Plastics, the Circular Economy and Global Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waste Minimisation

Waste Minimisation An Environmental Good Practice Guide For Industry This guide will help industry and the Environment Agency move forward together to minimise waste and achieve national environmental goals WASTE MINIMISATION An Environmental Good Practice Guide for Industry “The cost of your waste is not so much the cost of getting rid of it as the value of what you are getting rid of!” Published by the Environment Agency April 2001, to help business achieve sustainable practice through waste minimisation. Revised edition April 2001. First published April 1998. i Waste Minimisation Good Practice Guide Environment Agency April 2001 FOREWORD Minimise waste – maximise profit The way we use our planet’s natural resources is now widely recognised as one of the root causes of many environmental problems. Waste and industrial emissions have a major impact on the environment both nationally and globally. Effects such as global warming, ozone depletion, acid rain, air and water pollution are all derived from local emissions, but the resources consumed may be mined and manufactured from anywhere in the world. From extraction to consumption the global economy consumes vast quantities of raw materials, water and energy. In the UK some 600 million tonnes of raw materials, excluding water, are used each year. More than 90 per cent of the resources we consume are either thrown away as wastes or discharged to the environment as effluent or air emissions. Since the Environment Agency first published this guide in 1998, waste minimisation has become an established business practice for many organisations and thousands of businesses have now implemented waste reduction programmes. -

Waste Management

10 Waste Management Coordinating Lead Authors: Jean Bogner (USA) Lead Authors: Mohammed Abdelrafie Ahmed (Sudan), Cristobal Diaz (Cuba), Andre Faaij (The Netherlands), Qingxian Gao (China), Seiji Hashimoto (Japan), Katarina Mareckova (Slovakia), Riitta Pipatti (Finland), Tianzhu Zhang (China) Contributing Authors: Luis Diaz (USA), Peter Kjeldsen (Denmark), Suvi Monni (Finland) Review Editors: Robert Gregory (UK), R.T.M. Sutamihardja (Indonesia) This chapter should be cited as: Bogner, J., M. Abdelrafie Ahmed, C. Diaz, A. Faaij, Q. Gao, S. Hashimoto, K. Mareckova, R. Pipatti, T. Zhang, Waste Management, In Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. Waste Management Chapter 10 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................. 587 10.5 Policies and measures: waste management and climate ....................................................... 607 10.1 Introduction .................................................... 588 10.5.1 Reducing landfill CH4 emissions .......................607 10.2 Status of the waste management sector ..... 591 10.5.2 Incineration and other thermal processes for waste-to-energy ...............................................608 10.2.1 Waste generation ............................................591 10.5.3 Waste minimization, re-use and -

WASTE MANAGEMENT ARRANGEMENT of SECTIONS PART I Preliminary SECTION 1

CHAPTER 65:06 WASTE MANAGEMENT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I Preliminary SECTION 1. Short title 2. Interpretation PART II Establishment of Department 3. Establishment of Department 4. Staff of Department 5. Identity card of an officer PART III Functions of Department 6. Functions of Department 7. Annual Report 8. Qualifications of officers and managers PART IV Waste Management Plans 9. Local and national waste management plans 10. Waste recycling plan 11. Litter plan PART V Registration and Licensing of Waste Carriers 12. Registration of waste carrier 13. Licensing of waste carriers PART VI Registration of Waste Disposal Sites and Licensing of Waste Management Facilities 14. Registration of waste disposal sites 15. Unlicenced waste management facility prohibited 16. Licensing of waste management facility 17. Consultation 18. Conditions of waste management facility licence 19. Variation of conditions 20. Transfer of waste management facility licence 21. Suspension of waste management facility licence 22. Revocation of waste management facility licence 23. Surrender of waste management facility licence 24. Exemption from holding licence 25. Public register of issued waste management facility licences 26. Closure of facility by order of Minister Copyright Government of Botswana 27. Appeals 28. Offence and penalty PART VII Powers and Duties of Local Authorities 29. Collection of waste 30. Receptacles for household waste 31. Disposal of waste 32. Removal of waste 33. Power to recycle waste PART VIII Litter 34. Prohibition to litter 35. Abatement of litter 36. Dumping of litter 37. Principal Litter Authority 38. Notices for depositing litter PART IX Enforcement Powers 39. Power to obtain information 40. Power of search and seizure 41. -

What Is Controlled Waste?

