Torture, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment in Closed Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Central Regions and the Sofia Agglomeration Area

Maria Shishmanova THE CENTRAL REGIONS AND THE SOFIA AGGLOMERATION AREA Abstract. The research presents central regions in Bulgaria using taxonometric method with relevant conclusions. Each municipality in central regions is particularly examined by the elaborated methodic materials. The developed agglomeration areas are situated in the central regions. Sofia agglomeration area is presented using General Spatial Plan of Sofia municipality and Municipal Development Plan (MDP) of Sofia metropolitan municipality. It is set out the vision of development and its priorities, objectives and measures. Key words: central regions, agglomeration areas, Sofia agglomeration area, General Spatial Plan, Municipal Development Plan. Introduction The Central regions comprise 45 percent of the Bulgarian territory. The agglomeration areas are formed in them. The present study examines the development of the Sofia agglomeration area – a metropolis in the central regions of Bulgaria. The agglomeration areas are formed within the range of the central regions in Bulgaria – 6 agglomeration areas with a center – a large city, 30 agglomeration areas with a center – a medium-sized town. Six of the agglomeration areas are formations with more than three municipalities, five of them are with three municipalities each, ten are with 2 municipalities and the rest 15 are autonomous municipalities with an established core. These areas represent the backbone of the economy and social and human potential of the country. They have the highest degree of competitiveness and attractiveness for investment and innovation. Eighty eight municipalities with a total population of 5885455 people1 are included within the scope of the agglomeration areas, which constitutes 77.4 percent of the population of the country. -

Navigation Map of Bulgaria Including Offroadmap by Offroad-Bulgaria.Com Version 2021 Q1

Navigation Map of Bulgaria Including OFFRoadMap by OFFRoad-Bulgaria.com Version 2021 Q2 The purpose of this map is to provide accessible, accurate and up-to-date information for your GPS devices. Despite all efforts made by the creators to achieve this goal, the roads and the data included in this digital map are intended to be used as guidance only and should not be used solely for navigation. The creators of this map make no warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of the map data. In no event will the creators of this map be liable for any damages whatsoever, including but not limited to loss of revenue or profit, lost or damaged data, and expenses, arising in any way from or consequential upon the use of, or the inability to use this digital map. Contents: - Registering your map - Usage details - OFRM Geotrade 2021 Q2 variants - Coverage >>>>> REGISTRATION <<<<< To register your OFRM Geotrade map, please visit out website www.karta.bg. Click on “Create profile” in the top right corner of the screen and create your personal account. When done, the Support page will load automatically. Click on the button “Register OFRM Geotrade” and enter the 25-symbol map serial number and GPS model to activate your map’s update subscription (if your map includes one). To obtain the 25-symbol serial number, connect your GPS device to your computer via USB cable. If you have a GPS device with preloaded OFRM map, you will find the serial number in file “serial.txt” in the root folder of your device’s base memory or in the file “gmapsupp.unl” in folder “Garmin” (or folder “Map” on the newer models of the nüvi series and the new Drive series) of your device’s base memory. -

