A:\Mullally Text.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assisted Suicide Debate Revived VATICAN POST I Church Condemns Margo Macdonald MSP’S Latest Attempt to Bring Issue Before Scottish Parliament by Ian Dunn

CHRISTINE GLEN begins covering BISHOP TOAL hopes a concert with the arts for the SCO by looking at Michelle McManus for St Columba’s the Archdiocese of Glasgow Arts Cathedral encourages visitors to Project and Lentfest. Pa ge 12 Argyll and the Isles Diocese. Page 4 No 5451 www.sconews.co.uk Friday January 27 2012 | £1 Assisted suicide debate revived VATICAN POST I Church condemns Margo MacDonald MSP’s latest attempt to bring issue before Scottish Parliament By Ian Dunn THE Catholic Church in Scotland has condemned Margo MacDon- ald’s latest attempt to legalise assisted suicide, just a year after her last effort was roundly defeated in the Scottish Parliament. The Independent Lothians MSP unveiled a new consultation on the issue—which pushes for ‘a friend at the end’—at the Scottish Parliament on Tuesday, despite the failure of her first MGR PETER SMITH bid to make it legal for the ill and the of Glasgow to take up dying to seek help to kill themselves. role at UN in New York Prior to the defeat of Ms MacDon- ald’s last bill, Cardinal Keith O’Brien, helping Vatican nuncio Britain’s most senior Catholic clergy- man, warned that it would inevitably Page 3 lead to repeated attempts to change the law. INSIDE YOUR SCO Democratic process NEWS pages 1-9 Ms MacDonald’s new proposals come OPINION pages 10-11 in spite of the comprehensive defeat of the previous End of Life Assistance FEATURES pages 12-13, 21 (Scotland) Bill in a free vote at Holy- LETTERS page 14 rood just over a year ago. -

Open House Conference 2019 Editorial Unlocking Potential

Comment and debate on faith issues in Scotland June/July 2019 www.openhousescotland.co.uk Issue No 282 £2.50 Open House conference 2019 Editorial Unlocking potential The Open House conference on 1st June was remarkable for conference bear this out. They are both familiar and new. A several reasons. People had to be turned away at the door. greater role for lay people, meaningful consultation, Bishops, lay people, priests and religious sat down together to accountability and shared decision making are familiar themes discuss new directions for the Catholic Church in Scotland. from renewal programmes which responded to the Council’s The format of the day created a pattern of respectful listening vision of integrating clergy, religious and laity within the and sharing which resulted in the overwhelming conclusion common framework of one people of God. Now we see them that the status quo is not an option. in the context of a developing synodal style in local churches The format was shaped by the belief that the people in the around the world. room had the collective wisdom and insight to address the task Bishop Brendan Leahy gave a vivid account of the Limerick in hand. The challenge was to unlock it. Participants listened diocesan synod of 2016. It drew on many skills and involved together to short contributions from people who are already widespread consultation and communication with more than taking the church in new directions, and shared their responses 5,000 people over two years. The themes which surfaced were in a series of round table conversations. -

Catholic Archives 1981

CATHOLIC ARCHIVES No. 1 1981 CONTENTS Foreword His Lordship Bishop B. FOLEY 2 The Catholic Archives Society L.A.PARKER 3 Editorial Notes 5 Reflections on the Archives of the English Dominican Province B. BAILEY O.P. 6 The Scottish Catholic Archives M. DILWORTH O.S.B. 10 The Archives of the English Province of the Society of Jesus F.O. EDWARDS S.J. 20 Birmingham Diocesan Archives J.D.McEVILLY 26 The Archives of the Parish of St. Cuthbert, Durham City J.M.TWEEDY 32 The Lisbon Collection at Ushaw M. SHARRATT 36 Scheme of Classification for Archives of Religious Orders 40 Scheme of Classification for Diocesan Archives 43 The Annual Conference 1980 48 Illustrations: Mgr. Butti, Blairs College, 1930 16 Fr. W.J. Anderson, 1959 17 FOREWORD I warmly welcome this new publication: Catholic Archives. When I first learned of the founding of the Catholic Archives Society I felt a sense of deep relief, as many must have done. Every now and then one had heard of the irreparable loss of Catholic documents and wondered what future generations would think of us for allowing such things to happen. Mgr. Philip Hughes once stated that more than one third of the Catholic papers listed in the last century by the Historical Manuscripts Commission had been lost by the time he became archivist at Westminster. Lately, indeed, something has been done to avert further losses. The valuable papers of the Old Brotherhood still remaining have been gathered and bound and deposited for safe-keeping. A number of dioceses are now placing their records on permanent loan in county record offices established since the last war. -