Controlled waste fact sheet What is controlled waste? Under the Environmental Protection (Controlled Waste) Regulations 2004 Waste means any: (the Regulations): a) discarded, rejected, unwanted, surplus or abandoned matter; or 2. Controlled waste means any matter b) otherwise discarded, rejected, that is — unwanted, surplus or abandoned a) within the definition of waste in matter intended for: the NEPM for the Movement of (i) recycling, reprocessing, Controlled Waste between recovery, reuse, or States and Territories;* and purification by a separate b) listed in Schedule 1 … operation from that which produced the matter; or (ii) sale, whether of any value or not. 3. (4) Subject to subregulations (5) Is my waste a controlled waste? and (6), these regulations apply to a controlled waste that is produced by or To determine if waste is a controlled as the result of — waste, information about its a) an industrial or commercial composition, pH, flashpoint and/or the activity; process that generated the waste may b) a medical, nursing, dental, be required. veterinary, pharmaceutical or For some waste, knowing how it was other related activity; generated is sufficient to establish c) activities carried out on or at a whether it is a controlled waste; for laboratory; or d) an apparatus for the treatment of example, waste from a septic tank. sewage. However, for certain waste, chemical analysis is needed to determine the *Under the National Environment composition of the waste and identify Protection (Movement of Controlled whether it is a controlled waste as Waste between States and Territories) listed in Schedule 1 of the Regulations. Measure: If a waste has been determined to be a controlled waste listed in Schedule 1 of the Regulations, it can be found on the waste category list — a quick- reference guide to recording controlled waste in short-form for tracking purposes. -

Environmental Management and Pollution Control (Waste Management) Regulations 2010

Contents (2010 - 104) Environmental Management and Pollution Control (Waste Management) Regulations 2010 Long Title Part 1 - Preliminary 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Interpretation 4. Application Part 2 - Management of Controlled Waste 5. Controlled wastes 6. General responsibilities 7. Production, storage and treatment of controlled waste 8. Disposal of controlled waste Part 3 - Management of General Waste 9. Disposal of general waste Part 4 - Miscellaneous 10. Approved management method 11. Prohibited activities at facilities 12. Environmental approvals 13. Transitional and savings provisions 14. Legislation rescinded Schedule 1 - Legislation rescinded Environmental Management and Pollution Control (Waste Management) Regulations 2010 Version current from 1 January 2017 to date (accessed 17 October 2018 at 15:45) Environmental Management and Pollution Control (Waste Management) Regulations 2010 I, the Governor in and over the State of Tasmania and its Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia, acting with the advice of the Executive Council, make the following regulations under the Environmental Management and Pollution Control Act 1994 . 25 October 2010 PETER G. UNDERWOOD Governor By His Excellency's Command, D. J. O'BYRNE Minister for Environment, Parks and Heritage PART 1 - Preliminary 1. Short title These regulations may be cited as the Environmental Management and Pollution Control (Waste Management) Regulations 2010 . 2. Commencement These regulations take effect on the day on which their making is notified in the Gazette. -

INTEGRATED SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT for LOCAL GOVERNMENTS a Practical Guide

INTEGRATED SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENTS A Practical Guide Improving solid waste management is crucial for countering public health impacts of uncollected waste and environmental impacts of open dumping and burning. This practical reference guide introduces key concepts of integrated solid waste management and identifi es crosscutting issues in the sector, derived mainly from fi eld experience in the technical assistance project Mainstreaming Integrated Solid Waste Management in Asia. This guide contains over 40 practice briefs covering solid waste management planning, waste categories, waste containers and collection, waste processing and diversion, landfi ll development, landfi ll operations, and contract issues. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacifi c region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to a large share of the world’s poor. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by members, including from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. INTEGRATED SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENTS A Practical Guide ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines 9 789292 578374 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK www.adb.org Tool Kit for Solid Waste Management in Asian_COVER.indd 1 6/1/2017 5:14:11 PM INTEGRATED SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENTS A Practical Guide Improving solid waste management is crucial for countering the public health impacts of uncollected waste as well as the environmental impacts of open dumping and burning. -

