J. Whitfield Gibbons SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of Amphibian Community Monitoring at Canaveral National Seashore, 2009

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Summary of Amphibian Community Monitoring at Canaveral National Seashore, 2009 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2010/098 ON THE COVER Clockwise from top left, Hyla chrysoscelis (Cope’s grey treefrog), Hyla gratiosa (barking treefrog), Scaphiopus holbrookii (Eastern spadefoot), and Hyla cinerea (Green treefrog). Photographs by J.D. Willson. Summary of Amphibian Community Monitoring at Canaveral National Seashore, 2009 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2010/098 Michael W. Byrne, Laura M. Elston, Briana D. Smrekar, Brent A. Blankley, and Piper A. Bazemore USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network Cumberland Island National Seashore 101 Wheeler Street Saint Marys, Georgia, 31558 October 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Checklist of Reptiles and Amphibians Revoct2017

CHECKLIST of AMPHIBIANS and REPTILES of ARCHBOLD BIOLOGICAL STATION, the RESERVE, and BUCK ISLAND RANCH, Highlands County, Florida. Voucher specimens of species recorded from the Station are deposited in the Station reference collections and the herpetology collection of the American Museum of Natural History. Occurrence3 Scientific name1 Common name Status2 Exotic Station Reserve Ranch AMPHIBIANS Order Anura Family Bufonidae Anaxyrus quercicus Oak Toad X X X Anaxyrus terrestris Southern Toad X X X Rhinella marina Cane Toad ■ X Family Hylidae Acris gryllus dorsalis Florida Cricket Frog X X X Hyla cinerea Green Treefrog X X X Hyla femoralis Pine Woods Treefrog X X X Hyla gratiosa Barking Treefrog X X X Hyla squirella Squirrel Treefrog X X X Osteopilus septentrionalis Cuban Treefrog ■ X X Pseudacris nigrita Southern Chorus Frog X X Pseudacris ocularis Little Grass Frog X X X Family Leptodactylidae Eleutherodactylus planirostris Greenhouse Frog ■ X X X Family Microhylidae Gastrophryne carolinensis Eastern Narrow-mouthed Toad X X X Family Ranidae Lithobates capito Gopher Frog X X X Lithobates catesbeianus American Bullfrog ? 4 X X Lithobates grylio Pig Frog X X X Lithobates sphenocephalus sphenocephalus Florida Leopard Frog X X X Order Caudata Family Amphiumidae Amphiuma means Two-toed Amphiuma X X X Family Plethodontidae Eurycea quadridigitata Dwarf Salamander X Family Salamandridae Notophthalmus viridescens piaropicola Peninsula Newt X X Family Sirenidae Pseudobranchus axanthus axanthus Narrow-striped Dwarf Siren X Pseudobranchus striatus -

Athens Campus

Athens Campus Athens Campus Introduction The University of Georgia is centered around the town of Athens, located approximately 60 miles northeast of the capital of Atlanta, Georgia. The University was incorporated by an act of the General Assembly on January 25, 1785, as the first state-chartered and supported college in the United States. The campus began to take physical form after a 633-acre parcel of land was donated for this purpose in 1801. The university’s first building—Franklin College, now Old College—was completed in 1806. Initially a liberal-arts focused college, University of Georgia remained modest in size and grew slowly during the Figure 48. Emblem of the antebellum years of the nineteenth century. In 1862, passage of the Morrill Act University of Georgia. by Congress would eventually lead to dramatic changes in the focus, curriculum, and educational opportunities afforded at the University of Georgia. The Morrill Act authorized the establishment of a system of land grant colleges, which supported, among other initiatives, agricultural education within the United States. The University of Georgia began to receive federal funds as a land grant college in 1872 and to offer instruction in agriculture and mechanical arts. The role of agricultural education and research has continued to grow ever since, and is now supported by experiment stations, 4-H centers, and marine institutes located throughout the state. The Athens campus forms the heart of the University of Georgia’s educational program. The university is composed of seventeen colleges and schools, some of which include auxiliary divisions that offer teaching, research, and service activities. -

