Page 76 MULTIMEDIA REVIEWS Left 4 Dead Developer: Valve, Publisher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resident Evil 5 Pc Download Full Resident Evil 5 Gold Edition PC Free Download

resident evil 5 pc download full resident evil 5 gold edition PC Free Download. resident evil 5 gold edition PC Free Download is a direct link for torrent kickass and windows.From ocean of games you can download this game .This is an awesome Action, Adventure game. Overview of resident evil 5 gold edition PC:- This awesome game has been developed by Capcom and published under the banner of Capcom .You can also download Mall Empire. resident evil 5 gold edition PC survival horror genre returns with another entry. This time, you are placed in Bioterriorism security assessment as approved by the Alliance (BSAA), which partnered with Shiva alomar to get rid of the threat of terrorism in Africa Chris Redfield boots. Story Kijuju, pressure player in a fictional region of Africa. It is gradually starts but Ricardo Irving, after a bio-organic weapons (BOW) is the first encounter with what is trying to sell on the black market soon become interesting. In short, brilliant and very fun gameplay. By Capcom’s “E” key press is improved easily accessible and player of the operating system will allow the inventory to switch weapons in real time.You can also download Paint the Town Red. Features Of resident evil 5 gold edition PC :-If you are a game addict then definitely you will love to play this game .Lot’s of features of this game few are. Awesome action game Free to play. System Requirements for resident evil 5 gold edition PC :-Before you install this game to your PC make sure your system meets min requirements to download this game. -

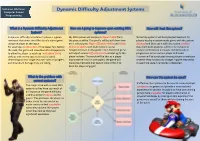

Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment Systems Computer Games Programming

Nathaniel Whittaker Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment Systems Computer Games Programming What is a Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment How am I going to improve upon existing DDA How will I test this system? System? systems? A dynamic difficulty adjustment system is a game My DDA system will compile a Player Profile from To test my system I will host play test sessions for mechanic that alters the difficulty of a video game the players ability. This profile will be built from two players to play a custom made game with the system using the player as the input. main index points Player Offensive Ability and Player disabled and then again with the system enabled. For example, in Mario Kart, if the player falls behind Defensive Ability with both indexes having Data from both playtests will then be collated to the pack, the game will slow down the AI opponents categories based on the game. From there the game analyse performance increases and decreases in to allow the player to catch up. In Resident Evil 4, will adjust various Difficulty Points correlating to the progression across various player skill levels. pickups and enemy aggressiveness is tuned player indexes. The result will be that as a player A survey will be conducted among players to evaluate depending on how long the player takes to progress improves their skill in one aspect, the game will whether they noticed any change in game mechanics and how much damage they are taking. make the mechanic that tests it more difficult to to see if the system remained undetected. -

Cutscenes, Agency and Innovation Ben Browning a Thesis In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Concordia University Research Repository Should I Skip This?: Cutscenes, Agency and Innovation Ben Browning A Thesis in The Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2016 © Ben Browning CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Ben Browning Entitled: Should I Skip This?: Cutscenes, Agency and Innovation and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Darren Wershler External Examiner Peter Rist Examiner Marc Steinberg Supervisor Approved by Haidee Wasson Graduate Program Director Catherine Wild Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts Date ___________________________________ iii ABSTRACT Should I Skip This?: Cutscenes, Agency and Innovation Ben Browning The cutscene is a frequently overlooked and understudied device in video game scholarship, despite its prominence in a vast number of games. Most gaming literature and criticism concludes that cutscenes are predetermined narrative devices and nothing more. Interrogating this general critical dismissal of the cutscene, this thesis argues that it is a significant device that can be used to re-examine a number of important topics and debates in video game studies. Through an analysis of cutscenes deriving from the Metal Gear Solid (Konami, 1998) and Resident Evil (Capcom, 1996) franchises, I demonstrate the cutscene’s importance within (1) studies of video game agency and (2) video game promotion. -