Dips Салати | Salads Супа | Soup Предястия | Appetizers

РАЗЯДКИ | DIPS g BGN Тиро 150 6.00 Tiro Хумус 150 6.00 Hummus Кьопоолу 150 6.00 Eggplant caviar Tарама хайвер 150 6.00 Tarama caviar САЛАТИ | SALADS Шопска 250 9.00 Shopska домати, краставици, сирене, tomatoes, cucumbers, white cheese, пресен пипер, лук, маслини peppers, onion, olives Дзадзики 250 8.00 Dzadziki цедено кисело мляко, strained yoghurt, cucumbers, краставици, мента, зехтин mint, olive oil Табуле 250 8.00 Tabbouleh булгур, магданоз, домат, bulgur, tomatoes, parsley, чесън, зехтин, лимон garlic, olive oil, lemon Печен пипер 250 9.00 Roasted peppers катък, чесън, зехтин garlic, cream cheese, olive oil СУПА | SOUP Рибена супа 250 7.00 Fish soup ПРЕДЯСТИЯ | APPETIZERS Запечено халуми с домат 150 10.00 Grilled Halloumi with tomatoes Хрупкави тиквички 200 7.00 Crispy zucchini Хрупкави калмари 200 9.00 Fried crispy calamari Миди с чили 300 10.00 Mussels with chili Пържен сафрид 200 11.00 Fried scad fish Пържен патладжан 250 9.00 Fried eggplant with с доматен сос и сирене фета tomato sauce and feta cheese Пържен свински дроб 200 8.00 Fried pork liver Патешки сърца 250 8.00 Fried duck hearts БАРБЕКЮ | BARBECUE g BGN Пилешко филе 250 12.00 Chicken fillet Свинска вратна пържола 250 15.00 Pork neck steak Свинско шишче 100 6.00 Pork skewer Пилешко шишче 100 6.00 Chicken skewer Телешки шиш кебап 250 16.00 Beef kebap Телешки карначета 200 12.00 Beef sausages Агнешки кюфтета 180 12.00 Lamb meat balls Адана кебап 200 14.00 Adana kebap Плескавица 250 13.00 Pleskavitsa Ястията, приготвени на барбекю, се сервират с гарнитура арабски булгур, запечен -

A Change in a Child Is a Change for Bulgaria Annual Report 2015

A CHANGE IN A CHILD IS A CHANGE FOR BULGARIA ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ABOUT NNC The National Network for Children (NNC) is an alliance of 131 civil society organisations and supporters, working with and for children and families across the whole country. Promotion, protection and observing the rights of the child are part of the key principles that unite us. We do believe that all policies and practices, that affect directly or indirectly children should be based first and foremost on the best interests of the child. Furthermore they should be planned, implemented and monitored with a clear assessment of the impact on children and young people, and with their active participation. OUR VISION The National Network for Children works towards a society where every child has their own family and enjoys the best opportunities for life and development. There is a harmony between the sectoral policies for the child and the family, and the child rights and welfare are guaranteed. OUR MISSION The National Network for Children advocates for the rights and welfare of children by bringing together and developing a wide, socially significant network of organisations and supporters. OUR GOALS • Influence for better policies for children and families; • Changing public attitudes to the rights of the child; • Development of a model for child participation; • Development of the National Network for Children; • Improving the capacity of the Network and its member organisations; • Promotion of the public image of the National Network for Children. II | Annual Report 2015 | www.nmd.bg Dear friends, In 2015 the National Network for Children made a big step forward and reached its 10th anniversary which we are celebrating today. -

Sofia Model”: Creation out of Chaos

The “Sofia Model”: Creation out of chaos Pathways to creative and knowledge-based regions ISBN 978-90-75246-62-9 Printed in the Netherlands by Xerox Service Center, Amsterdam Edition: 2007 Cartography lay-out and cover: Puikang Chan, AMIDSt, University of Amsterdam All publications in this series are published on the ACRE-website http://www2.fmg.uva.nl/acre and most are available on paper at: Dr. Olga Gritsai, ACRE project manager University of Amsterdam Amsterdam institute for Metropolitan and International Development Studies (AMIDSt) Department of Geography, Planning and International Development Studies Nieuwe Prinsengracht 130 NL-1018 VZ Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel. +31 20 525 4044 +31 23 528 2955 Fax +31 20 525 4051 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © Amsterdam institute for Metropolitan and International Development Studies (AMIDSt), University of Amsterdam 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced in any form, by print or photo print, microfilm or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. The “Sofia Model”: Creation out of chaos Pathways to creative and knowledge-based regions ACRE report 2.10 Evgenii Dainov Ivan Nachev Maria Pancheva Vasil Garnizov Accommodating Creative Knowledge – Competitiveness of European Metropolitan Regions within the Enlarged Union Amsterdam 2007 AMIDSt, University of Amsterdam ACRE ACRE is the acronym for the international research project Accommodating Creative Knowledge – Competitiveness of European Metropolitan Regions within the enlarged Union. The project is funded under the priority 7 ‘Citizens and Governance in a knowledge-based society within the Sixth Framework Programme of the EU (contract no. 028270). Coordination: Prof. -

