A Collaborative Self-Study Involving Choral Music Educators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

SKIVLISTA 4-2016 Hello Music Lovers! - Pay by Credit Card Through Paypal! Adress: Ange Min Email [email protected] Som Referens Vid Betalning

SKIVLISTA 4-2016 Hello music lovers! - pay by credit card through PayPal! Adress: www.paypal.com Ange min email [email protected] som referens vid betalning. Det har varit mycket ett tag nu. Men här kommer i alla fall en sommarlista, denna gång med enbart fastprisskivor. I sedvanlig ordning lämnar jag en sommarrabatt enligt följande: Därmed över till skivhögarna och GOOD HUNTING! LATE ADDITIONS 10% rabatt vid köp för 300-499 kronor 20% rabatt vid köp för 500-999 kronor SINGLES AND EPS 30% rabatt vid köp för 1 000 kronor och uppåt EPX ANDREWS SISTERS "In HiFi part 1" Bei mir bist Du schön/Beer barrel polka/Well all right!/Ferry boat serenade 1957, sobc (NO Capitol) VG+ 75:- Exempel: om du handlar för 665 kronor så avgår en rabatt på 133 kronor och du betalar alltså bara 532 kronor plus EPX BOBBY ANGELO Talk/Taste of the blues/Staying up late/Broken dreams 1964, red vinyl, great porto. Observera att detta gäller levererade skivor så v g ange alternativ vid beställning. Fraktfritt om slutsumman Sweden-only EP (SW Sonet) VG+ 250:- efter avdragen rabatt överstiger 1 000 kronor. Ovanstående rabatter avser fastprisskivor. X BOBBY BARE Miller's cave/Jeannie's last kiss 1964, NC (GE RCA Victor) VG+ 75:- EPX ARNE BILLS ORKESTER Trollebotwist/Twilight time/En visa vill jag sjunga/Per Speleman 1963, Det är inte ofta några kullar med pyrenéervalpar föds i Sverige. Men Frida föddes bara några veckor efter att min green vinyl, 2 instr., 2 vocals. Bra och efterfrågad EP. (SW Gazell) VG+ 180:- vän Ona gått bort. -

Qatar Airways, and Reem Al Mansoori, Assistant Undersecretary of Digital Post

BUSINESS | 01 SPORT | 08 Al Kuwari highlights QSL: Al Duhail significance go top with of Qatar-Turkey crushing win trade relations over Al Sadd Sunday 3 November 2019 | 6 Rabia I 1441 www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 24 | Number 8064 | 2 Riyals New phase of ‘Better Connections’ launched THE PENINSULA Prime Minister and programme aims to create 1,000 DOHA Interior Minister H E new electronic content to be made available through Prime Minister and Interior Sheikh Abdullah bin Hukoomi website for workers in Minister H E Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser bin Khalifa Al the five most widely used lan- Nasser bin Khalifa Al Thani has Thani has inaugurated guages among workers in Qatar, inaugurated the sustainability and the new phase of the suitable with the needs of expa- development phase of the “Better triate labour and the devel- Connections” programme, which “Better Connections” opment of the country. aims to employ expatriates and programme, which The Better Connections, enables them to use ICT devices aims to employ launched as a pilot project in 2013 to ensure their digital inclusion expatriates and and officially launched in 2015, is and improve their lifestyle. a national initiative launched by The launch took place on the enables them to use the Ministry of Transport and Com- sidelines of the Qatar Infor- ICT devices to ensure munications in collaboration with mation Technology and Commu- their digital inclusion. the Ministry of Administrative nication Conference and Exhi- Development, Labour and Social bition (QITCOM 2019), which Affairs, aiming to achieve digital concluded on Friday. The new phase of the program inclusion of expatriate workers in During the inauguration, which comes for a period of three years, Qatar by giving them free access Foreign Minister meets US Treasury Secretary was attended by Minister of during which technical support is to the network. -

Building Hope: Refugee Learner Narratives

Building Hope: Refugee Learner Narratives Manitoba Education and Advanced Learning © UNHCR/Zs. Puskas. June 19, 2012. World Refugee Day 2012 in Central Europe. Európa Pont venue of the European Commission in Budapest hosted an exhibition of drawings showing the response of school children to hearing refugee stories. 2015 <www.flickr.com/photos/unhcrce/7414749518/in/set-72157630205373344/>. Used with permission. All rights reserved. Manitoba Education and Advanced Learning Cataloguing in Publication Data Building hope [electronic resource] : refugee learner narratives Includes bibliographical references. ISBN: 978-0-7711-6067-7 1. Refugee children—Manitoba—Interviews. 2. Refugees—Manitoba—Interviews. 3. War victims—Manitoba—Interviews. 4. Refugee children—Education—Manitoba. 5. Refugees—Education—Manitoba. 6. War victims—Education—Manitoba. I. Manitoba. Manitoba Education and Advanced Learning. 371.826914 Copyright © 2015, the Government of Manitoba, represented by the Minister of Education and Advanced Learning. Manitoba Education and Advanced Learning School Programs Division Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Every effort has been made to acknowledge original sources and to comply with copyright law. If cases are identified where this has not been done, please notify Manitoba Education and Advanced Learning. Errors or omissions will be corrected in a future edition. Sincere thanks to the authors, artists, and publishers who allowed their original material to be used. All images found in this document are copyright protected and should not be extracted, accessed, or reproduced for any purpose other than for their intended educational use in this document. Any websites referenced in this document are subject to change. Educators are advised to preview and evaluate websites and online resources before recommending them for student use. -

