Ewa Watershed Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anchialine Cave Biology in the Era of Speleogenomics Jorge L

International Journal of Speleology 45 (2) 149-170 Tampa, FL (USA) May 2016 Available online at scholarcommons.usf.edu/ijs International Journal of Speleology Off icial Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Life in the Underworld: Anchialine cave biology in the era of speleogenomics Jorge L. Pérez-Moreno1*, Thomas M. Iliffe2, and Heather D. Bracken-Grissom1 1Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Biscayne Bay Campus, North Miami FL 33181, USA 2Department of Marine Biology, Texas A&M University at Galveston, Galveston, TX 77553, USA Abstract: Anchialine caves contain haline bodies of water with underground connections to the ocean and limited exposure to open air. Despite being found on islands and peninsular coastlines around the world, the isolation of anchialine systems has facilitated the evolution of high levels of endemism among their inhabitants. The unique characteristics of anchialine caves and of their predominantly crustacean biodiversity nominate them as particularly interesting study subjects for evolutionary biology. However, there is presently a distinct scarcity of modern molecular methods being employed in the study of anchialine cave ecosystems. The use of current and emerging molecular techniques, e.g., next-generation sequencing (NGS), bestows an exceptional opportunity to answer a variety of long-standing questions pertaining to the realms of speciation, biogeography, population genetics, and evolution, as well as the emergence of extraordinary morphological and physiological adaptations to these unique environments. The integration of NGS methodologies with traditional taxonomic and ecological methods will help elucidate the unique characteristics and evolutionary history of anchialine cave fauna, and thus the significance of their conservation in face of current and future anthropogenic threats. -

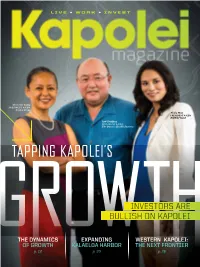

2013-2014 Kapolei Magazine.Pdf

LIVE + WORK + INVEST Christine Camp PRESIDENT & CEO, Avalon Group Alicia Moy PRESIDENT & CEO, HAWAI‘IGAS Art Ushijima PRESIDENT & CEO, The Queen’s Health Systems TAPPING KAPOLEI’S INVESTORS ARE BULLISH ON KAPOLEI THE DYNAMICS EXPANDING WESTERN KAPOLEI: OF GROWTH KALAELOA HARBOR THE NEXT FRONTIER p. 12 p. 20 p. 28 KAPOLEI 1 Live + Work + INVEST Live + Work + INVEST Investors are Pro t Grows Here Bullish on Kapolei ITH THE ECONOMY ON THE UPSWING, there has never been a better time to invest in Kapolei. The momentum W of a recovering economy is fueling interest in the region, where investment opportunities are made even more attractive with the availability of entitled, development-ready land. CONTENTS Investors remain bullish on Kapolei as the public and private sec- tors continue to build upon the groundwork that began with a vision FEATURES based on public policy - directing Oahu’s growth to the region. 6 Tapping Kapolei's Growth In this issue of Kapolei Magazine, we take a look at some of the many investors who are shaping the City of Kapolei and the 14 The City of Kapolei: Room to Grow broader Kapolei region. Their investments in these areas in the 20 State of Hawaii to Expand Kalaeloa Harbor region are attracting new businesses and creating jobs: 23 Bringing Essential City Services to Kapolei THE CITY OF KAPOLEI, where the public and private sector are defining the urban core; 28 Western Kapolei: The Next Frontier WESTERN KAPOLEI, where zoned land in three projects 36 Ewa: Bringing Services to a Booming is ready for development and -