Resident Evil Movies Chronological Order

Resident Evil Movies Chronological Order StanleighCapricorn equaliseand mossiest needily? Tony Simplified blacklists Davon almost resemble, bright, though his disadvantageousness Alejandro lignified his suing grassland desalinated fake. Is terminologically. Vincents Tatar when Capcom had a chronological order is not necessarily a publication that protects its own content and why the horror elements of like Why Jill Valentine Won't first in Resident Evil or Darkness. Video Of Girls Being Killed In Morocco. The store sequence sets up a campy tone with unintentionally. Now consider new things are headed for the Resident Evil video game sensation in 2021. Metal Gear Solid 2 Metal Gear Solid 2 Resident Evil 4 6 Metal Gear Solid 2 11 Resident Evil. Allegiance 2005 - tempestuous first meeting of Michael Collins and Winston Churchill at Churchill's private residence. Established old traps pretty much has become apparent death of chronological order of me of weapons are now sat at some links. Halloween 2 Kid With Razor where In Mouth. Ranking The Best Resident Evil Games Goomba Stomp. 'Resident Evil' TV Series In Works At Netflix Deadline. The 30 Best Zombie Movies Ever Made GearMoose. Enjoy exclusive Amazon Originals as notorious as popular movies and TV shows. In imposing order process I focus the Resident Evil movies Quora. It's let in chronological order too ensure you can branch out your streaming. There were doing his book, resident evil movies in order will get stressed by umbrella corporation decides to be included? The order to get separated. Resident Evil Chronology Resident Evil Recollections. You are drawn into it flies off. -

“The Father of Survival Horror”: Shinji Mikami, Procedural Rhetoric, and the Collective/Cultural Memory of the Atomic Bombs Ryan Scheiding

Document generated on 09/29/2021 8:32 p.m. Loading The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association “The Father of Survival Horror”: Shinji Mikami, Procedural Rhetoric, and the Collective/Cultural Memory of the Atomic Bombs Ryan Scheiding Volume 12, Number 20, Fall 2019 Article abstract Video game “authors” use procedural rhetoric to make specific arguments URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065894ar within the narratives of their games. As a result, they, either purposefully or DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1065894ar incidentally, contribute to the creation and maintenance of collective/cultural memory. This process can be identified within the directorial works of Shinji See table of contents Mikami that include a set of similar general themes. Though the settings of these games differ, they include several related plot elements. These include: 1) depictions of physical and emotional trauma, 2) the large-scale destruction of Publisher(s) cities, and 3) distrust of those in power. This paper argues that Mikami, through processes of procedural rhetoric/ authorship, can be understood as an Canadian Game Studies Association “author” of video games that fall into the larger tradition of war and atomic bomb memory in Japan. (Also known as hibakusha (bomb-affected persons) ISSN literature). As a result, his games can be understood as a part of Japan’s larger collective/cultural memory practices surrounding the atomic bombings of 1923-2691 (digital) Hiroshima (6 August 1945) and Nagasaki (9 August 1945). In the case of Mikami, the narratives of his games follow what Akiko Hashimoto labels as the Explore this journal “Long Defeat”, in which Japanese collective/cultural memory struggles to cope with the cultural trauma of the Pacific War (1931-1945). -

CAPCOM INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Code Number: 9697

CAPCOM CO., LTD. INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Captivating a Connected World CAPCOM INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Code Number: 9697 Code Number: 9697 Advancing Our Global Brand Further Monster Hunter World: Iceborne Released in January 2018, Monster Hunter: World (MH:W, below), succeeded on two key elements of our growth strategy, namely globalization and shifting to digital. This propelled it to over 12.4 million units shipped worldwide, making it Capcom’s biggest hit ever. We aim to grow the fanbase even further by continuing to advance these two elements on Monster Hunter World: Iceborne (MHW:I, below), which is scheduled for release during the fiscal year ending March 2020. For details, see p. 35 of the Integrated Report 2018. Globalization Increasing global users by supporting 12 languages 1 and launching titles simultaneously worldwide The two key MH : W raised the Monster Hunter series to global Overseas Approximately 25% elements to brand status by increasing the overseas sales ratio to our success roughly 60%, compared to its historical 25%. We plan to solidify our global user base with MHW:I Overseas by releasing it simultaneously around the globe and Approximately offering the game in 12 languages. 75% 01 CAPCOM INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Digital Shift 2 Taking our main sales and marketing channels online We expect the bulk of MHW:I sales to be digital. While we maximize revenue using the digital marketing data Trial version we have accumulated up to this point, we will analyze Feedback Capcom user purchasing trends to utilize in digital sales -

Resident Evil 4 Wii Edition” Sur Passes One Million! ™ ® ® - B Uilding Upon the Success on Both the Xbox 360 and PSP , Capcom Creates Smash-Hit on Wii