View/Download Concert Program

Christmas in Medieval England Saturday, December 19, 2009 at 8 pm First Church in Cambridge, Congregational Christmas in Medieval England Saturday, December 19, 2009 at 8 pm First Church in Cambridge, Congregational I. Advent Veni, veni, Emanuel | ac & men hymn, 13th-century French? II. Annunciation Angelus ad virginem | dt bpe 13th-century monophonic song, Arundel MS / text by Philippe the Chancellor? (d. 1236) Gabriel fram Heven-King | pd ss bpe Cotton fragments (14th century) Gaude virgo salutata / Gaude virgo singularis isorhythmic motet for Annunciation John Dunstaple (d. 1453) Hayl, Mary, ful of grace Trinity roll (early 15th century) Gloria (Old Hall MS, no. 21) | jm ms ss gb pg Leonel Power (d. 1445) Ther is no rose of swych vertu | dt mb pg bpe Trinity roll Ibo michi ad montem mirre | gp jm ms Power III. Christmas Eve Veni redemptor gencium hymn for first Vespers of the Nativity on Christmas Eve, Sarum plainchant text by St Ambrose (c. 340-97) intermission IV. Christmas Dominus dixit ad me Introit for the Mass at Cock-Crow on Christmas Day, Sarum plainchant Nowel: Owt of your slepe aryse | dt pd gp Selden MS (15th century) Gloria (Old Hall MS, no. 27) | mn gp pd / jm ss / mb ms Blue Heron Pycard (?fl. 1410-20) Pamela Dellal | pd ss mb bpe Ecce, quod natura Martin Near Selden MS Gerrod Pagenkopf Missa Veterem hominem: Sanctus Daniela Tošić anonymous English, c. 1440 Ave rex angelorum | mn mb ac Michael Barrett Egerton MS (15th century) Allen Combs Jason McStoots Missa Veterem hominem: Agnus dei Steven Soph Nowel syng we bothe al and som Mark Sprinkle Trinity roll Glenn Billingsley Paul Guttry Barbara Poeschl-Edrich, Gothic harp Scott Metcalfe,director Pre-concert talk by Daniel Donoghue, Professor of English, Harvard University sponsored by the Cambridge Society for Early Music Blue Heron Renaissance Choir, Inc. -

Summary Announcement

Evropski centar European Center za mir i razvoj for Peace and Development Terazije 41 Centre Européen 11000 Beograd, Serbia pour la Paix et le Développement Centro Europeo ECPD Headquarters para la Paz y el Desarrollo Европейский центр мира и развития University for Peace established by the United Nations ECPD International Conference FUTURE OF THE WORLD BETWEEN GLOBALIZATION AND REGIONALIZATION (Belgrade, City Hall, 28-29 October 2016) POST CONFERENCE SUMMARY ANNOUNCEMENT The XII ECPD International Conference examined pathways between Regionalization and Globalization as determinants for the future of the world. The asked what stands in the way of integration, whether we can simultaneously think globally and think regionally and what are the strengths and weakness in the inherent processes and present outcomes over the many domains of society (which approaches to the challenges involved could be most effective for all parts of society) and in all parts of the world. In continuation, the Balkan world received a check up and (and the pressures affecting the region were assessed and global pulse was measured. Tensions between the Russian Federation and the United States of America, migration resulting from armed conflict and poverty in the Middle East, tensions within the European Union after the UK Brexit vote, and the new strategic paradigm of macro-regionalization were high on the agenda. The role of China was agreed to be of key importance in the global system. A number of presentations / additional discussion covered the ongoing global socio-economic crisis and a description of potentially accelerating global catastrophe; the survival of humanity and man’s future together with its rough edges and the paradoxes of life; our responsibility as a precondition for peace, the new Cold War and allocation of guilt; migration as an exceedingly complex problem, peace in the Middle East and the lack of Global Governance. -