Exchange of Experiences with Previous Replacement Campaigns and Their Embedding in Policy Programmes, SWOT of Facilitating Policy Measures

Exchange of experiences with previous replacement campaigns and their embedding in policy programmes, SWOT of facilitating policy measures Report D2.4 Project Coordinator: Austrian Energy Agency – AEA Work Package 2 Leader Organization: Jožef Stefan Institute May 2020 This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 847087. Authors Gašper Stegnar, Tadeja Janša, Boris Sučić, Marko Matkovič, JSI Tretter Herbert, Shruti Athavale, AEA Angel Nikolaev, BSERC Francisco Puente, Margarita Puente, ESCAN Velimir Šegon, Iva Tustanovski, REGEA Dražen Balić, EIHP Stefan Drexlmeier, EWO Ingo Ball, Benedetta di Constanzo, Dominik Rutz, WIP Slobodan Jerotić, City of Šabac Samra Arnaut, ENOVA Ricardo González, Rafael Ayuste, EREN Emilija Mihajloska, Vladimir Gjorgievski, Natasha Markovska, Ljupcho Dimov, Dimitar Grombanosvki, Sasha Maksimovski, SDEWES Skopje Project coordination and editing provided by Austrian Energy Agency. Manuscript completed in May 2020. This document is available on: www.replace-project.eu Document title Exchange of experiences with previous replacement campaigns and their embedding in policy programmes, SWOT of facilitating policy measures Work Package WP2 Document Type Deliverable Date 31.5.2020 Document Status Final version Acknowledgments & Disclaimer This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 847087. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. The views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission. Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. -

Ic-92 Seismic Estimation for Sofia Region with Neural

Joint International Conference on Computing and Decision Making in Civil and Building Engineering June 14-16, 2006 - Montréal, Canada SEISMIC ESTIMATION FOR SOFIA REGION WITH NEURAL MODELING Svetla Radeva1, Raimar J. Scherer2, Ivanka Paskaleva3 and Dimitar Radev4 ABSTRACT A study of the site effects and the microzonation of Sofia region, based on the modeling of seismic ground motion along three cross sections were carried out. Realistic synthetic strong motion waveforms have been computed for an earthquake scenario applying a hybrid modeling method, based on the modal summation technique, finite differences scheme and neural modeling. Realistic synthetic seismic signals have been generated for all sites of interest. Two groups of experiments have been performed, where in first group the ground motion is modeled for one-dimensional layered anelastic media, applying an algorithm based on the modal summation method. In second group of experiments the ground motion is modeled for two-dimensional laterally heterogeneous media and with implementation of neural network, learned and trained with real earthquake seismic records. The aim of suggested deterministic modeling is to provide site response estimates at Sofia due to the chosen earthquake scenarios and to show how to use the database of synthetic seismic signals, seismological and seismic engineering parameters. Modeling of site response for selected area on different distances from possible epicenter with synthetic time histories and neural networks will help to include developed models in structural control of important and high-risk structures. KEY WORDS earthquake engineering, stochastic modeling, seismic waves, neural networks. INTRODUCTION One of the very promising methods in earthquake engineering is application of structural control. -

