Comparative Study of Utilization of Maternal and Child

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

World Bank Document

SFG1692 V36 Hospitalia Consultaire Ltd ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) Public Disclosure Authorized NNEWICHI GULLY EROSION SITE, NNEWI NORTH LGA, ANAMBRA STATE Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Anambra State Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project Public Disclosure Authorized November 2017 Table of Contents List of Plates ..................................................................................................................... v List of Tables .................................................................................................................. vii list of acronyms ............................................................................................................. viii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... ix 1 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ 17 1.1 Background ..................................................................................................................... 17 1.2 Hydrology ........................................................................................................................ 18 1.3 Hydrography .................................................................................................................... 19 1.4 Hydrogeology .................................................................................................................. 20 1.5 Baseline Information -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

Dictionary of Ò,Nì,Chà Igbo

Dictionary of Ònìchà Igbo 2nd edition of the Igbo dictionary, Kay Williamson, Ethiope Press, 1972. Kay Williamson (†) This version prepared and edited by Roger Blench Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm To whom all correspondence should be addressed. This printout: November 16, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations: ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Editor’s Preface............................................................................................................................................... 1 Editor’s note: The Echeruo (1997) and Igwe (1999) Igbo dictionaries ...................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Earlier lexicographical work on Igbo........................................................................................................ 4 2. The development of the present work ....................................................................................................... 6 3. Onitsha Igbo ................................................................................................................................................ 9 4. Alphabetization and arrangement.......................................................................................................... -

Household Water Demand in the Peri-Urban Communities of Awka, Capital of Anambra State, Nigeria

Vol. 6(6), pp. 237-243, August, 2013 DOI: 10.5897/JGRP2013.0385 Journal of Geography and Regional Planning ISSN 2070-1845 © 2013 Academic Journals http://www.academicjournals.org/JGRP Full Length Research Paper Household water demand in the peri-urban communities of Awka, Capital of Anambra State, Nigeria E. E. Ezenwaji1*, P.O. Phil-Eze2, V. I. Otti3 and B. M. Eduputa4 1Department of Geography and Meteorology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria. 2Department of Geography, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria. 3Civil Engineering Department, Federal Polytechnic, Oko, Nigeria. 4Department of Environmental Management, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria. Accepted 22 July, 2013 The aim of this paper is to determine relevant factors contributing to the water demand in the peri-urban communities of Awka capital city. Towards achieving this aim, questionnaire were developed and served on the households in various communities to collect relevant data on the 13 physical and socio- economic factors we earlier identified as influencing water demand in the area. Water quality was ascertained through microbiological analysis of water samples. The major analytical techniques used were multiple correlations, the result of which was subjected to Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Principal Component Regression. Result shows that the 13 variables combined to contribute 90.0% of water demand in the area. Furthermore, the low standard error of estimates of 0.029 litres shows that water demand in the communities could be predicted using the 13 variables. Policy and planning measures to improve the water supply situation of the area were suggested. Key words: Capital, communities, factors, peri-urban, water demand. -

STRUCTURE PLAN for Awka and SATELLITE TOWNS

AWKA STRUCTURE PLAN FOR AWKA AND SATELLITE TOWNS Anambra State STRUCTURE PLAN FOR AWKA AND SATELLITE TOWNS Anambra State 1 Structure Plan for Awka and Satellite Towns Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), 2009 All rights reserved United Nations Human Settlements Programme publications can be obtained from UN-HABITAT Regional and Information Offices or directly from: P.O.Box 30030, GPO 00100 Nairobi, Kenya. Fax: + (254 20) 762 4266/7 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.unhabitat.org HS/1152/09E ISBN: 978-92-1-132118-0 DISCLAIMER The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), the Governing Council of UN-HABITAT or its Member States. Excerpts from this publication may be reproduced without authorisation, on condition that the source is indicated. Photo Credits : © UN-HABITAT acknowLEDGEMents Director: Dr Alioune Badiane Principal Editor: Prof. Johnson Bade Falade Co-ordinator: Dr. Don Okpala Principal Authors: Prof. Louis C. Umeh Prof. Samson O. Fadare Dr. Carol Arinze –Umobi Chris Ikenna Udeaja Tpl. (Dr) Francis Onweluzo Design and Layout: Andrew Ondoo 2 FOREWORD t is now widely It is to reverse and stem this development trend acknowledged and to realize the developmental potentials of well- and accepted that planned and managed cities, towns and villages, that citiesI and urban areas my Government approached the United Nations are engines of economic Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) in development and growth. -

List of Coded Health Facilities in Anambra State.Pdf

Anambra State Health Facility Listing LGA WARD NAME OF HEALTH FACILITY FACILITY TYPE OWERSHIP CODE (PUBLIC/ PRIVATE) LGA STATE OWERSHIP FACILITYTYPE FACILITYNUMBER Primary Health Centre Oraeri Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0001 Primary Health Centre Akpo Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0002 Ebele Achina PHC Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0003 Primary Health Centre Aguata Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0004 Primary Health Centre Ozala Isuofia Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0005 Primary Health Centre Uga Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0006 Primary Health Centre Mkpologwu Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0007 Primary Health Centre Ikenga Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0008 Health Centre Ekwusigo Isuofia Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0009 Primary Health Centre Amihie Umuchu Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0010 Obimkpa Achina Health Centre Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0011 Primary Health Centre Amesi Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0012 Primary Health Centre Ezinifite Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0013 Primary Health Centre Ifite Igboukwu Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0014 Health Post Amesi Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0015 Isiaku Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0016 Analasi Uga Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0017 Ugwuakwu Umuchu Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0018 Aguluezechukwu Health Post Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0019 Health Centre Umuona Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0020 Health Post Akpo Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0021 Health Center, Awa Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0022 General Hospital Ekwuluobia Secondary Public 04 01 1 1 0023 General Hospital Umuchu Secondary Public 04 01 2 1 0024 Comprehensive Health Centre Achina Primary Public 04 01 1 1 0025 Catholic Visitation Hospital, Umuchu Secondary Private 04 01 2 2 0026 Continental Hospital Ekwulobia Primary Private 04 01 1 2 0027 Niger Hospital Igboukwu Primary Private 04 01 1 2 0028 Dr. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