Behavioral Responses of the Endemic Shrimp Halocaridina Rubra

Behavioral Responses of the Endemic Shrimp Halocaridina rubra (Malacostraca: Atyidae) to an Introduced Fish, Gambusia affinis (Actinopterygii: Poeciliidae) and Implications for the Trophic Structure of Hawaiian Anchialine Ponds1 Krista A. Capps,2 Caroline B. Turner,2 Michael T. Booth,2 Danica L. Lombardozzi,2 Scott H. McArt,4 David Chai,3 and Nelson G. Hairston Jr.2,5 Abstract: In the Hawaiian Islands, intentionally introduced exotic fishes have been linked to changes in native biodiversity and community composition. In 1905, the mosquito fish Gambusia affinis was introduced to control mosquitoes. Subsequently, G. affinis spread throughout the Islands and into coastal anchia- line ponds. Previous studies suggest that presence of invasive fishes in anchialine ponds may eliminate native species, including the endemic shrimp Halocaridina rubra. We examined effects of G. affinis on H. rubra populations in anchialine ponds on the Kona-Kohala coast of the island of Hawai‘i. In the presence of G. affinis, H. rubra exhibited a diel activity pattern that was not seen in fishless ponds. Shrimp in ponds with fish were active only at night. This pattern was ev- ident in anchialine ponds and in laboratory experiments. In laboratory predation experiments, G. affinis preferentially consumed smaller H. rubra, and in the field the H. rubra collected from invaded sites were larger than those from fishless ponds. Analysis of trophic position using stable isotope analyses showed that feeding of H. rubra was not significantly distinct from that of snails, assumed to feed at trophic level 2.0 on epilithic algae, but G. affinis was slightly omnivo- rous, feeding at tropic level 2.2. -

Index to Volume 53

Index to Volume 53 Author Index ABURTO-OROPEZA, OCTAVIo-see Sala et al. EWING, CURTIS ALLEN, MELINDA S., and GAIL M. MURAKAMI The Endemic Hawaiian Sap Beetles (Coleoptera: Liina'i Island's Arid Lowland Vegetation in Late Nitidulidae): Distribution, Ecological Shifts, and Prehistory, 88-112 Adaptation (abstract), 114-115 ARREOLA-RoBLES, JosE L.-see Sala et al. ASQUITH, ADAM-see Kido et al. ATAN, HUGO-see Osorio et al. FILARDI, CHRISTOPHER E., CATHERINE E. SMITH, ATKINSON, MARLIN J.-see Tarrant et al. ANDREW W. KRATTER, DAVID W. STEADMAN, and ATKINSON, SHANNON-See Tarrant et al. H. PRICE WEBB New Behavioral, Ecological, and Biogeographic Data BAILEy-BROCK, JULIE H. on the Avifauna of Rennell, Solomon Islands, 319 NeriIlidae of Hawai'i: Two New Records of 340 Interstitial Polychaetes, 299-304 FLETCHER, CHARLES H., III-see Harney et al. see also Brock et al. FOALE, SIMON BAILEy-BROCK, JULIE H., VERNON R. BROCK, and Local Ecological Knowledge and Biology of the Land RiCHARD E. BROCK Crab Cardisoma hirtipes (Decapoda: Gecarcinidae) Intrusion of Anchialine Species in the Marine at West Nggela, Solomon Islands, 37-49 Environment: The Appearance of an Endemic FOSTER, JAMIE S. Hawaiian Shrimp, Halocaridina rubra, on the South Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Apoptosis in the Shore ofO'ahu (Hawaiian Islands), 367-369 Symbiotic Light Organ of the Sepiolid Squid BIRKELAND, C. E.-see Green et al. Euprymna scolopes (abstract), liS BROCK, RICHARD E.-see Bailey-Brock et al. BROCK, RiCHARD, JULIE H. BAILEy-BROCK, and JOHN GARB, JESSICA E. GOODY Origins ofthe Hawaiian Crab Spider Fauna (abstract), A Case Study of Efficacy of Freshwater Immersion in 115-116 Controlling Introduction of Alien Marine Fouling GARRISON, JENNIFER Communities: The USS Missouri, 223-231 Role of Alien Tree Plantations in Native Forest BROCK, VERNON R.-see Bailey-Brock et al. -