Don't Just Give Up, but Live MERCY This Lent

Lord, Let Glasgow Flourish by the preaching of Thy Word and the praising of Thy Name FEBRUARY 2016 JOURNAL OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF GLASGOW 70p Royal’s SCIAF’s Face E D face of Wee Box of an I S mercy angel N I page 5 pages 6 –7 page 11 Don’t just give up, but live MERCY this Lent In the Year of Mercy, POPE FRANCIS calls for the season of Lent, which begins with Ash Wednesday on 10 February, to be lived more intensely as a privileged moment to celebrate and experience God’s mercy. Presenting Mary as the “perfect icon of the Church which evangelises” he invites the whole Church to listen more attentively to God’s voice and be prepared to put into practice the corporal and spiritual works of mercy GOD’S mercy transforms It is the unprecedented and scan - human hearts. It enables us, dalous mystery of the extension in through the experience of a time of the suffering of the Innocent faithful love, to become mer - Lamb, the burning bush of gratu - This illusion can also be seen in itous love. Before this love, we can, the sinful structures linked to a Jade Tobia of St Thomas ciful in turn. Aquinas Secondary, like Moses, take off our sandals, es - model of false development based Jordanhill, working on In an ever new miracle, divine pecially when the poor are our on the idolatry of money, which the banner which she mercy shines forth in our lives, in - brothers or sisters in Christ who are leads to lack of concern for the fate will help to carry at the spiring each of us to love our neigh - suffering for their faith. -

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No. 23 June 2021 INSIDE THIS ISSUE - Tributes to the lifes of Bishop Vincent Logan, Mgr John Harty & Sr Deirdre O’Brien Substantial savings declared and a new parish levy is announced Lawside closes as strategic review looks to future of the diocese Addressing the clergy this week, Bishop Stephen revealed the perilous state of di- ocesan finances and the steps that are al- ready being taken to address the growing problem. As the impact of the pandemic becomes clearer, there are still many questions in the Church about the ‘new normal’ and, in par- ticular, the Church’s future after lockdown with attendances at Mass still limited, not only by social distancing, but also insecu- rities about the effects of the virus in the FOR SALE - DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY longer term. At an early stage during lock- down, Bishop Stephen made a financial appeal, his first in 42 years as a priest, for support for parishes and the wider Church community. With the churches closed, col- lections have fallen dramatically and new methods were needed to be set up for on- line giving and contactless payments in our With sights set on a fairer and more sus- “The Immaculate Heart of Mary Sis- churches. tainable system, Bishop Stephen said, “the ters are also to move, from Lawside to the Bishop Stephen said, “As you will know, Diocesan levy has not been touched for church house at St Mary’s Forebank, within the Diocese in recent years, for all sorts over twenty years and, due to the above- the city of Dundee.” of reasons, has been plunging deeper and mentioned increasing demands on finan- deeper into debt. -