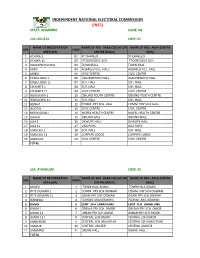

State: Anambra Code: 04

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ANAMBRA CODE: 04 LGA :AGUATA CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ACHINA 1 01 ST CHARLED ST CHARLED 2 ACHINA 11 02 PTOGRESSIVE SCH. PTOGRESSIVE SCH. 3 AGULEZECHUKWU 03 TOWN HALL TOWN HALL 4 AKPO 04 AGBAELU VILL. HALL AGBAELU VILL. HALL 5 AMESI 05 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 6 EKWULOBIA 1 06 UMUEZENOFO HALL. UMUEZENOFO HALL. 7 EKWULOBIA 11 07 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 8 EZENIFITE 1 08 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 9 EZENIFITE 11 09 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 10 IGBOUKWU 1 10 OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE 11 IGBOUKWU 11 11 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 12 IKENGA 12 COMM. PRY SCH. HALL COMM. PRY SCH. HALL 13 ISUOFIA 13 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 14 NKPOLOGWU 14 MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE 15 ORAERI 15 OBIUNO HALL OBIUNO HALL 16 UGA 1 16 OKWUTE HALL OKWUTE HALL 17 UGA 11 17 UGA BOYS UGA BOYS 18 UMUCHU 1 18 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 19 UMUCHU 11 19 CORPERS LODGE CORPERS LODGE 20 UMOUNA 20 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE TOTAL LGA: AYAMELUM CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ANAKU 1 TOWN HALL ANAKU TOWN HALL ANAKU 2 IFITE OGWARI 1 2 COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI 3 IFITE OGWARI 11 3 OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI 4 IGBAKWU 4 ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU 5 OMASI 5 CENT. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 22, 2017 # Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 Abatete Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abatete Town, Idemili Local Govt Area, Anambra State ANAMBRA 4 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 5 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 6 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 7 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 8 Abokie Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Plot 2, Murtala Mohammed Square, By Independence Way, Kaduna State. KADUNA 9 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi Bauchi 10 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 11 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 12 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 13 Acheajebwa Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Sarkin Pawa Town, Muya L.G.A Niger State NIGER 14 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 15 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 16 Acuity Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 167, Adeniji Adele Road, Lagos LAGOS 17 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. -

Estimation of Aquifer Parameters in Awka and Environs, Anambra State, Nigeria, Using Electrical Resistivity Method

International Journal of Innovative Scientific & Engineering Technologies Research 8(4):1-29, Oct.-Dec., 2020 © SEAHI PUBLICATIONS, 2020 www.seahipaj.org ISSN: 2360-896X Estimation of Aquifer Parameters in Awka and Environs, Anambra State, Nigeria, using Electrical Resistivity Method Onyenweife, G.I1*., Nwozor, K.K1., Onuba, L.N1., Nwike, I.S1 & Egbunike, M.E1. Department of Geology, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Uli, Nigeria *Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The indiscriminate drilling and increasing populace and their economic activities have been in collaboration to abstraction of groundwater potential in the study area. Apparently, the above mentioned challenges of Awka and environs have proven the basis to unleash the aquiferous zones and parameters from the analysis of groundwater system for proper knowledge of aquifers in the study area. The use of electrical resistivity method which is the most commonly used geophysical method of groundwater exploration were employed in this study. In this electrical resistivity method, the use of Schlumberger array posed greater importance in delineating the aquifer parameters described by depth, thickness, transmissivity and hydraulic conductivity. Aquifer is described as geological formation capable of yielding economic quantity of water through recharge and discharge via water cycle. VES data of the nine (9) communities of Awka and environs at two locations each were plotted with IPI2WIN software and interpreted geologically and geophysically in subsections, the results revealed 4-6 layers. The nine (9) communities of Awka and environs were subdivided into zone A and zone B to enable easy work flow and pumping test analysis using the two existing borehole VES 4 and VES 14 data. -

Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project Health and Environment

Hostalia ConsultaireE2924 NigerianNigerian Erosion Erosion and Watershed Managementand Watershed Project Management Health and EnvironmentProject NEWMAP Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Public Disclosure Authorized Framework (ESMF) FINAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Hostalia Consultaire Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project Health and Environment ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project NEWMAP FINAL REPORT SEPTEMBER 2011 Prepared by Dr. O. A. Anyadiegwu Dr. V. C. Nwachukwu Engr. O. O. Agbelusi Miss C.I . Ikeaka 2 Hostalia Consultaire Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project Health and Environment Table of Content Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..............................................................................15 Background ..........................................................................................................................15 TRANSLATION IN IBO LANGUAGE..........................................................22 TRANSLATION IN EDO LANGUAGE.........................................................28 TRANSLATION IN EFIK...............................................................................35 CHAPTER ONE..............................................................................................43 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND TO NEWMAP.............................43 1.0 Background to the NEWMAP...................................................................................43