Post-Secondary Nominee Presentation Form U.S. Department of Education Green Ribbon Schools Postsecondary 2015-2018

Post-Secondary Nominee Presentation Form ELIGIBILITY CERTIFICATIONS College or University Certifications The signature of college or university President (or equivalent) on the next page certifies that each of the statements below concerning the institution’s eligibility and compliance with the following requirements is true and correct to the best of their knowledge. 1. The college or university has been evaluated and selected from among institutions within the Nominating Authority’s jurisdiction, based on high achievement in the three ED-GRS Pillars: 1) reduced environmental impact and costs; 2) improved health and wellness; and 3) effective environmental and sustainability education. 2. The college or university is providing the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights (OCR) access to information necessary to investigate a civil rights complaint or to conduct a compliance review. 3. OCR has not issued a violation letter of findings to the college or university concluding that the nominated college or university has violated one or more of the civil rights statutes. A violation letter of findings will not be considered outstanding if OCR has accepted a corrective action plan to remedy the violation. 4. The U.S. Department of Justice does not have a pending suit alleging that the college or university has violated one or more of the civil rights statutes or the Constitution’s equal protection clause. 5. There are no findings by Federal Student Aid of violations in respect to the administration of Title IV student aid funds. 6. The college or university is in good standing with its regional or national accreditor. -

Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge Amphibians, Fish, Mammals and Reptiles List

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge Amphibians, Fish, Mammals and Reptiles List The Okefenokee swamp is covered with Mammals ___Seminole Bat cypress, blackgum, and bay forests (Lasiurus seminolus). A common bat of scattered throughout a flooded prairie ___Virginia Opossum the Okefenokee which is found hanging in made of grasses, sedges, and various (Didelphis virginiana pigna). Common on Spanish Moss during the day. the swamp edge and the islands within aquatic plants. The peripheral upland and ___Hoary Bat the almost 70 islands within the swamp the Swamp. A night prowler. “Pogo” is often seen by campers. (Lasiurus cinereus cinereus). This are forested with pine interspersed with yellowish-brown bat flies high in the air hardwood hammocks. Lakes of varying ___Southern Short-Tailed Shrew late at night and will hang in trees when sizes and depths, and floating sections (Barina carolinensis). A specimen was resting. It is the largest bat in the East of the peat bed, are also part of the found on Floyds Island June 12, 1921. It and eats mostly moths. Okefenokee terrain. kills its prey with poisonous saliva. ___Northern Yellow Bat People have left their mark on the swamp. ___Least Shrew (Lasiurus intermedius floridanus). A 12-mile long canal was dug into the (Cryptotus parva parva). Rarely seen but Apparently a rare species in the area. It eastern prairies in the 1890’s in a failed probably fairly common. Specimens have likes to feed in groups. attempt to drain the swamp. During the been found on several of the islands, on early 1900’s large amounts of timber were the swamp edge, and in the pine woods ___Evening Bat removed, so that very few areas of virgin around the swamp. -

University of Georgia Historical Background

University of Georgia Historical Background A Brief History of the University of Georgia Et docere et rerum exquirere causas. To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things. – University of Georgia motto Figure 2. Campus Map, 1899. (Source: University of Georgia) The history of the University of Georgia (UGA) generally parallels that of the State of Georgia itself. Georgia became the fourth state of the United States after voting to ratify the Constitution on January 2, 1788. Statehood closely followed the Georgia General Assembly’s establishment of UGA in 1785, the first chartered state university in the nation. After approval of the charter, the legislature appointed governing boards and a president, Abraham Baldwin. It would take sixteen years to navigate the challenges associated with securing support, funding, and a location for the new school before students could be admitted in 1801.9 For much of its history, UGA has supported the evolving 9. F. N. Boney, A Pictorial History of The University of Georgia, second edition (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1984), 2–3. University of Georgia Historic Preservation Master Plan 9 University of Georgia Historical Background educational and vocational training needs of the citizenry of the state of Georgia, over time becoming closely tied to innovation in agriculture and scientific research. The information provided below offers a brief overview of UGA’s history, encompassing development of the Athens campus as well as the various other historic properties that support University programs and activities. It is followed by the identification of historic contexts within which the University’s historic properties may be better understood. -

