Where None Have Gone Before: Operational

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

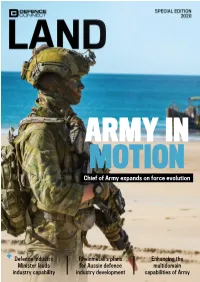

Chief of Army Expands on Force Evolution

ARMY IN MOTION Chief of Army expands on force evolution + Defence Industry Rheinmetall’s plans Enhancing the Minister lauds for Aussie defence multidomain industry capability industry development capabilities of Army Welcome EDITOR’S LETTER Army has always been the nation’s first responder. Recognising this, government has moved to modernise the force and keep it at the cutting-edge of capability Shifting gears, Rheinmetall Defence Australia provides a detailed look into their extensive research and development programs across unmanned systems, and collaborative efforts to Steve Kuper develop critical local defence industry capability. Analyst and editor Local success story EPE Protection discusses Defence Connect its own R&D and local industry and workforce development efforts, building on its veteran- focused experience in the land domain. WHILE BOTH Navy and Air Force are Luminact discusses the importance of well progressed on their modernisation information supremacy and its role in and recapitalisation programs, driven by supporting interoperability. The company also platforms like the F-35 Joint Strike Fighters discusses how despite platform commonality, and Hobart Class destroyers, Army is at the interoperability can’t be guaranteed and needs beginning of this process. Following on from to be accounted for. the success of the Defence Connect Maritime HENSOLDT Australia chats about its growing & Undersea Warfare Special Edition, this footprint across the ADF, with expertise second edition focused on the Land Domain learned during the company’s relationship with will deep-dive into the programs, platforms, Navy and Air Force to build a diverse offering, capabilities and doctrines emerging that will enhancing Army’s survivability and lethality. -

2020 Yearbook

-2020- CONTENTS 03. 12. Chair’s Message 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 2 & Tier 3 04. 13. 2020 Inductees Vale 06. 14. 2020 Legend of Australian Sport Sport Australia Hall of Fame Legends 08. 15. The Don Award 2020 Sport Australia Hall of Fame Members 10. 16. 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 1 Partner & Sponsors 04. 06. 08. 10. Picture credits: ASBK, Delly Carr/Swimming Australia, European Judo Union, FIBA, Getty Images, Golf Australia, Jon Hewson, Jordan Riddle Photography, Rugby Australia, OIS, OWIA Hocking, Rowing Australia, Sean Harlen, Sean McParland, SportsPics CHAIR’S MESSAGE 2020 has been a year like no other. of Australian Sport. Again, we pivoted and The bushfires and COVID-19 have been major delivered a virtual event. disrupters and I’m proud of the way our team has been able to adapt to new and challenging Our Scholarship & Mentoring Program has working conditions. expanded from five to 32 Scholarships. Six Tier 1 recipients have been aligned with a Most impressive was their ability to transition Member as their Mentor and I recognise these our Induction and Awards Program to prime inspirational partnerships. Ten Tier 2 recipients time, free-to-air television. The 2020 SAHOF and 16 Tier 3 recipients make this program one Program aired nationally on 7mate reaching of the finest in the land. over 136,000 viewers. Although we could not celebrate in person, the Seven Network The Melbourne Cricket Club is to be assembled a treasure trove of Australian congratulated on the award-winning Australian sporting greatness. Sports Museum. Our new SAHOF exhibition is outstanding and I encourage all Members and There is no greater roll call of Australian sport Australian sports fans to make sure they visit stars than the Sport Australia Hall of Fame. -

The Australian Defence, Police and Emergency

THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE, POLICE AND EMERGENCY SERVICES LEADERSHIP SUMMIT 2015 ASSOCIATION MEMBER RATES Developing Today’s Managers LIMITED SEATS for Leadership Excellence AVAILABLE PREVIOUS SUMMIT SPEAKERS INCLUDE: David Melville APM David Irvine Lieutenant General Tony Negus APM Rear Admiral D.R. Air Marshal Ken D. Lay APM Warren J. Riley Former Commissioner, Former Director General David Morrison AO Former Commissioner Thomas AO, CSC, RAN Mark Binskin AO Former Chief Commissioner, Former Superintendent, QLD Ambulance Service of Security ASIO Chief of Army Australian Federal Police Former Deputy Former Vice Chief of the Victoria Police New Orleans Chief of Navy Defence Force (VCDF) Police Department The Australian Defence, Police and Emergency Services Leadership Summit 2015 will be held in Melbourne on Thursday 25th and Friday 26th June. In its sixth year, this HOST CITY significant national program drawing together the sectors most respected thought leaders with the aim to equip managers/leaders with the skills to adapt and respond ef- fectively, particularly in highly pressurised or extreme situ- PARK HYATT, MELBOURNE ations where effective leadership saves lives. 25TH & 26TH JUNE PRESENTING ORGANISATIONS FROM THE 2012, 2013 & 2014 SUMMITS INCLUDE: Australian Government Department of Defence THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE, POLICE AND EMERGENCY SERVICES LEADERSHIP SUMMIT 2015 OVERVIEW Including presentations from an esteemed line-up of high ranking officers and officials, as well as frontline and operational people managers, the Summit offers an unparalleled opportunity to observe effective individual and organisational leadership inside of Australia’s Defence, Police and Emergency Services. In addition to providing a platform to explore contemporary leadership practice, the Summit provides a unique opportunity for delegates to develop invaluable professional and personal networks. -