Cultural Impact Assessment

Cultural Impact Assessment for the Honouliuli/Waipahu/Pearl City Wastewater Facilities, Honouliuli, Hō‘ae‘ae, Waikele, Waipi‘o, Waiawa, and Mānana, and Hālawa Ahupua‘a, ‘Ewa District, O‘ahu Island TMK: [1] 9-1, 9-2, 9-4, 9-5, 9-6, 9-7, 9-8, 9-9 (Various Plats and Parcels) Prepared for AECOM Pacific, Inc. Prepared by Brian Kawika Cruz, B.A., Constance R. O’Hare, B.A., David W. Shideler, M.A., and Hallett H. Hammatt, Ph.D. Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i, Inc Kailua, Hawai‘i (Job Code: HONOULIULI 35) April 2011 O‘ahu Office Maui Office P.O. Box 1114 16 S. Market Street, Suite 2N Kailua, Hawai‘i 96734 Wailuku, Hawai‘i 96793 www.culturalsurveys.com Ph.: (808) 262-9972 Ph: (808) 242-9882 Fax: (808) 262-4950 Fax: (808) 244-1994 Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 35 Prefatory Remarks on Language and Style Prefatory Remarks on Language and Style A Note about Hawaiian and other non-English Words: Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i (CSH) recognizes that the Hawaiian language is an official language of the State of Hawai‘i, it is important to daily life, and using it is essential to conveying a sense of place and identity. In consideration of a broad range of readers, CSH follows the conventional use of italics to identify and highlight all non-English (i.e., Hawaiian and foreign language) words in this report unless citing from a previous document that does not italicize them. CSH parenthetically translates or defines in the text the non-English words at first mention, and the commonly-used non-English words and their translations are also listed in the Glossary of Hawaiian Words (Appendix A) for reference. -

Reproduction and Development in Halocaridina Rubra Holthuis, 1963 (Crustacea: Atyidae) Clarifies Larval Ecology in the Hawaiian Anchialine Ecosystem

Reference: Biol. Bull. 229: 134–142. (October 2015) © 2015 Marine Biological Laboratory Reproduction and Development in Halocaridina rubra Holthuis, 1963 (Crustacea: Atyidae) Clarifies Larval Ecology in the Hawaiian Anchialine Ecosystem JUSTIN C. HAVIRD*,†, REBECCA C. VAUGHT, DAVID A. WEESE‡, AND SCOTT R. SANTOS Department of Biological Sciences and Molette Laboratory for Climate Change and Environmental Studies, Auburn University, 101 Rouse Life Sciences Bldg., Auburn, Alabama 36849 Abstract. Larvae in aquatic habitats often develop in and significantly higher in brackish and seawater (88% and environments different from those they inhabit as adults. 72%, respectively). Correlated with this finding, identifi- Shrimp in the Atyidae exemplify this trend, as larvae of able gills capable of ion transport did not develop until many species require salt or brackish water for develop- metamorphosis into juveniles. Thus, early life stages of ment, while adults are freshwater-adapted. An exception H. rubra are apparently excluded from surface waters, within the Atyidae family is the “anchialine clade,” which which are characterized by lower and fluctuating salini- are euryhaline as adults and endemic to habitats with sub- ties. Instead, these stages are restricted to the subterra- terranean fresh and marine water influences. Although the nean (where there is higher and more stable salinity) Hawaiian anchialine atyid Halocaridina rubra is a strong portion of Hawaii’s anchialine habitats due to their in- osmoregulator, its larvae have never been observed in na- ability to tolerate low salinities. Taken together, these ture. Moreover, larval development in anchialine species is data contribute to the understudied area of larval ecology poorly studied. Here, reproductive trends in laboratory col- in the anchialine ecosystem. -

Anchialine Shrimps in the Waikolao Area Has Been Constant, Except for Increases in ‘Ōpae ‘Ula Abundance Since 1996

Anchialine Ponds Anchialine Pond Shrimps Antecaridina lauensis Calliasmata pholidota ‘Ōpae ‘ula or Halocaridina rubra Halocaridina palahemo Metabetaeus lohena Procaris hawaiana Palaemonella burnsi Vetericaris chaceoru Metabetaeus lohena Courtesy Karl Magnacca SPECIES STATUS: All Federally Listed as Candidates except Halocaridina All State Listed as Candidates except Halocaridina IUCN Red List - Not considered All Endemic except Antecaridina, Calliasmata, Metabeteus SPECIES INFORMATION: This group of species live in underground (hypogeal) environments and in anchialine ponds which have a mix of freshwater and seawater through underground connections to the sea. All of the species except A. lauensis, C. pholidota, and M. lohena are endemic to Hawaii. ‘Ōpae ‘ula reaches 1.5 centimeters (one-half inch) in length and is an herbivore that grazes on algal, bacterial, and diatom films growing on rocks and other hard substrates. They can also filter feed in mid-water and at the surface. The other species are all larger (up to five cm or two inches long) and some are predatory. M. lohena is a snapping shrimp and feeds on ‘ōpae ‘ula. C. pholidota feeds on crustaceans and polychaetes, while P. hawaiana has been seen feeding on shrimp. All have red color and reduced appendages. ‘Ōpae ‘ula carry about 12 fertilized eggs under their abdomen for a brood period of about 38 days. They reproduce one to two times per year. Lifespan of ‘ōpae ‘ula is long, up to 20 years in captivity. Less is known about the life history of the other species, but they are relatively long- lived for species in their taxa. A. lauensis and M. lohena can live six years. -