AG-472-02 Snakes

Snakes Contents Intro ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................1 What are Snakes? ...............................................................1 Biology of Snakes ...............................................................1 Why are Snakes Important? ............................................1 People and Snakes ............................................................3 Where are Snakes? ............................................................1 Managing Snakes ...............................................................3 Family Colubridae ...............................................................................................................................................................................................5 Eastern Worm Snake—Harmless .................................5 Red-Bellied Water Snake—Harmless ....................... 11 Scarlet Snake—Harmless ................................................5 Banded Water Snake—Harmless ............................... 11 Black Racer—Harmless ....................................................5 Northern Water Snake—Harmless ............................12 Ring-Necked Snake—Harmless ....................................6 Brown Water Snake—Harmless .................................12 Mud Snake—Harmless ....................................................6 Rough Green Snake—Harmless .................................12 -

Biodiversity and Coarse Woody Debris in Southern Forests Proceedings of the Workshop on Coarse Woody Debris in Southern Forests: Effects on Biodiversity

Biodiversity and Coarse woody Debris in Southern Forests Proceedings of the Workshop on Coarse Woody Debris in Southern Forests: Effects on Biodiversity Athens, GA - October 18-20,1993 Biodiversity and Coarse Woody Debris in Southern Forests Proceedings of the Workhop on Coarse Woody Debris in Southern Forests: Effects on Biodiversity Athens, GA October 18-20,1993 Editors: James W. McMinn, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Athens, GA, and D.A. Crossley, Jr., University of Georgia, Athens, GA Sponsored by: U.S. Department of Energy, Savannah River Site, and the USDA Forest Service, Savannah River Forest Station, Biodiversity Program, Aiken, SC Conducted by: USDA Forest Service, Southem Research Station, Asheville, NC, and University of Georgia, Institute of Ecology, Athens, GA Preface James W. McMinn and D. A. Crossley, Jr. Conservation of biodiversity is emerging as a major goal in The effects of CWD on biodiversity depend upon the management of forest ecosystems. The implied harvesting variables, distribution, and dynamics. This objective is the conservation of a full complement of native proceedings addresses the current state of knowledge about species and communities within the forest ecosystem. the influences of CWD on the biodiversity of various Effective implementation of conservation measures will groups of biota. Research priorities are identified for future require a broader knowledge of the dimensions of studies that should provide a basis for the conservation of biodiversity, the contributions of various ecosystem biodiversity when interacting with appropriate management components to those dimensions, and the impact of techniques. management practices. We thank John Blake, USDA Forest Service, Savannah In a workshop held in Athens, GA, October 18-20, 1993, River Forest Station, for encouragement and support we focused on an ecosystem component, coarse woody throughout the workshop process. -

2017 National Veterinary Scholars Symposium 18Th Annual August 4

2017 National Veterinary Scholars Symposium 18th Annual August – 4 5, 2017 Natcher Conference Center, Building 45 National Institutes of Health Bethesda, Maryland Center for Cancer Research National Cancer Institute with The Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges https://www.cancer.gov/ Table of Contents 2017 National Veterinary Scholars Symposium Program Booklet Welcome .............................................................................................................................. 1 NIH Bethesda Campus Visitor Information and Maps .........................................................2 History of the National Institutes of Health ......................................................................... 4 Sponsors ............................................................................................................................... 5 Symposium Agenda .......................................................................................................6 Bios of Speakers ................................................................................................................. 12 Bios of Award Presenters and Recipients ........................................................................... 27 Training Opportunities at the NIH ...................................................................................... 34 Abstracts Listed Alphabetically .......................................................................................... 41 Symposium Participants by College of Veterinary Medicine -