MEDIANE Media in Europe for Diversity Inclusiveness

MEDIANE Media in Europe for Diversity Inclusiveness EUROPEAN EXCHANGES OF MEDIA PRACTICES EEMPS Pair: COE 73 OUTPUT BEING A FOREIGNER DOING BUSINESS SUMMARY 1. Exchange Partners Partner 1 Partner 2 Name and Surname Valentin TODOROV Meryem MAKTOUM Job title Managing Editor Freelance Organisation / Media Novi Iskar online Prospettive Altre 2. Summary Our common article ‘Being a foreigner doing business in Bulgaria - mission possible. How is it in Calabria - the southern Italian region?’, is a journalistic attempt to look at the conditions for doing business in Bulgaria and in Region of Calabria (Italy) through the eyes of several businessmen (with an origin of different countries in the world) who are established their small businesses in these two areas - known as of two of the poorest regions in Europe. The approach we chose with my Italian colleague Meriem Maktoum from Italian online media ‘Prospettive Altre’ was to work on the spot - in Bulgarian capital city Sofia and in the Italian town of Lamezia Terme (in Calabria, Italy), and to meet with local businessmen who describe the similar difficulties and advantages of doing business in Bulgaria and in the southern Italian region of Calabria. Our reportage presents different standpoints and positions of businessmen of foreign origin, who telling in the blitz interviews for our duo about their personal experiences in Bulgaria and Calabria, as our interlocutors share their opinions for their work, but also a positive experience doing small business in countries that have become their second home. The article, besides the economic differences between this two EU countries, presents the common human problems that excite these entrepreneurs and the things that are similar between them, and describes how these people are integrated into two different European countries - Italy and Bulgaria. -

2013 FAI EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS for SPACE MODELS Seniors and Juniors 24Th – 30Th August, 2013 – Kaspichan, Bulgaria

2013 FAI EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS for SPACE MODELS Seniors and Juniors 24th – 30th August, 2013 – Kaspichan, Bulgaria BULLETIN № 1 15 th December 2012 Kaspichan 2013 FAI EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS for SPACE MODELS Seniors and Juniors 24-30 august, Kaspichan Bulgaria ORGANIZERS: By appointment of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) Organizers are: National Aero Club of Bulgaria Bulgarian Aeromodelling Federation Municipality of Kaspichan Space model Club “Modelist”, Kaspichan Director of the Championships: Mr. Stanev Plamen Sports Director: Mr. Dimitrov Dimitar IT Service Manager: Mr. Yordanov Borislav Secretary of the Championships: Mrs. Stoyanova Sasha DESCRIPTION OF THE CHAMPIONSHIPS’ LOCATION: 2 Transportation: The European Championship shall be held in the municipality Kaspichan. Kaspichan is 20 km from the town of Shumen, where shall be registration and accommodation. Shumen is situated on the main road Sofia - Varna. Distance from Sofia to Shumen is 360 km, Varna - Shumen is 94 km and Varna - Ruse (125). The nearest international airports are in Varna (94 km), Burgas (155 km) and Sofia (360 km). The organizers offer transportation of participants from Varna, Burgas and Ruse at reasonable costs. Weather conditions: – average daily temperature: +16° - +35° C – average wind speed: 2 – 6 m / s – rainfall / month: 1 – 2 l / m2 SCHEDULE: Classes: Seniors S1B, S3A, S4A, S5C, S6A, S7, S8E/P, S9A Juniors S1A, S3A, S4A, S5B, S6A, S7, S8D, S9A № Data Competition Schedule Seniors Juniors Fly-offs Start – end Day Seniors Juniors Arrival -

A Case Study on Niğbolu Sandjak (1479-1483)

DEMOGRAPHIC STRUCTURE AND SETTLEMENT PATTERNS OF NORTH-EASTERN BULGARIA: A CASE STUDY ON NİĞBOLU SANDJAK (1479-1483) A Master’s Thesis By NURAY OCAKLI DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA JULY 2006 DEMOGRAPHIC STRUCTURE AND SETTLEMENT PATTERNS OF NORTH-EASTERN BULGARIA: A CASE STUDY ON NİĞBOLU SANDJAK (1479-1483) The Institute of Economic and Social Sciences of Bilkent University By NURAY OCAKLI In Partial Fullfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA July 2006 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. Prof. Dr. Halil İnalcık Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. Asst. Prof. Dr. Evgeny Radushev Examining Comitee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. Asst. Prof. Dr. Hasan Ünal Examining Comitee Member Approval of the Institute of Economic and Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT DEMOGRAPHIC STRUCTURE AND SETTLEMENT PATTERNS OF NORTH-EASTERN BULGARIA: A CASE STUDY ON NİĞBOLU SANDJAK (1479-1483) Nuray Ocaklı M.A., Department of History Supervisor: Halil İnalcık June 2006 This thesis examines demographic structure and settlement patterns of Niğbolu Sandjak in the the last two decades of the fifteenth century. -