Cat Empire Live Dvd

Cat empire live dvd click here to download You asked for it! The Cat Empire have played over incredible shows around the world. Finally, they're. Sly - The Cat Empire Live on David Letterman · Steal The Light - WOMADelaide · Steal The Light - Behind The Scenes · Brighter Than Gold - Behind The Scenes · Days Like These, Live at Stage 88, Commonwealth Park · 'Introducing' from the On The Attack DVD · The Car Song, Live at the Forum from the Two Shoes. Live On Earth, double live album The Latest release from THE CAT EMPIRE. This Live double-album features 22 live recordings, from shows recorded all over the world. Melbourne, Montreal, Paris, London, New York and more this is the closest you can come to having The Cat Empire live in your lounge room. Recorded. We had a great thing going for a long time multiple shows in a row at the Shepherd's Bush Empire in London. This one was recorded in Wolves and All Night Loud - New videos LIVE from The Forum Theatre Read More This week's Bacstage Pass is two clips from our early DVD relese, On The Attack. The Lost Song. Find a The Cat Empire - Live At The Bowl first pressing or reissue. Complete your The Cat Empire collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Find a The Cat Empire - Live On Earth Sampler first pressing or reissue. Complete Since The Cat Empire began in , our fans have been begging us to release some of our live recordings. This year Feb 28 is the release date for both the double album, LIVE ON EARTH and the DVD, LIVE AT THE BOWL. -

The Religious Landscape in South Sudan CHALLENGES and OPPORTUNITIES for ENGAGEMENT by Jacqueline Wilson

The Religious Landscape in South Sudan CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR ENGAGEMENT By Jacqueline Wilson NO. 148 | JUNE 2019 Making Peace Possible NO. 148 | JUNE 2019 ABOUT THE REPORT This report showcases religious actors and institutions in South Sudan, highlights chal- lenges impeding their peace work, and provides recommendations for policymakers RELIGION and practitioners to better engage with religious actors for peace in South Sudan. The report was sponsored by the Religion and Inclusive Societies program at USIP. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jacqueline Wilson has worked on Sudan and South Sudan since 2002, as a military reserv- ist supporting the Comprehensive Peace Agreement process, as a peacebuilding trainer and practitioner for the US Institute of Peace from 2004 to 2015, and as a Georgetown University scholar. She thanks USIP’s Africa and Religion and Inclusive Societies teams, Matthew Pritchard, Palwasha Kakar, and Ann Wainscott for their support on this project. Cover photo: South Sudanese gather following Christmas services at Kator Cathedral in Juba. (Photo by Benedicte Desrus/Alamy Stock Photo) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2019 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. 148. First published 2019. -

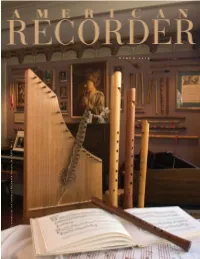

M a R C H 2 0

march 2005 Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. XLVI, No. 2 XLVI, Vol. American Recorder Society, by the Published Order your recorder discs through the ARS CD Club! The ARS CD Club makes hard-to-find or limited release CDs by ARS members available to ARS members at the special price listed (non-members slightly higher). Add Shipping and Handling:: $2 for one CD, $1 for each additional CD. An updated listing of all available CDs may be found at the ARS web site: <www.americanrecorder.org>. NEW LISTING! ____THE GREAT MR. HANDEL Carolina Baroque, ____LUDWIG SENFL Farallon Recorder Quartet Dale Higbee, recorders. Sacred and secular music featuring Letitia Berlin, Frances Blaker, Louise by Handel. Live recording. $15 ARS/$17 Others. ____HANDEL: THE ITALIAN YEARS Elissa Carslake and Hanneke van Proosdij. 23 lieder, ____SOLO, Berardi, recorder & Baroque flute; Philomel motets and instrumental works of the German DOUBLE & Baroque Orchestra. Handel, Nel dolce dell’oblio & Renaissance composer. TRIPLE CONCER- Tra le fiamme, two important pieces for obbligato TOS OF BACH & TELEMANN recorder & soprano; Telemann, Trio in F; Vivaldi, IN STOCK (Partial listing) Carolina Baroque, Dale Higbee, recorders. All’ombra di sospetto. Dorian. $15 ARS/$17 Others. ____ARCHIPELAGO Alison Melville, recorder & 2-CD set, recorded live. $24 ARS/$28 others. traverso. Sonatas & concerti by Hotteterre, Stanley, ____JOURNEY Wood’N’Flutes, Vicki Boeckman, ____SONGS IN THE GROUND Cléa Galhano, Bach, Boismortier and others. $15 ARS/$17 Others. Gertie Johnsson & Pia Brinch Jensen, recorders. recorder, Vivian Montgomery, harpsichord. Songs ____ARLECCHINO: SONATAS AND BALLETTI Works by Dufay, Machaut, Henry VIII, Mogens based on grounds by Pandolfi, Belanzanni, Vitali, OF J. -