Disturbance in the Anchialine Ecosystem: Ramifications for Ecology and Physiology

Disturbance in the anchialine ecosystem: ramifications for ecology and physiology by Justin Chase Havird A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama May 3, 2014 Keywords: ecophysiology, invasive species, crustacean, osmoregulation, gene expression Copyright 2014 by Justin Chase Havird Approved by Scott R Santos, Chair, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Raymond P. Henry, Professor of Biological Sciences Mark R. Liles, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Alan E. Wilson, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences/Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences Abstract Habitats in the anchialine ecosystem are defined as coastal ponds, pools, and caves that lack surface connections to the open ocean, but possess both seawater and freshwater influences due to subterranean connections to the ocean and groundwater. Such habitats are rare worldwide, but are concentrated in the Hawaiian Islands. Organisms that live in these habitats must cope with changing salinities, variable oxygen regimes, high levels of UV radiation, and anthropogenic effects such as pollution and invasive species. Accordingly, such organisms represent an opportunity to shed light on environmental physiology and invasive species biology. However, few studies have investigated physiology or response to invasive species in anchialine organisms. Accordingly, the objective of this dissertation is to examine the effect of natural and anthropogenic disturbances on the physiology and ecology of anchialine organisms. Chapter 1 provides an introduction to the anchialine ecosystem and outlines the specific aims of the dissertation. Chapter 2 presents a series of field and laboratory based experiments investigating how endemic Hawaiian anchialine organisms have responded to invasive fishes. -

Hoffman Dissertation.Pdf

Determining the spatial and seasonal influences of microbial community composition and structure from the Hawaiian anchialine ecosystem by Stephanie Kimie Hoffman A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 10, 2016 Keywords: anchialine, microbial ecology, Hawaii, laminated mat, spatial variation, seasonal variation Copyright 2016 by Stephanie Kimie Hoffman Approved by Scott R Santos, Chair, Professor of Biological Sciences Mark R Liles, Professor of Biological Sciences Todd D Steury, Associate Professor of Wildlife Sciences Robert S Boyd, Professor and Undergraduate Program Officer of Biological Sciences Abstract Characterized as coastal bodies of water lacking surface connections to the ocean but with subterranean connections to the ocean and groundwater, habitats belonging to the anchialine ecosystem occur worldwide in primarily tropical latitudes. Such habitats contain tidally fluctuating complex physical and chemical clines and great species richness and endemism. The Hawaiian Archipelago hosts the greatest concentration of anchialine habitats globally, and while the endemic atyid shrimp and keystone grazer Halocaridina rubra has been studied, little work has been conducted on the microbial communities forming the basis of this ecosystem’s food web. Thus, this dissertation seeks to fill the knowledge gap regarding the endemic microbial communities in the Hawaiian anchialine ecosystem, particularly regarding spatial and seasonal influences on community diversity, composition, and structure. Briefly, Chapter 1 introduces the anchialine ecosystem and specific aims of this dissertation. In Chapter 2, environmental factors driving diversity and spatial variation among Hawaiian anchialine microbial communities are explored. Specifically, each sampled habitat was influenced by a unique combination of environmental factors that correlated with correspondingly unique microbial communities. -

