Portrait of a Diocese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No.5 August 2015

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No.5 August 2015 DUNKELD LOURDES PILGRIMAGE 2015 - SOUVENIR EDITION Travellers return uplifted by prayerful pilgrimage The Rt. Rev. Stephen Robson Lourdes kick-started my faith Andrew Watson writes Over the years I have been asked to speak at Masses about my experience attending the Diocesan pilgrimage to Lourdes. This is something I have always been more than happy to do as it was an experience that profoundly changed my life. I hope that, in these columns, I can perhaps shine some “We said prayers for you” light on how that experience has actually continued to be of great value to me almost Photos by Lisa Terry three years since I last travelled with the Diocese of Dunkeld to Lourdes. Lourdes is not only a place that can strengthen and deepen the faith of the sick and elderly who go there, but impact the life of young Catholics in immeasurable ways. When I first signed up for Lourdes in 2008 I was 20 years old and just as nerv- ous as I was excited about making the pil- grimage there. This was the place where the Virgin Mary appeared to Bernadette and where so many miracles had occurred. ...in procession to the Grotto continued on page 6 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: News, views and coming events from around the diocese ©2015 DIOCESE OF DUNKELD - SCOTTISH CHARITY NO. SC001810 page 1 Saved Icon is Iconic for Saving Our Faith The story of the rescue of this statue is far from unique. Many medieval statues of our Lady, beloved by the people, we similarly rescued from the clutches of the Reform- ers. -

News from Tobias Parker Many Of

News from The Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham in Scotland www.ordinariate.scot Pilgrimage 2016 Issue Celebrating Saint Andrew in this▸ issue... Ordinariate Pilgrimage to St Andrews ? Pilgrimage ? New Ordinariate HE ORDINARIatE is on Monsignor Keith Newton writes: members TPilgrimage throughout the UK “Pilgrimage holds a special place ? Bl John Henry during this Jubilee Year of Mercy. in the Ordinariate of Our Lady Newman ‘miracle’ They began in North Wales at the of Walsingham. For many of us, ? New Ordinariate Shrine of St Winifrede at Holywell, pilgrimages to the shrine from Mass routine and as you read this, Mgr Keith which we take our name have been Newton, will be in Rome and central to our spiritual life. Loreto with a group of Ordinariate Pilgrims. “Our entry as members of the Ordinariate into the full communion of the Catholic ? First Ecumenical Church was in itself a pilgrimage Chapel in – travelling together, often at some Scotland personal cost, to answer God’s ? Mgr Newton’s call and to receive His grace. It is Scottish visit natural therefore that pilgrimage should be at the heart of our observance of the Year of Mercy.” The Apostle Andrew was the first disciple to follow Jesus. He was present during the Last Supper and in the Garden at Gethsemane. He saw the Risen ? The Oratory Christ after the Resurrection ? Lent Appeal and was amongst those who ? On-line Shopping received the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. According to ? Welcome tradition, Andrew left the Holy ? Holy Land and Land after Pentecost to spread Poland the Word in Greece and Asia ? Abbey establishes This will be followed by a Minor. -

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No. 18 December 2019 INDSIDE - Parish news stories; Lourdes reports, Our pilgrims in Spain and Italy, Schools and Youth News Emotional welcome for the Little Flower What a grace-filled event it was for our for everyone present. It seemed to everyone diocese to have the relics of St Therese of that her saintly presence was enough as she Lisieux visit us in our own St Andrews spoke in the silence of everyone’s heart. Cathedral in September. It was as though Therese, one of the most popular saints in Therese had come not for herself but for the history of the Church, had indeed come everyone in every diocese in Scotland and to visit us to inspire us, to encourage us, the people present were delighted that she and just to be present with us for a few days was really here in our Diocese of Dunkeld where she will listen to us and speak to us with devotees, young and old, who loved in the depths of our hearts. Never has the her and wished to spend some time in her Cathedral been so bedecked with so many physical and spiritual presence. Most of all beautiful roses, symbols of her great love to learn from her. The good humour spread Fr Anthony McCarthy, parish priest for God and her promise to all of her devo- quickly among the congregation, and the of Our Lady of Good Counsel, Broughty tees. sense of incredulity at her closeness was Ferry, died on Thursday 10th October, awesome. -

