of historic contexts within which the University’s historic properties may be better understood. -

2017 National Veterinary Scholars Symposium 18Th Annual August 4

2017 National Veterinary Scholars Symposium 18th Annual August – 4 5, 2017 Natcher Conference Center, Building 45 National Institutes of Health Bethesda, Maryland Center for Cancer Research National Cancer Institute with The Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges https://www.cancer.gov/ Table of Contents 2017 National Veterinary Scholars Symposium Program Booklet Welcome .............................................................................................................................. 1 NIH Bethesda Campus Visitor Information and Maps .........................................................2 History of the National Institutes of Health ......................................................................... 4 Sponsors ............................................................................................................................... 5 Symposium Agenda .......................................................................................................6 Bios of Speakers ................................................................................................................. 12 Bios of Award Presenters and Recipients ........................................................................... 27 Training Opportunities at the NIH ...................................................................................... 34 Abstracts Listed Alphabetically .......................................................................................... 41 Symposium Participants by College of Veterinary Medicine -

*: Completely Photo Christopher Smith

r - Sometlr inq *: Completely Photo Christopher Smith Within a month I had one like it. Ex- cept mine had prettier graphics... for a while. It also seemed to have a mind of its People in Glass own. Oh, it was a willful critter, seemingly bent on self destruction! It was summer and water levels were low, so I had to bulldog my sassy new glass boat on the Upper Yough. On those steep, technical waters I soon [Shouldn't Throw found out why paddling glass makes you improve. It's not the glass that makes you Stones) better... it's the rocks! And, as luck would have it, on the very night I bought my new boat there was a I paddled plastic for more than ten meteor shower over Western Maryland and years before I bought my first glass boat. thousands of new clunkers were dumped The pressure to switch to glass was in- into the river! tense, since I did most of my boating on The boat that I had purchased had the Yough and Cheat drainage, the stomp- been built specifically for me, with hun- ing grounds of the Snyder brothers and dreds of layers of kevlar and even more Jesse Widdemore. During those days all over the sharp chines and ends. The guy the really hot boaters paddled glass. that built it had seen me on the river, so he I must have been teased a million made my kayak as strong and durable as times that "Plastic keeps turkeys fresh" drift any glass boat could be. -

Blue's Canoe Livery Release Form (Pdf)

PARTICIPATION, RELEASE AND INDEMNIFICATION AGREEMENT IMPORTANT. PLEASE READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY BEFORE SIGNING. THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS A RELEASE OF LIABILITY AND A WAIVER OF CERTAIN LEGAL RIGHTS. In consideration of the opportunity to rent or otherwise use certain equipment and/or participate in activities offered by BLUES CANOE LIVERY, I AGREE ON BEHALF OF MYSELF, AND ON BEHALF OF ALL MINORS FOR WHOM I AM PARENT OR GUARDIAN, TO THE TERMS OF THIS PARTICIPATION AGREEMENT, THE WAIVER AND RELEASE. BLUE RECREATION COMPANY, INC. d/b/a BLUES CANOE LIVERY provides services which may include renting equipment for rafting, canoeing, kayaking, tubing and other outdoor pursuits. BLUES CANOE LIVERY may also provide life jackets, personal flotation devices, camping facilities, shower and bathroom facilities, volleyball courts, and other outdoor related facilities. BLUES CANOE LIVERY may also provide transportation by bus, van or other vehicle to any of these activities. I UNDERSTAND THAT THERE ARE RISKS, HAZARDS AND DANGERS ASSOCIATED WITH THE SERVICES AND ACTIVITIES PROVIDED BY BLUES CANOE LIVERY. These risks include, but are not limited to, the risk of falling out of a canoe, raft, tube or kayak and being injured or killed, or being wet, cold and uncomfortable. These risks include the uncertainties of the river or of the weather, hazards in the river, collisions while traveling by vehicle or on the river, altercations with other people on the river, including altercations with other participants in the same activity, and with the uncertainty of conditions in an outdoor environment. I understand that the description of these risks is not complete and that other unknown or unanticipated risks may result in injury or death. -