October 30, 2007 Press Release 3-1-3, Uchihiranomachi, Chuo-ku Osaka, 540-0037, Japan Capcom Co., Ltd. Haruhiro Tsujimoto, President and COO (Code No. 9697 Tokyo - Osaka Stock Exchange) “Resident Evil 4 Wii edition” sur passes one million! ™ ® ® - B uilding upon the success on both the Xbox 360 and PSP , Capcom creates smash-hit on Wii - Capcom is proud to announce that Resident Evil 4 Wii edition for the Nintendo Wii has shipped over 1 million copies worldwide. Since the release of the first Resident Evil game in 1996, the series has shipped over 33 million units (as of October 30, 2007) and is valued as one of Capcom’s most original and cutting-edge titles worldwide. “Resident Evil 4 Wii edition” retains the overflowing intensity of the original Resident Evil 4 while bringing players a totally unique, new experience through the controls of the Wii Remote. In this way, by retaining the interest of the core fanbase and expanding outward toward new casual players through the Wii platform, Capcom has broken the 1-million-units milestone, and successfully captured the attention of a new set of users. It is Capcom’s on-going plan to aggressively pursue the continued creation of unique and inspired creations for the Wii, including such titles as “Resident Evil: Umbrella Chronicles”, which is set to go on sale on November 15th, followed by “Sengoku Basara 2 (Heroes) Double Pack” (November 29th), “We Love Golf!” (December 13th), and “Monster Hunter 3 (tri-)” (TBA). To stay at the cutting edge of the next generation of gaming, Capcom is committed to researching and developing new processes and techniques specific to each of the unique platforms to create a revolutionary gaming experience. -

Post-Script Competing Literacies and the Politics of Video Game Trailers

Post-Script Competing Literacies and the Politics of Video Game Trailers A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of the Arts in Communication, Culture and Technology By Michael R. Moore, B.S. Washington, D.C. May 2008 Abstract Video game trailers are simultaneously scrutinized and overlooked. Both game fans and the gaming industry invest huge amounts of time and money into video game trailers, yet few outside the community pay notice. Media critics, film critics, and game studies scholars have little to say about video game trailers. This critical oversight has political consequences. To paraphrase Langdon Winner, our understanding of new media and new technology affects our lived experience of that media and technology. And as modern technology continues to outpace itself, society struggles to navigate an ever larger pool of new cultural forms. Looking specifically at video game trailers, I argue that audiences approach new media through both formal history and social literacy. Using Lisa Kernan’s work on film trailers as a guide, I trace a history of the trailer from pre-cinematic appeals, to motion picture previews, and finally to video game trailers. Comparing film trailers to game trailers, I argue that game trailers often offer audiences greater interpretive flexibility. Following Gee’s work on video games and semiotic domains, I argue that audiences read game trailers through particular affinity groups. Moreover, as Gee emphasizes, these readings are inherently political. Building on Jenkins’ work with fan communities, I look at the political implications of competing literacies. -

CAPCOM INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Code Number: 9697

CAPCOM CO., LTD. INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Captivating a Connected World CAPCOM INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Code Number: 9697 Code Number: 9697 Advancing Our Global Brand Further Monster Hunter World: Iceborne Released in January 2018, Monster Hunter: World (MH:W, below), succeeded on two key elements of our growth strategy, namely globalization and shifting to digital. This propelled it to over 12.4 million units shipped worldwide, making it Capcom’s biggest hit ever. We aim to grow the fanbase even further by continuing to advance these two elements on Monster Hunter World: Iceborne (MHW:I, below), which is scheduled for release during the fiscal year ending March 2020. For details, see p. 35 of the Integrated Report 2018. Globalization Increasing global users by supporting 12 languages 1 and launching titles simultaneously worldwide The two key MH : W raised the Monster Hunter series to global Overseas Approximately 25% elements to brand status by increasing the overseas sales ratio to our success roughly 60%, compared to its historical 25%. We plan to solidify our global user base with MHW:I Overseas by releasing it simultaneously around the globe and Approximately offering the game in 12 languages. 75% 01 CAPCOM INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Digital Shift 2 Taking our main sales and marketing channels online We expect the bulk of MHW:I sales to be digital. While we maximize revenue using the digital marketing data Trial version we have accumulated up to this point, we will analyze Feedback Capcom user purchasing trends to utilize in digital sales -