Nominalia of the Bulgarian Rulers an Essay by Ilia Curto Pelle

Nominalia of the Bulgarian rulers An essay by Ilia Curto Pelle Bulgaria is a country with a rich history, spanning over a millennium and a half. However, most Bulgarians are unaware of their origins. To be honest, the quantity of information involved can be overwhelming, but once someone becomes invested in it, he or she can witness a tale of the rise and fall, steppe khans and Christian emperors, saints and murderers of the three Bulgarian Empires. As delving deep in the history of Bulgaria would take volumes upon volumes of work, in this essay I have tried simply to create a list of all Bulgarian rulers we know about by using different sources. So, let’s get to it. Despite there being many theories for the origin of the Bulgars, the only one that can show a historical document supporting it is the Hunnic one. This document is the Nominalia of the Bulgarian khans, dating back to the 8th or 9th century, which mentions Avitohol/Attila the Hun as the first Bulgarian khan. However, it is not clear when the Bulgars first joined the Hunnic Empire. It is for this reason that all the Hunnic rulers we know about will also be included in this list as khans of the Bulgars. The rulers of the Bulgars and Bulgaria carry the titles of khan, knyaz, emir, elteber, president, and tsar. This list recognizes as rulers those people, who were either crowned as any of the above, were declared as such by the people, despite not having an official coronation, or had any possession of historical Bulgarian lands (in modern day Bulgaria, southern Romania, Serbia, Albania, Macedonia, and northern Greece), while being of royal descent or a part of the royal family. -

DC 20 MENU ENG 2010 31.Cdr

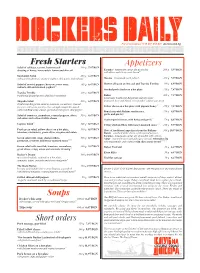

For reservations +359 887 005 007 dockersclub.bg Fresh Starters Appetizers Salad of cabbage, carrots, beetroot and 300 g 5,97 BGN dressing of honey, horseradish, lemon and olive oil Tarama - homemade caviar dip of sea fish 200 g 5,97 BGN with olives and slices rustic bread1,4 Snezhanka Salad 250 g 6,47 BGN with pickled gherkins, strained yoghurt, dill, garlic and walnuts7,8 Slanina - homemade pork fatback 100 g 5,97 BGN Salad of roasted peppers, beetroot, sweet corn, 180 g 6,47 BGN Skewer of bacon on live coal and Tsarska Тurshia 180 g 6,97 BGN walnuts, dill and strained yoghurt7,8 Smoked pork cheeks on a hot plate 150 g 7,47 BGN Tsarska Тurshia 200 g 6,47 BGN traditional Bulgarian mix of pickled vegetables Bahur 200 g 7,47 BGN homemade traditional Bulgarian sausage made Shopska Salad 300 g 6,97 BGN from pork liver and blood, served either cold or pan-fried Traditional Bulgarian salad of tomatoes, cucumbers, roasted 1,7 peppers, red onion, parsley, olive oil and vinaigrette, mixed Yellow cheese on a hot plate with piquant honey 150 g 7,47 BGN with crumbled white cheese, garnished with green chili pepper7 Bruschetta with Boletus mushrooms, 150 g 8,97 BGN 1,7 Salad of tomatoes, cucumbers, roasted peppers, olives, 350 g 8,47 BGN garlic and parsley 7 red onion and a slice of white cheese 7 Veal tongue in butter, with herbs and garlic 120 g 8,97 BGN 7,8 Caprese Salad 300 g 8,97 BGN Crispy chicken fillets with honey-mustard sauce1,3,10 220 g 9,97 BGN Fresh green salad, yellow cheese on a hot plate, 300 g 8,97 BGN 7 Plate of traditional appetizers