Kemp - DHAAT 05 (28 May 2021)

Hulse and the Department of Defence re: Kemp - DHAAT 05 (28 May 2021) File Number(s) Re: Lieutenant Colonel George Hulse, OAM (Retd) on behalf of Colonel John Kemp AM (Retd) Applicant And: Department of Defence Respondent Tribunal Air Vice-Marshal John Quaife, AM (Retd) Presiding Member Major General Simone Wilkie, AO (Retd) Mr Graham Mowbray Hearing Date 24 February 2021 DECISION On 28 May 2021, having reviewed the decision by the Chief of Army of 26 February 2020 to not support the award of the Distinguished Service Cross to Colonel John Kemp AM (Retd) for his service in Vietnam, the Tribunal decided to recommend to the Minister for Defence that the decision by the Chief of Army be set aside and that Colonel Kemp be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his command and leadership of 1st Field Squadron Group, Vietnam, between 1 November 1967 and 12 November 1968. CATCHWORDS DEFENCE HONOUR – Distinguished Service Decorations – Distinguished Service Cross – eligibility criteria – 1st Field Squadron Group – Fire Support Base Coral - South Vietnam – MID nomination. LEGISLATION Defence Act 1903 – Part VIIIC - Sections 110T, 110V(1), 110VB(1), 110VB(6). Defence Regulation 2016, Section 35. Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No S25 – Distinguished Service Decorations Regulations – dated 4 February 1991. Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No S18 – Amendment of the Distinguished Service Decorations Regulations – dated 22 February 2012. REASONS FOR DECISION Introduction 1. The applicant, Lieutenant Colonel George Hulse OAM (Retd) seeks review of a decision by the Chief of Army, Lieutenant General Rick Burr AO DSC MVO, of 26 February 2020, to not recommend the award of the Distinguished Service Cross to Colonel John Howard Kemp for his service in Vietnam. -

A Modern Day Anzac Summer Edition 2017

SUMMER EDITION 2017 REMEMBRANCE DAY 2016 ~ WREATH LAYING CEREMONY COUNCILOR DAVID BELCHER ~ WEST WARD ~ LMCC ANDREW MACRAE ~ PRESIDENT ~ WESTLAKE NASHO’S MEMBERS FEES DUE ~ Page 2 NOTICEA MODERN OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING DAY FEBRUARY ANZAC 2017 ~ Page 5 SR-71 ~ BLACKBIRD COMMUNICATION TO TOWER ~ Pages 8 to 10 SOME PHOTOGRAPHS OF OUR XMAS WELFARE CRUISE ~ Page11 THE BATTLE OF BRITAIN ~ 75 YEAR ON ~ Pages 12 to 13 THE TRUE REASON FOR THE RSL SALUTE ~ Page 27 INDIGE- NOUS SERVICE IN AUSTRALIA’S ARMED FORCES IN PEACE & WAR Pages 41 to 48 Official Newsletter of: Toronto RSL sub-Branch PO Box 437 Toronto 2283 [email protected] 02 4959 3699 NNEWCASTLEEWCASTLE ARMOURYARMOURYARMOURY LICENSED FIREARMS DEALER WANTED: EX-MILITARY AND SPORTING FIREARMS PHONE: 0448 032 559 E-MAIL: [email protected] PO BOX 3190 GLENDALE NSW 2285 www.newcastlearmoury.com.au THIS SPACE AVAILABLE FOR ADVERTISING In a time of need turn to someone you can trust. Ph. (02) 4973 1513 SO IF ANYONE OUT THERE WISHES TO PLACE A QUARTER PAGE ADVERTISEMENT IN- SIDE THE FRONT COVER WHICH IS DISTRIBUTED TO OUR MEMBERS AND Pre Arranged Funeral Plan in THE COMMUNITY AS A Association with WHOLE (APPROXIMATELY 1500 COPIES QUARTERLY) barbarakingfunerals.com.au From the president’s Hi all, Here we are another year gone and before you know it it will be Christmas 2017. We have had quite a busy year attending to the various as- pects of the sub-Branch which keeps the motor running. I have a great crew behind me in the running of this office from the Executive, Trustees, Pension and Welfare Offi- cers, the Committee and all others who do not have any specific duty but get in and help when it is needed. -