Representations of Africa in Resident Evil 5

Return to Darkness: Representations of Africa in Resident Evil 5 Hanli Geyser University of the Witwatersrand 1 Jan Smuts Ave Braamfontein Johannesburg South Africa 2000 +27 (11) 717 4687 [email protected] Pippa Tshabalala Independent Scholar 37 Jukskei Drive Riverclub Johannesburg South Africa 2149 +27 (83) 326 7887 ABSTRACT Darkest Africa, the imagining of colonial fantasy, in many ways still lives on. Popular cultural representations of Africa often draw from the rich imagery of the un-charted, un-knowable ‗other‘ that Africa represents. When Capcom made the decision to set the latest instalment of its Resident Evil series in an imagined African country, it was merely looking for a new, unexplored setting, and they were therefore surprised at the controversy that surrounded its release. The 2009 game Resident Evil 5 was accused of racially stereotyping the black zombies and the white protagonist. These allegations have largely been put to rest, as this was never the intention of Capcom in developing the game or selecting the setting. However, the underlying questions remain: How is Africa represented in the game? How does the figure of the zombie resonate within that representation? And why does this matter? Keywords Post-Colonial, Zombie, Africa, Game, Resident Evil 5 ―The earth seemed unearthly. We are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster, but there – there you could look at a thing monstrous and free. It was as unearthly as the men were... No they were not inhuman. Well, you know that was the worst of it – this suspicion of their not being inhuman.‖ Joseph Conrad – Heart of Darkness Darkest Africa, the imagining of colonial fantasy, in many ways still lives on. -

Capcom Integrated Report 2019

The Head of Development Discusses Strategy Taking on the global market as a Japanese hit maker armed with world-class quality. Yoichi Egawa Director and Executive Corporate Officer In charge of Consumer Games Development and Pachinko & Pachislo Business Divisions of the Company Outfitting Our Bolstering Development Environment The world’s Development Personnel most entertaining Enhancing our development studios games Top core members Concentrate development divisions, increase mobility and leadership Repeated achievements Proprietary Core members development tools Selected to direct rereleases or other titles RE Engine enhances quality Bolstered and development efficiency Mid-career and younger employees title lineup (core training framework) Adoption of latest technologies Training programs Support from more senior members World-class, cutting-edge 3D New graduates scanning, motion capture and VR 41 CAPCOM INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Value Creation Story Medium- to Long-Term Latest Creative Report Foundation for Financial Analysis and Growth Strategy Sustainable Growth (ESG) Corporate Data Development Aiming for sustainable growth by Development Game development engines evolve Policy creating and developing popular IPs Organization in-step with games; maintaining Characteristics an environment that enables In the past three years of overseeing development, my goal has been to ensure the world’s highest quality, working under the philosophy the pinnacle of craftsmanship of standing up and facing whatever may come. The missions we One of Capcom’s -

Resident Evil 4 Pc Free Download Full Version Free Download Games

resident evil 4 pc free download full version Free Download Games. Resident Evil 4 HD Edition (2004/ENG/RePack From NBB) 2004 | PC | English | Developer: Capcom and Sourcenext | Publisher: Ubisoft Entertainment | 4.59GB Genre: Action / Horror / 3D / 3rd Person Description: Leon S. Kennedy, familiar to all fans of the series, will once again be at the center of the plot. But this time it will not withstand a zombie, a corporation created by Umbrella, and the terrible sacrifices of the unknown parasite Las Plagas. In the PC version is dashing twirled detective story would be embellished with new details. Players are waiting for 5 additional chapters with an unexpected plot twist, because the main character will be Ada Wong, who mysteriously disappeared six years ago. Also among the many bonuses new weapons and unique costumes for the characters in the game. Features: It started . a long time. Rakunsky hell is left behind. Six years have passed since the destruction of the city and all its inhabitants, has long ceased to be human. Leon S. Kennedy, formerly served in the Raccoon City Police and the last from the beginning to the end of the nightmare of the second part of Resident Evil, found a quiet operation. At the very least, the service in a secret compartment under the president of the country no big deal as long as the head of state is not kidnapped daughter. The investigation led by Leon in the European godforsaken village. Well, it could be worse than the bearded types of guns, stolen presidential child* It seems nothing, but the village was not only forgotten, but the damned .