Scottish Catholic Historical Association Newsletter 1, January

Scottish Catholic Historical Association Newsletter, May 2009 Contents 2. Upcoming Conference 1. Welcome 2. Upcoming Conference SCHA Annual Conference 3. Contacts 4. The Innes Review ‘Diaspora’ 5. Seminar series th 6. Seminar reports 13 June 2009 7. SCA Projects: Scots College, Spain 8. Bookshop New College University of Edinburgh 1. Welcome Máirtín Ó Catháin (University of Central Lancashire) “Eulogising the Welcome to the second newsletter of the Scottish Catholic Irish in Scotland” Historical Association. S. Karly Kehoe (UHI Centre for It is being planned to supplement the Innes Review and History) “Highlanders and the Irish other activities of the Association. The past few months have in Nineteenth-Century Ontario” seen increased activity for the Association, with the new series of evening seminars, based at the Scottish Catholic Andrew Nicoll (Scottish Catholic Archives, Columba House, Edinburgh. Reports on the last Archives) “The Diaspora Holdings three are found in this newsletter. of the Scottish Catholic Archives” The Association has also launched a website with the assistance of the Scottish Catholic Archives and it can be Elizabeth Ritchie (UHI Centre for found by going to the SCA website at History) “‘Those nasty Uist people’: www.scottishcatholicarchives.org.uk and clicking on the Migration and Religion” ‘Historical Association’ link. Alasdair Roberts (Independent S Karly Kehoe, Newsletter and Seminar Co-ordinator Scholar) “MacDonalds at Home and Abroad” 3. Contacts Scottish Catholic Historical Association Location and time: Secretary: Dr Andrew Newby, School of Divinity, History and Philosophy, Crombie Annexe, Meston Walk, King's New College, University of College, University of Aberdeen, Old Aberdeen, AB24 3FX Edinburgh Scottish Catholic Archives Saturday 13th June 9:30-3:15 Columba House, 16 Drummond Place, Edinburgh EH3 6PL. -

Proceed with Due Caution

WIN A TRIP TO JOIN THE GRANDPARENTS’ PILGRIMAGE AT KNOCK STARTING NEXT WEEK No 5289 Medjugorje marks 30th anniversary of visions Pages Testimony from lay Catholic, priest and religious. Vatican still to decide 12-13 No 5421 www.sconews.co.uk Friday June 24 2011 | 90p Proceed with due caution NEW EVANGELISATION I Church urges the use of prudence and wisdom in laws to govern football fans By Martin Dunlop THE Catholic Church has urged the Scottish Government to show suitable caution as it presses ahead to bring in new legislation before the football season begins next month. As the SCO went to press, the Scottish Parliament was set to vote on the Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications Bill, BISHOP TARTAGLIA a bill that would increase jail terms to a maximum of five years for those found urges lay Catholics guilty of abusive or sectarian behav- to get involved ahead iour, whether they are watching match- of next year’s synod es at the stadium, in a pub or making comments online. on behalf of the The justice committee at Holyrood, Scottish bishops however, has raised concern that the proposed legislation is being rushed Page 3 and Bishop Philip Tartaglia of Paisley, on behalf of the Scottish Bishops, said this week that ‘enacting laws and poli- EUCHARISTIC ADORATION cies aimed at resolving such problems must be pursued with prudence and wisdom to ensure that measures are GERALD WARNER suitable and proportionate for the says restoring the problem they seek to address.’ Feast of Corpus Christi Consultation would be a step in the The justice committee quizzed police, church, legal and football representa- right direction tives ahead of Thursday’s vote in par- liament, and the Catholic Bishops’ Page 10 Conference of Scotland submitted its own statement to the committee. -