RAA Liaison Letter Spring 2015

The Royal Australian Artillery LIAISON LETTER Spring 2015 The Official Journal of the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery Incorporating the Australian Gunner Magazine First Published in 1948 RAA Liaison Letter 2015 - Spring Edition CONTENTS Editor’s Comment 1 Letters to the Editor 5 Regimental 9 Professional Papers 21 Around the Regiment 59 RAA Rest 67 Capability 81 LIAISON Personnel & Training 93 Associations & Organisations 95 LETTER Spring Edition NEXT EDITION CONTRIBUTION DEADLINE Contributions for the Liaison Letter 2016 – Autumn 2015 Edition should be forwarded to the Editor by no later than Friday 12th February 2016. LIAISON LETTER ON-LINE Incorporating the The Liaison Letter is on the Regimental DRN web-site – Australian Gunner Magazine http://intranet.defence.gov.au/armyweb/Sites/RRAA/. Content managers are requested to add this to their links. Publication Information Front Cover: An Australian M777A2 from 8th/12th Regiment, RAA at Bradshaw Field Training Area, Northern Territory during Exercise Talisman Sabre 2015. The Talisman Sabre series of exercises is the principle Australian and US military training activity focused on the planning and conduct of mid-intensity ‘High End’ warfighting. Front Cover Theme by: Major D.T. (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Compiled and Edited by: Major D.T. (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Published by: Lieutenant Colonel Dave Edwards, Deputy Head of Regiment Desktop Publishing: Michelle Ray, Army Knowledge Group, Puckapunyal, Victoria 3662 Front Cover & Graphic Design: Felicity Smith, Army Knowledge Group, Puckapunyal, Victoria 3662 Printed by: Defence Publishing Service – Victoria Distribution: For issues relating to content or distribution contact the Editor on email: [email protected] or [email protected] Contributors are urged to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in their articles. -

Evaluating Australian Army Program Performance 106

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Libraries Faculty and Staff Scholarship and Purdue Libraries and School of Information Research Studies 4-14-2020 Australian National Audit Office:v E aluating Australian Army Program Performance Bert Chapman Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_fsdocs Part of the Accounting Commons, Accounting Law Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, Government Contracts Commons, Information Literacy Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Military and Veterans Studies Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, National Security Law Commons, Other International and Area Studies Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, Policy History, Theory, and Methods Commons, Political Economy Commons, Political Science Commons, Public Administration Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Bert Chapman. "Australian National Audit Office:v E aluating Australian Army Program Performance." Security Challenges, 16 (2)(2020): 106-118. Note: the file below contains the entire journal issue. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Security Challenges Vol. 16 No. 2 2020 Special Issue Plan B for Australian Defence Graeme Dobell John Blaxland Cam Hawker Rita Parker Stephen Bartos Rebecca Strating Mark Armstrong Martin White Bert Chapman Security Challenges Vol. 16 / No. 2 / 2020 Security -

Sticking to Our Guns a Troubled Past Produces a Superb Weapon

Sticking to our guns A troubled past produces a superb weapon Chris Masters Sticking to our guns A troubled past produces a superb weapon Chris Masters About ASPI ASPI’s aim is to promote Australia’s security by contributing fresh ideas to strategic decision-making, and by helping to inform public discussion of strategic and defence issues. ASPI was established, and is partially funded, by the Australian Government as an independent, non-partisan policy institute. It is incorporated as a company, and is governed by a Council with broad membership. ASPI’s core values are collegiality, originality & innovation, quality & excellence and independence. ASPI’s publications—including this study—are not intended in any way to express or reflect the views of the Australian Government. The opinions and recommendations in this study are published by ASPI to promote public debate and understanding of strategic and defence issues. They reflect the personal views of the author(s) and should not be seen as representing the formal position of ASPI on any particular issue. Important disclaimer This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in relation to the subject matter covered. It is provided with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering any form of professional or other advice or services. No person should rely on the contents of this publication without first obtaining advice from a qualified professional. © The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Limited 2019 This publication is subject to copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. -

A Proposed New Military Justice Regime for the Australian Defence Force During Peacetime and in Time of War

A PROPOSED NEW MILITARY JUSTICE REGIME FOR THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE DURING PEACETIME AND IN TIME OF WAR Dr David H Denton, RFD QC BA, LLB, LLM (Monash), PhD (UWA) Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Law 2019 THESIS DECLARATION I, DAVID HOPE DENTON, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text and, where relevant, in the Authorship Declaration that follows. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis contains only sole-authored work, some of which has been published and/or prepared for publication under sole authorship. Signature: Date: 16 September 2019 © The author iii ABSTRACT Only infrequently since Federation has the High Court of Australia been called upon to examine the constitutionality of the Australian military justice system and consider whether the apparent exercise of the defence power under s51(vi) of the Constitution to establish service tribunals may transgress the exercise of the judicial power of the Commonwealth under Chapter III of the Constitution. -