Disposing of Clinical and Dental Waste

FEATURE CORE CPD: Disposing of clinical ONE HOUR and dental waste By Rebecca Allen1 ental professionals Defining different types of waste Amalgam waste is waste consisting are under increasing Clinical waste is defined as ‘any waste which of amalgam in any form and includes pressure to understand consists wholly or partly of human or animal all other materials contaminated with and adhere to clinical tissue, blood or other body fluids, excretions, amalgam. Amalgam waste is hazardous waste regulations. Proper drugs or other pharmaceutical products, due to the potential of harm to humans management and disposal swabs or dressings, syringes, needles or other and the environment caused by mercury. Dof clinical waste is vital and there is strict sharp instruments’. This type of waste may Any amalgam waste should be placed in a legislation in place to prevent harm being prove hazardous to any person coming into specialist dental container, with a mercury caused to the environment and to contact with it unless it is rendered safe. suppressant, to prevent the risk of harm to human health. Waste is defined as ‘hazardous’ when the your dental team from the mercury vapours. To dispel some of the misconceptions waste itself or the material or substances In addition all dental practices should have around clinical waste and to enable it contains are harmful to humans or the an amalgam separator installed to capture any organisations to clearly verify if they need environment. The other main waste stream amalgam particulates in waste water. These to take further steps to become compliant is known as offensive waste, which primarily should be fitted both to the dental chair and with all regulations, this article outlines contains waste that is considered unpleasant dirty sink. -

Environmental Protection (Controlled Waste) Regulations 2004

Western Australia Environmental Protection Act 1986 Environmental Protection (Controlled Waste) Regulations 2004 As at 24 Jan 2017 Version 01-c0-00 Extract from www.slp.wa.gov.au, see that website for further information Western Australia Environmental Protection (Controlled Waste) Regulations 2004 Contents Part 1 — Preliminary 1. Citation 1 2. Terms used 1 3. Application of regulations 4 Part 2 — Licensing Division 1 — General matters 4. Application for licence 6 5. Licensing 6 6. Conditions 7 7. Refund of fee 8 8. Validity of licence 9 9. Renewal of licence 9 10. Cancellation or suspension of, refusal to renew, licence 9 Division 2 — Carriers 11. Certain carriers to be licensed 11 12. Refusal of licence 11 13. Sub-contractors 11 14. Employment of unlicensed driver to transport bulk controlled waste 12 15. Notification of employment of licensed drivers 12 16. Interstate carriers 12 Division 3 — Drivers 17. Drivers to be licensed 13 18. Refusal of licence 13 As at 24 Jan 2017 Version 01-c0-00 page i Extract from www.slp.wa.gov.au, see that website for further information Environmental Protection (Controlled Waste) Regulations 2004 Contents 19. Driver identification card 14 20. Recognition of licence issued in another State or a Territory 14 Division 4 — Vehicle or tank 21. Vehicles and tanks of carriers to be licensed 15 22. Application for licence and inspection of vehicle or tank 15 23. Issue of licence 16 24. Validity of licence 16 Division 5 — Assignment of carrier’s business and transfer of licence 25A. Terms used 17 25B. Assignment of carrier’s business 17 25C. -

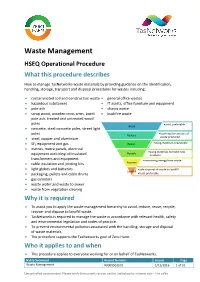

Waste Management HSEQ Operational Procedure What This Procedure Describes

Waste Management HSEQ Operational Procedure What this procedure describes How to manage TasNetworks waste materials by providing guidance on the identification, handling, storage, transport and disposal procedures for wastes including: contaminated soil and construction waste general office wastes hazardous substances IT assets, office furniture and equipment pole ash sharps waste scrap wood, wooden cross arms, burnt bushfire waste pole ash, treated and untreated wood poles •most preferable Avoid concrete, steel concrete poles, street light •lowering the amount of poles Reduce steel, copper and aluminium waste produced •using materials repeatedly SF6 equipment and gas Reuse metres, metre panels, electrical •using materials to make new Recycle equipment excluding oil insulated products transformers and equipment •recovering energy from waste cable insulation and jointing kits Recover light globes and batteries •safe disposal of waste to landfill Landfill packaging, pallets and cable drums •least preferable gas cylinders waste water and waste to sewer waste from vegetation clearing Why it is required To assist you to apply the waste management hierarchy to avoid, reduce, reuse, recycle, recover and dispose to landfill waste. TasNetworks is required to manage the waste in accordance with relevant health, safety and environmental legislation and codes of practice. To prevent environmental pollution associated with the handling, storage and disposal of waste materials. The procedure supports the TasNetworks goal of Zero -

