108 Michael G. Flaherty. the Textures of Time: Agency and Temporal Experi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

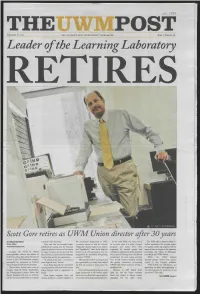

Leader of the Learning Laboratory RETIRES

THE POSTest-, lyob September 6, 2011 THE STUDENT-RUN INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER Issue 2, Volume $6 Leader of the Learning Laboratory RETIRES Scott Gore retires as UWM Union director after 30years By Steve Garrison assistant to the chancellor. the reservations department in 1972, In the early 1970s, the union was a The UAB, still in existence today, is a News Editor Gore said that the biennial budget a position referred to him by a friend. far cry from what it is today. Campus student organization that provides support [email protected] published last spring and the financial Originally a theater major, Gore said he programs and events were often for speakers, events and programs with the impact it may have was part of the reason had "highfalutin" ideas about what he organized by external groups and intent to have an impact on the university, Campus life would be almost he chose to leave, but he also felt that wanted to do after graduation, but was individuals independent of the university community and culture of Milwaukee, unrecognizable without the efforts of after 30 years, it maybe time for a change, intrigued by the possibility of beginning who received funding from the federal according to the UWM website. Scott Gore, who, after almost 30 years of both for him and for the organization. a career at UWM. government. As such, union activities While the UAB allowed service to the UW-Milwaukee campus, "It is kind of my time ... to retool in "My experiences here on campus and were mostly business-minded, serving students greater control over campus announced his retirement as Student some shape or form," he said. -

Tha Carter V Free Download Tha Carter V Free Download

tha carter v free download Tha carter v free download. DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Lil Wayne. Weezy not long ago shared the news of him being the sole owner of Young Money after reaching an agreement with Birdman and Cash Money who was partial owner of the label he founded, and we hope the deal lasts. Rap Artist Lil Wayne has actually finally exposed the release date for his long-awaited album The Cater V. The project has for many years witnessed so much undesirable delays coming from legal disputes between Lil Wayne and his former label boss, Birdman of Cash Money Records. Album: Lil Wayne — Tha Carter V 2018 Free Album Zip Download: The new album, Tha Carter V from American singer and song writer Lil Wayne is his newest and twelfth studio album the the one time best rapper. Album: Lil Wayne — Tha Carter V 2018 Free Album Zip Download: The new album, Tha Carter V from American singer and song writer Lil Wayne is his newest and twelfth studio album the the one time best rapper. There is no description regarding how this reduction in payment associates to Wayne's original claim that Cash Money chose not to release his album. Then, Cash Money became the issue as Birdman was consistently stopping the release of the much-anticipated album. Download Tha Carter V (2018) album zip, rar, by Lil Wayne Mp3 Download. Birdman had to sense disloyalty in the air and Tha Carter V is a small casualty of this blatant disrespect. Now with Lil Wayne jumping on twitter yet again to declare his intentions to quit the game, Birdman again gets the blame. -

Defining and Transgressing Norms of Black Female Sexuality

Wesleyan University The Honors College (Re)Defining and Transgressing Norms of Black Female Sexuality by Indee S. Mitchell Class of 2010 A thesis (or essay) submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Dance Middletown, Connecticut April 13, 2010 1 I have come to believe over and over again that what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared, even at the risk of having it bruised or misunderstood -Audre Lorde 2 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my most sincere and heart filled appreciation to the faculty and staff of both the Dance and Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Departments, especially my academic and thesis advisor, Katja, who has supported and guided me in ways I never could expect. Thank you Katja for believing in me, my art, and the power embedded within. Both the Dance and FGSS departments have contributed to me finding and securing my artistic and academic voice as a Queer GenderFucking Womyn of Color; a voice that I will continue to use for the sake of art, liberation and equality. I would also like to thank the coordinators of the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship, Krishna and Rene, for providing me with tools and support throughout this process of creation, as well as my fellow Mellon fellows for their most sincere encouragement (We did it Guys!). I cannot thank my dancers and artistic collaborators (Maya, Simone, Randyll, Jessica, Temnete, Amani, Adeneiki, Nicole and Genevive) enough for their contributions and openness to this project. -