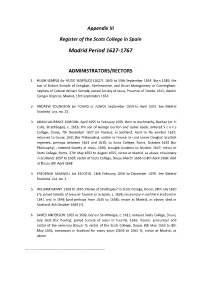

Appendix III : Register of the Scots College in Spain

Appendix III Register of the Scots College in Spain Madrid Period 1627-1767 ADMINISTRATORS/RECTORS 1. HUGH SEMPLE (or HUGO SEMPILIO) (1627). 1633 to 13th September 1654. Born 1589, the son of Robert Semple of Craigbait, Renfrewshire, and Grizel Montgomery or Cunningham; nephew of Colonel William Semple; joined Society of Jesus, Province of Toledo, 1615; died in Colegio Imperial, Madrid, 13th September 1654. 2. ANDREW YOUNGSON (or YOUNG or JUNIO). September 1654 to April 1655. See Madrid Students’ List, no. 13. 3. ADAM LAURENCE GORDON. April 1655 to February 1656. Born in Auchmathy, Buchan (or in Cults, Strathbogie), c. 1616, the son of George Gordon and Isabel Leesk; entered S c o t s College, Douai, 7th December 1627 (in Poetry); in Scotland, April to No vember 1631; returned to Douai, 1631 (for Philosophy); soldier in France, in Lord James Douglas’ Scottish regiment, perhaps between 1631 and 1635; to Scots College, Rome, October 1635 (for Philosophy) ; entered Society of Jesus, 1636; brought students to Madrid, 1647; rector of Scots College, Rome, 27th May 1652 to August 1655; rector at Madrid, as above; missionary in Scotland, 1657 to 1665; rector of Scots College, Douai, March 1666 to 8th April 1668; died at Douai, 8th April 1668. 4. FREDERICK MAXWELL (or ESCOTO). 18th February 1656 to December 1659. See Madrid Students’ List, no. 2. 5. WILLIAM GRANT. 1659 to 1665. Native of Strathspey? to Scots College, Douai, 28th July 1620 (?); joined Society of Jesus in Tournai or in Spain, c. 1626; missionary in northern Scotland in 1641 and in 1646 (and perhaps from 1635 to 1658); rector at Madrid, as above; died in Scotland, 8th October 1689 (?). -

'I Will Be a Pilgrim for Christ'

More than 100 SCHOOLCHILDREN are MARY McGINTY talks to Peter Kearney Confirmed in St Mirin’s Cathedral, about the fund in his late wife’s name, to Paisley, as part of a month-long help mothers with cancer, ahead of programme in the diocese. Page 2 benefit dinner on May 19. Pa ges 12-13 No 5466 www.sconews.co.uk Friday May 11 2012 | £1 Headteachers get government reassurances By Martin Dunlop BISHOP Joseph Devine and Catholic headteachers in Scotland learned last week that the Scottish Government has no intention of forcing them to teach contrary to their religious beliefs. Speaking at the Catholic Headteachers’ Association of Scotland (CHAS) conference last Thursday, the day of the local council elections, Scottish Education Minister Mike Russell (below) spoke to the Motherwell bishop, bishop for education, and the educa- tors on the issue of same-sex ‘marriage.’ “It is not the intention of this government to force denominational schools, or anybody else, to teach something which is against their beliefs,” he said. “Nor would I personally, nor the government, permit any circumstances in which there is an interference in the right to speak the truth as an individual sees it, of course always with respect and fairness.” Mr Russell was speaking as the Scottish public awaits the outcome of a government consultation on legalising same-sex ‘mar- riage,’ a proposal that has been vehemently opposed by the Catholic Church. Michael McGrath, director of the Scottish Catholic Education Service, highlighted press ‘I will be a pilgrim for Christ’ coverage in England that criticised Catholic schools for having the ‘audacity’ to teach a vision of marriage founded on Church doc- IAuxiliary bishop for St Andrews and Edinburgh named; installation a key moment in transition period trine. -