Paddling Trails Leave No Trace Principles 5

This brochure made possible by: Florida Paddling Trails Leave No Trace Principles 5. Watch for motorboats. Stay to the right and turn the When you paddle, please observe these principles of Leave bow into their wake. Respect anglers. Paddle to the No Trace. For more information, log on to Leave No Trace shore opposite their lines. at www.lnt.org. 6. Respect wildlife. Do not approach or harass wildlife, as they can be dangerous. It’s illegal to feed them. q Plan Ahead and Prepare q Camp on Durable Surfaces 7. Bring a cell phone in case of an emergency. Cell q Dispose of Waste Properly phone coverage can be sporadic, so careful preparation q Leave What You Find and contingency plans should be made in lieu of relying on q Minimize Campfire Impacts cell phone reception. q Respect Wildlife FloridaPaddling Trails q Be Considerate of Other Visitors 8. If you are paddling on your own, give a reliable A Guide to Florida’s Top person your float plan before you leave and www.FloridaGreenwaysAndTrails.com leave a copy on the dash of your car. A float Canoeing & Kayaking Trails Trail Tips plan contains information about your trip in the event that When you paddle, please follow these tips. Water you do not return as scheduled. Don’t forget to contact the conditions vary and it will be up to you to be person you left the float plan with when you return. You can prepared for them. download a sample float plan at http://www.floridastateparks.org/wilderness/docs/FloatPlan.pdf. -

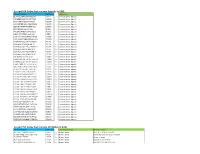

Ascend PSA Codes That Are Now Appeals in GAIL

Ascend PSA Codes that are now Appeals in GAIL Ascend Description: PSA Code: GAIL Location: BLACK ALUMNI ASSN SOLICIT 96688 ---> Communications, Appeals CHAMBER MUS SOLICITATION ASCHA ---> Communications, Appeals RC'D CORINA SOLICITATION ASCOR ---> Communications, Appeals JOY PORTER WILLIAMS FRNDS ASJPW ---> Communications, Appeals SENIOR ADMI/PARTNERS SOL DVSRA ---> Communications, Appeals ENV DESIGN SOLICIT 2006 EVS06 ---> Communications, Appeals FACS PLANNED GIVING SOLIC FC100 ---> Communications, Appeals GMOA DC APPEAL 2000-2001 GMDC1 ---> Communications, Appeals LAW SCH 95 FALL PHONATHON LW95F ---> Communications, Appeals LAW PHONATHON REFUSALS 95 LWRFS ---> Communications, Appeals PHONATHN CLS OF'78 LYBUNT RC742 ---> Communications, Appeals RUFFALO INCOMPLETES '97 RC7NO ---> Communications, Appeals RUFFALO CODY FALL PHONATH RC96A ---> Communications, Appeals RUFFALO CODY LYBUNTS 96 RC96L ---> Communications, Appeals RUFFALO CODY REUNIONS '96 RC96R ---> Communications, Appeals RUFFALO CODY SYBUNTS 96 RC96S ---> Communications, Appeals DATABASE TO RC 8/27/98 RCDB1 ---> Communications, Appeals NONDONOR DB TO RUFFALO CO RCDB2 ---> Communications, Appeals PHONABLE DB TO RUFFALO CO RCDBA ---> Communications, Appeals FAM & CONS SCI TO RUFFALO RCFCS ---> Communications, Appeals JOURNLM GRADS TO RUFFALO RCJRL ---> Communications, Appeals GEN LYBS TO RUFF CODY '00 RCLY0 ---> Communications, Appeals LYBUNTS TO RUFFALO CODY RCLY9 ---> Communications, Appeals RC SOL-AG MAJOR PROSPECT RCMAG ---> Communications, Appeals RC SOL-ARTS&SCI MAJ PROSP