Pdf 1-8., Accessed March 2014

THE BIOCULTURAL IMPACT OF ETHNIC HEALTH AND BEAUTY PRODUCT CONSUMPTION AMONG SOUTH FLORIDA JAMAICAN WOMEN By BRITTANY MONIQUE OSBOURNE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2015 © 2015 Brittany Monique Osbourne To my ancestors and parents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The following dissertation evolved over the course of five years with the help of many people. I would first like to pay honor and respect to my spiritual compass, my creator, whose love and wisdom guided me along this doctoral path. To my ancestors, both ancient and recently transitioned, I pay homage. No amount of verbal libations can ever truly honor the sacrifices they endured, so the living would not have to know their struggles. In particular, I would like to honor those ancestors who survived the Maafa. Without them, I would not be. I would also like to honor my Jamaican ancestors, particularly my Windward Maroon ancestors of Portland Parish. The legacy of their warrior spirits kept me strong throughout this process, and motivated me to continue the good fight of completing this work. I thank my intellectual ancestress Zora Neale Hurston, who I am very proud to have been directly trained by those who were trained by those who trained her. Her ethnographic and literary works spoke to me, and were always a constant reminder that those of us who are a blend of the fine arts and the social sciences are uniquely positioned to be a transformative voice for the voiceless. -

Zine Culture: Identity & Agency Trajectories in an ELA Classroom William K

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Doctor of Education in Secondary Education Department of Secondary and Middle Grades Dissertations Education Spring 3-13-2017 Zine Culture: Identity & Agency Trajectories in an ELA Classroom William K. Jones Kennesaw State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/seceddoc_etd Part of the Secondary Education Commons Recommended Citation Jones, William K., "Zine Culture: Identity & Agency Trajectories in an ELA Classroom" (2017). Doctor of Education in Secondary Education Dissertations. 7. http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/seceddoc_etd/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Secondary and Middle Grades Education at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Education in Secondary Education Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zine Culture: Identity & Agency Trajectories in an ELA Classroom By W. Kyle Jones A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education In Secondary Education English Copyright © W. Kyle Jones 2017 All rights reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My love of writing grew from the moment Ms. B, my readiness teacher, helped me publish my own story of a white cat that visited a magical land after falling into a rainbow. My love of reading began at the age of ten when my dad handed me the book Ender’s Game, and I became immersed in the psychology of a child my age playing the war games of adults. I fortified my love of writing when my friends humored me and read my angsty, teenage poetry and told me they liked it—they were being kind to say the least. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Jimmy Rankin – Back Road Paradise • Enrique

Jimmy Rankin – Back Road Paradise Enrique Iglesias – Sex And Love Avicii – True: Avicii By Avicii New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI14-11 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Stompin’ Tom Connors / Unreleased: Songs From The Vault Collection Volume 1 Cat. #: 0253777712 Price Code: SP Order Due: March 6, 2014 Release Date: April 1, 2014 File: Country Genre Code: 16 Box Lot: 25 Tracks / not final sequence 6 02537 77712 9 Tom and Guitar: 12 songs 10. I'll Sail My Ship Alone 1. Blue Ranger 11. When My Blue Moon Turns to Gold 2. Rattlin' Cannonball 12. I Overlooked an Orchid 3. Turkey in The straw ( Instrumental ) 4. John B. Sails Tom Originals with Band: 5. Truck Drivin' Man 1. Cross Canada, aka C.A.N.A.D.A 6. Wild Side of Life 2. My Stompin' Grounds 7. Pawn Shop in Pittsburgh, aka, Pittsburgh 3. Movin' In From Montreal By Train Pennsylvania 4. Flyin' C.P.R. 8. Nobody's Child 5. Ode for the Road 9. Darktown Strutter's Ball This is the Premier Release in an upcoming series of Unreleased Material by Stompin' Tom Connors! In 2011, Tom decided after what ended up being his final Concert Tour, that he would record another 10 album set with a lot of old songs that he sang when he first started out performing in the 50's and 60's.This was back when he could sing, from memory, over 2500 songs in his repertoire and long before he wrote many of his own hits we all know today. -