Venomous Nonvenomous Snakes of Florida

Venomous and nonvenomous Snakes of Florida PHOTOGRAPHS BY KEVIN ENGE Top to bottom: Black swamp snake; Eastern garter snake; Eastern mud snake; Eastern kingsnake Florida is home to more snakes than any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. Since only six species are venomous, and two of those reside only in the northern part of the state, any snake you encounter will most likely be nonvenomous. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission MyFWC.com Florida has an abundance of wildlife, Snakes flick their forked tongues to “taste” their surroundings. The tongue of this yellow rat snake including a wide variety of reptiles. takes particles from the air into the Jacobson’s This state has more snakes than organs in the roof of its mouth for identification. any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. They are found in every Fhabitat from coastal mangroves and salt marshes to freshwater wetlands and dry uplands. Some species even thrive in residential areas. Anyone in Florida might see a snake wherever they live or travel. Many people are frightened of or repulsed by snakes because of super- stition or folklore. In reality, snakes play an interesting and vital role K in Florida’s complex ecology. Many ENNETH L. species help reduce the populations of rodents and other pests. K Since only six of Florida’s resident RYSKO snake species are venomous and two of them reside only in the northern and reflective and are frequently iri- part of the state, any snake you en- descent. -

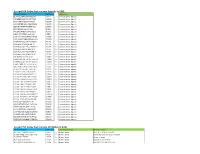

Ascend PSA Codes That Are Now Appeals in GAIL

Ascend PSA Codes that are now Appeals in GAIL Ascend Description: PSA Code: GAIL Location: BLACK ALUMNI ASSN SOLICIT 96688 ---> Communications, Appeals CHAMBER MUS SOLICITATION ASCHA ---> Communications, Appeals RC'D CORINA SOLICITATION ASCOR ---> Communications, Appeals JOY PORTER WILLIAMS FRNDS ASJPW ---> Communications, Appeals SENIOR ADMI/PARTNERS SOL DVSRA ---> Communications, Appeals ENV DESIGN SOLICIT 2006 EVS06 ---> Communications, Appeals FACS PLANNED GIVING SOLIC FC100 ---> Communications, Appeals GMOA DC APPEAL 2000-2001 GMDC1 ---> Communications, Appeals LAW SCH 95 FALL PHONATHON LW95F ---> Communications, Appeals LAW PHONATHON REFUSALS 95 LWRFS ---> Communications, Appeals PHONATHN CLS OF'78 LYBUNT RC742 ---> Communications, Appeals RUFFALO INCOMPLETES '97 RC7NO ---> Communications, Appeals RUFFALO CODY FALL PHONATH RC96A ---> Communications, Appeals RUFFALO CODY LYBUNTS 96 RC96L ---> Communications, Appeals RUFFALO CODY REUNIONS '96 RC96R ---> Communications, Appeals RUFFALO CODY SYBUNTS 96 RC96S ---> Communications, Appeals DATABASE TO RC 8/27/98 RCDB1 ---> Communications, Appeals NONDONOR DB TO RUFFALO CO RCDB2 ---> Communications, Appeals PHONABLE DB TO RUFFALO CO RCDBA ---> Communications, Appeals FAM & CONS SCI TO RUFFALO RCFCS ---> Communications, Appeals JOURNLM GRADS TO RUFFALO RCJRL ---> Communications, Appeals GEN LYBS TO RUFF CODY '00 RCLY0 ---> Communications, Appeals LYBUNTS TO RUFFALO CODY RCLY9 ---> Communications, Appeals RC SOL-AG MAJOR PROSPECT RCMAG ---> Communications, Appeals RC SOL-ARTS&SCI MAJ PROSP -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Hickory Nut Gorge Green Salamander (Aneides caryaensis) Photo by Austin Patton 2014 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. The list is published periodically, generally every two years.