1 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

1 bus time schedule & line map 1 Priestland - Kilmarnock View In Website Mode The 1 bus line (Priestland - Kilmarnock) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Kilmarnock: 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM (2) Priestland: 4:51 AM - 10:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 1 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 1 bus arriving. Direction: Kilmarnock 1 bus Time Schedule 29 stops Kilmarnock Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM Loudon Avenue, Priestland Loudoun Avenue, Scotland Tuesday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM John Morton Crescent, Darvel Wednesday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM McIlroy Court, Scotland Thursday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM Murdoch Road, Darvel Friday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM Murdoch Road, Darvel Saturday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM Green Street, Darvel Temple Street, Darvel Hastings Square, Darvel 1 bus Info Fleming Street, Darvel Direction: Kilmarnock Stops: 29 Fleming Street , Darvel Trip Duration: 33 min Line Summary: Loudon Avenue, Priestland, John Dublin Road, Darvel Morton Crescent, Darvel, Murdoch Road, Darvel, Dublin Road, Scotland Green Street, Darvel, Temple Street, Darvel, Fleming Street, Darvel, Fleming Street , Darvel, Dublin Road, Alstonpapple Road, Newmilns Darvel, Alstonpapple Road, Newmilns, Union Street, Newmilns, East Strand, Newmilns, Castle Street, Union Street, Newmilns Newmilns, Baldies Brae, Newmilns, Queens Crescent, Isles Street, Scotland Greenholm, Mure Place, Greenholm, Gilfoot, Greenholm, Barrmill Road, Galston, Church Lane, East Strand, Newmilns Galston, Boyd -

Galloway's Bishop-Elect in Prayer Call

Year for CAMPAIGN LIFE SUPREME KNIGHT CONSECRATED 2017 launched honour LIFE begins at ladies returns to on Sunday. pro-life lunch. Glasgow. Page 3 Page 2 Page 8 No 5597 BLESSINGS ON THE FEAST OF ST ANDREW ON NOVEMBER 30 Friday November 28 2014 | £1 EUROPE TOLD BY POPE FRANCIS TO RESPECT LIFE By Ian Dunn POPE Francis told members of the European Parliament on Tuesday that they must end the treatment of ‘the unborn, terminally ill, and the elderly’ as objects and embrace a new fairer immigration policy of acceptance. In a second speech the same day, the Pope also told the Council of Europe that human trafficking was the new slavery of our age, depriving its victims of all dignity. The Holy Father was speaking at the European Parliament in Strasbourg during a brief visit meant to highlight his vision for Europe a quarter-century after St John Paul II travelled there to address a continent still divided by the Iron Curtain. “Despite talk of human rights, too many people are treated as objects in Europe: unborn, terminally ill, and the elderly,” the Pope told MEPs. “We’re too tempted to throwaway lives we don’t see as ‘useful.’ Upholding the dignity of the person means acknowledging the value of the gift of human life.” He said that ‘killing [children]… before they’re born is the great mistake that happens when technology is allowed to take over’ and is ‘the Pope Francis shakes hands with Martin Schulz, inevitable consequence of a throwaway culture.’ president of the European Parliament, while visiting the European Parliament in Strasbourg I Continued on page 6 Galloway’s bishop-elect in prayer call I Fr William Nolan, ‘gobsmacked’ over Pope Francis’ appointment, asks for parishioners to pray for him By Ian Dunn seeds of Faith so long ago,” The new bishop added that his experience in many pastoral situations, He said he was glad that his ordination parishioners were delighted for him. -

Richard G. Hewlett and Jack M. Holl. Atoms

ATOMS PEACE WAR Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission Richard G. Hewlett and lack M. Roll With a Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall and an Essay on Sources by Roger M. Anders University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London Published 1989 by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Prepared by the Atomic Energy Commission; work made for hire. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hewlett, Richard G. Atoms for peace and war, 1953-1961. (California studies in the history of science) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Nuclear energy—United States—History. 2. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission—History. 3. Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 1890-1969. 4. United States—Politics and government-1953-1961. I. Holl, Jack M. II. Title. III. Series. QC792. 7. H48 1989 333.79'24'0973 88-29578 ISBN 0-520-06018-0 (alk. paper) Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii List of Figures and Tables ix Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall xi Preface xix Acknowledgements xxvii 1. A Secret Mission 1 2. The Eisenhower Imprint 17 3. The President and the Bomb 34 4. The Oppenheimer Case 73 5. The Political Arena 113 6. Nuclear Weapons: A New Reality 144 7. Nuclear Power for the Marketplace 183 8. Atoms for Peace: Building American Policy 209 9. Pursuit of the Peaceful Atom 238 10. The Seeds of Anxiety 271 11. Safeguards, EURATOM, and the International Agency 305 12. -