Chapter 7: Other Wastes

East Sussex and Brighton & Hove Waste Local Plan Part 2: IMPLEMENTING THE WASTE LOCAL PLAN STRATEGY Chapter 7: Other wastes 103 East Sussex and Brighton & Hove Waste Local Plan Chapter 7: Other wastes Introduction 7.1 Other wastes include hazardous and clinical wastes, which require more stringent handling and treatment than other ‘controlled’55 wastes, and mineral, agricultural and sewage wastes, which are not classified as controlled wastes. This chapter describes the types of more specialised wastes that are produced in the Plan area, together with relevant policies against which proposals will be assessed by the WPAs. Applications will be assessed against the provisions of the whole Development Plan. This chapter deals with the following types of waste: (i) Mineral Waste (ii) Hazardous (Special) and Difficult waste (iii) Clinical Waste (iv) Wastewater and Sewerage (v) Landspreading of Liquid Wastes and Dredgings (vi) Liquid Waste Facilities (vii) Agricultural and Farm Waste (viii) Animal Carcass Waste (ix) Nuclear and Radioactive Waste (x) Contaminated Land Waste (i) Mineral Waste 7.2 Mineral waste mainly comprises overburden waste, unusable rock and process waste from screening and washing. There are few markets for these materials and they are usually incorporated into the restoration of the site. At sand and gravel sites with washing facilities silt is deposited in lagoons while at other mineral workings waste is deposited within the boundary of the site, as backfilling or screening. This is an appropriate re-use of the material provided it contributes to the beneficial restoration of the site or the temporary screening of operations. Opportunities for blending of mineral waste may arise if soil/compost materials are being produced on-site, the mixture yielding soil forming materials. -

(Specially Controlled Waste) Regulations, 2010

GUERNSEY STATUTORY INSTRUMENT The Waste Control and Disposal (Specially Controlled Waste) Regulations, 2010 Made 4 Coming into Operation 1"' June, 201 0 Laid before the States THE DIRECTOR OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH AND POLLUTION REGULATION, in exercise of the powers conferred on her by sections 26 and 34 of the Environmental Pollution (Waste Control and Disposal) b ordinancea, 20 10, section 72 of the Environmental Pollution (Guernsey) Law, 2004 and of all other powers enabling her in that behalf, hereby orders:- Interpretation. 1. (1) In these Regulations, unless the context otherwise requires - "commercial waste" means waste arising from any activity carried on by way of business, and includes agricultural and horticultural waste other than such waste arising from use of the curtilage of a dwelling house for purposes connected with the use of that dwelling house, a Approved by resolution of the States on 28t" April, 201 0. Order in Council No. XI11 of 2004. "Director" means the person appointed as Director of Environmental Health and Pollution Regulation under section 4 of the Law, "dwelling house" means a building or part of a building used as a permanent residence for members of one household, and includes the curtilage of such a building, but does not include a hotel, hospital or other place where persons may temporarily live, "enactment" includes an instrument and any Directive, Regulation or Decision of any institution of the European Union, "European Waste Catalogue" means the list of wastes pursuant to Article l(a) of Directive -

Decision-Makers Guide (PDF)

© 2000 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First printing June 2000 This report has been prepared by the staff of the World Bank. The judgments expressed do not necessari- ly reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors or of the governments they represent. The material in this publication is copyrighted. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly. Permission to photocopy items for internal or personal use, for the internal or personal use of specific clients, or for educational classroom use, is granted by the World Bank, provided that the appropriate fee is paid directly to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, U.S.A., tele- phone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470. Please contact the Copyright Clearance Center before photocopying items. For permission to reprint individual articles or chapters, please fax your request with complete informa- tion to the Republication Department, Copyright Clearance Center, fax 978-750-4470. All other queries on rights and licenses should be addressed to the World Bank at the address above or faxed to 202-522-2422. Cover photo by unknown. Contents Foreword v Solid Waste Incineration 1 Institutional Framework 2 Waste as Fuel 5 Economics and Finance 7 Project Cycle 10 Incineration Technology 11 iii Foreword The Decision Makers’ Guide to Incineration of Municipal the project is not institutionally, economically, techni- Solid Waste is a tool for preliminary assessment of the cally, or environmentally feasible.