Young Money 2010 Mixtape

Young money 2010 mixtape Released: March 23, We Are Young Money is the first compilation album by American hip hop record label Young Young Money: The Mixtape Vol. 1'Released: December 21, Young Money, Lil Wayne - Young Money The Mixtape Vol 1 (Disc 1) - Free Mixtape Download or Stream it. St Laz, Young Money, P Swagger, Lloyd Banks, Juelz Santana, City Boy, Lil Flip, Chamillionaire, Bonafide, Motion, Jo Blak, Vain, Jim jones, Maino, Five, J Stills. Young Money discography and songs: Music profile for Young Money, formed Genres: Pop Rap, Southern Hip Hop. • Mixtape • Lil Wayne. 5. Young Money Lil wayne Drake Mixtape - Man of the Year - Cop the New Era Fitteds at http. Lil Wayne Sacrifice ft Drake Young Money Mixtape - Cop this fitted at. Lil Wayne Young Money Wayne S World 7 Mixtape Mixtape Mp3 Download Lil Lil Wayne Sacrifice Ft Drake Young Money Mixtape Mp3 Download Lil. Mack Maine caught up with Revolt TV to talk about some upcoming projects you can expect from Young Money in He confirmed that there will be albums. Here is the Young Money “We Are Young Money” album tracklisting Young Money Album Gets Official Title & Comes With A DVD bull i wanted like at least 25 wayne put more songs on his mixtapes January 1, Young Money Entertainment dropped a free mixtape, Young Money The Mixtape Volume 1, in to make their sound known to the streets of hip- hop. Young Money Entertainment is an American record label founded by rapper Lil Wayne. Young Money's president is Lil Wayne's lifelong friend Mack Maine. -

Kang Sung R.Pdf

ILLUSTRATED AMERICA: FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND THE DEMOCRATIZATION OF TATTOOS IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CULTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 2014 By Sung P. Kang Dissertation Committee: Herbert Ziegler, Chairperson Margot Henriksen Marcus Daniel Njoroge Njoroge Kathryn Hoffmann Keywords: tattoos, skin art, sports, cultural studies, ethnic studies, gender studies ©Copyright 2014 by Sung P. Kang ii Acknowledgements This dissertation would not be possible without the support and assistance of many of the History Department faculty and staff from the University of Hawaii, colleagues from Hawaii Pacific University, friends, and family. I am very thankful to Njoroge Njoroge in supplying constant debates on American sports and issues facing black athletes, and furthering my understanding of Marxism and black America. To Kathryn Hoffmann, who was a continuous “springboard” for many of my theories and issues surrounding the body. I also want to thank Marcus Daniel, who constantly challenged my perspective on the relationship between politics and race. To Herbert Ziegler who was instrumental to the entire doctoral process despite his own ailments. Without him none of this would have been possible. To Margot (Mimi) Henriksen, my chairperson, who despite her own difficulties gave me continual assistance, guidance, and friendship that sustained me to this stage in my academic career. Her confidence in me was integral, as it fed my determination not to disappoint her. To my chiropractor, Dr. Eric Shimane, who made me physically functional so I could continue with the grueling doctoral process. -

22 MOTION for Default Judgment As to Defendant. Filed by Bigface

b.I.G.f.a.c.e. Entertainment, Inc. v. Young Money Entertainment, LLC Doc. 36 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK -------------------------------------------------------x b.I.G.f.a.c.e. ENTERTAINMENT, INC. f/s/o LAVELL CRUMP p/k/a DAVID BANNER, Plaintiff, -v- No. 15 CV 5878-LTS YOUNG MONEY ENTERTAINMENT, LLC, Defendant. -------------------------------------------------------x MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER On July 27, 2015, Plaintiff b.I.G.f.a.c.e. Entertainment, Inc., f/s/o Lavell Crump p/k/a David Banner (“Plaintiff”) filed this action against Young Money Entertainment, LLC (“Defendant”), seeking damages for breach of two agreements the parties executed in 2008 and 2009 (the “2008 Agreement” and “2009 Agreement,” respectively). Plaintiff alleges in its Complaint (docket entry no. 1 (“Compl.”)) that it satisfactorily performed all of its obligations to Defendant under both agreements, but that Defendant failed to uphold its end of the bargains. The Court has jurisdiction of this action pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1332(a)(1). Plaintiff has moved for judgment by default pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 55. (See docket entry no. 22.) The Clerk of this Court certified Defendant’s default on February 2, 2016. (Docket entry no. 19.) The Court has carefully considered all of Plaintiff’s submissions and, for the reasons set forth below, the grants Plaintiff’s motion and enters judgment by default against Defendant in the amount of $164,303.19, plus pre-judgment interest at 9% per annum. BIGFACE V. YOUNG MONEY - DEFAULT J.WPD VERSION SEPTEMBER 19, 2016 1 Dockets.Justia.com BACKGROUND This case arises from two Producer Agreements between the parties. -