Newsletter Telephone: (02) 9393 2325 Issue No

Locked Bag 18, Royal United Services Institute Darlinghurst NSW 2010 New South Wales Level 20, 270 Pit Street 1 SYDNEY NSW 2000 www.rusinsw.org.au [email protected] Newsletter Telephone: (02) 9393 2325 Issue No. 14 - SEPTEMBER 2015 Fax: (02) 9393 3543 Introduction Welcome to this month’s issue of the electronic newsletter of the Royal United Services Institute of NSW (RUSI NSW), the aim of which is to provide members, stakeholders, and other interested parties up to date news of our latest activities and events as well as selective information on defence issues. Major General J. S. There is no charge to receive this newsletter electronically and recipients are Richardson CB, RUSI NSW Founder not required to be a member of the RUSI of NSW. Invite your colleagues to receive this newsletter by going to the newsletter page on the RUSI NSW website http://www.rusinsw.org.au/Newsletter where they can register their email contact details. Special Event Image Source: Australian War Memorial Of particular interest in this month is the staging of a Commission of Inquiry into the failure of the Allied offensive on Gallipoli in August 1914. Drawing on evidence from both sides which has come to light since the official histories were written, the Commissioner, assisted by Counsel Assisting, will examine witnesses representing the senior officers from the Allied and Turkish sides with a view to eliciting the causes of the failure of the Allied offensive and the lessons of enduring strategic and operational import to emerge there from. To be produced by Major General Paul Irving, AM, PSM, RFD, a Vice President of the Institute, this is one of the special events being conducted by the Institute to commemorate the centenary of World War 1. -

Newsletter [email protected] Issue No

Anzac Memorial, Hyde Park Royal United Services Institute for South, Sydney NSW 2000 1 Defence and Security Studies, NSW Inc PO Box A778 SYDNEY SOUTH NSW 1235 www.rusinsw.org.au Newsletter [email protected] Issue No. 48 – February/March 2019 Telephone: (02) 8262 2922 Introduction Welcome to this month’s issue of the electronic newsletter of the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies NSW, the aim of which is to provide members, stakeholders, and other interested parties up to date news of our latest activities and events, as well as selective information on defence issues. There is no charge to receive this newsletter electronically and recipients are not required to be a member of the Institute. Invite your colleagues to receive this newsletter by going to the newsletter page on the Institute’s website http://www.rusinsw.org.au/Newsletter where they can register their email contact details. Upcoming Institute Lunchtime Lectures and Social Events Tuesday 30 April 2019 Speaker: Brigadier Peter Connor, AM, Former Commander Australia’s Task Group, Afghanistan – Subject: The War in Afghanistan - A Recent Commander’s Experiences Brigadier Connor enlisted in the Australian Army in 1985, being commissioned in 1988 through Sydney University Regiment. He was allocated to the Royal Australian Infantry Corps. He served as a platoon commander with 4th Battalion Royal Green Jackets, a British Army Territorial infantry unit based in London. His further regimental service was through 2nd /17th Battalion, the Royal New South Wales Regiment (2/17 RNSWR) in Sydney. He commanded 2/17 RNSWR from 2005 to 2006. -

DANGER CLOSE: the Battle of Long Tan PRODUCTION NOTES

DANGER CLOSE: The Battle of Long Tan PRODUCTION NOTES PUBLICITY REQUESTS: Amy Burgess / National Publicity Manager, Transmission Films 02 8333 9000, [email protected] Images: High res images and poster available to download via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: https://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/danger-close-the-battle-of-long-tan Running Time: 118 mins Distributed in Australia by Transmission Films DANGER CLOSE: The Battle of Long Tan – Production Notes SHORT SYNOPSIS South Vietnam, late afternoon on August 18, 1966 - for three and a half hours, in the pouring rain, amid the mud and shattered trees of a rubber plantation called Long Tan, a dispersed company of 108 young and mostly inexperienced Australian and New Zealand soldiers are fighting for their lives, holding off an overwhelming force of over 2,000 battle hardened North Vietnamese soldiers. SYNOPSIS Inspired by a true story, DANGER CLOSE begins with Major Harry Smith [Travis Fimmel], the strict and highly motivated commander of Delta Company, 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, on operation in Nui Dat, Phuoc Tuy Province, Vietnam. Delta Company is made up of four platoons; 10, 11 and 12 platoons and a Company HQ, a total of 108 men. Harry is a career officer and he has no time to ‘coddle’ or befriend the men in his company. He feels that ‘babysitting’ these young men - half of which are conscripts - is beneath his special forces skills and previous combat experience. But with a point to prove, Harry is keen to show what his men, and importantly, he can do to make the best of a harrowing situation.