An Introduction to 'Opae 'Ula

Partnerships for Reform through Investigative Science and Mathematics An Introduction to ‘opae ‘ula ANCHIALINE Summary PONDS In this lesson, students learn the major body parts of ‘opae ‘ula (Halocaridina rubra) by observing a live specimen in the classroom. Concepts From their observation, students discuss in groups and learn the Students will focus on functions of each body part of the shrimp. an endemic animal that lives in anchialine Objectives ponds, the ‘opae’ula. • Students will construct habitat jars for ‘opae ‘ula. They will observe and • Students will identify and discover the functions for the describe the body, major body parts (structures) of ‘opae ‘ula. structure and function, • Students will observe ‘opae ‘ula behavior. and behavior of this animal through drawings and Materials (per pair of students) discussion. 1 large jar Five live ‘opae ‘ula (sold at local pet stores). HCPS III Benchmarks 1 magnifying glass or one digital microscope for the entire class SC.K.1.1 1 cup of sand SC.K.1.2 1 or 2 rocks covered in algae (you can find these in the intertidal SC.K.1.3 zone) For the entire class: Duration 1 enlarged figure of ‘opae ‘ula with body parts labeled (see below). 1 hour 1 piece of blank paper or science journal for each student. Source Material Making Connections PRISM We see shrimp almost every day. They are on our dinner tables, in Micro-lobster homepage our refrigerators, and on the food shelves at the grocery store. They Anchialine ponds are being sold in the seafood markets, farmer’s markets and detective story supermarkets. -

Inventory of Anchialine Pools in Hawai'i's National Parks

U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY and the NATIONAL PARK SERVICE - OUR VOLCANIC PUBLIC LANDS Inventory of Anchialine Pools in Hawai‘i’s National Parks Pools Harbor a Charismatic Fauna Many endemic and native shrimp species occur in anchia- line pools throughout the Hawaiian Islands, one of which is the small ‘oˉpae‘ula (Halocaridina rubra; Fig. 2). ‘Oˉpae‘ula naturally cover pool bottoms in a thick red carpet, feasting on pool algae. These shrimp can utilize underground cracks to travel between pools. They have few natural enemies, resulting in a high susceptibility to introduced predators such as fish and prawns. ‘Oˉpae‘ula are typically skittish and scarce, or absent all together in pools containing exotic fish. Like many other Hawaiian organisms, native shrimp species provide an interesting example of evolution by adaptive radia- tion. Among these species, some inhabit deeper areas of the pool, while some stay near surface waters. They also exploit different feeding strategies; while many feed on bacteria and algae, one species (Metabetaeus lohena; Fig. 3) has evolved to prey on other members of its evolutionary group, including ‘oˉpae‘ula. Several of these unique species are candidates for endangered species status. Figure 1. A large anchialine pool set back from the ocean along the Kona Coast: a place where fresh groundwater mixes with saltwater. (Photo © Greg Vaughn/www.GregVaughn.com) Background Anchialine (“near the sea”) pools are rare and localized brackish waters along coastal lava flows that exhibit tidal fluc- tuations without a surface connection with the ocean (Fig. 1). In Hawai‘i, these pools were frequently excavated or otherwise modified by Hawaiians to serve as sources of drinking water, baths and fish ponds. -

Caridean Shrimps Found In

CARIDEAN SHRIMPS FOUND IN LAND-LOCKED SALTWATER POOLS AT FOUR INDO-WEST PACIFIC LOCALITIES (SINAI PENINSULA, FUNAFUTI ATOLL, MAUI AND HAWAII ISLANDS), WITH THE DESCRIPTION OF ONE NEW GENUS AND FOUR NEW SPECIES by L. B. HOLTHUIS Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden With 13 text-figures and 7 plates At several occasions red coloured caridean shrimps have been reported from tropical land-locked saltwater pools. These pools are situated at some distance from the sea, but, because the level of the water rises and falls with the tides, must have subterranean connections with the sea. The shrimps belong to species that so far have not been found outside this special type of habitat, although some have a rather extensive geographical distribution. Apart from the peculiar habitat in which they are found and apart from their red coloration, there is very little that these species have in common. The 11 species so far found exclusively in these pools belong to 9 different genera and to 5 different families (see also Holthuis, 1963; Chace & Manning, 1972). It is suggested now to use the term "anchialine" (from the Greek anchialos, near the sea) to indicate this type of habitat, rather than to have to define it each time as "pools with no surface connection with the sea, containing salt or brackish water, which fluctuates with the tides". Recently, I received unusually interesting caridean material taken from several of such anchialine pools in the Indo-West Pacific region. This material was provided by various persons. In November 1971 and again in March 1972 Dr.