Portrait of a Diocese

Portrait of a Diocese Maurice Taylor © 2012 Maurice Taylor, Emeritus Bishop of Galloway PORTRAIT OF A DIOCESE CONTENTS Pseudo-Preface 2 THE SUBJECT BEING PORTRAYED 3 PERSONAL 4 EARLY DAYS 6 THE PAPAL VISIT OF 1982 7 PASTORAL RENEWAL (i-ii) 8 (i) DIOCESAN QUESTIONNAIRE 8 (ii) “RENEW” 15 ALARMING STATISTICS 18 THE PRIESTS 20 RELIGIOUS 27 EDUCATION AND SCHOOLS 29 THE CELEBRATION OF MASS 32 THE SACRAMENTS 33 FUNERALS 39 ECUMENICAL RELATIONS 40 FINANCE 41 DEANERY BY DEANERY (i-iv) 43 (i) ST ANDREW’S DEANERY 43 (ii) ST JOSEPH’S DEANERY 48 (iii) ST MARY’S DEANERY 50 (iv) ST MARGARET’S DEANERY 55 A COMMUNITY OF COMMUNITIES? 58 Pseudo-Preface When you open a book and then discover that it has a Preface, does your heart not sink a little? Mine does. And the depth to which it sinks is in direct proportion to the number of pages in the Preface. One or two pages are tolerable, but some books can fill the prospective reader with gloom. Must I read the Preface? Will I not understand the book properly if I skip the Preface? Perhaps, if I enjoy the book, the Preface will be more interesting as a Postscript; and, if the book has been a struggle, I can close it without feeling that I have missed much by ignoring the Preface. These are the thoughts that often pass through my mind. So I spare my readers the necessity of either choosing conscientiously to read a long Preface or guiltily to skip it. By the way, when we speak of the “Preface” in the Mass, we are not speaking of something that precedes and leads us to the Eucharisitic Prayer, but the first part of the Eucharistic Prayer itself, a paean of praise and thanksgiving to God with the acclamation “Holy, Holy . -

Short History of the St. Vincent De Paul Society in Scotland – 1845-2020 by James Mckendrick I F St.V Ncen O T D Y E T Ie P C a O U S L

i f St.V ncen o t d y e t ie P c a o u S l s er e viens in sp S cotland Short History of the St. Vincent de Paul Society in Scotland – 1845-2020 by James McKendrick i f St.V ncen o t d y e t ie P c a o u S l s er e viens in sp S cotland Foreword At one point in his life as an Apostle, St Paul went with his colleague Barnabas to Jerusalem to visit the leading Christian figures there: Peter, James and John. He wanted to receive their endorsement, and he did. They had only one thing to add: “remember the poor” (Galatians 2:10). This, Paul said, was “the very thing I was eager to do.” That command, “remember the poor”, lives on and so does St Paul’s eagerness to fulfill it. This book tells the story of the continuing “eagerness” of the Society of St Vincent de Paul to engage in constant, unobtrusive, grass-roots, practical, “remembering” of the poor – who have not been magicked out of existence by social advances, but are always with us. James McKendrick’s succinct and attractive account tells of the Society’s origins in Paris in the 1830s, its establishment and progress and present activity in Scotland. If you are in Aberdeen, you can see the extent and human warmth of its work every Tuesday evening outside St Mary’s, Cathedral. That is just one of so many initiatives throughout Scotland. I am glad this book has been written. -

Report Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry

Bishops’ Conference of Scotland Report to the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry Redacted Version 28th April 2017 1 Table of Contents PREFACE ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The structure of the Catholic Church in Scotland ........................................................................................ 5 2. The Hierarchy BCS/Diocesan relationship with the religious Orders ........................................................ 15 3. The Hierarchy BCS/Diocesan involvement in the creation, oversight, governance and management of any children’s residential care establishments run by religious Orders. ................................................... 21 4. Consider a number of Catholic establishments and disclose the Church’s involvement over the time frame of the Inquiry ................................................................................................................................... 26 5. The Church’s role in connection with Kenmure St Mary’s after the De La Salle Brothers left in 1966 ..... 28 6. Involvement of local priests in placing children into care whether residential care or some form of foster care ............................................................................................................................................................ 30 7. The Church’s knowledge of the existence of abuse (whether physical, emotional or sexual) of children in the care of religious