Den Svenska Musikskatten Visor- 1800 Och 1900-Tal

Den svenska musikskatten Visor- 1800 och 1900-tal Carl-Mikael Bellman Cornelis Vreeswijk Dansband Folkmusik, folkvisor, spelmansmu- Carl-Mikael Bellman (1740-1795) sik Fjäril vingad syns på Haga, Åsa Jinder Fosterländska toner https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=6NZZKA6cXfA&frags=pl%2Cwn Gamla örhängen och stenkakor Värm mer öl och bröd, Fred Åkerström (1920 - 1960) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZnEluhTSiI Jazz Glimmande nymf, Fred Åkerström Klassisk musik http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5bUlCRpTs3o Låtar- från 70-talet Ulla, min Ulla, Cornelis Vreeswijk Låtar från 80-talet http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=97zu8dZqa5w Så lunka vi så småningom, Fred Åkerström Låtar från 90-talet https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m0jwCyudYfA Låtar från 00-talet Nå skruva fiolen, Fred Åkerström Låtar från 10-talet https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=P9Y5Uf1RoEw&frags=pl%2Cwn Melodifestivalen Vila vid denna källa, Fred Åkerström Pre-Abba https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pbp26wfjpV0 Proggen Ack du min moder, Fred Åkerström Psalmer, andliga sånger https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j_8JCTSdLIc Märk hur vår skugga, Imperiet På engelska (artistlista) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ssqmu-MYw- Rapp/ Hipp hopp BQ&frags=pl%2Cwn Gråt fader Berg, Merit Hemmingsson, Bengan Revy, kabaré och musikal Karlsson Samisk musik https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g44DOt- S66ww&frags=pl%2Cwn Schlagerdrottningar Fredmans epistel no 44, Mikael Samuelsson, Svenska körklassiker Garmarna, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gw1Im1yW- Evert Taube tUo&frags=pl%2Cwn Bellmans vaggvisa, Lena Willemark Här -

Winter 2009 Volume 24 No

MAGAZINE ™ Hope & Healing for the Body, Mind & Spirit Winter 2009 Volume 24 No. 4 www.livingwithloss.com Bereavement Publications, Inc. Gifts from the Hope and Healing Cards New! Pet Loss Card Outside copy: How does one say goodbye to a beloved pet? for the Holidays Inside copy: The ache in our hearts When a companion-animal friend dies Is difficult to put into words, But there is comfort in remembering Unique ideas for your holiday bereavement The special moments that were shared, The honesty of that friendship program, memorial service, candle lighting And the unique place this beloved animal ceremony or just to say “thinking of you”. Will always have in our affections. Thinking of you at this time 1201 of difficult loss. SEE PAGE 44 1. Outside copy: On the anniversary 2. Outside copy: Saying Goodbye of your loved one’s death… Inside copy: Holiday Inside copy: May you treasure the ...is perhaps the hardest thing unforgettable moments and you’ve had to do... meaningful words you shared, May hope rise like the dawn- Bear Care May you find comfort, To give you strength in each new day. Santa's Precious Helpers Bring hope, and peace in each new day, Hope and Cheer And may your journey lead you 1210 to a new place of healing. 1215 3. NEW!! 4. Outside copy: You’ve shared Outside copy: your loved one’s final journey Remembering Your Loved One and said a last goodbye… Inside copy: Inside copy: May your pain soften Today and Always. and fade As treasured memories bring the peace That will brighten the days ahead. -

Music for Guitar

So Long Marianne Leonard Cohen A Bm Come over to the window, my little darling D A Your letters they all say that you're beside me now I'd like to try to read your palm then why do I feel so alone G D I'm standing on a ledge and your fine spider web I used to think I was some sort of gypsy boy is fastening my ankle to a stone F#m E E4 E E7 before I let you take me home [Chorus] For now I need your hidden love A I'm cold as a new razor blade Now so long, Marianne, You left when I told you I was curious F#m I never said that I was brave It's time that we began E E4 E E7 [Chorus] to laugh and cry E E4 E E7 Oh, you are really such a pretty one and cry and laugh I see you've gone and changed your name again A A4 A And just when I climbed this whole mountainside about it all again to wash my eyelids in the rain [Chorus] Well you know that I love to live with you but you make me forget so very much Oh, your eyes, well, I forget your eyes I forget to pray for the angels your body's at home in every sea and then the angels forget to pray for us How come you gave away your news to everyone that you said was a secret to me [Chorus] We met when we were almost young deep in the green lilac park You held on to me like I was a crucifix as we went kneeling through the dark [Chorus] Stronger Kelly Clarkson Intro: Em C G D Em C G D Em C You heard that I was starting over with someone new You know the bed feels warmer Em C G D G D But told you I was moving on over you Sleeping here alone Em Em C You didn't think that I'd come back You know I dream in colour