Bad Bitches, Jezebels, Hoes, Beasts, and Monsters

BAD BITCHES, JEZEBELS, HOES, BEASTS, AND MONSTERS: THE CREATIVE AND MUSICAL AGENCY OF NICKI MINAJ by ANNA YEAGLE Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Thesis Adviser: Dr. Francesca Brittan, Ph.D. Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August, 2013 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis of ____ ______ _____ ____Anna Yeagle_____________ ______ candidate for the __ __Master of Arts__ ___ degree.* __________Francesca Brittan__________ Committee Chair __________Susan McClary__________ Committee Member __________Daniel Goldmark__________ Committee Member (date)_____June 17, 2013_____ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures i Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii INTRODUCTION: “Bitch Bad, Woman Good, Lady Better”: The Semiotics of Power & Gender in Rap 1 CHAPTER 1: “You a Stupid Hoe”: The Problematic History of the Bad Bitch 20 Exploiting Jezebel 23 Nicki Minaj and Signifying 32 The Power of Images 42 CHAPTER 2: “I Just Want to Be Me and Do Me”: Deconstruction and Performance of Selfhood 45 Ambiguous Selfhood 47 Racial Ambiguity 50 Sexual Ambiguity 53 Gender Ambiguity 59 Performing Performativity 61 CHAPTER 3: “You Have to be a Beast”: Using Musical Agency to Navigate Industry Inequities 67 Industry Barriers 68 Breaking Barriers 73 Rap Credibility and Commercial Viability 75 Minaj the Monster 77 CONCLUSION: “You Can be the King, but Watch the Queen -

Előadó Album Címe a Balladeer Panama -Jewelcase- a Balladeer Where Are You, Bambi

Előadó Album címe A Balladeer Panama -Jewelcase- A Balladeer Where Are You, Bambi.. A Fine Frenzy Bomb In a Birdcage A Flock of Seagulls Best of -12tr- A Flock of Seagulls Playlist-Very Best of A Silent Express Now! A Tribe Called Quest Collections A Tribe Called Quest Love Movement A Tribe Called Quest Low End Theory A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Trav Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothin' But a N Ab/Cd Cut the Crap! Ab/Cd Rock'n'roll Devil Abba Arrival + 2 Abba Classic:Masters.. Abba Icon Abba Name of the Game Abba Waterloo + 3 Abba.=Tribute= Greatest Hits Go Classic Abba-Esque Die Grosse Abba-Party Abc Classic:Masters.. Abc How To Be a Zillionaire+8 Abc Look of Love -Very Best Abyssinians Arise Accept Balls To the Wall + 2 Accept Eat the Heat =Remastered= Accept Metal Heart + 2 Accept Russian Roulette =Remaste Accept Staying a Life -19tr- Acda & De Munnik Acda & De Munnik Acda & De Munnik Adem-Het Beste Van Acda & De Munnik Live Met Het Metropole or Acda & De Munnik Naar Huis Acda & De Munnik Nachtmuziek Ace of Base Collection Ace of Base Singles of the 90's Adam & the Ants Dirk Wears White Sox =Rem Adam F Kaos -14tr- Adams, Johnny Great Johnny Adams Jazz.. Adams, Oleta Circle of One Adams, Ryan Cardinology Adams, Ryan Demolition -13tr- Adams, Ryan Easy Tiger Adams, Ryan Love is Hell Adams, Ryan Rock'n Roll Adderley & Jackson Things Are Getting Better Adderley, Cannonball Cannonball's Bossa Nova Adderley, Cannonball Inside Straight Adderley, Cannonball Know What I Mean Adderley, Cannonball Mercy -

Im on It Tyga

Im on it tyga click here to download [Tyga] I'm on it, I'm on it. I'm on it, I'm on it. If we talkin' bout money bitch [Tyga - Verse 1] Snap back chiller gold chain nigga snaps no tigger, tyga bitches. I'm On One Lyrics: All these niggas stealing swag / I've been getting tats since I was fourteen / Tell my bitch throw it in the bag / Twenty-two for the Balmain jeans . View the Lil Wayne lyrics for the song I'm On It with Tyga. Discover releases, reviews, credits, songs, and more about Tyga Feat. Lil Wayne - I'm On It at Discogs. Complete your Tyga Feat. Lil Wayne collection. Find a Tyga Feat. Lil Wayne - I'm On It first pressing or reissue. Complete your Tyga Feat. Lil Wayne collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Listen to I'm On It (NO DJ), the new track by Tyga featuring Lil' Wayne which was dropped on Sunday, February 28th, Listen to I'm On It (NO DJ), the la. I'm On It. By Tyga, Lil Wayne. • 1 song, Play on Spotify. 1. I'm On It - Lil Wayne. Featured on I'm On It. We've been waiting on this one since the night before Wayne was scheduled to go to prison and gave a sneak peek when he took Lil Twist and. With a rangy set of friends from Fall Out Boy to Lil Wayne, it was obvious from the start that Tyga was not your everyday rapper from Compton. After recording a.