Thecommunityplan

EAST AYRSHIRE the community plan planning together working together achieving together Contents Introduction 3 Our Vision 3 Our Guiding Principles 4 The Challenges 8 Our Main Themes 13 Promoting Community Learning 14 Improving Opportunities 16 Improving Community Safety 18 Improving Health 20 Eliminating Poverty 22 Improving the Environment 24 Making the Vision a Reality 26 Our Plans for the next 12 years 28 Our Aspirations 28 2 Introduction Community planning is about a range of partners in the public and voluntary sectors working together to better plan, resource and deliver quality services that meet the needs of people who live and work in East Ayrshire. Community planning puts local people at the heart of delivering services. It is not just about creating a plan or a vision but about jointly tackling major issues such as health, transport, employment, housing, education and community safety. These issues need a shared response from, and the full involvement of, not only public sector agencies but also local businesses, voluntary organisations and especially local people. The community planning partners in East Ayrshire are committed to working together to make a real difference to the lives of all people in the area. We have already achieved a lot through joint working, but we still need to do a lot more to make sure that everybody has a good quality of life. Together, those who deliver services and those who live in our communities will build on our early success and on existing partnerships and strategies to create a shared understanding of the future for East Ayrshire. -

December 2014

Inside this issue Advent 2014 Diocese of Galloway .................... 2 Bishops’ Conference of Scotland The Guardian Angel Window ...... 2 Scottish Catholic Safeguarding Service Diocese of Dunkeld ..................... 2 My First Year as NSC ................... 3 Diocese of Paisley ....................... 3 Archdiocese of STAE ................... 4 Safeguarding Diocese of Motherwell ................ 4 Archdiocese of Glasgow ………….. 4 Conferences in 2014 ................... 5 Training by the NSC ..................... 6 News Diocese of Aberdeen ................... 6 Diocese of Argyll and the Isles .... 6 SCSS Contact Details ................... 6 Scottish Catholic Safeguarding Service Dedicated to the Protection of the Guardian Angels On October 4 th the Naonal Parish Safeguarding Coordinators came together for the annual conference which this year was held at the Gillis Centre, in Edinburgh. During Mass, Bishop Joseph Toal blessed the new Guardian Angel Window Panel and dedicated SCSS to the protecon of the Guardian Angels. A prayer card with a picture of the window and the new Naonal Safeguarding Prayer together with a candle again replicang the image of the window was given to all delegates. SCSS also commissioned a larger candle for each Diocesan Safeguarding Advisory Group. At the end of the conference these candles were taken back to each Diocesan Office and have already been used at other more local safeguarding events and Safeguarding Advisory Group meengs. Message from Bishop Toal This is the first newsleer from Tina Campbell and the SCSS staff as she completes her first year in post. This is my first newsleer as President of SCSS and I would like to express my thanks to and appreciaon for all the volunteers across Scotland who give of their me so willingly in our parishes and in our Catholic sociees and organisaons to help children and the vulnerable and to ensure their safety while benefing from the Church's spiritual and pastoral ministry or while parcipang in its varied social acvies. -

Green Light Signals Quest for Auxiliary

Lord, Let Glasgow Flourish by the preaching of Thy Word and the praising of Thy Name JULY 2015 JOURNAL OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF GLASGOW 70p Joie de vivre! A SPIRIT of joy filled St Andrew’s Cathedral as children and young people with additional support needs joined Archbishop Philip Tartaglia for Mass. The theme ‘Rejoice’ reflected the Gospel passage of Mary’s visit to her cousin Elizabeth – whose child in her womb leapt for joy. The Archbishop spoke of the gifts of life and love and the great joy which the births of John the Baptist and Jesus brought to the world. He encouraged the young people to rejoice and reflect that joy in caring for others and looking after the world. Glasgow Lord Provost Sadie Docherty joined in the celebrations. Picture by Paul McSherry Green light Caritas Glasgow to get signals quest Award another bishop for auxiliary Pope Francis has agreed diocesan bishop’s closest col - with Bishop Joseph Devine the green light to his request, By Vincent Toal laborator, he is expected to be who moved to Motherwell in Archbishop Tartaglia has in - to provide an auxiliary involved in all pastoral proj - 1983. Bishop John Mone then vited people to write to him by bishop for the Arch- an auxiliary following his ects, decisions and diocesan served as auxiliary for four 15 August with preferred pages diocese of Glasgow fol - health scare at the beginning initiatives. years before his appointment names. lowing a request from of the year. With Glasgow embarked on to Paisley in 1988. He will then make a formal 6,7,10,11 Archbishop Philip In an ad clerum letter, sent a wide-ranging review of Although usually chosen submission to the Apostolic out this week, he stated: “I am parish pastoral provision, the from among the diocesan Nuncio who conducts a Tartaglia. -

Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theology Papers and Journal Articles School of Theology 2007 Classified timelines of ernacularv liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy Russell Hardiman University of Notre Dame Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article Part of the Religion Commons This article was originally published as: Hardiman, R. (2007). Classified timelines of vernacular liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy. Pastoral Liturgy, 38 (1). This article is posted on ResearchOnline@ND at https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article/9. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Classified Timelines of Vernacular Liturgy: Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy Russell Hardiman Subject area: 220402 Comparative Religious Studies Keywords: Vernacular Liturgy; Pastoral vision of the Second Vatican Council; Roman Policy of a single translation for each language; International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL); Translations of Latin Texts Abstract These timelines focus attention on the use of the vernacular in the Roman Rite, especially developed in the Renewal and Reform of the Second Vatican Council. The extensive timelines have been broken into ten stages, drawing attention to a number of periods and reasons in the history of those eras for the unique experience of vernacular liturgy and the issues connected with it in the Western Catholic Church of our time. The role and function of International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL) over its forty year existence still has a major impact on the way we worship in English. This article deals with the restructuring of ICEL which had been the centre of much controversy in recent years and now operates under different protocols. -

Allchurches Trust Beneficiaries 2020

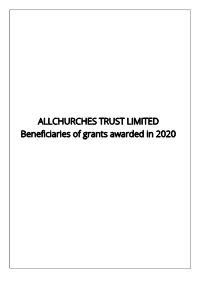

ALLCHURCHES TRUST LIMITED Beneficiaries of grants awarded in 2020 1 During the year, the charity awarded grants for the following national projects: 2020 £000 Grants for national projects: 4Front Theatre, Worcester, Worcestershire 2 A Rocha UK, Southall, London 15 Archbishops' Council of the Church of England, London 2 Archbishops' Council, London 105 Betel UK, Birmingham 120 Cambridge Theological Federation, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire 2 Catholic Marriage Care Ltd, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire 16 Christian Education t/a RE Today Services, Birmingham, West Midlands 280 Church Pastoral Aid Society (CPAS), Coventry, West Midlands 7 Counties (formerly Counties Evangelistic Work), Westbury, Wiltshire 3 Cross Rhythms, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire 3 Fischy Music, Edinburgh 4 Fusion, Loughborough, Leicestershire 83 Gregory Centre for Church Multiplication, London 350 Home for Good, London 1 HOPE Together, Rugby, Warwickshire 17 Innervation Trust Limited, Hanley Swan, Worcestershire 10 Keswick Ministries, Keswick, Cumbria 9 Kintsugi Hope, Boreham, Essex 10 Linking Lives UK, Earley, Berkshire 10 Methodist Homes, Derby, Derbyshire 4 Northamptonshire Association of Youth Clubs (NAYC), Northampton, Northamptonshire 6 Plunkett Foundation, Woodstock, Oxfordshire 203 Pregnancy Centres Network, Winchester, Hampshire 7 Relational Hub, Littlehampton, West Sussex 120 Restored, Teddington, Middlesex 8 Safe Families for Children, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire 280 Safe Families, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Tyne and Wear 8 Sandford St Martin (Church of England) Trust, -

Archdiocese of Glasgow

ARCHDIOCESE OF GLASGOW Curial Offices, 196 Clyde Street Glasgow, G1 4JY Tel: +44 (0) 141 226 5898 Fax: +44 (0) 141 225 2600 E-mail: [email protected] www.rcag.org.uk 17th August 2020 To the Head Teachers of Catholic Primary and Secondary Schools in the Archdiocese of Glasgow Dear Head Teachers, I am conscious that this is delicate moment in education due to the ongoing ramifications of the Covid-19 pandemic. Schools had to close for 5 months. During that time, teaching and learning was carried out remotely and supervised in person by parents and carers rather than by teachers. For more senior pupils and their teachers, there was the worry of the SQA examinations. I do hope your pupils were awarded the grades they deserved. Coming back to school, too, has been a significant epidemiological, educational and socio- political issue. Should schools re-open or not? Should they re-open partially or fully? How vulnerable are children and young people to the virus? How much could they spread it without knowing? How vulnerable are teachers and other school staff? What measures needed to be put in place in our schools to make them safe or at least to minimise risk? What will teaching and learning be like in these circumstances? These, and more, are questions that have been aired and debated ad infinitum over the summer weeks. I appreciate very much how these issues have impacted on the personal and professional well-being of teachers. I applaud the commitment of all teachers to their profession and to the children and young people that they educate so carefully and well.